Q&A: luis corzo

By Jess T. Dugan | June 23, 2022

Luis Corzo [he/him] (b. 1990, Guatemala City, Guatemala) is a Brooklyn based multidisciplinary artist. He received his BFA in Photography and Contemporary Creation at IDEP, Barcelona in 2012. He primarily works using the different disciplines of photography, but also works with video to explore the obscurities of human activity and the space in which we inhabit. His work has been exhibited in New York, Buenos Aires, Barcelona, Bilbao, Hiroshima, Sydney and Guatemala City, among others.

This interview is in collaboration with CENTER and is part of a series featuring the winners of the 2022 Social Award, juried by Jess T. Dugan.

Jess T. Dugan: Hello Luis! Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me today. I’m excited to speak with you in depth about your project Pasaco, 1996, but before we jump in, could you tell me about your background? What was your path to discovering photography, and how did you get to where you are today?

Luis Corzo: Yes, of course! Well, ever since I was very young, I have been interested in the arts one way or another. Specifically in photography, my earliest memories were that of my father, whose hobby was photography. On every family trip, he would bring his big case of cameras, lenses, and film and he would take thousands of pictures of us and the things we saw. My first memory of me taking a photograph was in 1997, a year after the kidnapping, on my first trip to New York. We were at the World Trade Center and I asked my dad for his camera. I meticulously looked for the precise center point of the middle of the Twin Towers; I laid down, looked up at them through the viewfinder of his Canon AE-1 and snapped a picture. As the years passed, I developed an obsession with camcorders. I would constantly steal the family camcorder, press all of the buttons and try to understand everything about it. Some camcorders had an option to take a snapshot and I frequently used it. Time passed and I got my first job at a Subway restaurant when I was 15. With the first paychecks I bought myself a Nikon D50 without having any idea of how to use it. I applied the same method as before and would just press every button and learned how to use the camera in that manner. I also remember that my favorite times were going back to Guatemala to visit family and documenting what I would see. The strange interzone between culture shock and familiarity amused me. In 2008, I dropped out of high school and moved to Barcelona to study photography and then decided to move to New York to pursue my photography career.

