Q&A: Melanie Walker

By Hamidah Glasgow | October 20, 2022

Melanie Walker is a mixed media artist invested in ideas. She has exhibited her work both nationally and internationally and has work in more than 200 permanent collections including the Smithsonian, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson. Her approach to materials includes photographic media, alternative processes, digital art, sculpture, installation, fiber art, printmaking, costume design and public art. She has received numerous grants and fellowships including a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, Colorado Council on the Arts Fellowship, Polaroid Materials Grants and an Aaron Siskind Award.

Hamidah Glasgow: How did your life in art begin?

Melanie Walker: I think my art life began at birth. I grew up in an art household surrounded by walls covered with art and a steady stream of artists always coming through the house, many of whom were considered some of the more important 20th-century photographic artists. I remember being shocked at age five that not everyone's father made pictures.

I also think that my earliest memory has been instrumental in my art life. I was born legally blind in one eye and had to undergo two major eye surgeries at 3 and 31/2. I remember waking up alone, strapped in a hospital bed with an eye patch over one eye. I looked down the hallway to see a chimpanzee riding toward me wearing a band leader's uniform. I made a piece about this years later and was in an exhibition in LA with a woman who was a painter who had the same surgery at the same hospital the same year for the same problem, and her father remembered the chimpanzee.

HG: You've spent the better part of 50 years as an artist and teacher. Your work is photo-based but encompasses many other mediums and approaches. I'm impressed with your imagination and expanse of work. Tell me specifically how you got into making art kites.

MW: Growing up around the artists that were many of my father's colleagues, I was greatly influenced by the experimentation and malleability of the work being made with photography in Southern California in the '60s. It seemed like there were no boundaries, and everything was possible. I have always been interested in questioning what constitutes a photograph and pushing against definitions. Being surrounded by pictures and conversations about pictures constantly led me to immersive installations. Being visually impaired pushed me further into the idea of multisensory experiential photographic installations with tactility and sound.

The kites evolved from attending international kite festivals and watching the audience. I think it was the festival in Thailand where we had an audience of 500,000 in one weekend. That pushed me to make my endangered species project into flying objects. Raising issues into the sky seemed almost automatically to draw a crowd. Plus, I have always felt like an outsider, and flying kites is about as outside as a person can get…

HG: How is your work informed by your limitations of vision? It's interesting how so many photographers have vision issues. Perhaps, exploring one's physicality as it relates to vision leads to photography in a way.

