Feature: Robert E. jackson

By Rafael Soldi | Published July 13, 2017

Robert E. Jackson has collected snapshots since 1997. In the fall of 2007, his collection was the subject of a show and catalogue entitled “The Art of the American Snapshot: 1888-1978” which was on view at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. In early 2008, the show traveled to the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. A second book featuring his collection was entitled “Pure Photography”. It was published in late 2011 by Ampersand Gallery & Fine Books in Portland, Oregon and included sixty images chosen by Jackson to embody the non-narrative aspect of snapshot photography. There was also an accompanying exhibition at Ampersand. In addition, over twenty of his photos were included in the 2011 bestselling young adult book “Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children” by Ransom Riggs. In October of 2012, Seattle-based Marquand Books published photos from Jackson’s color snapshot collection in the book “The Seduction of Color”. The Los Angeles based gallery Ambach & Rice featured his collection in their December 2012 show “Lost & Found: Anonymous Photography in Reflection”. Approximately fifty snapshots from Jackson’s collection were paired with such photographers as Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Walker Evans and Catherine Opie. In June of 2013, Pace/MacGill Gallery in New York City featured his collection in a show entitled “Snap Noir: Snapshot Stories”. Jackson holds a MA degree in art history from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and a MBA from the University of Texas, Austin.

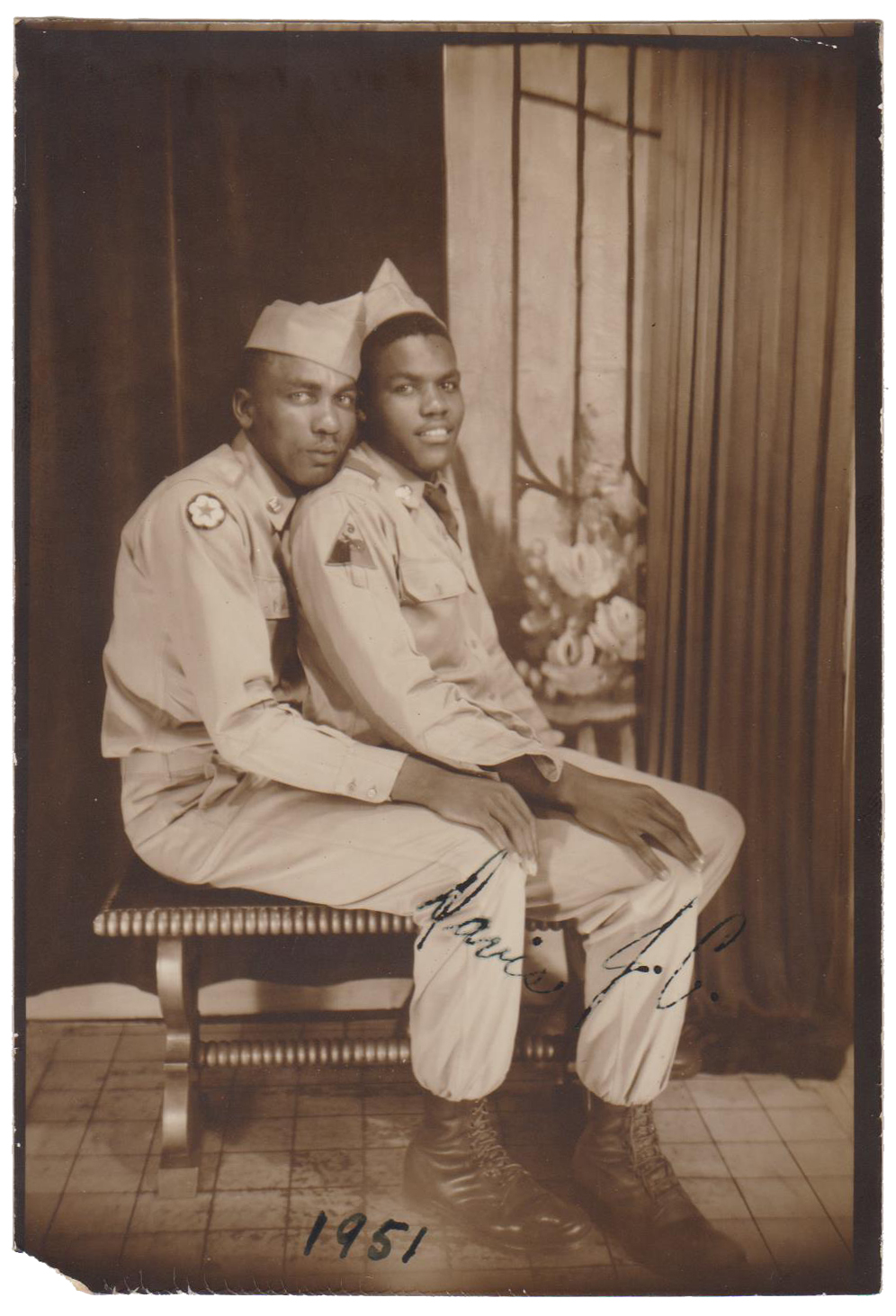

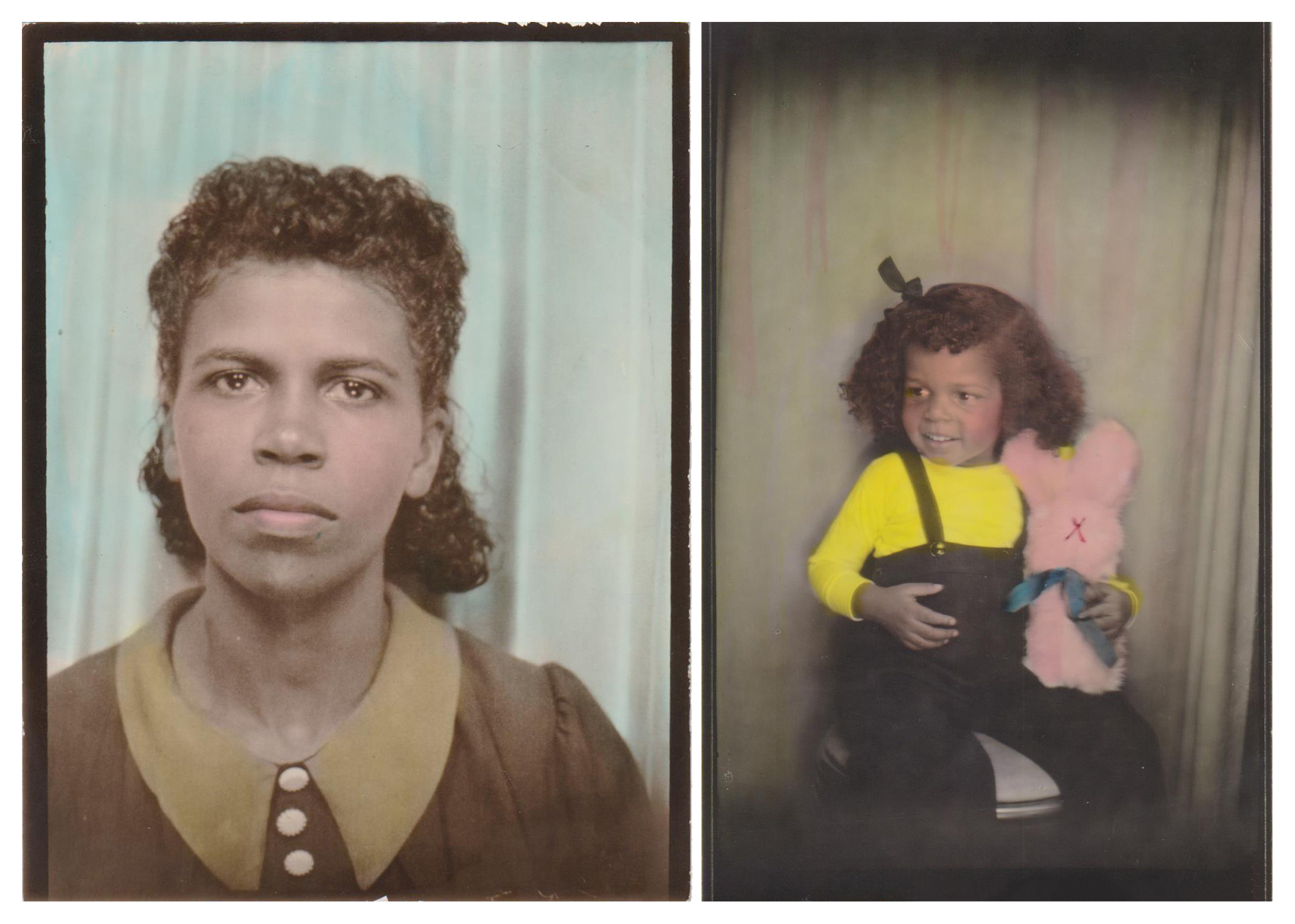

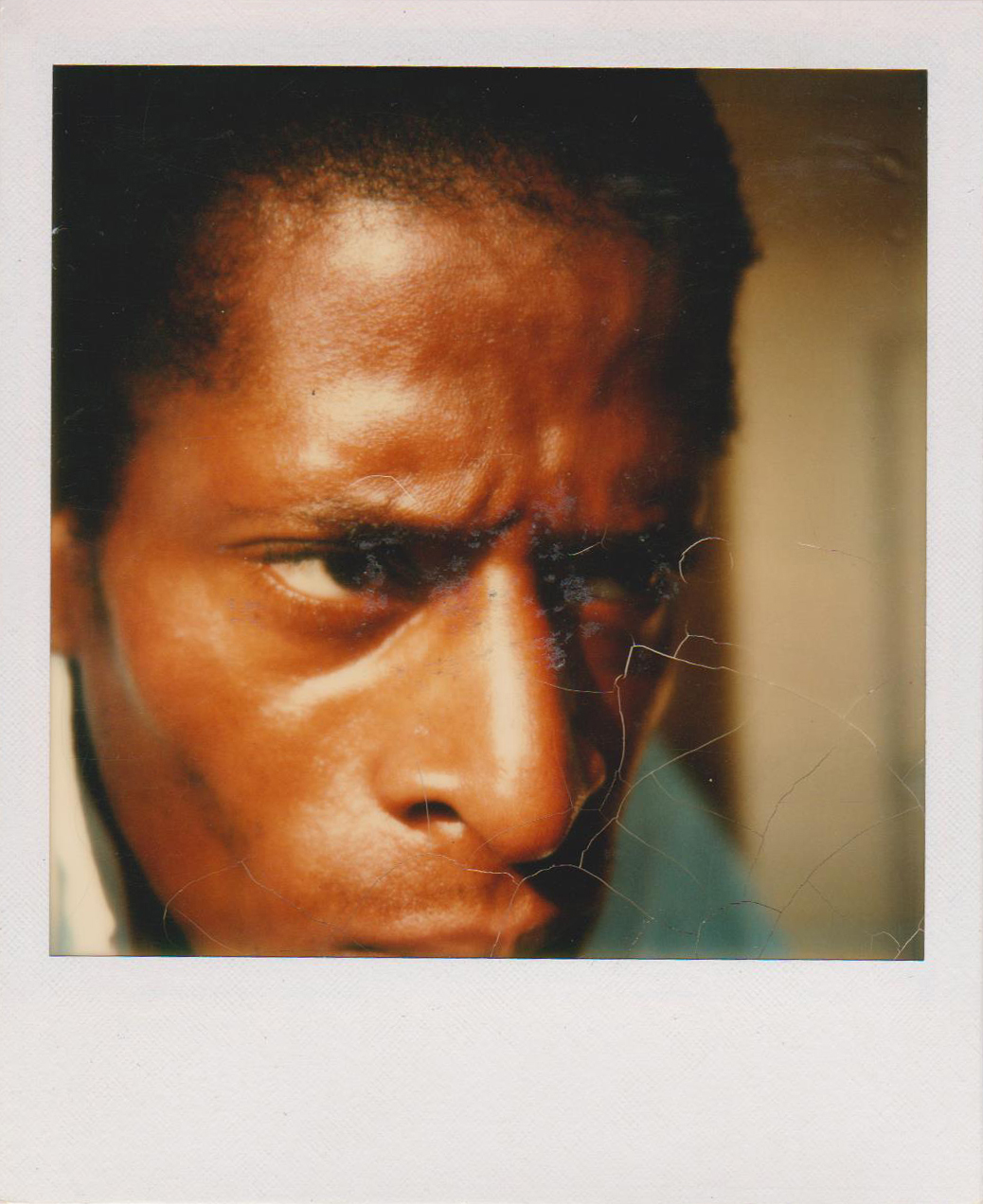

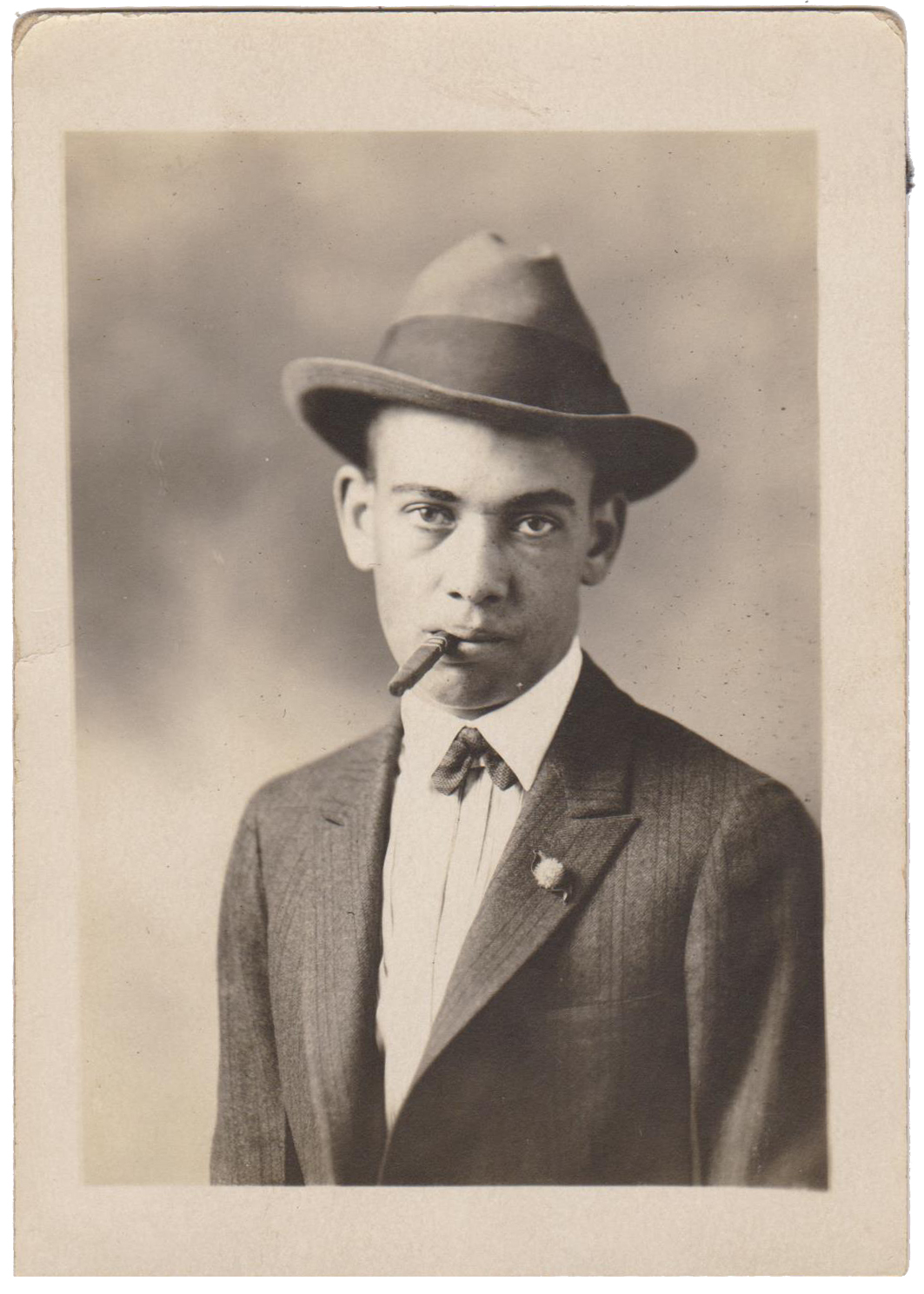

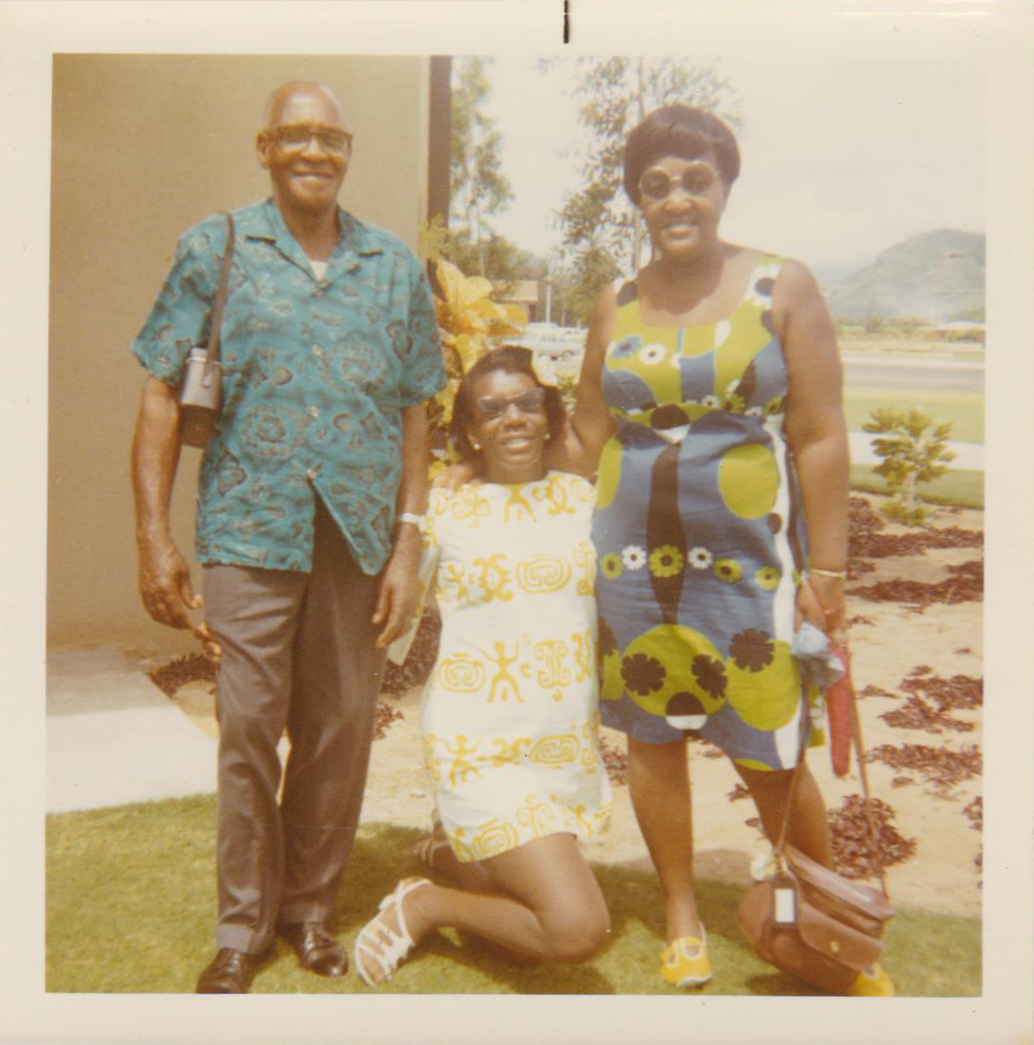

