Q&A: Lorenzo Triburgo and Sarah Van Dyck

By Hamidah Glasgow | February 3, 2022

Lorenzo Triburgo is a Brooklyn-based artist employing performance, photography, video, and audio to elevate transqueer subjectivity and cast a critical lens on notions of the “natural.” They often use a bright palette and a playful campiness to flip (or trans-) conventional power dynamics that exist between artist, subject, and outside viewer.

Their essay, co-authored with partner and collaborator Sarah Van Dyck, “Representational Refusal and the Embodiment of Gender Abolition,” will be published in the peer reviewed journal GLQ in spring 2022. They were a 2019 Workspace Resident at Baxter St/CCNY and an AIM Fellow at the Bronx Museum of the Arts in 2020. Permanent collections include the Museum of Contemporary Photography (Chicago, IL), Portland Art Museum (Portland, OR) and select exhibition venues include Bruce Silverstein, NYC; Photoforum Pasquart, Biel, Switzerland; Kunst und Kulturhaus, Berne, Switzerland; Dutch Trading Post, Nagasaki, Japan; Henry Art Gallery, Seattle, WA; Magazzini del Sale, Siena, Italy; and Oude Kerk, Amsterdam, the Netherlands as a winner of the international Pride Photo Award.

Triburgo is a full-time instructor at Oregon State University’s College of Liberal Arts online campus who teaches critical theory, photography, and gender studies with a focus on expanding liberatory learning practices in online environments.

Sarah Van Dyck is an Industrial-Organizational (I/O) psychologist who specializes in mixed methods research, blending and translating quantitative data with qualitative audio, visual, and narrative sources. Her professional interests include gender and identity at work, occupational health psychology and disparities in underrepresented populations, and LGBTQIA research in applied settings. She has conducted research with organizations such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Care System, National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Center on Work-Family Health and Stress, and Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research. Sarah was the recipient of a NIOSH Occupational Health Psychology Training Fellowship, and she has co-authored research articles in peer-reviewed publications and a variety of translational research outlets.

She holds a BA in Sociology/Anthropology from Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon, and an MA in I/O Psychology from Portland State University, where she earned a PhD in Applied Psychology in December 2021.

In past and current collaborations with her partner, Lorenzo Triburgo, she created For Love Understood In Desire, Monumental Resistance: Stonewall, and Shimmer Shimmer—video, performance, and photographic projects that represent a call to action to fight for the issues she addresses in her research and life’s work. Sarah and Lorenzo live and work in Brooklyn, New York.

HG: (Since the last time you talked with Strange Fire in 2017) There has been a shift to performative and collaborative work. I'd like to hear how those changes came about.

LT: There’s always been an element of performance in my photographs, whether in form or process. Painting all those Bob Ross landscapes for backgrounds in Transportraits felt performative. Even thinking back to my thesis work, I traveled to amusement parks and national monuments in order to put myself in spaces where I would be and feel marginalized as a genderqueer boi/babydyke, often mistaken as a teenage boy. In those two examples, it has to do with using my body to engage with artifice.

The shift to imaging performances of my body in projects since 2018 (Monumental Resistance: Stonewall, For Love Understood In Desire, and Shimmer Shimmer) is related to the political urgency both my partner Sarah Van Dyck and I felt around claiming trans and queer presence.