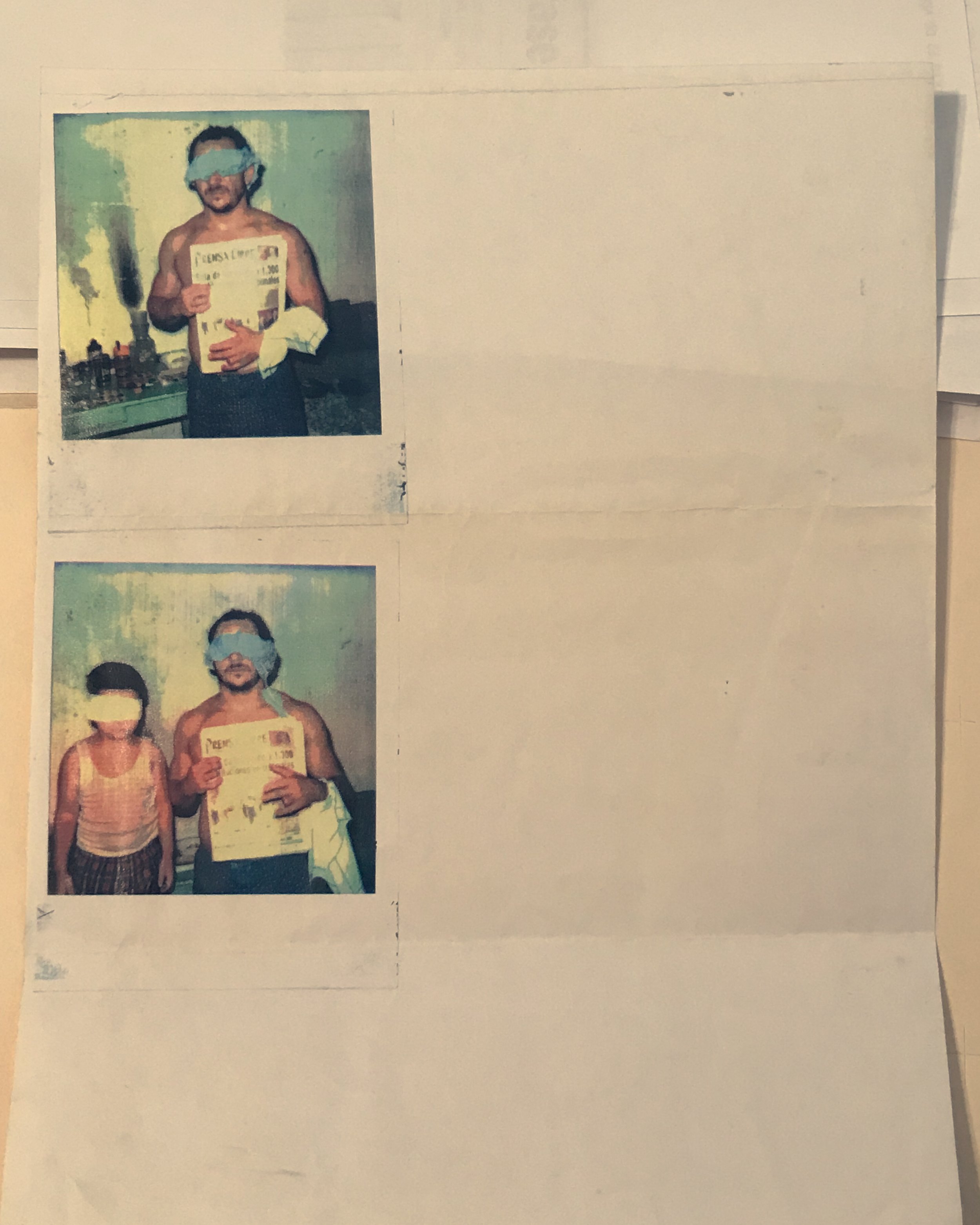

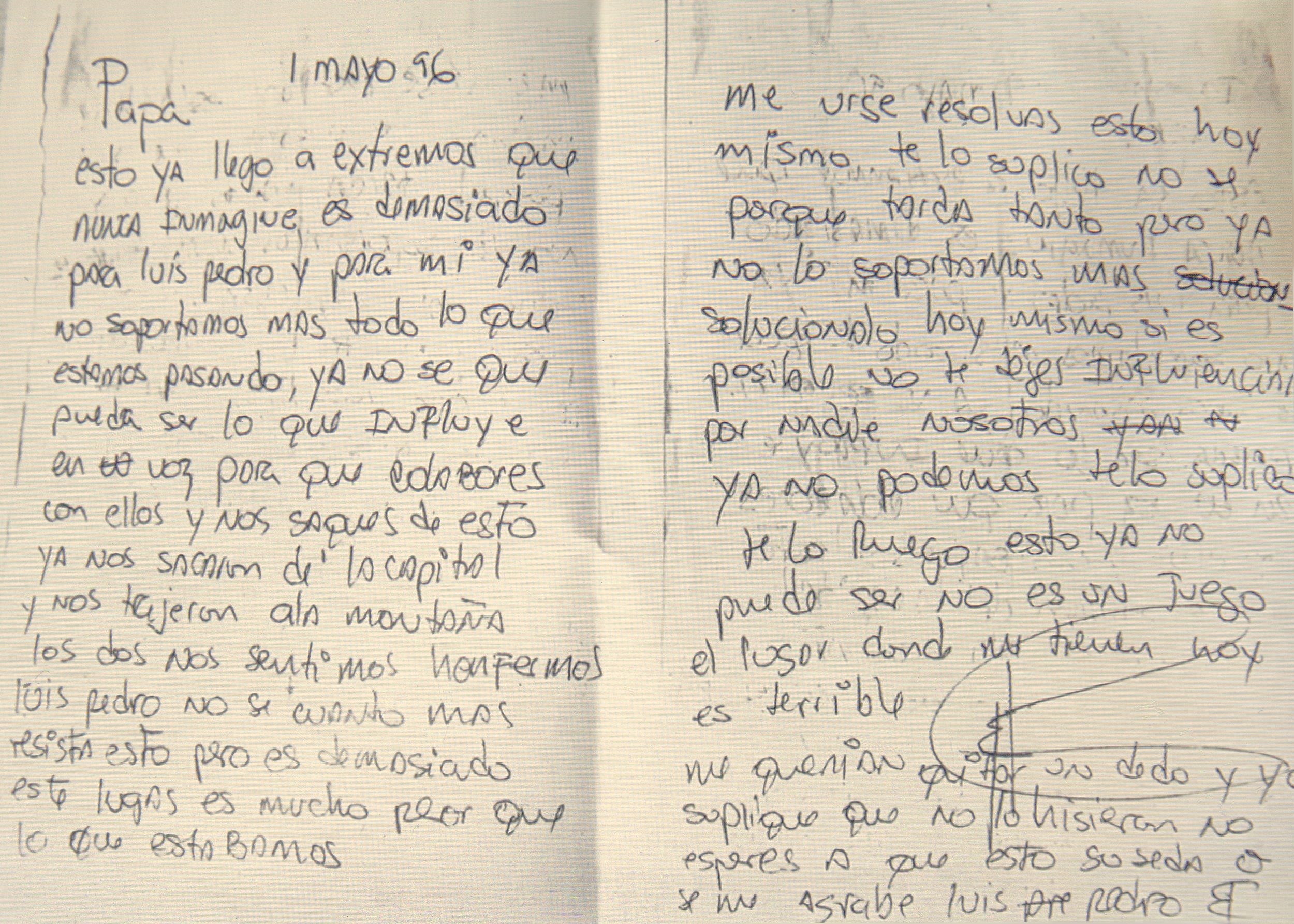

JTD: Tell me about Pasaco, 1996, which tells the story of how you and your father were abducted from your home in Guatemala and held captive for thirty-three days by an organized crime group known as Los Pasaco. How did this project come to be? What was your process for working on it?