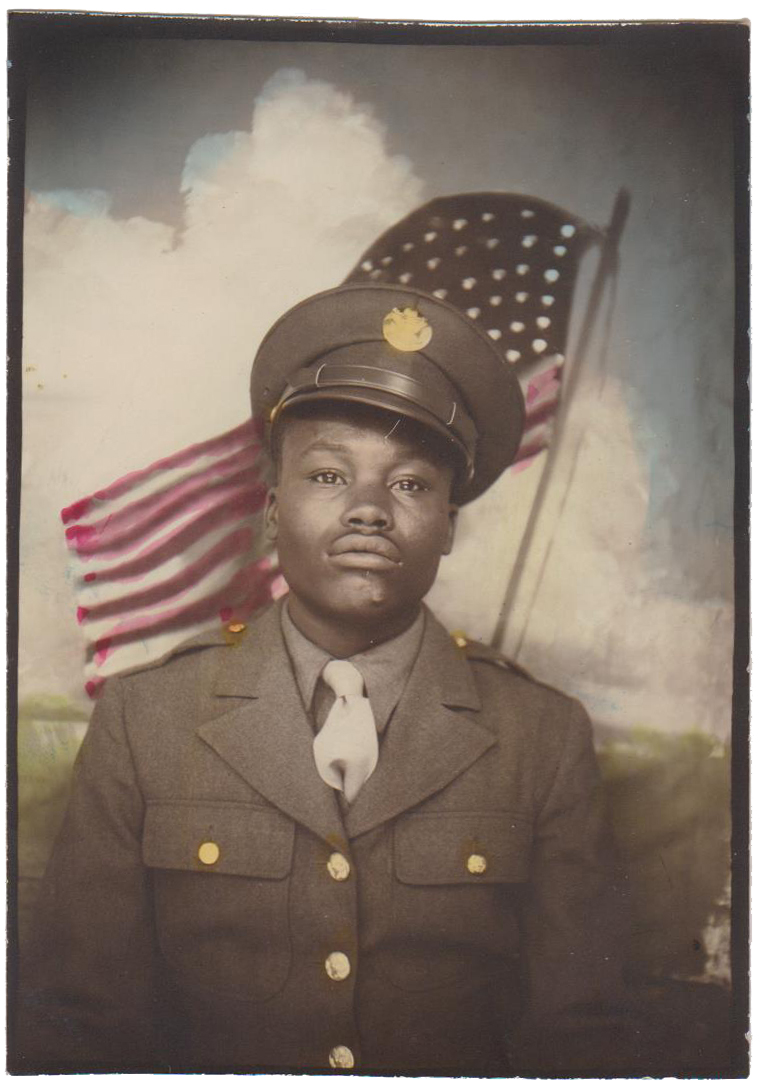

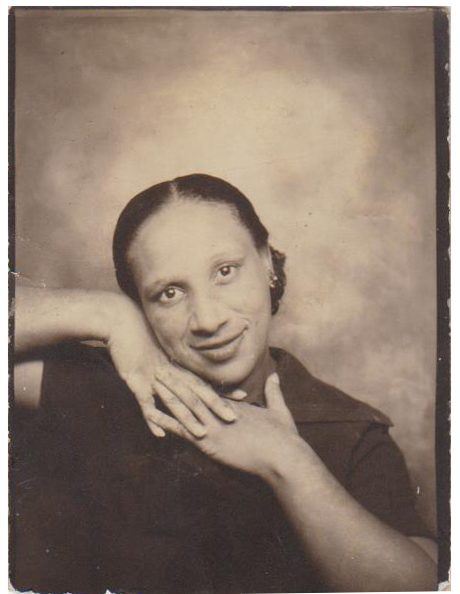

This post features photos of African Americans from the collection of Robert E. Jackson, with accompanying text by Jackson, an essay by Rafael Soldi, and poem by LaCole Foots.

"I collect beautiful and compelling images in all photo mediums and am honored to be able to share some of my collection of African American photos, both snapshots and studio poses. I am drawn to faces and a visual narrative which evoke some sort of strong emotion. These photos are no exception. They speak to the singularity of all of our lives—to the beauty of love, of laughter, of simply living. And for some of the people depicted here, life was likely not easy or carefree. But there is something which these photos elicit—some sort of universal pride or endurance which makes them approachable and knowable. And ultimately timeless."

