Q&A: MYrA GREENE

June 20th, 2019 | By Zora J Murff

Myra Greene uses a diverse photographic practice to explore representations of race. Greene is currently working on a new body of work that uses African textiles as a material and pattern to explore her own relationship to culture. She received an Illinois Arts Council Fellowship in Photography and has completed residencies at Light Work in Syracuse New York and the Center for Photography at Woodstock. Her work is in the permanent collection of Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, The National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, and the Princeton University Art Museum. Myra Greene's work has been featured in national exhibitions in galleries and museums including The New York Public Library, Duke Center for Documentary Studies, Williams College Museum of Art, Spelman College Museum of Fine Art in Atlanta, Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco, and Sculpture Center in New York City. Myra Greene was born in New York City and received her B.F.A. from Washington University in St. Louis and her M.F.A. in photography from the University of New Mexico. She currently resides in Atlanta Georgia, where she is an Associate Professor of Photography at Spelman College.

Myra’s work is currently on view in the group exhibition Go Down Moses, curated by Teju Cole, at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago. She also has an upcoming solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Georgia. The exhibition is a part of the WAP Fellowship at MoCA GA.

Zora J Murff: My partner saw an exhibition of your work in Chicago back in 2016 and bought me a copy of My White Friends. I’ve been wanting to connect with you since, so I’m excited that this is finally happening! Let’s get started by introducing you to our readers.

Myra Greene: Well first off I am happy we could make this happen too. I think the work of Strange Fire is so relevant and important at this time.

I grew up in NYC in Harlem, went to a private white catholic white high school where I excelled at sports and photography. Went to Washington University in St. Louis to get my BFA in photography, returned to NYC to live in Brooklyn for a few years before heading West to University of New Mexico for my Masters. My first teaching job happened right away, and was at Rochester Institute of Technology for 5 years, then taught at Columbia College Chicago for 10 years and now I am in Atlanta starting up the photography program at Spelman College.

Since grad school, I have been interested in photography as a technology of seeing, as a unique material, as a visual language. In the last years, I have started to work with fabric and textiles as well.

ZJM: I love that you’re starting up the photography program at Spelman College. I want to ask you about your experience there so far, but we’ll save that for the end of the interview. Last semester, I led a graduate seminar, and we listed to Scene on Radio’s Seeing White series as a way to begin discussions about race and representation in contemporary art. You were interviewed for Episode 42: My White Friends. What was it like being asked to participate in the podcast, and what importance do you feel the entire series Seeing White holds when broaching the topic of whiteness?

MG: It was an honor to be asked to participate. And at the time I really didn’t know what the whole project would become. John Biewen called me, and we talked about what he envisioned for the project. He had been referred to me by Courtney Reid- Eaton as they all work in Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University. I was able to exhibit almost all of My White Friends (MWF) there and give a talk. It seemed at this stage he was still forming the idea and becoming comfortable with even himself talking about whiteness and in turn its visual representation.

The oddest part was the recording of the conversation. It was all via a phone call, with a sound engineer in my home recording me speak in my closet… I have never met John in person, but he made me somewhat comfortable. Also odd to hear the conversation re-edited, friends offering insights and commentary of your own art process and project afterward. In the end, it has brought the idea of MWF to a larger community than the project has seen.

What is interesting to me about Seeing White and the podcast is whiteness examining whiteness. A part of the conceit of MWF project is that recognizing whiteness as a visual category. It makes people rather uncomfortable. But in reality, I have been asked to talk, engage, make work about my blackness for years. That interior contemplation of how the history, description, and stereotypes of my racial identity effect me as an individual is an intellectual loop that I am constantly engaged with. I commend John because I think that podcast is one of the first times I have actively heard someone process whiteness in the same ways. It is a messy but rewarding thought experiment, that be done by everyone… regardless of cultural background.