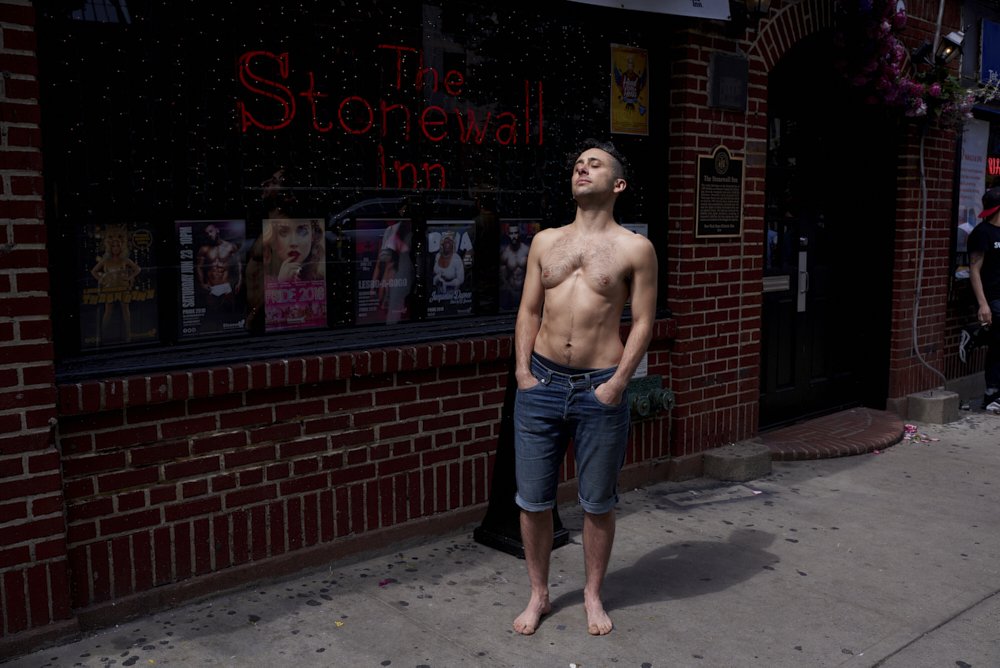

Monumental Resistance: Stonewall (MR:S) was the first of these pieces and also the first official collaboration with Sarah. MR:S is a performance, photography, and time-lapse video piece created during the 2018 NYC Pride Celebration. In 15-second increments, we created over 3,500 images as I stood in place before the Stonewall National Monument for 24 hours, often regarded as the birthplace of the LGBTQ civil rights movement. With my visibly genderqueer body exposed to the waist, I stood as a tribute to the transgender people of color who catalyzed the Stonewall Uprising of 1969, yet have largely been excluded from the ensuing civil rights advances.

I wanted to make a piece about resisting “resistance fatigue” (activist burnout from fighting the Trump administration’s ceaseless attacks on our rights). I wanted to stay standing for 24 hours and send a message of solidarity and hope that we can keep standing for the world we want to see.

SV: We always talk about how individuals can take action, but large-scale resistance can only be accomplished in community. My research with teams of direct-care providers working in 24-hour health care systems shows that no single individual can change the culture of a unit—a critical mass of people working in concert is required. So I said, “Let’s set up in front of Stonewall during Pride. I’ll be there with you, our friends will be there, and we can immerse ourselves within our community from midnight on Saturday to midnight on Sunday.”

LT: This is a perfect example of how our collaborations come about. The interesting turn of events was that as I was standing, shirtless and shoeless for 24 hours, feeling acutely vulnerable, occasionally having doubts about my ability to accomplish my 24-hour goal, our queer community gave me hope and solidarity. When someone saw that I was cold they gave me their jacket to wear, and later someone gave me their dog to hold! I was given encouragement in the form of kisses on the cheek, hugs, taking selfies with me, and inspirational cheers every step of the way.

SV: It was a beautiful experience.

LT: Sarah and I had just finished production of Monumental Resistance: Stonewall when the Trump administration attempted to implement a federally-mandated definition of gender as ascribed at birth according to genital attributes, and forever inalterable. When the administration also erased the word “transgender” from all federal websites, activists took to the streets and social media creating the campaign #WontBeErased.

In solidarity, I stopped taking testosterone after 10 years of transgender “hormone therapy” to create a durational performance and exploration of my body as a site of literal and metaphorical gender abolition. My body and its metamorphoses towards gender ambiguity became source material for Shimmer Shimmer, an ongoing series of figurative and still life photographs created in collaboration with Sarah.

HG: Can you tell me about gender abolition, and how the concept informed and led you to Shimmer Shimmer?

LT: Gender abolition means first recognizing gender as a social institution that is predicated on oppression, and not only functions as a hierarchy of identity markers but normalizes social structures as hierarchical, then being willing to imagine a world without it. We know so little about hormones and much of what we “know” is false (see Rebecca M. Jordan-Young and Katrina Karkazis’ 2019 examination of the dodgy origins underlying the cultural mythos of hormones in Testosterone: An Unauthorized Biography). Medical experimentation as an attempt to embody gender abolition felt like a fruitful direction.

SV: For three months or so we scouted different locations and ways of visually representing these ideas. We did test shots all over the city and upstate, but kept coming back to the idea of the historically gay section of the People’s Beach at Jacob Riis Park in Queens. This part of the beach is packed during the summer months, so we shot during the winter to be able to frame up the shots against structural elements without intruding on anyone. We kept our gear packed and ready, and checked the tides and windchill daily to be able to take advantage of days without precipitation.

LT: The first set of figurative images were created in the early months of 2020, and feature my glitter-adorned nude form in familiar, gendered, art historical poses, photographed by Sarah on location at Riis beach. The shimmer of glitter on my figure suggests a camp version of celestial presence and hints at a connection to astrology, an important mode of spiritual connection for our queer community. The accompanying still lifes of glitter as “constellations” are titled with astrological geometric configurations such as Sextile and Conjunction to reiterate this connection and signal to the viewer that titles of the figurative images such as Mars refer to the planet, not the (gendered) god. In this way, we trans the forms, figures, and gestures associated with painted and sculpted imagery of ancient Roman mythological figures.