—Robert E. Jackson

The African American Snapshot Matters

By Rafael Soldi

Representation of Black people in popular and vernacular culture throughout the last two centuries has been chiefly at the hand of White people. Without an outlet to represent one's self, the Black image took on generations of unfair interpretation, making snapshots of Black private life treasured tokens of American vernacular history today. Included here are snapshots from the collection of Robert E. Jackson, a wide range of images spanning from intimate and casual, to formal and solemn, from photo booths to color polaroids.

During the era of slavery, fear of rebellion manifested in the imagined notion of Black people as savages. Throughout the Reconstruction Era (1863-1877), Whites continued to oppress the Black person via caricatures and illustrated depictions of them as brutes. Though photography was invented in 1839, and by the 1870s it was a rather mobile process, depictions of Blacks in photographs were rare and largely controlled by Whites. It’s not until the twentieth century that snapshots and studio portraiture become more accessible and the Black person enters the vernacular tapestry of America through self-representation. However, this growing access to casual photography also resulted in an increased circulation of degrading images, such as harrowing depictions of lynchings, for example, which circulated as photo postcards. The early twentieth century also saw an increase of caricatured representation in movies and the media. D.W. Griffith's film Birth of a Nation (1915), told the story of a White Southern family from the days of slavery through the Civil War and into Reconstruction, the film showed images of Black brutes abusing their newfound freedom by perpetuating violence against Whites. Worse was their portrayal of the Brute as a sexual predator played by a White actor in blackface, while the Ku Klux Klan were portrayed as heroes.