When I made MWF, for many of the sitters, good dear friends of mine, it was the same thought experiment… being approached because of their racial identity. Many had never been approached that way before… and had to reconcile the idea of being forefronted as a racial category. It started many interesting conversations and revelations.

J.R., Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, 20”x20”, Digital Print, 2012

ZJM: It’s an exciting project, and I feel commendable as well. My class had the same experience. In one of their presentations, a student asked the question, “How are you attached to your whiteness?” It took some time for people to figure out how to even begin answering that question.

I feel that My White Friends is important because of the role photography has played in cataloging those who were considered “others”. I’m thinking about daguerreotypes of slaves created by J.T. Zealy for Louis Aggasiz, Edward Curtis’s portraiture of Native Americans, etc. You critically turn the lens—reversing our gaze. Backtracking a bit, your earlier works delve into race by looking at black/brown bodies. I’m interested in hearing your thoughts about photography, representation, power, and gaze; how you came to the conclusion to begin photographing your white friends to talk about whiteness; and how you think your work fits into this particular historical narrative.

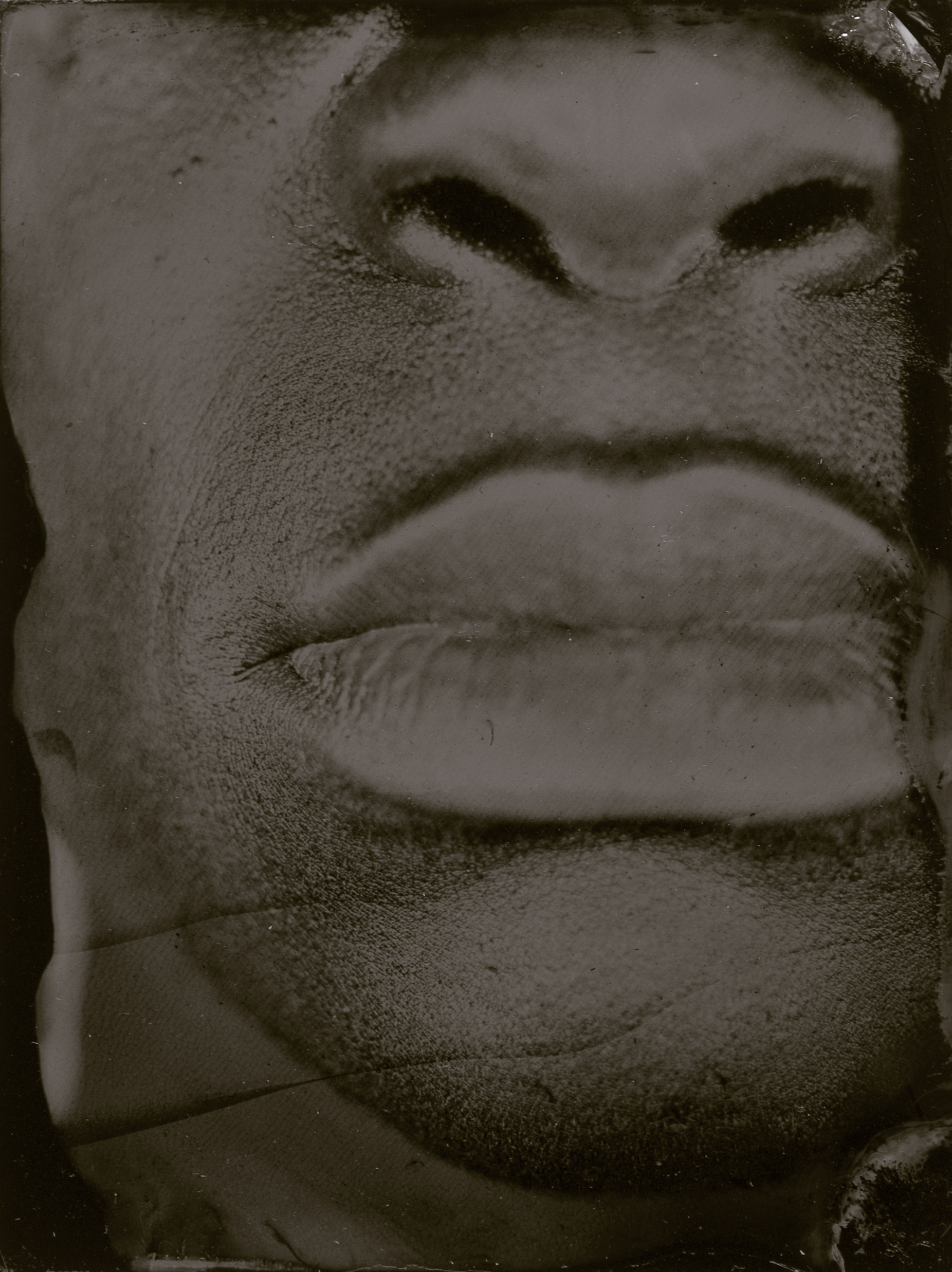

