Q&A: Randi Ganulin

By Hamidah Glasgow | December 26, 2019

Born in Los Angeles, Ganulin completed general studies at UCLA before studying printmaking and illustration at the Rhode Island School of Design, finishing her BFA in communication design at Otis College of Art and Design. She was awarded the Javits Fellowship for her graduate work in photo-based media, earning an MFA from Otis in 1996. She has exhibited nationwide, and her work is included in the collections of the New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe, NM, the Griffin Museum of Photography, the Center for Fine Art Photography, the cities of Kent and Tacoma, WA, and varied private collections. She lives with her family just east of Seattle and is an adjunct faculty member in the Fine Art Department at DigiPen Institute in Redmond.

“What I see around me is a mix of the disturbing and the beautiful. I’ve always sought a way to make sense of it all through my art. How can we still believe in the power of beauty, when so much political and social hype and terror of all kinds surround us? I’m concerned about how our fixation on instant gratification— capitalism seems to rely on it— is affecting the planet. I feel artists have a responsibility to educate, question, and probe the society they form a part of. Art of all kinds can do this, whether it’s art for galleries, museums, or public art.” _Randi Ganulin

Hamidah Glasgow: You’ve been an artist for many years, what would you tell your younger artist self?

Randi Ganulin: I would’ve reminded myself of the Joseph Campbell adage to ‘follow my bliss’ a whole lot sooner. Instead of worrying about making a living—in my case, I chose graphic design as a proxy for making art—I would tell her to be brave and commit to her fine art practice.

I might also introduce her to the Sister Corita Kent/John Cage “10 Rules.” I give all my students a copy of them on the first day of class. I especially like Rule #8: “Do not try to create and analyze at the same time. They are different processes.” Dream and experiment while you’re in create mode. Steer clear of analyzation and judgment; just tinker. Then sit back and take a look at your work. Is it doing what you thought it would do, or something different? These are two different states of mind. I’ve found it’s usually best to keep some separation between them. Though I can’t say I always find that easy to do.

HG: Committing to a fine art practice is difficult for many people. Our society doesn’t value that pursuit until someone is “famous” and then we are ok with them being an artist. How do you advise your students to move forward?

RG: Believe in yourself! There is no Plan B.

HG: Tell me about your path as an artist, and what events or inspiration brought you to where you are now?

RG: The fact that I am adopted, and a woman, has formed me as an artist. As an adoptee, I realized early on that I was very different from my family in temperament. Through no fault of their own, they had no idea of what made me tick. My mother particularly saw my sensitivity as a shortcoming, and let me know it in no few words. As a result, I never felt certain of how I fit into my environment, and, particularly as a girl growing up, I felt a strong need to please, to conform to fit in. I was a fish out of water for many years… a chameleon maybe is a better metaphor… which is the exact opposite of what it is to be an artist. This unresolved tension between wanting to be loved and understood, and feeling that I was somehow betraying myself…that I simply had to find my voice, or I’d end up disappearing altogether… a ghost of myself… this is what propelled me into making art. Art was the one place I could totally be myself.

The ghost image reminds me… this past summer, I read “The Woman Warrior” by Maxine Hong Kingston. I found I could relate to her story of growing up in a Chinese-American household. Many of the same throughlines of conforming/non-conforming, and of being misunderstood. Only she winds up using her voice, decisively, yelling, in fact. It’s a stunning read.

HG: Has being adopted affected other work that you’ve made?

RG: No, not as directly. As I said earlier, that work represented a particular time and place in my art practice. Most of my work has concentrated on the sublime, the terrible beauty of life, and its fragility.

