Q&A: priya kambli

By Jess T. Dugan | June 9, 2016

Priya Kambli was born in India. She moved to the United States at age 18 carrying her entire life in one suitcase that weighed about 20 pounds. She began her artistic career in the States and her work has always been informed by this experience as a migrant.

She completed her Bachelor of Fine Arts degree at the University of Louisiana in Lafayette and continued on to receive a Masters degree in Photography from the University of Houston. She is currently Professor of Art at Truman State University in Kirksville, Missouri. In 2008 PhotoLucida awarded her a book publication prize for her project Color Falls Down, published in 2010.

Jess T. Dugan: Tell me about your ongoing series Kitchen Gods. How did this series begin and how has it evolved over the past several years?

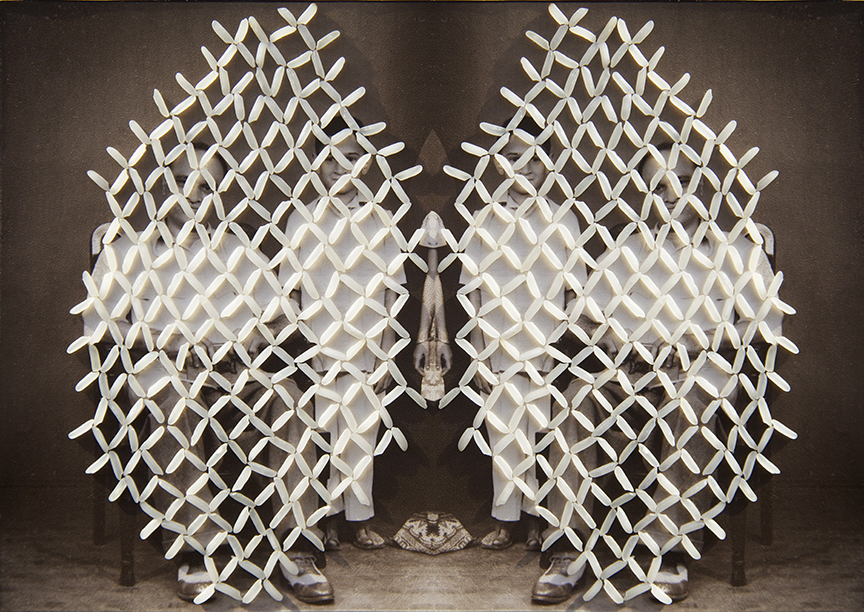

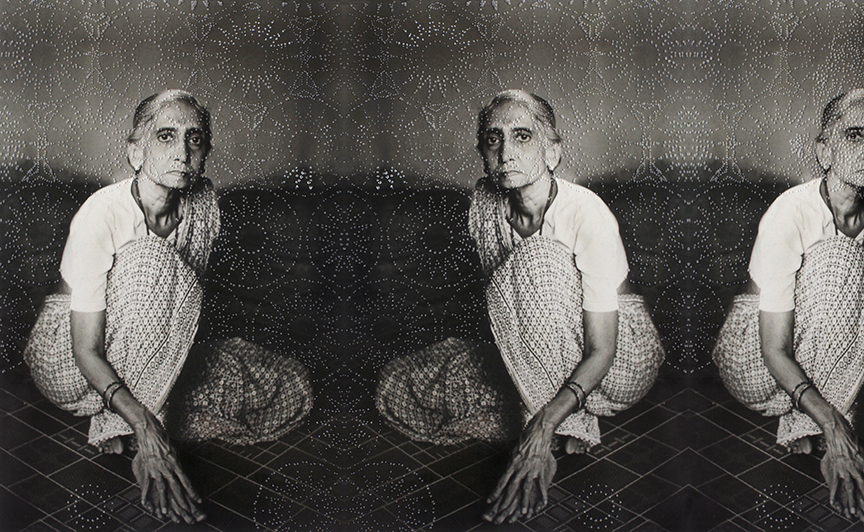

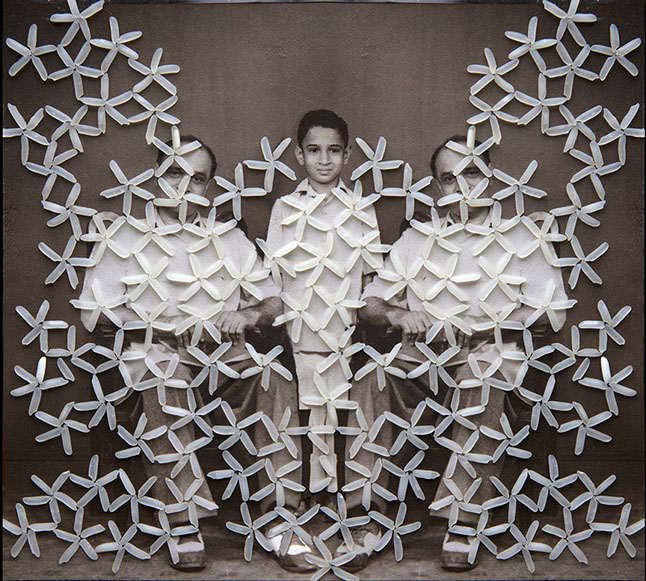

Priya Kambli: Kitchen Gods references one of my most startling early childhood memories; finding one of my father’s painstakingly composed family photographs pierced by my mother. She cut holes in them so as to completely obliterate her own face while not harming the image of my sister and myself beside her. These marred artifacts have formed a reference point and inspiration for this body of work. I am fascinated by how the presence of a meditated mark alters and complicates the read of an otherwise mundane family portrait.

My artwork is intrinsically tied to my own family’s photographic legacy. At age 18, I moved from India to the United States, a couple of years after my parents passed away. Before I emigrated my sister and I split our photographic inheritance arbitrarily and irreparably in half - one part to remain in India with her and the other to be displaced along with me, here in America. For the past decade my archive of family photographs has been one of my main source materials in creating bodies of work which explore the genre of personal narrative.

Dada Aajooba and Dadi Aajis, 2013, from Kitchen Gods

Over the course of working, I have realized while my relation to my old, unique photographic prints is emotional, as an image-maker I am also aesthetically drawn to their seemingly magical ability to render light and form in various subtly changing values. Having worked intimately with these older film-based photographic prints I found that a certain alchemy was lacking in my own digital inkjet prints. This was not necessarily an issue of image resolution (number of pixels per inch or granular width of photosensitive chemistry). Rather it had to do with the tactile qualities of the photographic object; the fact of its having been touched and brought to life by hand with glowing tones and beautiful grain. Therefore, I am currently working directly with and on the family photographs.

Muma's, 2014, from Kitchen Gods