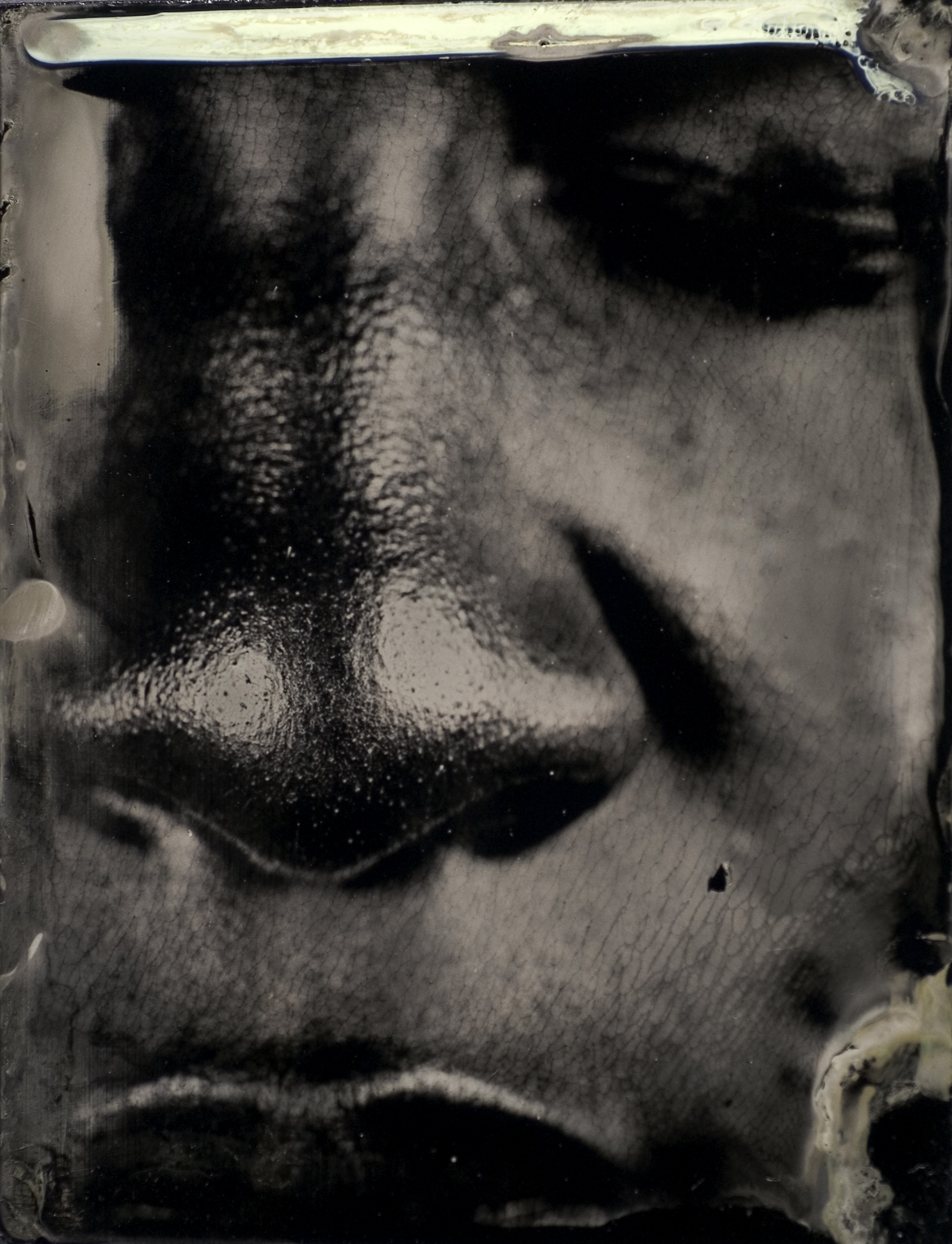

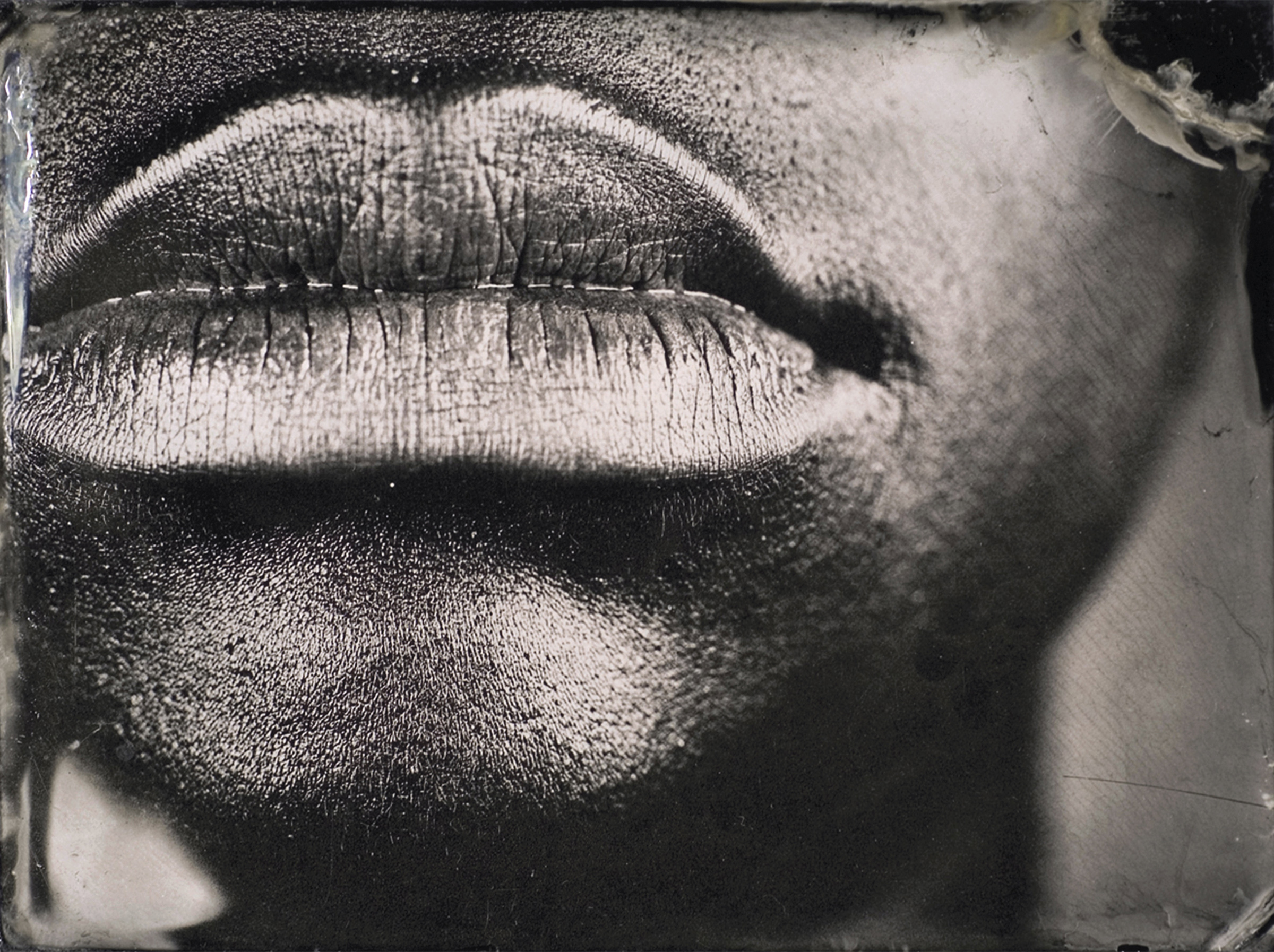

MG: Great question.. which may turn into a long answer… In the previous work Character Recognition – which is black glass ambrotypes – delved into the work of looking at cataloging by looking. After doing self-portraits that relied on categorical looking, and in projects previously, looking at my own body for years, I wondered if that was done with my own body. I wondered if we thought about the classification around the center- the norm. Does the norm see itself as a category? It has to be because I had been making work against that thing, that center, that normal for years.

The question of power is really one of imagining who is controlling the camera. Rarely do you imagine that on the other side of the lens is a black woman.

In terms of power, it is a dynamic relationship. My friends openly gave me control, because of our friendship and trusted me. And often when they saw the pictures, they recognized the image located itself somewhere between a stereotype and a portrait. This was actually the goal, to make these people universal descriptions of many categories. I don’t know if that is the way history plays with the portrait. Many historic photographers wanted to offer truths through portraits, here, I offer descriptions… which I think is something different. The issue becomes what the viewer has to question.