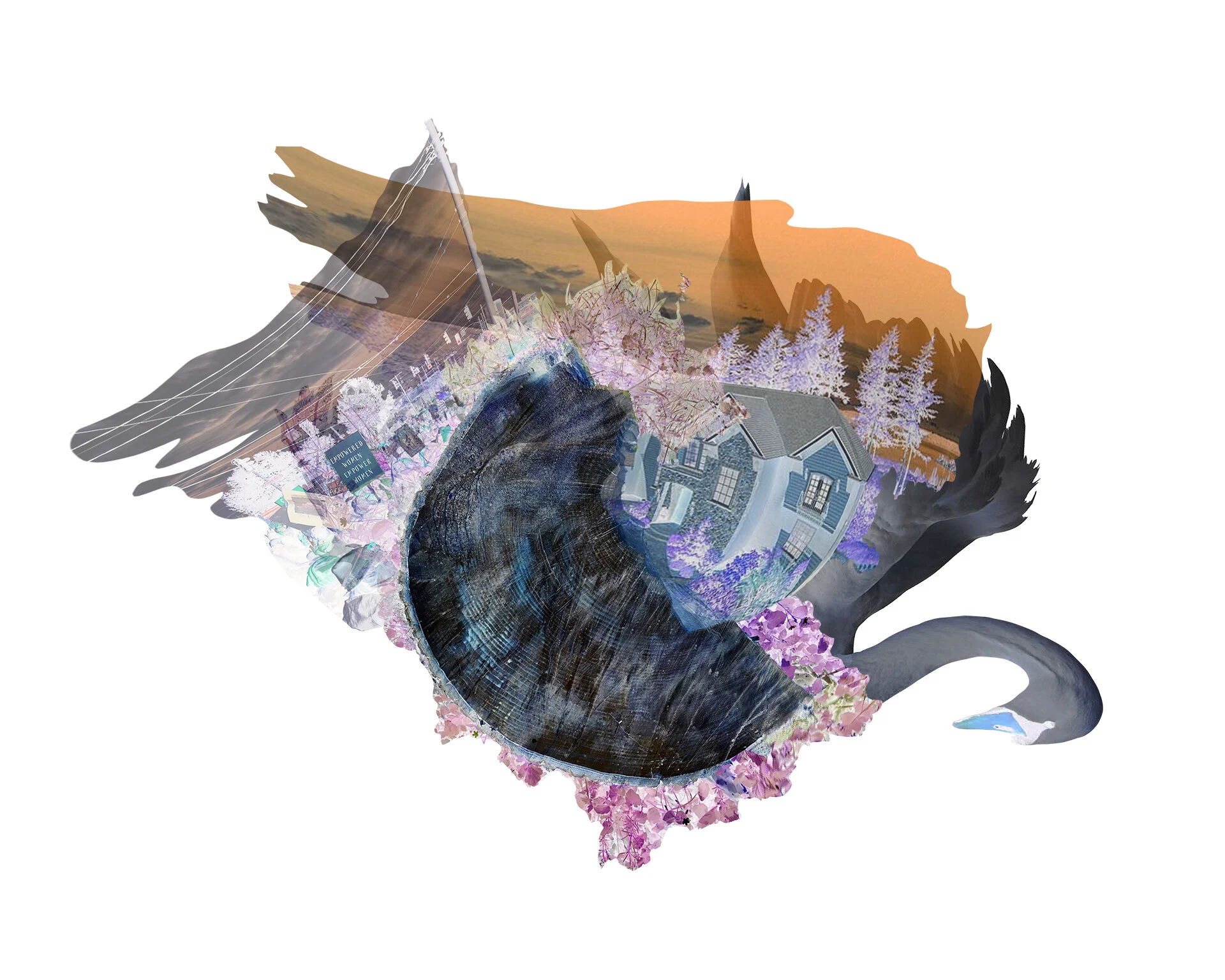

Black Swan

HG: A good deal of your work engages with environmental issues, what motivates you to pursue this vein? Your focus on the environment goes back many years; how did you get started on this topic?

RG: I’ve always been addicted to the news. Starting back in the ’90s, when I was a grad student, I began to collect pictures of natural disasters. At that time, there was little or no internet… I looked for photos in the newspaper, Time and Newsweek, mostly. This collection formed the basis for “Paired Disasters,” in which I joined a found photo with a close-up image of my home environment: for example, a burned dish of lasagne paired with an image of a burning sportscar from a magazine. I began to find more and more pictures of forest fires, clearcut forest, car bombings in Beirut, the Oklahoma City bombing. I asked myself what my role was as an artist to integrate this stuff: How does one make sense of good and evil? What, exactly, is an “accident?”