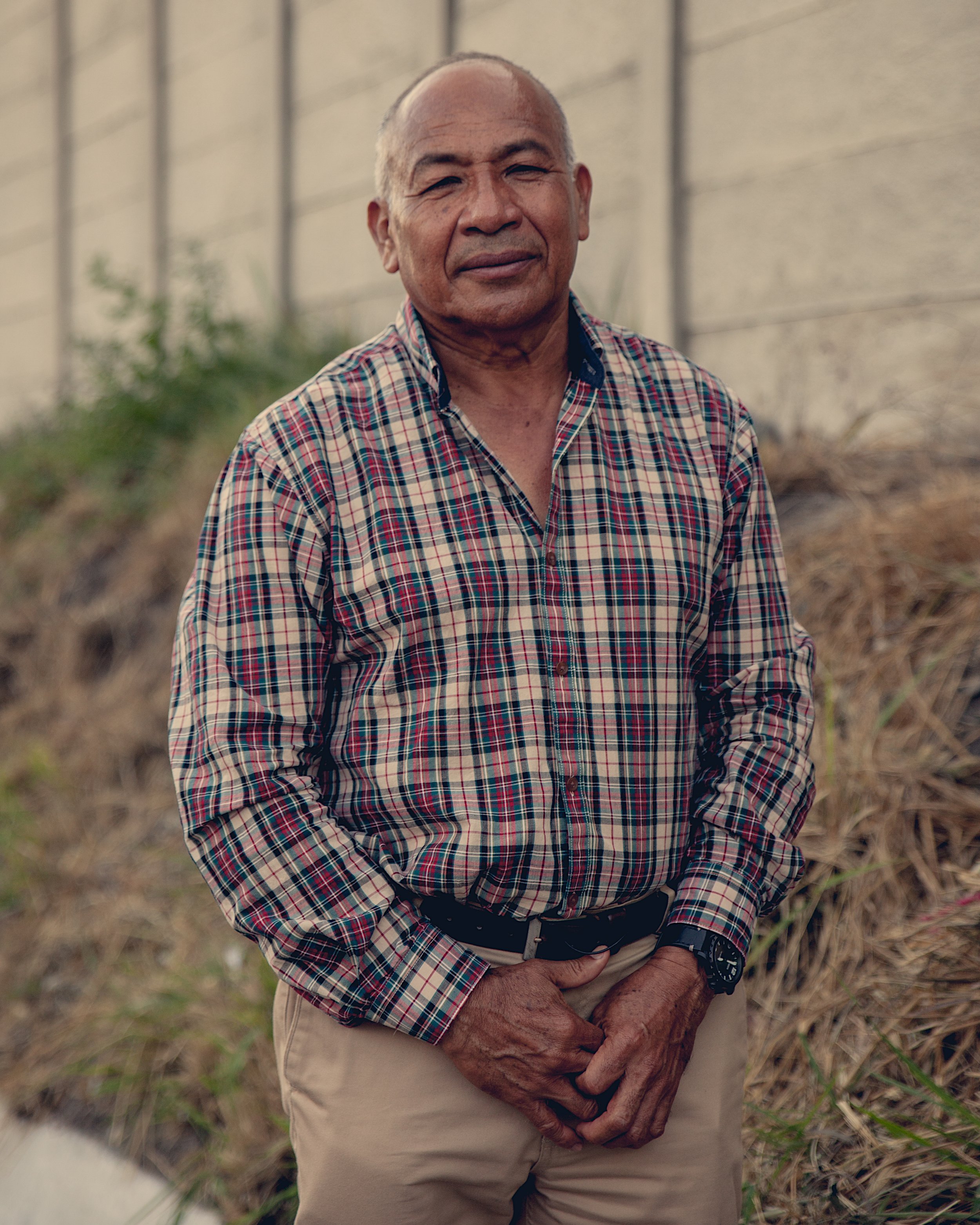

LC: During my studies in Barcelona, I began exploring the idea of working on a project about this story. At that time, I viewed it more as a personal and therapeutic project. It was mostly intended to finally give myself closure. As I started researching it and finding documents and audio files, etc., I was overwhelmed with emotion and fell into a slight depression. Many years later, around 2017, I began to develop interest in this story again. This time around, with a different purpose. I began doing research and coming up with a blueprint for the structure and concept of the project. In 2018, I launched a Kickstarter campaign in which I raised enough funds for me to travel to Guatemala and complete the project in five weeks. The first three weeks were mostly spent doing research and making all the final preparations. The final two weeks were nonstop. Going to locations, meeting and interviewing the individuals that were major parts of the story. Coincidentally, on the last day before I had to come back to New York, I bribed my way into the most notorious prison in Guatemala and met up and interviewed the leader of the group that kidnapped my father and I, Jose Luis Barahona Castillo.