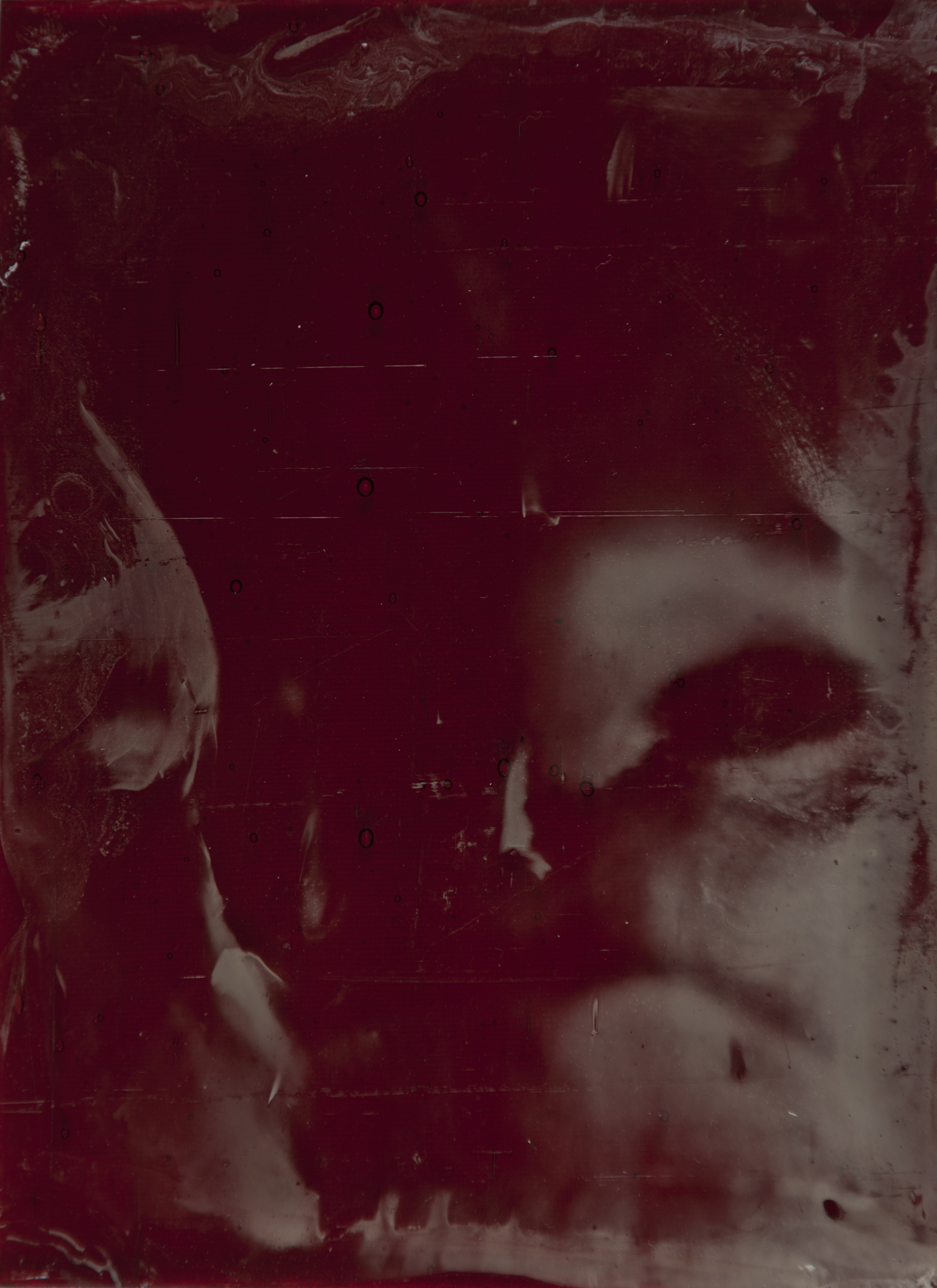

From the Series Undertones, Plate number 51, Ambrotype on stained glass, 4”x3”, 2018

ZJM: When thinking about the many power dynamics in photography/portraiture, are those things you think about before making work, when you’re in the midst of it, or after? Do you have those conversations with your students?

MG: Well I think about the relationship of being the image-maker, being in control of the gaze and the power that instills, from the start. There is a large amount of control that comes about in the composition and organization of the image, what is included or excluded in the environment that is in immediate conversation with the sitter. Students often are so focused on the subject, they often forget about the control they can instill. They are generous to think the image is only about the subject itself and forget that it also speaks to their intent and wishes. I talk to my students about acting as a director, suggesting things for the sitter to do and gestures… but also to walk around the sitter. It is nearly an impossible discussion because as the teacher, I am rarely around during the act of photographing. So we have to talk through that control only through the pictures once they were made. Often the questions revolve around why other images were not made, where can they be aggressive in imposing their thoughts. Many students think this is odd… but eventually they want to say more with their pictures, and therefore take up the challenge of exerting their control.

ZJM: In a 2012 interview with David Gonzalez of The New York Times, about My White Friends you say,

“My fear is that people will only see them as portraits and not as this bigger conversation because people won’t want to look at the whiteness. It’s not until you hear the title ‘My White Friends’ that the conversation begins.”

This is something that I often have anxiety about in my own work. I’m curious to know if this is still a fear that you grapple with, and how you work through it.

MG: I have learned that everyone looks with their own eye, and each eye is distinctive, born out of their own lived life and cultural context. Some eyes investigate, some only respond to beauty, some avoid confrontation, and others only want to see what they agree with. I can not transpose my way of looking – which is interested in dissecting and digesting all of the visual clues of the image, one clue is often race- but also place – and also function- onto others with only the photograph (and somehow how the photograph will always fail). In this case, titling was my workaround. In other work – leaving photography has been necessary to ask people to look differently.