I was inspired by vanitas paintings of the Dutch baroque and made some pieces in this vein while still in school. Eventually, I had the idea to compose still lifes depicting various events related to the environment, using thrift store items to represent the earth: a paint bucket, a gravy boat, a dutch oven. This work became “Vessels: Environmental Parables.” I’ve continued to make work about the environment; it’s essential to keep it visible. It needs to be acted on more than ever.

HG: Your work engages with many issues from the self, environmental issues, and transcendence. How would you define what motivates your work?

What I see around me is a mix of the disturbing and the beautiful. I’ve always sought a way to make sense of it all through my art. How can we still believe in the power of beauty, when so much political and social hype and terror of all kinds surround us? I’m concerned about how our fixation on instant gratification— capitalism seems to rely on it— is affecting the planet. I feel artists have a responsibility to educate, question, and probe the society they form a part of. Art of all kinds can do this, whether it’s art for galleries, museums, or public art.

I believe in the power of art to do this, particularly public art. In August of 2018, I spent the better part of a month on a site-specific project at a park in Seattle overlooking Puget Sound. While I wove mason twine, wire, and photo transparencies of forest fires and historic timber industry images in and around a felled tree trunk, wildfires raged all around Seattle, from Portland to Vancouver. The sky was filled with smoke while I worked. At times, I had to wrap a bandanna around my face to keep from inhaling the smoke. All kinds of people stopped to talk to me and asked about what I was doing and why. I loved the curiosity my work inspired. The timing couldn’t have been more awful— or more perfect.

