Q&A: The High Wall: BRANDON THO HARRIS

By Jesse Egner and Kelly Lee Webeck | August 18, 2022

Brandon Tho Harris is an interdisciplinary artist and arts professional based in Houston, Texas. His creative practice explores his identity as a child of war refugees. Through intensive research on the Vietnamese diaspora in relation to his family history, he examines notions of intergenerational trauma, displacement, and the land as a living archive. Found in his work are often self-portraiture, his family archives, found objects, raw materials, and historical images portraying the Vietnam war. By the use of photography, video, performance, and installation, he provides viewers with a deeper understanding of the complexities surrounding migration.

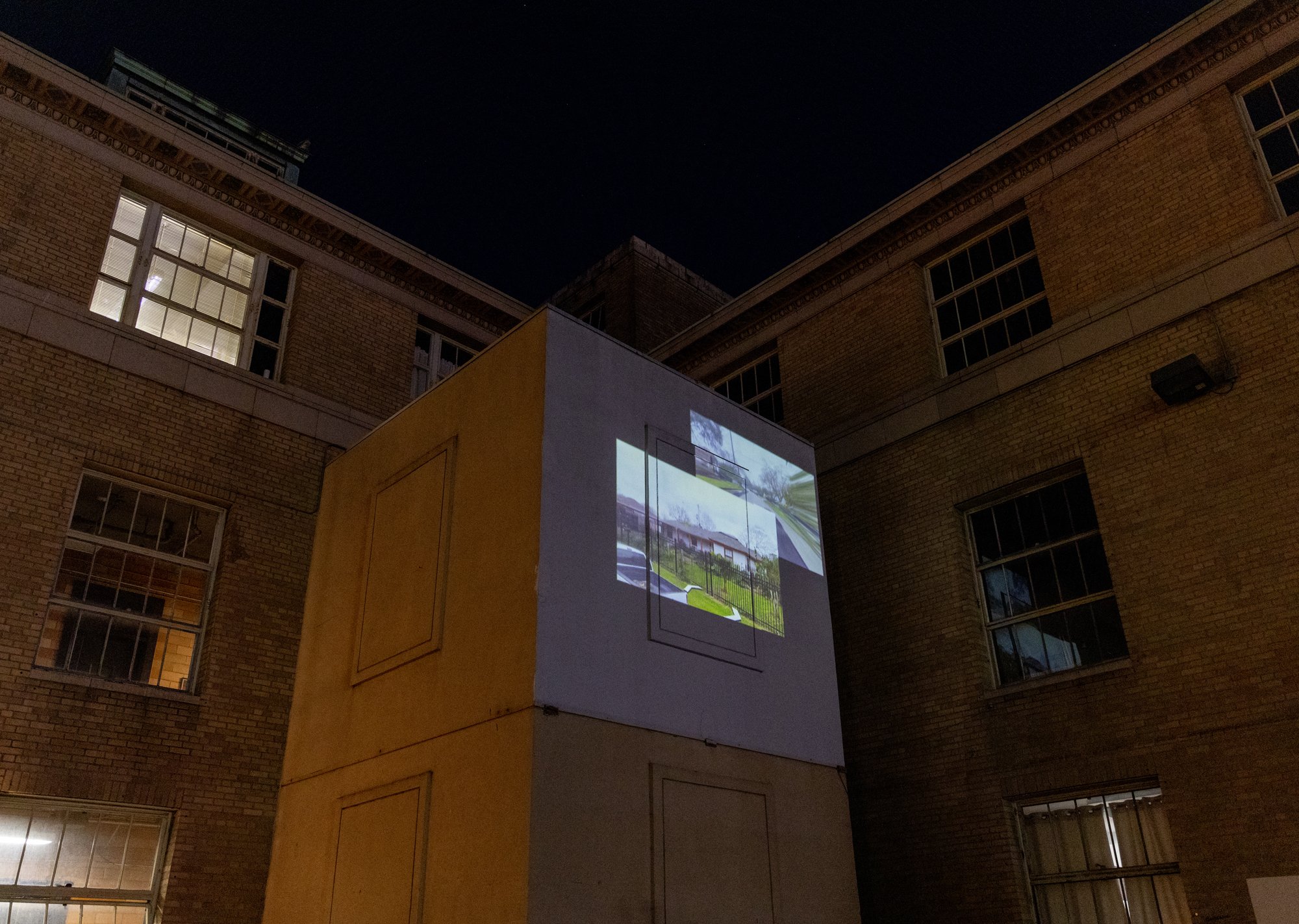

The High Wall 2022—in partnership with Strange Fire Collective— presents three video works to be projected on the facade of the Inscape Arts Building in Seattle, WA. Inscape resides in a former immigration detention center; because of the building’s history we have selected artists whose work explore broad ideas of immigration, diaspora, and borderlands. We are proud to have chosen Kei Ito, Brandon Tho Harris, and Julie Lee - three artists who examine these themes through the use of photography and the moving image. Although each piece is presented as a video, the artists each utilize the medium and materiality of still photography. Photograms, a vernacular family photo archive, and glitched google map images each make connections about migration, place, community, family, and home.

Spaces of Home, 2020

Kelly Lee Webeck + Jesse Egner: Hello Brandon! We are both so happy to welcome you to Strange Fire Collective and thrilled that we were able to include your work in The High Wall: 2022 exhibition. Why do you feel that the Inscape Building, where The High Wall exhibition is being shown, is a good location to show your work?

Brandon Tho Harris: Hello Kelly and Jesse! Thank you very much for including me on Strange Fire. I am such a huge fan of the amazing work you all are doing!

The location of The High Wall exhibition is quite a peculiar site for an art space. After doing some research on the history of The Inscape Building and learning that it was the site of over 70 years of deportation dating back to 1932, I could only think of the thousands of people that have been held there before getting deported. Each with their own unique story, hopes for the future, memories of a previous home, and all longing for a new one. The work included in this exhibition expands on the concept of constantly searching for a home and the liminal space of migration.