I don’t consider it a fear anymore. It is just a fact. Some people will look at an image and will read always racial identity in a portrait all of the time, some will read “I” when it is not like them, and some will (claim) not to read it. I am more comfortable with all of those conversations and perspectives instead of claiming there is only one correct way to read an image.

ZJM: In my class’s first discussion, I brought in the example of Michelle Dizon and Việt Lê’s White Gaze. Are you familiar with the work? We spent a majority of our time picking apart the term exoticism. This led us into colonialism and desire: how colonial forces have a desire to own/objectify while also building institutions and/or knowledge that will, in turn, create a desire in those objectified to aspire to whiteness. Do you feel that the concepts of exoticism and desire play a role in your work? If so, how?

MG: I am not familiar with the book, but now about to be purchased in 3..2..1.. wait.. it is sold out.. dangit.

I do think outside of MWF there can be a fetishizing of an object, which could lead to the exoticism of the black body. I want that fetishizing to happen around the medium and process of photography, not the subject matter of the body.

From the Series Undertones, Plate number 26, Ambrotype on stained glass, 3”x4”, 2018

ZJM: You’re currently teaching at Spelman College. Was there a specific point in your career where you knew that being an educator was your calling? How do you define your practice as an educator?

MG: When I was at Wash U – I just had the thought that I could do this I could teach visual history, and do it better than the professors around me at the time. Now, to be honest, I was young and arrogant, but the thought was not around the techniques in the darkroom or lighting, but around facilitating larger conversations about the potentiality of photography and how someone could use it as an art form. So I was young and naïve…. Cause well, in order to do this, you have to teach people to understand and in fact master the technique, so those questions don’t become the forefront of the conversation.

I have thought about my teaching process a lot in the last years, especially now teaching at a historical black all female college. And I have asked myself a lot if the teaching technique has changed because of the population of students I have. I don’t think it has… My teaching process is this… getting students comfortable with the process, while asking them what is the big conversation they want to have with the world. What do they want everyone to know about, or think about? And then, can some form of photography or art help to facilitate that conversation. How can the medium help beyond just pointing at the issue, how can the medium help demonstrate your perspective or ideas?

I recognize this is a lofty goal. It takes more than one class… it also takes a lot of trust from the students as I am continually questioning their techniques and their ideas. But it often blossoms into an individual stance that is a new voice in the world.