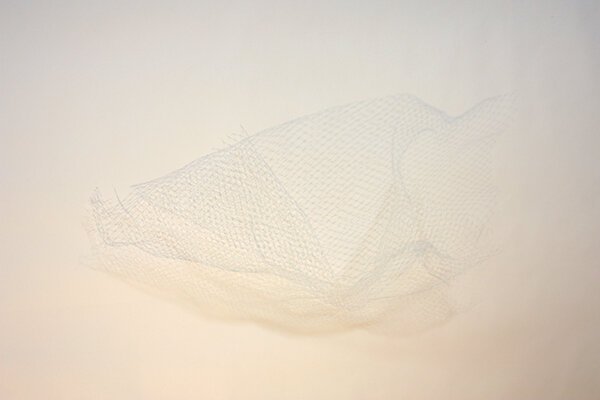

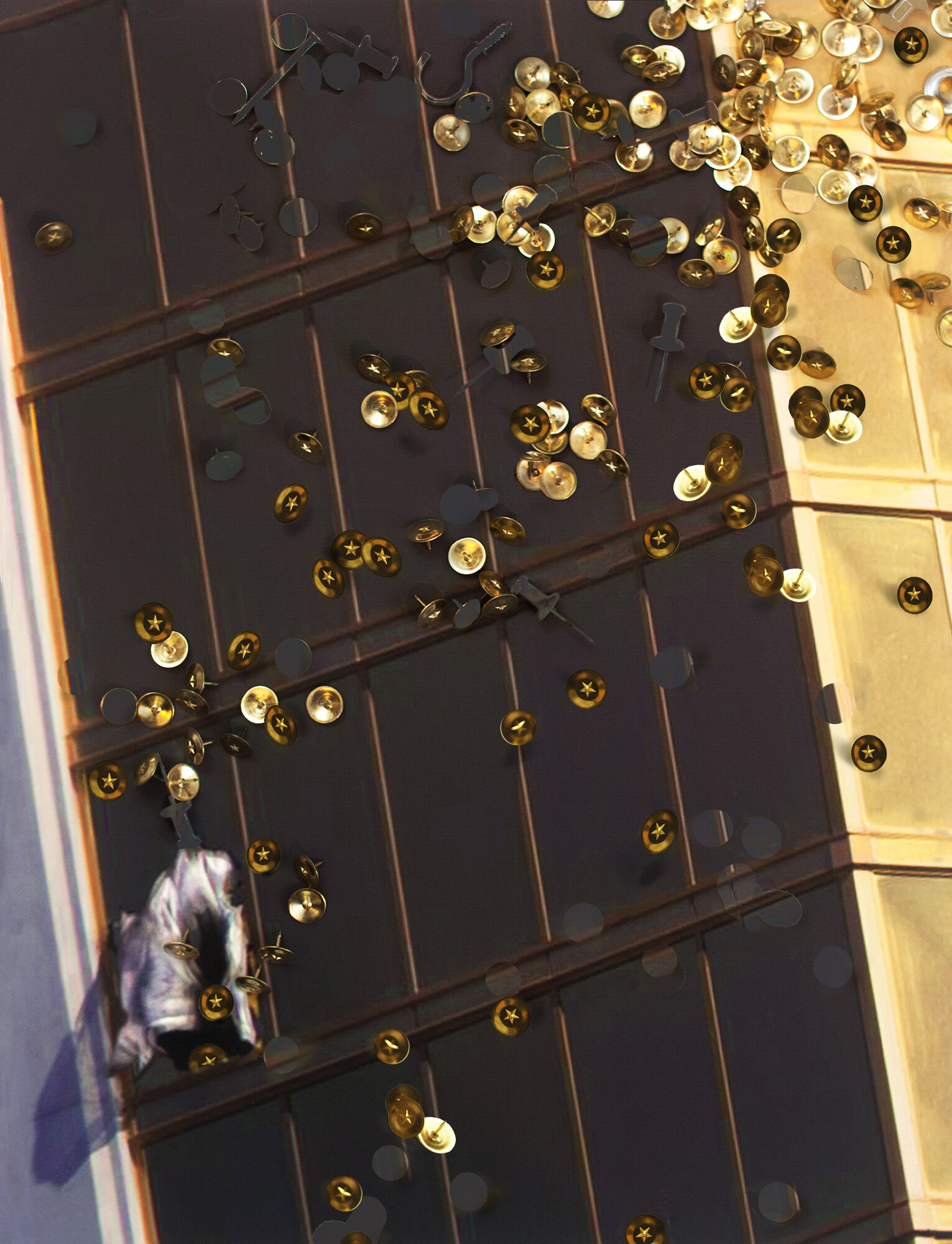

Lodestar

HG: Have you created other public artworks? If so, what were they about?

