Q&A: Michelle Millar Fisher

By Jess T. Dugan | September 23, 2021

Michelle Millar Fisher is currently the Ronald C. and Anita L. Wornick Curator of Contemporary Decorative Arts at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Her work focuses on the intersections of people, power, and the material world. At the MFA, she is working on her next book, tentatively titled Craft Schools: Where We Make What We Inherit, and, as part of an independent team of collaborators, on a book (MIT Press 2021), exhibition, curriculum, and program series called Designing Motherhood: Things That Make and Break Our Births. Find it on Instagram at @designingmotherhood. The recipient of an MA and an M.Phil in Art History from the University of Glasgow, Scotland, she received an M.Phil from and is currently completing her doctorate in art history at The Graduate Center at the City University of New York (CUNY).

Michelle Millar Fisher, photo by Brigitte Lacombe

Jess T. Dugan: Hello Michelle! Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me today. I’m so excited to jump in and talk about all of the different and exciting aspects of your practice and career, but to begin, could you tell me a bit about your path to getting to where you are today as a curator and historian?

Michelle Millar Fisher: Thank you for having me! And thanks for the great questions. It’s been a very circuitous path to becoming a curator and historian and I still don’t feel like I’ve “arrived.” My path to what I do today was affected really early on by two factors. The first was growing up in a country, Scotland, where higher education is free for everybody. That’s not to say that there weren’t asymmetries and inequities in the system, because they were, and there still are, but it is a landscape that’s light years ahead of the US model (Scotland also has awesome models for universal literacy, and the Finnish-inspired baby box, and free period products, and universal healthcare ...). I’m the first person in my family to get past high school, and so being able to have a university education and not have significant student debt equipped me to consider a different range of opportunities than had been afforded my mum or my grandmother.

I took all the sciences in high school because I thought I wanted to be a veterinarian. I came from a single-parent family, and I had jobs that contributed to our domestic bills from early on. As a teenager, I was looking for something vocational that I knew might offer a stable income and was legible to me as a “career.” I grew up in a very rural area and veterinarians were a respected part of the community. I did work experience with a few of them, and worked on a dairy farm. I had my own animals, including a small flock of sheep. However, while I was OK at sciences, I excelled at writing and communication. The thing I love to do most in the world, and still love most, is reading. In my leaving exams, according to my high school deputy principal, I got the highest marks in the country in my English exam. So off I went to Glasgow University to study English and Scottish literature. That’s where the other part of my journey to what I do today was put into place. I defected to the visual arts when I met a really significant mentor there, the design historian Juliet Kinchin. She introduced me to the history of architecture and design, which I loved because I could see how it had such an immediate impact on our daily lives. She was the person from whom I found out that graduate school existed, and she showed me how I could apply for it and she helped me get an academic scholarship to pursue it. And she has written me more recommendation letters than I can remember. She has been a similar mentor to countless other people. To say that I owe her a great deal is a huge understatement.

I didn’t know what a curator was until much later, though. During college, my main source of income was as a cook. I’d work all weekend and mornings and nights at the North Star deli in the Maryhill neighborhood of Glasgow, and go to lectures during the day. I had really great cooking and baking skills by the time I was in my final year of university, but I didn’t have any art experience. I went to the University Museum and the only paid job there was as a security officer, so that was my first job in the arts. My second job came when one of my university instructors, Tina Fiske, asked if I’d like to be an artist assistant to her husband, who turned out to be the British sculptor Andy Goldsworthy. I don’t know if I was that helpful, but it was my first experience working with a living artist, and it was fantastic. Andy’s a really kind, thoughtful, ethical person, and so is Tina. I could have had such a different introduction to the art world and I am so grateful that instead it was with them—they set a standard for kindness and rigor about their work, as did Juliet.

The following year, I saved up and I applied to about fifteen different internships on the East Coast of the US. I got rejected from all of them, and then the Guggenheim emailed me a few weeks before the summer of 2005 because somebody had dropped out and I was their second (or maybe third!) choice, and that’s how I got my first experience in a US museum. I’d never been to New York before. I stayed at the YMCA on Lexington and 92nd and I fell in love with the city in under two hours. Who wouldn’t? At the end of the summer, I asked them for a job and for a visa. I’m part of a generation that had a sweet spot for employment during what has otherwise been a bit of a shitshow—I was far enough after 9/11 that the hiring freezes had been lifted, but Lehman Brothers hadn’t yet crashed. So I was at the Guggenheim for four years in the education department and I loved it.