JTD: Your work is heavily influenced by your experience of immigrating to the United States, carrying your “entire life in one suitcase that weighed about 20 lbs.” I almost don’t know where the question lies here, as that is such a huge part of your identity and your experience in the world. I think we each have an unrelenting drive that forms our work, something we keep trying to understand or explore but are never fully able to resolve. Do you think this is true for you? What would you identify as the thread that links your various bodies of work?

PK: When I migrated to the States at age 18, in the wake of my parents’ death, I really was quite lost – searching for some way to make good. I hadn’t always known I would be an artist – it came to me late – at a point in my life when I very much needed to find my own way in the world. So yes, making art has an existential urgency for me.

Having worked with my archive of family photographs for close to a decade, I do question my need and desire to continue working with them. I think for me this need embodies my intention to create for the future what our forebears made for us: I treasure my archives of old family photographs. I want to create lasting one-of-a kind photographic prints that will compel future viewers to hold, examine, and cherish them.

My need to re-contextualize the familial qualities of my family photographs for my own artistic and creative purposes, as a way of embellishing my past and connecting it to the present, is what ties all the bodies of work together.

Muma, Baba, Sona and Me, 2011, from Color Falls Down

JTD: Photography is inherently linked to memory, but in your work, there are additional layers of memory and loss. I found this passage, written about Kitchen Gods, especially poignant:

My work is rooted in my fascination with my parents – both of whom died when I was young. Therefore for me these family photographs hold even more mythological weight. In my work I labor to maintain my parents the way Indian housewives do their kitchen deities. I also strive to connect the generations, my ancestors and my children, who have been separated by death and migration. Like my mother, I alter these photographs to modify the stories they tell.

I am particularly struck by this desire to connect your ancestors and your children through your photographs, a task that is obviously unrealizable in the physical world but becomes possible through your work. How do you navigate these layers of memory and loss, connection and separation, when creating your work?

PK: Yes, I am concerned with the past that is lost to me, but as I’ve said, I am also concerned with the future, and the losses that will come. Inevitably I too, or at least my experience as a migrant, will become mythologized by my children and then their children. Making artwork about the past is a way of creating a first draft of the present as well.