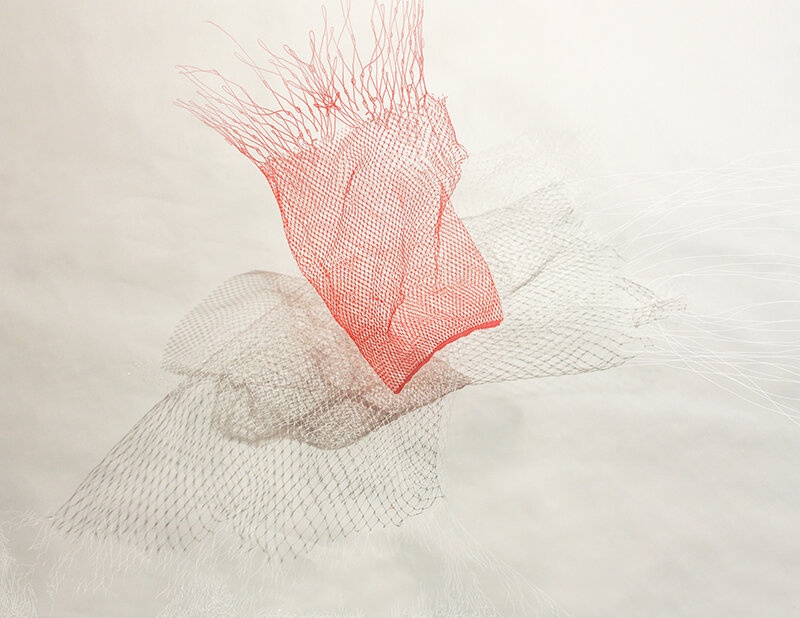

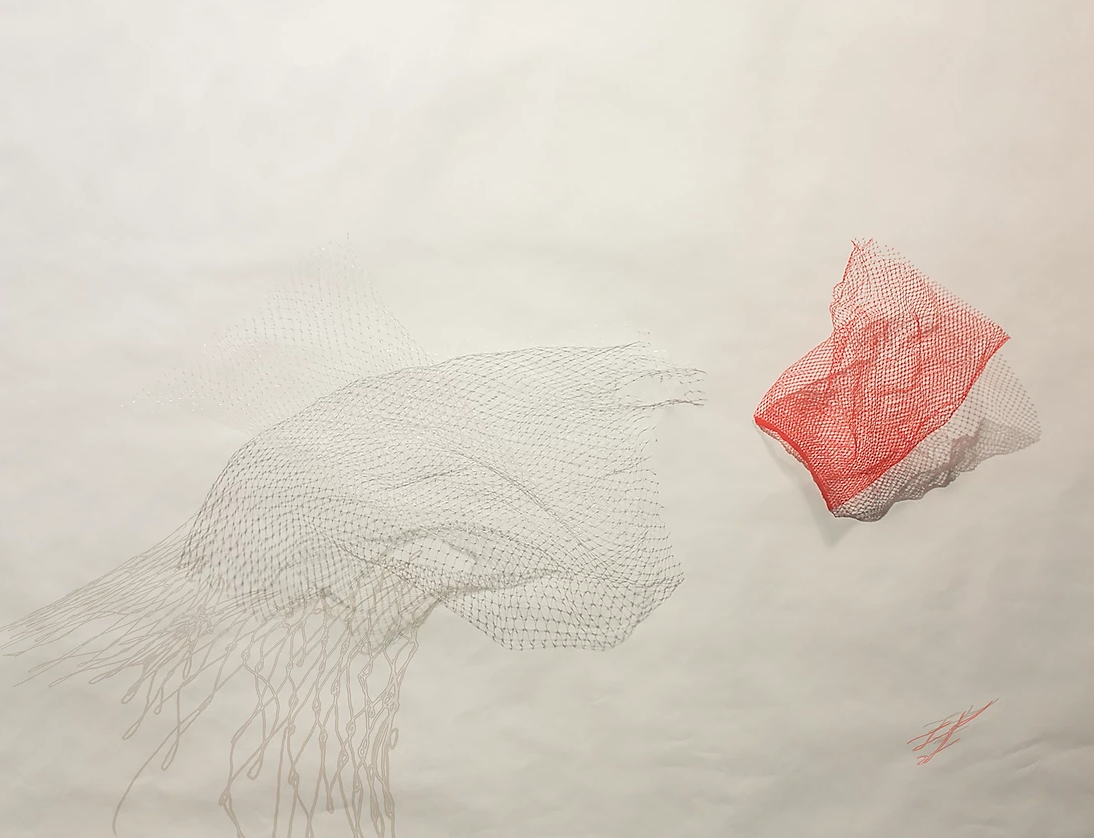

RG: I’ve been making public art since graduating Public Art Boot Camp in late 2017. It was a fantastic experience, organized by Elisheba Johnson and Marcia Iwazaki of the Seattle Office of Arts and Culture. Along with the piece I described earlier, “Carapace,” made for “Heaven and Earth X” at Carkeek Park in Seattle, I’ve completed temporary commissions for the 2017 Seattle Sculpture Walk and 2018 Shunpike Storefronts. The latter two involved the use of nets. “Lodestar,” which was installed at Seattle Center, included two large intertwined commercial fishing nets that I wired hundreds of mirrored paillettes— basically, large, flat sequins— into. My inspiration was the idea of Indra’s Net, a cosmological depiction of the world. “Arterial” also used nets— the small-scale nets used for bagging produce, like onions and potatoes. I made cyanotype contact prints of these, scanned, cloned, and spliced them digitally, then had them blown up and printed onto commercial-grade poly film— the same material used for fast-food menu signage, in cyan blue and red, colors referencing the human circulatory system.