KW + JE: Can you tell us about how “Spaces of Home” came to be? You utilize Google Earth to explore specific sites. Can you tell us about where you visited in this digital landscape?

BTH: Spaces of Home is the culmination of my desire to visualize my family homes before and after fleeing the country during the Vietnam War. As a child, and into adulthood, I always wondered what became of the house that my family left to come to America. My family comes from a small village in the middle of Vietnam, and I cannot help but think about what has happened to it. Is it destroyed? Is it a skyscraper? Who lives here now, if anybody?

My curiosity led me to try to find these answers on Google Earth. My grandmother could only tell me the village's name and a generalized area near the middle of Vietnam. I was searching and searching for some remnants of a home in the area, or re-imagining what I found as if it was my family’s home. In the end, the technology of Google Street View does not have any data on this underdeveloped region. They depicted it as a flat infinite landscape, which I interpret as an immigrant/refugee space. Unable to see what is in front of you, searching for home, wherever that may be. I visited my family homes throughout Houston in East Downtown (the original Asiatown of Houston) and in Humble, where they lived surrounded by other Vietnamese refugees on the same street. In the video work, the Houston homes are visualized as if you are traveling through the street, yet every time you move in any direction, it becomes an abstract version of that place. These spaces look familiar with the houses and freshly cut grass, trashcan-lined streets, and the grids that make a city, yet, navigating through it all, it transforms into this space that is unrecognizable. I see this as a visualization of the mental states that migration can cause.

KW + JE: Where is home for you and what does “home” mean? Have you been to Vietnam?

BTH: This is a very interesting question. As a child of Vietnamese refugees, I long for a home that is unfamiliar to me, which is Vietnam. But because I have grown up and lived my entire life in Texas, I see that as my home as well. I live in the in-between state of being too American for Vietnam and too Vietnamese for America. It is something that I am still trying to figure out myself. The only time I visited Vietnam was with my father in 2016. This trip was more of a tourist experience, and I wish I was creating the work and research I am doing now back then.

Spaces of Home, film still, 2020

KW + JE: Other bodies of work in your portfolio incorporate your own family archive as well as appropriated images from LIFE magazine. How does appropriating images from different sources fit into your artistic practice?