That’s where I found out about curators. I realized that, for better and often for worse, at the time, curators were the decision makers in museums, and I wanted to make decisions about what I did. And so began a really long process of applying for a PhD, applying to jobs tangentially related to the curatorial field, and gradually building up a portfolio of writing, research, and exhibitions. My first real curatorial job in a museum came in 2014 at MoMA in the architecture and design department. I had applied four times over a period of six years. I finally made it in. And while it was hard work, I finally felt like I had found my mother tongue. My mentor there was the incredible contemporary design curator, Paola Antonelli.

I Will What I Want: Women, Design, and Empowerment

JTD: Wow, that’s wonderful. I love hearing more about your circuitous path. Much of your work focuses on the intersection of gender and design. In 2018, you worked on a co-organized exhibition and co-published book, I Will What I Want: Women, Design, and Empowerment, in conjunction with muca-Roma, Mexico City. Could you tell me more about this project, including your process for working on it and the response once it was out in the world?

MMF: Absolutely. The first thing that should be said about that project was that it was a total collaboration between myself and a really fantastic colleague based in Mexico City, the design curator Jimena Acosta Romero. I was interested in this material when I worked at MoMA but it was immediately clear that it wasn’t going to have an audience there. The design and architecture field is dominated by men, and men who have little interest in issues of gender, or design for birth, lactation, abortion, and other similar experiences that are relevant to a wide spectrum of people but are often seen as taboo or beneath scholarly and public consideration. Paola encouraged me to keep pursuing this interest even if it wasn’t going to be part of my work during the day, and she introduced me to Jimena, whom she’d met when she lectured to Jimena’s class (she studied in the Bard curatorial studies program). Paola knew we had similar interests. That was back in 2015. I was teaching in the evenings at Parsons at the time, and they have design galleries that students and faculty can apply to use. So Jimena and I applied together, and put up an exhibition, I Will What I Want, and created a book on a shoestring budget in 2017. It traveled to Mexico City in 2018. It was a really wonderful teaching tool, and elicited many great conversations with students, especially about how our social, geographic, and economic locations determine our experiences around reproductive freedom and health and justice. But this was still before the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements became truly public, even though marginalized people had been speaking up for decades (and centuries!) before. The exhibition was in a gallery that had windows right on Fifth Ave in Manhattan, at 13th Street. I think if the exhibition was there today, it might have had a little more attention and engagement than it did in the end. But it is a project I am so glad to have done, and done with someone as talented as Jimena. Researching it early in my curatorial career, and having to do so outside of the institution for which I worked because it was not interesting to them, set me on the path I am still on today.

I Will What I Want: Women, Design, and Empowerment

JTD: You recently published a new book (congratulations!) with the MIT Press titled Designing Motherhood: Things That Make and Break Our Births. This book is part of a larger project that includes an exhibition, curriculum, and program series. Could you tell me more about this specific project and what motivated you to work on it? And, could you also expand on your thinking around creating projects with so many different elements?

MMF: It really feels exciting to talk about the Designing Motherhood project now because it’s been so many years in the making, and I am so grateful that it’s out in the world. Like all of the projects I have mentioned above, and indeed all the work that I participate in, this project is also deeply collaborative. It began with a meeting, at a baby shower I hosted for a friend at my house, with my writing partner and ride-or-die, Amber Winick, who is also a design historian really interested in designs related to human reproduction.

It is in some part an expansion of the project Jimena and I did, but it also encompasses many, many elements that are totally new. The project really came out of not seeing the design systems and objects that we really cared about, everything from at home abortion kits to menstrual cups to cesarean section curtains to family leave, to postpartum mesh underwear, fertility medications, and antinatalist graphic design, and many other equally fascinating designs not being given due attention in design history scholarship, museum exhibitions, and collections, and just in public, to be very honest. That’s changing a bit now. When we started the project it was at a moment in time when many others were also trying to, in their own spaces, have similar conversations in the visual and literary realm. People like Maggie Nelson, Heji Shin, Jessica Friedman. The New York Times developed a parenting section in 2019. And there has been a lot of activism on Instagram across many intersections of reproductive justice. All of this work, of course, builds on activists from the past century, many of whom have been women and non-binary people of color.