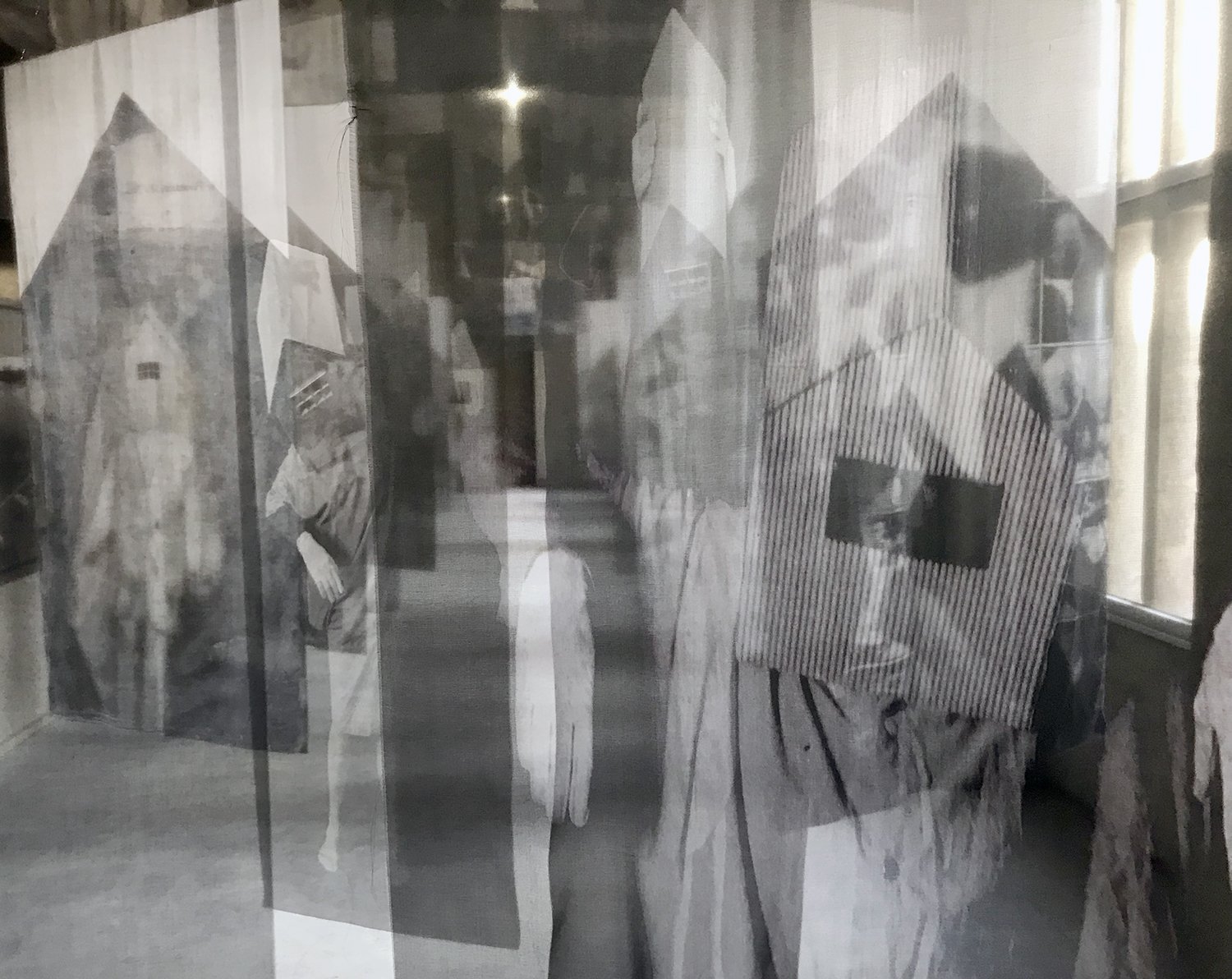

MW: I don't know if it has. My vision has always been the way it has been since birth, so I've never felt limitations or known anything different. If anything, I feel drawn to the camera that is also a cyclops or a one-eyed monster. In my installation work, I have attempted to convey how I experience the world with my double vision challenges that have gotten to be a bit more of a challenge as I have gotten older. I use a lot of transparent materials in an attempt to convey the multiple visual input I experience. I have always tried to be a bridge to empathy through my work as a means for others to see in a different way.

HG: Working with your father's legacy has been a long-time project for you. Where does that stand, and how do you see moving forward?

MW: It is ongoing, and I don't see an end in sight, to be honest. I have been placing his work in a number of collections, and the bulk of his archive will be housed at the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona in Tucson, where he was a professor. He was my primary influence and my best friend and significantly impacted my life in the arts.

He worked for 60 years and was such a pioneer, constantly moving the vocabulary of photography forward. He was self-taught and had success in his advertising work. He walked away from it in his 50s and dedicated himself to his work. There was little audience for photography as an art form in the '60s and '70s, and he wasn't interested in the promotion that seems to go hand in hand with what we see as 'the art world. Todd Walker was considered a photographer's photographer, and AD Coleman once credited him for establishing an atmosphere of openness in photography. Where experimentation and all approaches were legitimate and where photography is merged with whatever can be imagined.

There are artist books from the 60s–90s, some including his early digital works (1981-98) before the internet. He worked with the press as his art medium in tandem with photography and was interested in the politics of making art available to everyone. On the wall: FREEDOM OF THE PRESS BELONGS TO THE PERSON WHO OWNS THE PRESS…he fully believed and practiced the democratization of the arts…so many editions of beautiful prints…

It's overwhelming…and a big part of my life's work.