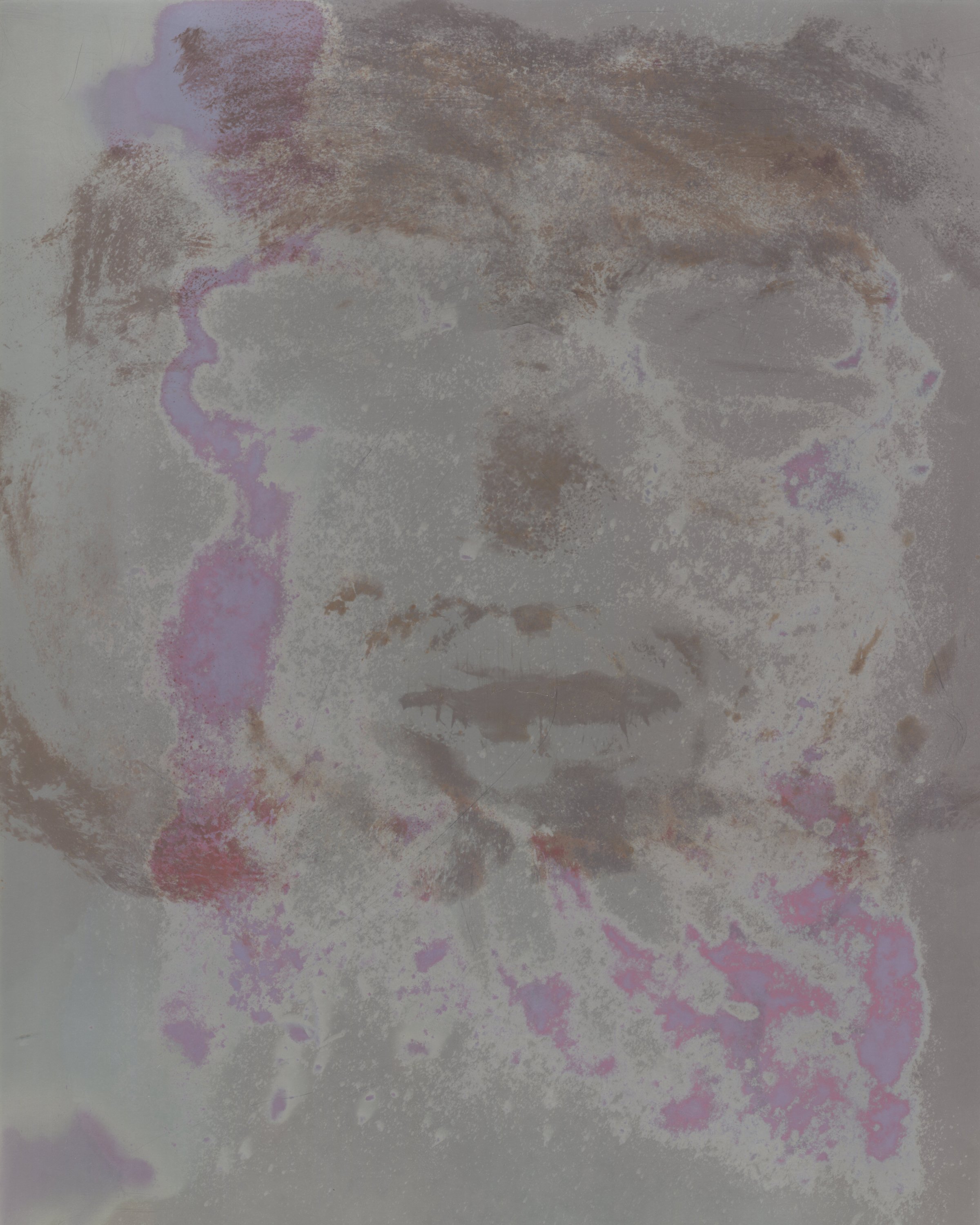

BTH: When my family was escaping Vietnam during the war, they buried most of their photographs and identification documents to erase their identities. I believe this is the root of why I often incorporate archival images of my family that survived the war. Because of the lack of photographs of my family from before and during the war, I desired to better understand my family’s history, which was never discussed growing up.