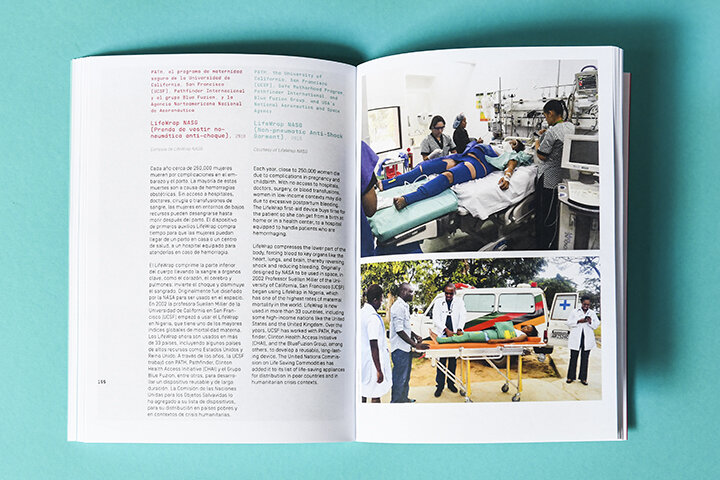

Image spread from Designing Motherhood: Things That Make and Break Our Births (MIT Press, release date September 14, 2021). Photo: Erik Gould. Image courtesy Designing Motherhood.

I again tried to get support from any institution at which I worked or had worked in the past, and it was a closed door. So Amber and I partnered with an amazing organization called Maternity Care Coalition that has, for the past 40 years, been working locally in Philadelphia to support maternal and infant health. I think people know statistics a lot better now than they did a few years ago, but birthing people have had declining health outcomes in this country for the last three decades even though the US spends more per capita on healthcare than any other developed nation. Statistics get even worse if you are a birthing person of color when maternal mortality and complications skyrocket. So it’s not only an interesting conversation but a deeply necessary conversation to have in major cultural institutions, be it a museum or newspaper or on the radio.

Thinking about it as a polyvocal and multi part project comes out of my training with Paola where she was very clear about the role of public conversation at every stage of the research process. But the many parts of this project have also been shaped by the amazing team who have worked on it and really made it what it is. Gabriella Nelson is a city planner and also the associate director of policy at MCC, and she brings a very specific lens as a design expert but also a Black mom who is raising a Black son in a society that does not care in humane ways for Black men. Zoe Greggs is the Curatorial Assistant on the project and an artist, and she brings an incredibly intuitive and thoughtful lens to the conversations that we have around race and gender, as does Dr. Juliana Rowen Boston, a design historian who has a specialization in race, domesticity, and design. And then we have many, many contributors to the book, and the public programs. We always say that this project is universal in that everybody alive today has been born, so everybody has a stake in the designs that shape us from birth onwards, but that each birth is completely unique, too, so everyone’s experience matters in understanding these designs holistically.

We struggled a bit with using the term motherhood as it tends to imply a binary, but we also contend that it’s a shorthand for acts that go beyond a gender binary and beyond people who’ve been pregnant or giving birth. I don’t have children. I think it’s a description that can be embodied, deferred, refused, taken on as a duty or expectation, or otherwise engaged with, in all of its knotty contours. Motherhood is myriad.

Fisher-Price Nursery Monitor, 1983. Photo: Erik Gould. Image courtesy Designing Motherhood.

JTD: As your previous answer makes very clear, much of your work is socially and politically engaged, and the work you’ve done has taken many forms and existed in different kinds of social and cultural spaces, both within and outside of museums. You are currently the Ronald C. and Anita L. Wornick Curator of Contemporary Decorative Arts at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, a rather official kind of institution, if you will. What are your thoughts on the intersections of art, curatorial work, and activism? How do you negotiate working within the institutional space while remaining engaged with, and responsive to, very current social and political ideas or concerns?