Some of my recent work uses his damaged and deteriorating negatives from his early work for hire that he had to do to pay the bills. The decay for me becomes another layer of questioning societal norms…questioning the acquisition of stuff…questioning the American Dream….all of those images were made to sell something and lead us to where we are as humans on this challenged planet…and it's a way for me to continue to converse with my father about images, crazy as that may sound…

Collaboration - Todd and Melanie Walker

HG: How has the art world changed according to your experience, especially from the perspective of an older woman? Are things better now than they used to be, or do you still see many of the same problems?

MW: I think growing up with the art and political influences I was around, art has been a way to process the world. As a half-blind person, I have always used photography to understand the world; some have called me a visual satirist. I also feel like a cultural spy, like Kobo Abe's The Box Man, who lives inside a box (camera-chamber-room, surveillance, etc.), witnessing as an outsider. I think it comes from being differently abled…I don't like the word disabled…

But maybe that sense of being an outsider comes from being a woman in what was a primarily male-dominated medium. There were just a handful of women working with technology when I was in college. I was the only female in my grad photography program at FSU in the early 70s. I worked with soft photo sculpture with fabric and received very little feedback.

For me, nothing much has changed. I still feel marginalized, like a weirdo, an outsider, and invisible, but it has given me so much freedom...maybe it's my blindness, being a woman, or being shy…who knows. I have watched many of my female peers have successes, ebbs, and flows in their careers depending on the political climate. I don't think change is a linear thing. We are currently in a backslide moment regarding women in the arts and the world. Things seem to spiral, like one step forward, two steps back…The 'art world' is a vague entity that can be defined in many ways. It seems like it's connected to celebrity. I have the most respect for the unnamed artist who did what they did because they had to do it. Anonymous has always been the most prolific artist…I have always been drawn to folk art and the work of outsiders…

HG: What is your favorite project to date?

MW: My favorite is the one brewing in my head that has yet to come into the world like the garden was never so good as it will be next year. I see flaws with every project, but I think the Nomadic Dreamer installation in Portugal was one of the projects that came closest to realizing my concept.

HG: What is your dream project to do in the future?

MW: I guess I dream about doing an immersive interweaving of all of these seemingly disparate installation projects. I think climate anxiety has always been at the heart of my work in everything I have done. Ghost Forest came from grief over the forests being lost to fire, beetles, logging, and other factors. The Sheltering Sky was made in response to the air that all living things share. The Househeads and Nomadic Dreamer are connected to issues related to overpopulation, over-development, and over-use of resources.

HG: What would you tell your younger artist self?

MW: There's no correct answer, so relax and don't worry about what you think people are thinking about what you're doing because it's more than likely that they are worried about what people are thinking about what they are doing.

HG: How did you come to work in so many non-traditional ways? What did that path look like?

MW: I think it is related to all the experimental work I saw while living at home. During the 60s and 70s, before there was a market for photography, everything was very open, with a lot of experimentation happening. I also think the work included in the Photography Into Sculpture exhibition at MOMA in NYC inspired me. Also, when I was living in San Francisco after grad school, I spent a lot of my time with people doing installation work, sound art, and work that didn't belong to a defined genre.

HG: Please tell me and our audience a bit about your checkerboard house.

MW: After my eye surgeries when I was about 4, I had to do eye exercises to get my eyes to work together. One exercise involved staring at two checkerboard images and getting them to merge into one image. It never worked. I always saw two disparate images that never merged. I guess that challenge and that failure is still deeply embedded because that checkered patterning has appeared repeatedly throughout my work.

The checkerboard house was also a pragmatic decision when we discovered how much it would cost to remove asbestos tiles on the house. Painting was a much more affordable decision...

HG: Thank you for your time and insights.

MW: Thank you!

All images © Melanie Walker