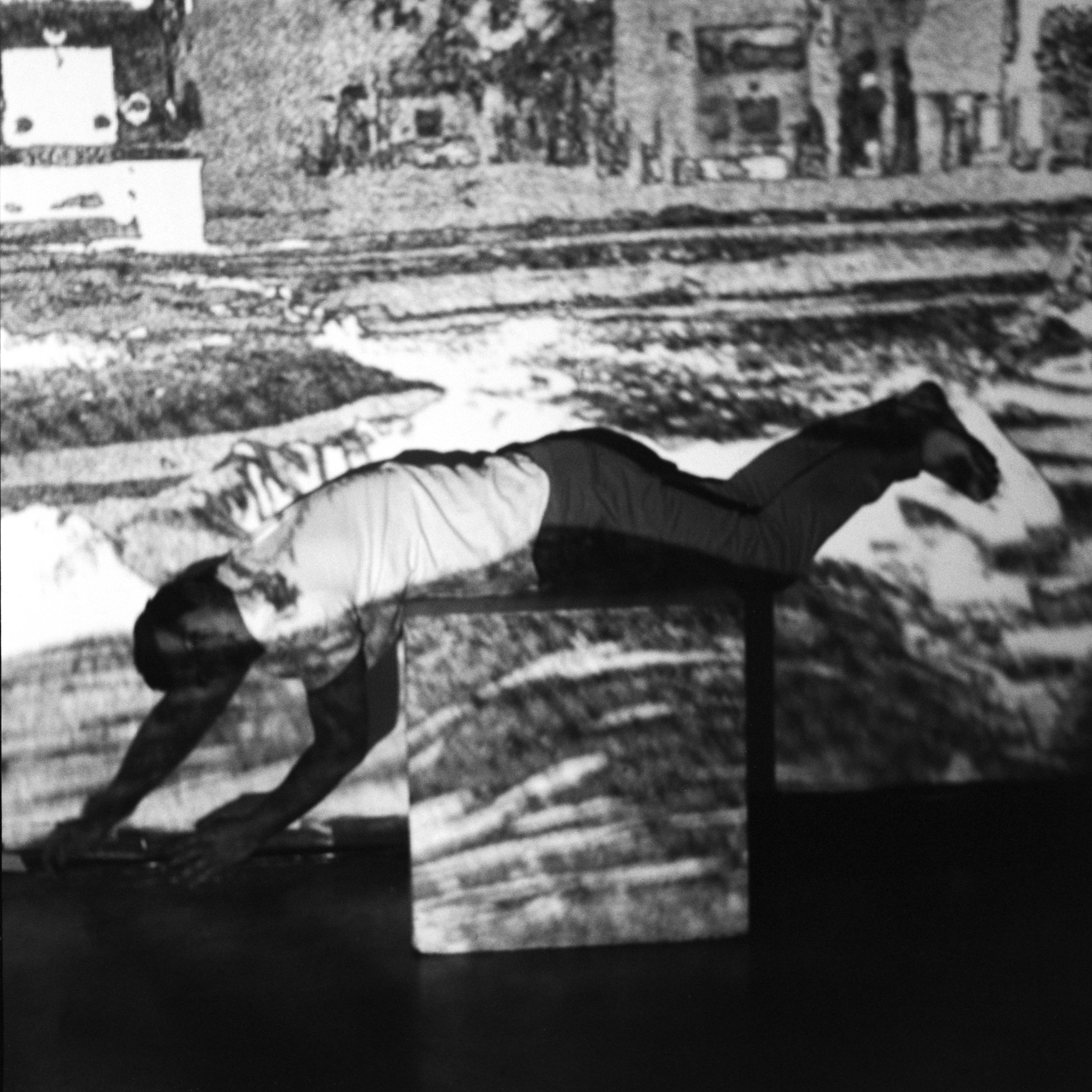

The Vietnam War was the first war to be fully documented 24/7 through images and videos that were then dispersed and circulated globally. On one trip to a local antique store, I came across a collection of old LIFE Magazines and purchased them. Once I started to dive into the magazines, I came to notice that they often portrayed the Vietnamese refugees as helpless and the American soldiers as their saviors. They would have photographs of the deceased or injured juxtaposed with advertisements for a refreshing Coca-Cola. In my opinion, it seems like the photographers were seeking images that would evoke shock in their viewers. It lacked empathy for the people in the images that were just trying to survive. Many years after the war, these photographs have become “iconic images” depicting the effects of war, but I couldn’t help but think that the people in these images could have been my family members. Images are powerful and it is important to be aware of the role that images play in society. I appropriate these images in my practice to take back ownership of the photos by using my own body or by abstracting them through traditional photography methods.

Spaces of Home, film still, 2020

KW + JE: Going off the idea of working with archives, can you tell us more about what was it like working with the Google Earth archive? This is a huge archive of images tied to very specific places. It's incredibly powerful in the ways that you can manipulate it and you can move through it like it is a physical space but in the end it is just an archive of images. What was that like?

BTH: Google has dominated and collected a vast amount of visual culture since the dawn of the internet. The Google Earth platform is comprised of millions of images stitched together attempting to re-create our realities. I remember when I was younger, I often would go onto the program to look at famous landmarks and places that I wished to visit. Now as an adult, I reflect on how we are constantly being monitored and under surveillance. The images become the property of Google, constantly documenting the subtle changes and nuances of a location. I am interested in the ways in which technology creates this digital realm through an archive of millions of photographs to reconstruct something that feels familiar to us. By navigating this digital space, I aim to challenge the medium of photography, which is regarded as the truest to our reality, yet the technology of image production is not perfect and never will be.

KW + JE: Is all the glitch, and distortion and abstraction that is present in the video coming directly from Google Earth or are you manipulating the images as well?