MMF: We cannot divorce the political from our everyday professional practices. A few years ago I had an uncomfortable phone call with a senior curator who told me that they know me more for what they termed “my activism” at the intersection of art and labor than for my curatorial work. I could tell that it definitely wasn’t a compliment. My first reaction was to smile. Of course they do, I thought. I work on contemporary design, the outcast of art museums. My awakening to the issues and ideas about which I (and many others before me, and with me now) have been active, including valuing human labor and feminist approaches to the worlds around us, did not come in the hours outside of work, but actually very deeply within the act of making exhibitions and public programs and publications. In the formulation of this curator, acknowledging the political context of labor in the arts and doing curatorial work were two separate things. But of course, they’re not.

We all know that material culture is never divorced from its context, and context is never neutral, and so the choices we make and the actions we take, the social locations we occupy, and the objects or projects that result each day from them have an inherent politics. I believe that ethos is the umbrella for everything else that we do. In framing our daily working lives in craft as a space of ethical and political potential, I am inspired by the contemporary British archaeologist Alexander Langlands who, in his odyssey to adumbrate the edges of craft as a term and a practice, writes of medieval English King Alfred the Great. The ninth century king used the term craeft to denote his own project of building the foundations of the modern English state (Langlands notes that it appears over 1,300 times in Anglo-Saxon documents). To Alfred, craeft did not mean a singular skill, nor did it denote an aesthetic, or field, or type of medium-specific object as it might today; it denoted, as historian Peter Clemoes writes, “the organizing principle of the individual’s capacity to follow a moral and mental life.”

Increasingly, I think that the best kinds of work towards equity happen outside institutions, in the pastoral relationships and care relationships that we have with our colleagues. Those often fall in the interstitial spaces of our work lives, or actually happen outside of institutions entirely. I’m thinking, for example, of the salary transparency spreadsheet which occurred when a group of co-workers, myself included, shared our salaries when someone needed to come up with a range to put on the cover letter of a job application. Our connection was through our workplace institution, but the real work happened outside of it.

I have not yet been in an institution that nurtures its workers in ways that truly supports equity or authentically responds to current issues. I don’t think large, historically white-dominant museum institutions (which does not account for all museum institutions by any means) are set up to offer the radical change that they often articulate in their mission statements. I know that equity doesn’t happen when there is a superficial public program or well-intentioned conference, usually instigated by curators, on urgent topics. And so I negotiate working within institutional spaces by trying to remain at a comfortable distance from people who are inured to or, worse, actively creating resistance to change. There are some fairly easy places and things to avoid, like art fairs, openings, and public programs that go viral before they even take place.

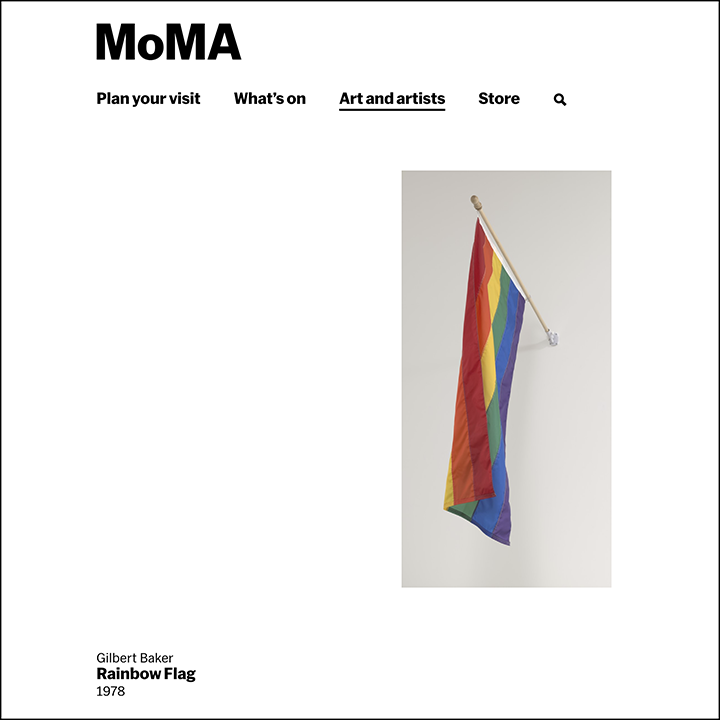

JTD: When you were at MoMA, you acquired the rainbow flag for the permanent collection. I’m interested in the idea of acquiring an object such as this, which is so deeply embedded in cultural and social movements, within an art museum. Can you tell me about your thinking behind this? What role does it play in the collection? How has it been used in exhibition or scholarship?