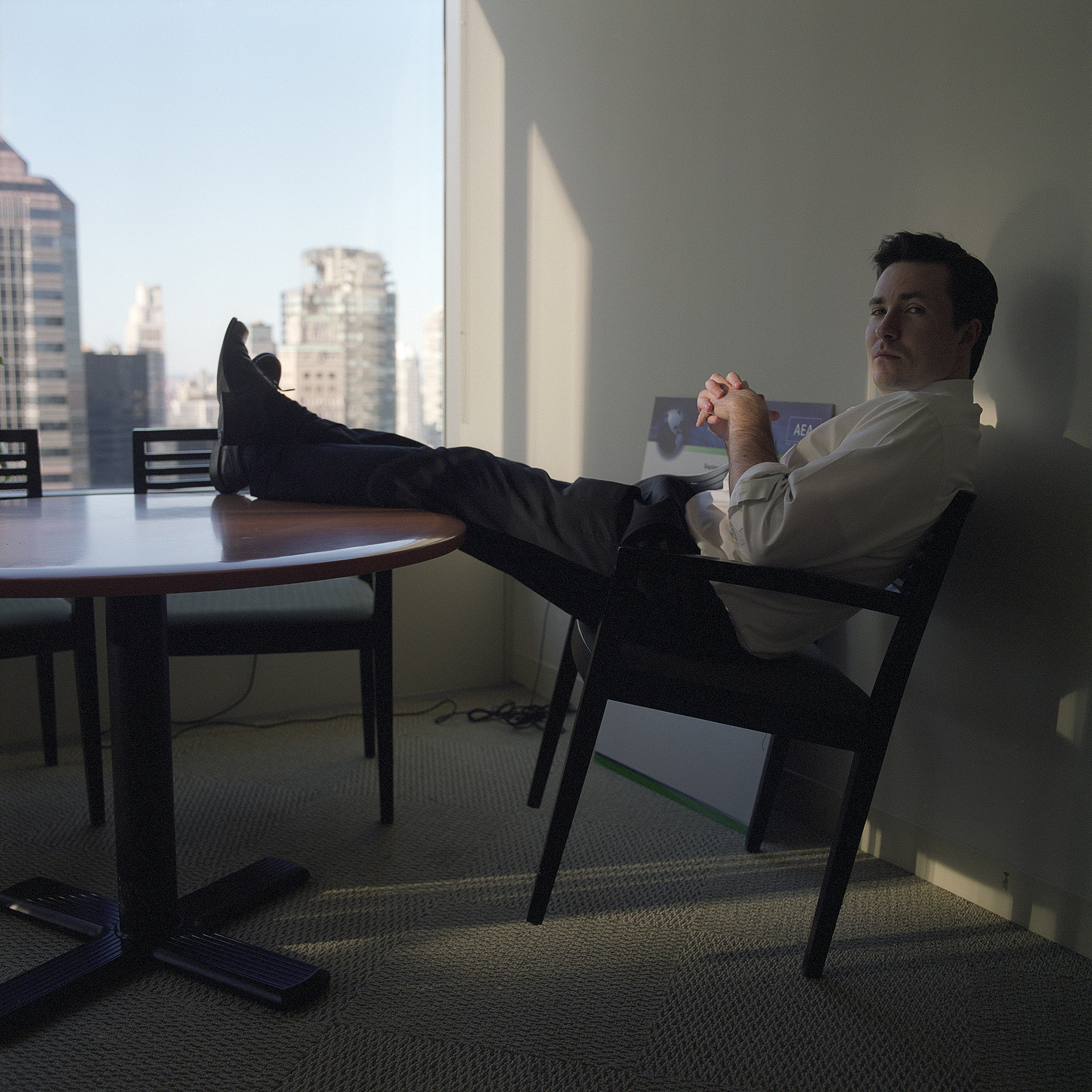

A.G., Rochester, New York, 20”x20”, Digital Print, 2007

ZJM: In my own limited experience as a professor, one of my primary concerns is trying to find ways to make my curriculum more equitable. This comes from the shortcomings I experienced in my own education, a specific example was taking a contemporary art history course. We got to the section titled, “Black Art”. The professor explained that they understood making a section focused solely on Black makers was short-sighted, but they still did it. How do you approach the process of trying to decolonize the classroom? Is it about incorporating intersectional thinking? Is it more than that?

MG: I wouldn’t use the world decolonizing.. but instead re-centering different thoughts. Even before I came to Spelman, at CCC I was mindful of making sure that in my upper-level courses that artist examples were as close to 50% female, and had always global perspective. If we educators only follow this history of photography, it often takes us through inventors and those who did it first. Well if we reposition that question to how did that invention affect a community, or who took an invention and tweaked its original meaning into something that reflects a cultural position, all of the sudden the list of artist who should be discussed shifts drastically.

In starting a program, writing the curriculum and then new classes for an HBC community, it is powerful and humbling to reconsider the canon and help students learn all/more different than I was taught. Teaching is a process of continual discovery, for both the students and me as we start to see a bigger world.

ZJM: It has been great speaking with you Myra, thank you so much for taking the time to share your work and words. Good luck at Spelman, I really look forward to seeing your impact on the program.

MG: Thank you, Zora. It has been fun to discuss this all with you. And developing the program at Spelman will be a fun adventure! Till Soon.

All images © Myra Greene