BTH: All of the abstractions were created by Google Earth. While using the program, I was drawn to the glitching and distortions that occurred when traveling from one location to another. This only happened in the space of transition on that platform. After realizing this fault in their software, I began to view this abstraction as the space of migration. It was the space in-between here and there, a transitional space that visualizes the notion of movement and displacement.

Spaces of Home, film still, 2020

KW + JE: Can you tell us more about the layering and why you chose to layer certain scenes and moments together?

BTH: In Spaces of Home, I use layering to convey many different meanings throughout the piece. Towards the beginning of the video, I layer two clips from the same location that rotate and mimic a compass seeking direction. I also use layering to connect different locations to one another and/or reconstruct the image. The images are like memories, and I am trying to fill in the gaps. In the last scene, the background of the site is the area where my family’s village would have been located. I layer it together with the location of their first attempt to make a “home” in the United States. The layers throughout the video function like a memory of a place, bits and pieces and the process of remembering is weaving each piece together to re-construct the moment.

KW + JE: In the context of The High Wall, the video is shown without audio. The original piece, however, does contain audio. Can you shine some light on your decision making process to choose the audio? As well, tell us what the piece means to you without any audio.

BTH: The original video has three audio clips from my mother and grandmother. Two were selected from an interview that I did with my mother, in which shedescribes a memory of home in Vietnam, reminiscing about going with her father down to the river to catch crawfish. The other was her describing how she longed for the family photographs that were lost at war. The last audio was a voicemail my grandmother left for me. In the background, I created a soundscape of water to reference the Vietnamese refugee’s ties to water. The word for water in Vietnamese, nước, has a dual meaning and can also be used as homeland or country. I view water as a transitional space that provides the refugees with hope and dreams of the future, but also as a site of loss and pain.

Without the audio, the piece becomes more universal and open for the viewers to interpret. The audio enforces the intimate nature of memory and my family’s relationship to these sites. The version without audio allows the viewer to put themselves in my role of navigating through space and time.

Spaces of Home, film still, 2020

KW + JE: Throughout the video you guide us viewers through Google Earth and to a number of different locations. Do you consider this piece to be a performance?