HG: I’m fascinated with the Inanna work and how you’ve used your body as the palette or starting point of each image. When you started this work, did you think about what the work means on a white body? Are there depictions that you steered clear of because of your whiteness?

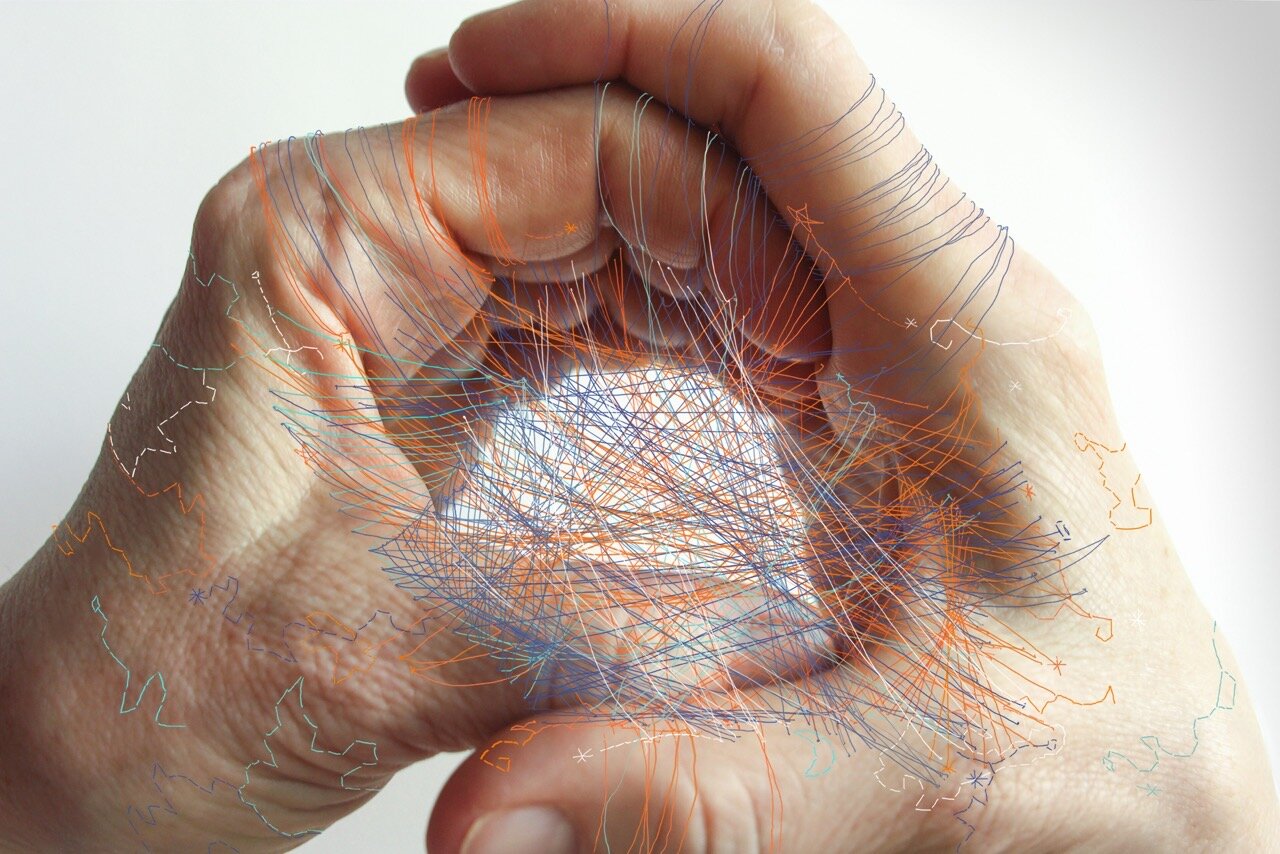

RG: “Inanna” was motivated by the need to ground myself in my art practice again, after the initial years of bringing up my children (I have two, a daughter and a son.) I made a conscious decision to use my body as a form of self-portraiture. The images also draw from mythology, particularly from the ancient Sumerian myth of the goddess Inanna. So the work started from a personal point of view, with the image “Palm,” which depicts Sea Holly, a type of thistle, spiky and tough, growing out of my hand. It’s meant as an homage to the life force, which is truly a mystery. (and like the thistle, spiky and tough, yet pliable and unrelenting.)

I wanted to make images that were an unapologetic acknowledgment of the power of spirit— something that was looked down on as “nostalgia” by my primarily conceptual instructors in grad school. In “Haven” and “Runoff,” I wanted to own my middle-aged body as strong and resilient. “Gale Force” goes a step further— I’ve taken the gesture of da Vinci’s St. John the Baptist, this sort of ultimate old-white-man patriarchal religious figurehead— and make the gesture using my own hand, surrounded by oceans of consumer goods, a dandelion growing from my finger, pointed toward heaven.

Sometime in the last year and a half, I stopped making work for this series. I felt the work was getting myopic; I became tired of depicting myself. You make a good point— if I were to continue work in this vein, I think I’d have to step outside of myself and depict women, not woman— good food for thought.

HG: Can you be a stand-in for Women?

RG: It’s a good question. Like I said earlier, I try to let myself make things, and then sit back and look at what I’ve made more analytically. What started as self-portraiture and owning the depiction of my own body morphed into something else.

HG: What are you working on now?