MMF: That acquisition had a very specific context. About five years prior, in 2010, Paola had acquired the @ symbol, an act that really highlighted both the history of digital communication design and the legacy of the notion of the “humble masterpiece” at MoMA. In 2004 she had created an exhibition of that very name at MoMA—the premise was that we are surrounded every day by designs that have a profound effect on our lives but that we don’t really consider too closely, and we perhaps should. She looked at things like the white T-shirt, the Bic pen, the Chupa Chup lollipop, and the self-aligning ball bearing. She was referring to an inheritance from the very earliest design exhibitions at MoMA that looked at machine parts like airplane propellers and springs as well as scientific glass beakers, and elevated them to the status of objects worthy of consideration and collection.

So my proposal for the Rainbow Flag came out of Paola‘s acquisition of the @ sign. We were looking at other symbols and icons in order to make an exhibition that showed many of them, and so we “acquired” other things like the on/off power button icon, the Creative Commons symbols, and the recycling logo. These are design histories that I really loved diving into and bringing into a collection like MoMA’s, and they also pushed at the boundary of what “collecting” was as well as what constituted design. The rainbow flag was a similarly powerful icon and one of its creators, Gilbert Baker, lived in New York so that was a simple phone call to him to ask if we might be able to add it to the collection.

Like any symbol, it has been remixed and reused, and different iterations have been created. I think that’s the beauty of something like the Rainbow Flag or the recycling logo, both of which were never trademarked, and were deliberately made available to everyone because the creators believed that their power should be democratically accessible.

It was first put on exhibition at the end of June 2015. We had just acquired it into the permanent collection in the first week of June after months of preparation, like we do with every acquisition, for the committee meeting in which it would be presented. And then the news of the Supreme Court decision legalizing same-sex marriage across all states came down. We bought a flagpole from a local hardware shop, and with preparator colleagues we mounted it in the design galleries at MoMA. A small crowd of staff and visitors gathered around to watch it happen, and they were hoots and cheers and some tears. It was really beautiful. I often wonder what exhibitions can achieve in the wider world, but that was a moment that very directly spoke to folks seeing their identity and their experiences validated in a public setting. And it was powerful.

JTD: You are currently planning a fairly massive undertaking to research and write about contemporary craft throughout the United States. My understanding is that it will involve five cross-country Amtrak trips and meetings with potentially hundreds of artists, culminating in a book and exhibition. Can you tell me more about this project and what it will entail?

MMF: Over the next year, I am going to visit every state in the United States to visit with people in their studios, schools, and homes (if they will have me). I want to learn more about their relationship to craft and how it has been shaped by an important teacher. I will ask artists, curators, educators, and community members: Who was your most important craft teacher?

That teacher might be their grandmother or it might be someone in an accredited school or it might be a neighbor. Or, they may have a story that they really lacked a teacher and so have become the mentor or teacher they wished they'd had. All stories are welcome.

The project is called Craft Schools: Where We Make What We Inherit and it's supported by the Center for Craft in Asheville, North Carolina. The title gestures to the notion of a school of thought, an intellectual or philosophical tradition which can come to define a field, and an inheritance ripe for expansive rethinking and intentional reconsideration of its boundaries. The subtitle is a deliberate provocation—an invitation to interrogate many different places of craft education, the plural identities formed within them (the “we”), and thus the multiple and often contested inheritances of these sites, especially those unacknowledged in craft canons.