Birth of a Nation (1915). Free Black shoots a White man (source)

Caricatures of Blacks as brutes continued throughout the first half of the twentieth century in the image of uncivilized barbarians in comic strips, TV, and commercialized products, and continued through the latter part of the century with Blacks being portrayed as thugs in Hollywood movies. Most prevalent in the twenty-first century has been the image of young Black men in the media, often presented as thugs and delinquents, as a aggressors instead of victims when they are murdered by White police. It has been astonishing the ease with which these cases are dismissed under the pretense that the White person “feared for their life,” even when there is ample evidence that the Black person was compliant and unarmed. This “fear” is the same fear that created the Black caricature of the 1860s, and is the same fear that leads a picture editor to choose an image of Michael Brown—who was killed by police in Ferguson, MO—pictured from below, as a towering figure with a stern look, sagging clothes, and a peace sign that White culture interpreted as a gang sign, versus the more empowering image of him in a graduation cap and gown—the brute is an easier sell. During the Trayvon Martin trial, the hoodie became a cultural symbol. This has lead to heightened attention to how the media chooses to present Black males; in 2014 a Twitter campaign drew over 200,000 users to repost the hashtag #iftheygunnedmedown, which poses the question “If they gunned me down, what photo would you use?” The choice to always depict the Black male as an aggressor is, in fact, a choice; just as the choice the highlight a white rapist's athletic accomplishments over his crime is also a choice.