RG: Since late spring, I’ve been experimenting with printing on different substrates— rice paper, for one— and stitching these photos together, into paper quilts made up of fabric and wallpaper patterns, found images of icebergs and glaciers. Another project I’m working on involves photographing mounds of found plastic bags and merging them into something larger. It may wind up as installation as well as photographic objects… we’ll see. I’m working on a public art proposal or two. I’ve been hampered a bit by a flood that hit my studio a couple of months ago. I’m putting it back together piece by piece. I’m finally typing this on my laptop, at my desk, just reinstalled yesterday. I feel so lucky to have my workspace back!— But most everything still needs to be unpacked.

HG: Do you have a favorite body of work that you’ve created? Tell me about that work.

RG: I’m very proud of “Paired Disasters.” It’s a complicated body of work, as you know, …it’s not necessarily my most accessible work. The images that form the basis for each diptych range from natural disasters to massacres, each visually bound together with a close-up image of my home environment. I’ve been working on this project for a long time; it has evolved over the years. Some of the pieces are more successful than others; some are more obtuse, others more direct, but I feel the work has legs. Some disasters I treat sardonically— how can one understand the motivations of the Mandalay Bay Hotel killer, the ease with which he purchased an arsenal of guns?— But most images I simply try to honor. I don’t know if I’ll ever be finished with it.

HG: Are the paired disasters a method of making disasters and human suffering that you see/find in the news real for you and your life? It is so easy to see these disasters as happening to other people and not me or you.

RG: Yes, exactly. I was/have been trying to find a way into empathy. It’s so easy to become desensitized to these images. Working with them is a balancing act: Not to pretty them up, and not to gloss over them either. Which is why I also let some of them be sardonic, or use black humor.

Earlier this year, Zemie Barr put together a terrific show called “Double Vision,” at Gallery One in Ellensburg, WA. She chose five images from five of last year’s Blue Sky viewing drawers artists (Laura Kurtenbach, Jennifer Zwick, myself, and two others) then asked 25 different poets to write an ekphrastic piece in response to each image. The result was amazing— the poems complemented each of the diptychs, enlarging their meaning and tone. I’ve rarely been to an opening that I felt more engaged in by the public. It was a great feeling, one that I still savor.

HG: Thank you for your time!

RG: Thank you!

All Images by Randi Ganulin