BTH: That is an interesting observation! While creating it I did not view it as a performance piece. Thinking of the video now, I can see how it could be a virtual performance where I take the viewer through space to different areas that my family once lived in. It becomes a sort of performance in the digital age or in memory.

KW + JE: You work a fulltime job at FotoFest in Houston, Texas as well as maintain an impressive professional studio practice where you show your work, apply to exhibitions and grants and so much more. How do you create balance in your life?

BTH: To be honest it is extremely difficult to balance an artistic practice and to work in the arts. I am still trying to figure out how to make time for myself in the studio. It is a constant cycle of giving and taking. Ultimately my practice is just as important to me as the work I do through FotoFest and I am making it work.

KW + JE: Your work is closely tied to your family story and you use images from your family’s archive. How has your family received your work?

BTH: My family is my biggest support and inspiration. Much of this familial history has been repressed for so long. My practice has created space for storytelling and intergenerational healing. They are my collaborators and are part of the process the entire time and through this, there is a peace that comes after confronting this painful past. My family typically likes to be behind the scenes of my practice, but just this past year, I persuaded my grandmother and mother to be in performance with me and it was the most beautiful experience ever. I view my work as a catalyst to share their story with others because being a refugee is not a choice; It is the act of survival.

Spaces of Home, film still, 2020

KW + JE: What’s next for you? Do you have any exhibitions coming up?

BTH: I am currently in a transitional state in my life. I received my Bachelor of Fine Arts in the concentration of photography and digital media two years ago and plan on going to graduate school in the future, but I have also been moving away from image-making and exploring more sculptural work. I would love to participate in more artist residencies and spend more time in the studio and building community.

I am participating in a few exhibitions coming up this fall in Houston! My sculpture Mẹ Việt Nam ơi, Chúng Con Vẫn Còn đây (Oh Mother Vietnam, We Are Still Here) will be exhibited at Houston Center for Contemporary Craft as a part of CraftTexas 2022, and then will move to the Houston Public Library to be presented in the Julia Ideson Building for an exhibition organized by Rice University’s Houston Asian American Archive. I will also be in the exhibition Lo que me queda de tu amor (What’s left of your love for me) at Lawndale Art Center. In this exhibition, curators Francis Almendárez and Mary Montenegro examine the ways in which one carries and passes on different histories through performance, sound, and objects. Additionally, I will be in an outdoor sculpture exhibition at The Orange Show titled Grounded organized by artists Ceci Norman and Matt Manalo. This fall is pretty booked up, but I am so happy to be working with so many talented local artists here in Houston.

KW+JE: Thank you again for taking this time to speak with us. It has been a pleasure learning more about your work, and we’re so honored to include your piece in the High Wall 2022 exhibition!

Bà ngoại, Ông ngoại (Grandmother, Grandfather), Archival Inkjet Photograph, 2020

Mẹ Việt Nam ơi, Chúng Con Vẫn Còn đây (Oh Mother Vietnam, We are Still Here), Reclaimed wood and dirt from sites of Vietnamese movement and migration in the Gulf coast, weavings of Vietnamese flags, rope, fiberglass from a capsized Vietnamese shrimper boat, family artifacts and clothing, 2020

Projection #1, from the series My Life Magazine, Silver Gelatin Photograph, 2019

Projection #2, from the series My Life Magazine, Silver Gelatin Photograph, 2019

Projection #3, from the series My Life Magazine, Silver Gelatin Photograph, 2019

Shock, Pain and Hysterical Wonder, from the series My Life Magazine, Silver Gelatin Photograph, 2019

Visions of Tomorrow, installation view, 2021

Nail Art, Archival inkjet print, gold leaf, rhinestones, 2020

My Body is Your Landscape, Lumin Print, 2020

Ashes, Ashes, Silver Gelatin Photograph, 2021

The Sea Calls to Me, Silver Gelatin Photograph, 2021

H-TOWN TILL I DROWN, Joss paper car, paper clay, silver paint, vinyl “SCREWSTON” decal, 2022

Kim Hung Market, Archival inkjet photograph, 2022

Ruins of Our Memories, Archival inkjet photograph, 2022

All images © Brandon Tho Harris