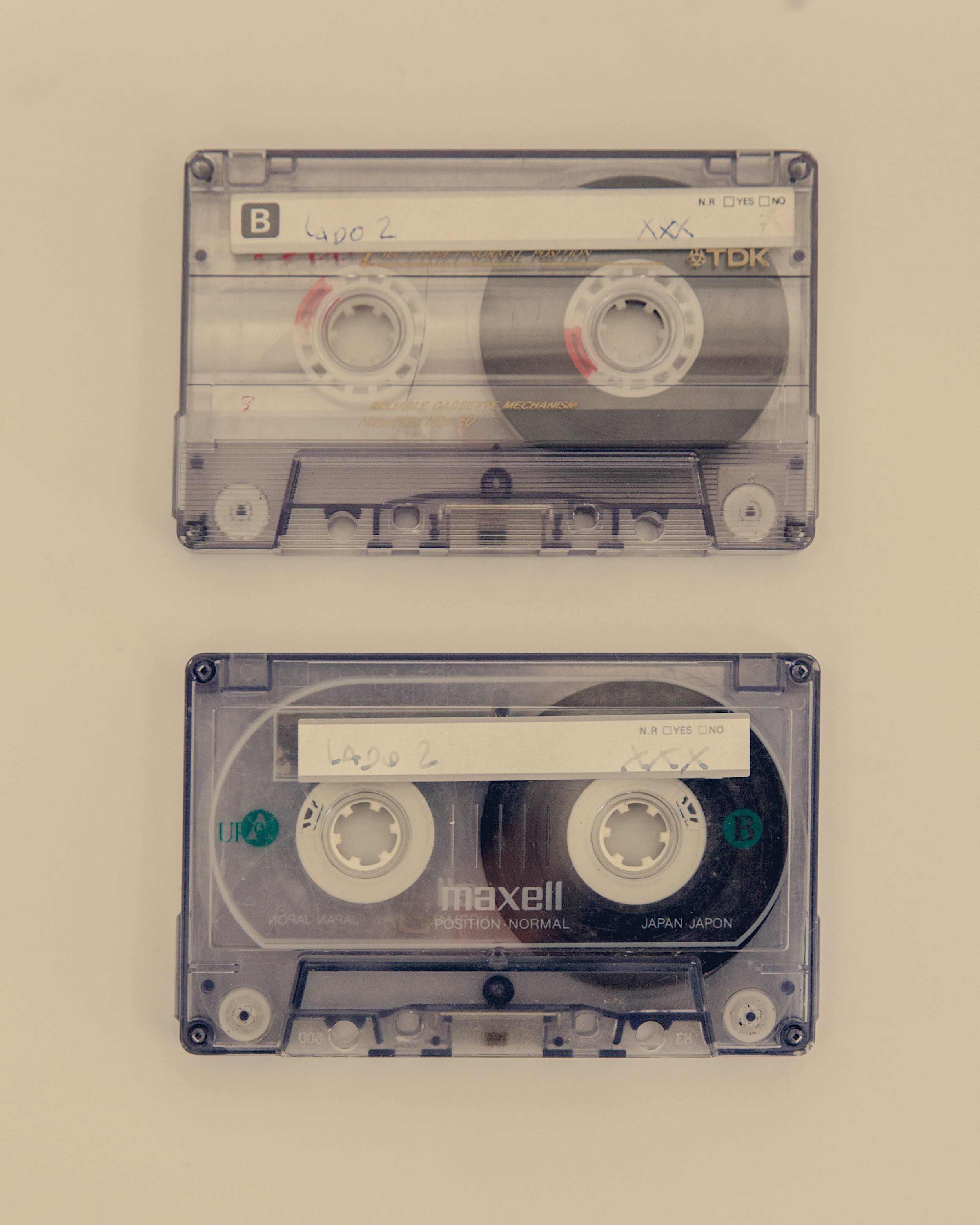

JTD: Wow, that’s amazing. One of the strengths of this project is your varied visual strategy. The series includes your own photographs of locations and people involved in the abduction, archival images of the original site of captivity, and images that function as documents, such as a photograph of your father’s missing finger, which was removed by the abductors and used as a tool to demand more ransom money, and another of cassette tapes containing recordings of conversations between the abductors and your family. Can you talk to me about this multifaceted visual strategy? What was your thinking behind combining different kinds of photographs?

LC: Since the beginning of my artistic career, I have been fascinated with the different disciplines within photography, such as: still life, portraiture, landscape and architectural photography. At different points of my career, this has been more of a problem because it was very difficult to find my style; but in this case, I think it was the best way to illustrate and communicate the many facets of this story. One of my main references for this project was Luis Molina-Pantin’s, “Testimonies of Corruption: A Visual Contribution to Venezuela's Fraudulent Banking History.” As a matter of fact, one of the images of “Pasaco, 1996” is a direct copy of the cover photo of that book. Other important references include Guadalupe Ruiz’s “Bogotá D.C.” book and the way she documents Colombia’s Estratos in such a clever manner. Rineke Dijkstra, Alec Soth and Wolfgang Tillmans’ work has also been of great inspiration and reference to me for many years.

JTD: This project is both a very specific story about you and your family and also one that engages with larger political and societal issues. What do you think about this duality?

LC: This duality has been very complex to understand and work with, but at the same time, very organic and familiar. Using past experiences and stories is the most efficient way to understand current conditions, in my opinion. Personally, this project has not had any element of closure for me, but I know it has for some family members, and I am glad to be a vessel for that.

JTD: Tell me more about that. How has your family responded to this work? Do you view them as collaborators?

LC: Initially, most of my family was a bit opposed to me doing this project and opening back up these old wounds. They believed that I would be putting most of my family and myself in danger. Although, with time, as they began seeing my progress, my determination, and my end goal, they all began collaborating and sharing all of their knowledge, memories, contacts, and ideas. In the end, I could not have done this without every single member of my family.

JTD: Do you view this project as having an educational or activist component?

LC: Yes, I have been very insistent on the fact that I view this project as having an educational and activist objective. There are a lot of elements in the project that I want to leave open-ended and allow the viewer to have their own conclusions, however, there are also strong personal opinions that I want to communicate, such as my firm opposition to capital punishment and the major part that governmental corruption has on civilian crime, such as theft, kidnapping, extortion, etc.

JTD: What do you imagine as the culmination of this project? Are you working towards a book or exhibition?

LC: From the first stages of this project, I have had a strong vision for both book and exhibition. As for exhibition, I had this firm idea that I wanted to exhibit the project in Guatemala first and then eventually show the project elsewhere. In March 2021, I had the wonderful opportunity of showing the entire project for the first time at La Erre (Espacio Cultural) in Guatemala City.

Since then, I have shown fragments of the project in CAV Gallery in New Mexico as well as in KappKapp Gallery in New York. My next major step is to convert the project into a book. At the moment, I am still looking for a publisher! Hopefully I can achieve this very soon.

JTD: In addition to this project, what are you currently working on, and what is on the horizon for you as an artist?

LC: One thing that I have been interested in exploring more is storytelling through short video documentaries, so hopefully I can immerse myself more into that. In addition, I am also interested in working more with magazines on photo stories, etc. As for my personal work, I have a few ideas in mind, but I do not want to focus on them as much until I have this work published in book form.

JTD: Wonderful, thanks so much Luis. I’m excited to follow along with your work and career and can’t wait to see this project as a book.

All images © Luis Corzo