Muma Baba and Me, 2008, from Color Falls Down

JTD: Your work is very labor intensive, though I imagine that it must be somewhat cathartic to make. What is your process for actually creating each image? What kind of emotional space is necessary for you to make this work? To what extent do you involve your family- your husband and your children- in the process?

PK: Yes, my work is labor intensive, verging on obsessive. And yes in some ways it is cathartic. The process of making the images is simple. I work directly with and on my family photographs building tableaux and memories - embedding marks and patterns in and on them. I use patterns as a way of communicating identity and culture, but also a way of obscuring information. In fact my use of pattern has been described as a form of fenestration- though the patterns obscure the image they also create windows through which underlying structures are revealed.

My choice of materials, methods and approach are usually informed and driven by specific details within the family photographs themselves. I gravitate to materials that are humble, my preference being for things that are domestic and modest in nature - grounded in everyday use.

Me (Flour), 2009, from Color Falls Down

I work in the chaos of my house. My husband, who is also an artist, is extremely supportive of my creative practice. I also have two kids, one 10 year old boy and a super gregarious 5 year old daughter; I am constantly being interrupted. Recently my 5 year old daughter asked me if she could have flour (one of the materials I use to embed patterns in my work) so that she could play with it like I do.

I also have come to a realization that I am a rather poor juggler when it comes to juggling my various roles- artist, academic, parent and spouse. I also am extremely focused and therefore can cater to just a role at a time. Which means something always suffers.

JTD: Tell me about your newest project, On White, which is an “exploration of the physicality/materiality of snow; the forms it takes, the way it responds to light.” How did this project begin and what are the ideas and questions that inform it?

PK: This series has obvious connections as well as discontinuities with my other bodies of work. There is less of an emphasis on my family photographs, which often don’t even appear in these pieces. But the sense of play continues in this series, through the creative appropriation of the material of the snow itself, that is exactly parallel with my use of flour, rice, patterns, etc. in my other work. The snow fills in gaps obscuring and revealing information by the occurrences of the process of play.

Shapes, 2014, from On White

JTD: As you know, the Strange Fire Collective was formed specifically to highlight artists of color, female artists, and LGBTQ artists. What challenges have you faced as a woman of color making work about your culture and your family?

PK: My experience as a minority and a woman in America is a little atypical, as I did not grow up here and the issues are dominated by the overarching topic of immigration. My creative work has been informed by my own emigration and thus has always grappled with the challenges of cross-cultural understanding. One of the challenges about making work that deals with cultural identity viewed through the personal lens is finding appropriate venues for the work. I am constantly given a run around in terms of where to show the work. I get the sense that gallerists and museum professionals see the work and think “this is good, but it requires some educational outreach for the audience.” In fact my work is frequently curated into non-profit educational gallery spaces precisely because of its potential to start a dialogue about cultural differences and universal similarities. These experiences are always great but I don’t know if that gives the work its full due as artwork.

JTD: Where do you find inspiration? What other artists are you interested in?

PK: I find a lot of inspiration in old photographs, patterns, and simple materials – as well as the crazy experiments my children are always conducting. Often, one of them will create some playful juxtaposition that is a perfect response to the materials around the house that are a big part of my own vocabulary – and I will just appropriate some of that fun stuff into my own work.

As I mentioned earlier we live in a small rural mid-western town. Art is therefore mostly accessed through the internet. When we travel, which we do often thanks to our academic life, we always visit galleries and museums. Some of the artists whose work I find fascinating in no particular order are: Carolle Benitah, Birthe Piontek, Jessica Hines, Susan Worsham, Viviane Sassen, Larry Sultan, Mona Kuhn, John Stezaker, Abigail Reynolds, Olivia Parker, Mona Hatoum, Rachel Whiteread, Cy Twombly, Agnes Martin, Hellen Van Meene, Letha Wilson.

JTD: What’s next for you as an artist? What kind of projects are on the horizon?

PK: I am very excited to start my year-long sabbatical leave in August. The purpose of my sabbatical project is to expand my creative practice and professional expertise, addressing the aesthetic quality and archival viability of my photographic prints, while expanding the photographic curriculum at Truman State University. I am looking forward to making work, uninterrupted.

Some tangible projects on the horizon are an upcoming two person show at the Filter Photo Space in Chicago, IL and two group shows at the Griffin Photography Museum in Winchester, MA.

All images © Priya Kambli