As sociologist Richard Sennett writes in his 2008 book, The Craftsman, craft is an ethos rather than a specific movement, history, set of aesthetics, techniques, or materials. It is an approach to being human, and is found in all walks of life where someone does something with care, attention, and a moral compass. For Sennett, community organizing is craft. Computer programming can be craft. Parenting is a craft. Craft is, in essence, a way of meeting the human, plant, animal, or mineral worlds around us from a place of radical care. Many artists express this approach to the world through the works and relationships they nurture into being.

I’m excited to find out from folks across the country what craft means to them, how they came to their knowledge, and to bring some of it back to resonate with the contemporary craft collection and the visitors at the MFA. It might end up as a book and an exhibition, but the primary goal is to leave the museum and to go to meet people in their own spaces. COVID has made planning for books and exhibitions much harder in an institution, but what I do have, thanks to the Wornicks who endowed my position, are funds that I can put in the hands of great living craft artists by acquiring their work.

I’m following in the footsteps of many who have gone before me. Writers and travelers, of course, but the places I will go have been traversed in migrations and movements long before me, and I acknowledge that not all journeys have been easy or even chosen. I am conscious that I am able to choose to travel. I am going by train to leave the lightest footprint possible and my main goal is to listen really carefully and intentionally to the artists I meet. Everyone I have made appointments with identifies with craft in ways that are very far outside the studio craft canon that constitutes the majority of the MFA’s craft collection.

JTD: When we spoke recently, you used the phrase “culturally appropriate oral history” in reference to the ethics you follow when meeting with artists and conducting your research. I’m so interested to hear more of your thinking around this idea. Could you expand on what you mean when you say that, and share your thoughts on oral history more broadly?

MMF: A lot of what I do, the same as many curators, is listen and learn through asking questions that deepen an inquiry into somebody’s practice. That’s often an artist during a studio visit, but it’s also many other people from different walks of life. I did many oral history interviews, for example, for the Designing Motherhood book. I talked to scholars and subject-area experts, but I also spoke to people who had direct experiences of the design objects and systems that we were looking at: folks who had been affected at birth by thalidomide, for example, and then went on to give birth to their own children; men who had given birth, and live through fairly hostile medical and social environments; or people who had tried to design something better when they had a bad experience with it. In every case, I’m always so aware that I’m listening to somebody’s story and while I can empathize and be human, I can never fully understand the extent of their experience. So a culturally-appropriate approach is one that understands the limits of my own experience and honors the specificity of the storyteller’s, as well as one that is non-extractive.

In a keynote talk I gave a few years ago for CraftNOW in Philly, which now feels like it happened a decade ago in another world, I spoke about crafting a moral compass. I was speaking to a craft-oriented audience, and I was also newly employed as a curator looking after a craft-centered collection. I laid out the argument that craft is an ethos as much as a circumscribed set of skills or an aesthetic description of certain material outputs. Craft is often framed as working very directly, tangibly, done by getting hands dirty, something that you do from start to finish with your own hands and mind. Perhaps this is the most essential definition, that craft is something that can only be done by you. I liked this description enough to want to expand it to the work I might do as a curator of craft.

I can’t think of a more apt way to describe one’s moral compass than the idea of getting one’s own hands dirty. No one else can live—can fully embody—ethics but the individuals or collectives pursuing them. You have to be in it to be truly connected, doing the work, figuring it out. There’s no outsourcing. You have to learn the skill, fumble with it, practice it, be humbled in the process, and keep reaching. If understood in this way, then I would argue—as others before me, including Sennett—that creating an ethics for being and knowing and doing in the world is perhaps the ultimate craft.

For me, the notion of “crafting a moral compass”—of finding an ethics to my daily work—means working sustainably with craft makers, designers, public audiences, colleagues, and collectors in service of creating a climate where craft and design remain relevant, cared for and about, and where stories reflective of many communities and experiences are told through the lens of material culture. I think it’s a view most colleagues find overlapping if not synonymous with their practices within the field of craft, whatever form they may take. And a lot of that work starts with listening to people’s stories, honoring them, and letting them ring out in the places where the storytellers want them to be heard.

JTD: I suspect we may have covered everything, but is there anything else you’re currently working on, or thinking about, that you’d like to share?

MMF: I think we covered it! :) Thank you again for having me!

JTD: Wonderful, thank you so much Michelle!