James Van Der Zee, Wedding Party, 1923. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

There is little public documentation about the private lives of African Americans in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when their social transactions took place for the most part outside of public view and often away from the camera's lens. In 1916 James Van Der Zee established the Guarantee Photo Studio in Harlem, quickly becoming one of the most prolific and important African American photographers in the twentieth century. Van Der Zee’s studio portraits and documentation of Harlem’s people presented a refreshing alternative to the caricatured vision of the Black person and his photos remain a creative expression of Harlem’s finest: musicians, performers, celebrities, and regular people with a sense of pride, personal history, empowerment, and self-assurance.

Van Der Zee’s career declined as portable personal cameras became popular and the need for a formal studio photographer diminished. However, the introduction of personal cameras provides us now with an invaluable archive of intimate snapshots that peer back into history and allow us to better understand and celebrate the lives of Black people in America. These snapshots are akin to oral histories, they put Black people at the helm of the camera, as storytellers of their own lives. They choose what to share and shine light on the beauty and dignity of the human condition. Vernacular snapshots featuring Black people are scarce, perhaps because they had less access to cameras, or perhaps because Black families place great value on their histories and are less likely to discard them. So the few that exist are important documents in telling a complete story of the American people.

Many contemporary artists have used snapshots in their work, be it for formal or conceptual reasons. The 1980s and 1990s saw the work of Lorna Simpson, one of the most notable contemporary artists of our time, come into notoriety. Simpson’s practice, which includes photography, text, film and video, explores issues of race, gender and sexuality, often in the broader context of particular socio-political moments. Photo Booth is a work by Simpson made up of fifty 1940s photo booth portraits, predominantly depicting black men, and fifty drawings of the same size. She has said, ‘The ’40s, in American culture, were a tough time in terms of life, work, Jim Crow laws, segregation and lynchings. And so the nostalgia of how beautiful these portraits are is one thing, but the context of the era is important with respect to what was endured at the time’.

Photo booth images are particularly interesting because the performative act of taking them—one makes a choice to step into a small box, close the curtain and perform. Immediately this becomes an intimate moment, and the flash captures the likeness of the sitter as they wish to portray themselves in that moment, alone in that booth. This urgency to mark time, to create a record of one’s self, to leave a trace is on par with Simpson’s practice, which often places her own body against the story of Blackness in America to create a direct link between the present and the complex history of American race politics. Similarly, in Photo Booth, the introduction of her own drawings juxtaposed with the photographs, which are machine-made self-portraits produced by the sitters themselves, complicates the question of artistic ownership and further weaves her identity—and that of Black people today—with that of those who came before her.

As one scrolls through these wonderful snapshots from Jackson's collection, it is hard to ignore the affection, innocence, determination, style, passion, poise, humor, pride, and aspiration found in them. Jackson's words above said it best: "[these photos] speak to the singularity of all of our lives—to the beauty of love, of laughter, of simply living. And for some of the people depicted here, life was likely not easy or carefree. But there is something which these photos elicit—some sort of universal pride or endurance which makes them approachable and knowable. And ultimately timeless."

Lorna Simpson, Photo Booth. Courtesy Salon 94, New York

Within

by LaCole Foots

I had almost forgotten

we existed outside of riots

We'd burned brightly

beyond the fires

Carrying more than ropes

and false hopes around

Our necks

Cocked sideways holding up

the sun

On our shoulders

And smiles white, bright, yellow

Brown

Is its own beauty

Not merely as a contrast

Not a difference in resolution

Our flesh has always dictated the prism

If mere survival is resistance

If simply living is a contradiction

If our greatest nuisance is our subsistence

Then let the rebellion thrive in our marrow

Their yesterdays still threaten our tomorrow

But todays were built by our blood

Within, warm and vibrant

Not without life

All images © Robert E. Jackson unless otherwise noted