Glitter here is also a representation of change itself—ever-elusive, perceived differently according to light and subject position. This is supported by the title Shimmer Shimmer, as it playfully alludes to Barthes’s notion of shimmer in the “Neutral,” in which they describe, “this integrally and almost exhaustively nuanced space is the shimmer... the Neutral is the shimmer that whose aspect, perhaps whose meaning, is subtly modified according to the angle of the subject’s gaze," and trans media scholar Eliza Steinbock’s use of this to describe visualizing transness in “Shimmering Images: Trans Cinema, Embodiment, and the Aesthetics of Change.”

The performative de-medicalization of my body, layered atop subtle gestural shifts of hip position or shoulder height, culminates in binaries coming undone, collapsing into one another or being non-existent where one might expect them to surface. My body's continued metamorphoses, and how my behaviors and gestures are perceived in relation to my visual presentation is an ongoing, durational performance taking place on and off camera that is rooted in a rejection of the pathologization of trans embodiment and a desire to occupy new subjective space.

Sarah and I discuss this in more detail in an essay we wrote for the peer-reviewed journal, GLQ entitled, "Representational Refusal and the Embodiment of Gender Abolition," which will be published in spring 2022.

SV: I am so excited for this issue of GLQ to come out. The special issue is Queer Fire: Liberation and Abolition and will be a superb reading list. In addition to the piece Lorenzo and I wrote about the political imperative to withhold figurative representations in their prison abolition work Policing Gender, the shifts that led to us using their figure in Shimmer Shimmer, and how prison abolition and gender abolition are integrally linked, the entire issue brings together activists, scholars, and artists discussing abolition as a queer politics. Until then, see the work of the other contributors as a place to start: Marquis Bey, Caia Maria Coelho, Stephen Dillon, Nadja Eisenberg-Guyot, Jesse A. Goldberg, Jaden Janak, Alexandre Martins, Alison Rose Reed, S. M. Rodriguez, and Kitty Rotolo.

LT: In Shimmer Shimmer, my physical transformations towards gender ambiguity, Sarah’s directorial gaze from behind the camera, as one that appreciates the transqueer form in the frame, and the associations created with our use of glitter—camp, queer astrology, a suggestion of transience based on light—work to support a framework of gender abolition in the context of (transqueer) embodiment and art history.

HG: It's great that you both have similar interests and that your research and creative work play well together. Tell us more about that dynamic.

SV: Working in the field of occupational health psychology, I focus on the intersectional social determinants of health. LT and I have overlapping research interests (the healthcare and prison systems for example) that are generative for both my independent research and the projects we create together. I primarily work with observational qualitative, audio, and video-based modes of collecting, analyzing, and translating research data, so LT and I have often used many of the same tools to address our separate areas of focus.

LT: A long time ago we agreed to approach our projects and way of life in a partnership (both coming from working-class backgrounds) with an attitude of “Where there’s a will there’s a way,” and “It’s not, ‘I can’t get this done,’ it’s, ‘how can I get this done.’” Our work feels like playing and we egg each other on to push further and have fun while doing it.

SV: Playing, yes, absolutely. We initially collaborated musically, and the components involved in putting live shows together–lights, staging, costumes, props all involve a theatricality that translates to our photography and video projects. The ouroboros that is NYC is another important aspect of our recent collaborations, Monumental Resistance: Stonewall and Shimmer Shimmer. The sense that the city is constantly devouring itself makes site-specific work feel urgent, especially for places that have significance for the queer community. Creating work tied to the queer section of Riis Beach for Shimmer Shimmer transmutes my anger over the destruction of historically queer NYC spaces into determination to fuel future resistance and hope.

LT: I knew that Sarah and I were on the right path when I found that more recent scholarship on Claude Cahun suggests that Cahun’s previously considered self-portraits are more likely a collaboration between Cahun and their partner Marcel Moore. Cahun was supremely influential on my art practice when I was coming of age, but also to my early sense of self. I loved talking with you about our shared admiration of Claude Cahun last summer.

HG: Ah, Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore, what I wouldn't give to be a fly on the wall of their house on the island while they walked their cats and leafleted the nazis!

LT: Indeed! I went to NYU when Cahun’s first show in the states was at the Grey Gallery, curated by Shelley Rice. As a teenager, the postmodern reading of Cahun’s work blew my mind.

HG: It's wonderful to be so open to all the ways that your creative instincts take you—the way you research and commit to a project, to know all about it before taking the project on. We talked about how problematic it is in the photo world that many people think that a camera gives them license to pursue an idea that they don't know anything about while unaware of the damage they are doing to people around them.

LT: Thank you for the comment on my process. I take the responsibility of image-making seriously and part of that is recognizing the horrific parts of photography’s history and the meanings embedded in its language that continue to be exploited. Photography has been and continues to be used in efforts to support racial hierarchies, as a tool to objectify and Other (see Louis Agassiz “scientific” photographs as “proof” of white supremacy, portraits of enslaved people to justify slavery, the origin of mug shots, advertising as a whole - which continues to draw upon these legacies, and disingenuous documentary/photojournalism, as a few examples). It is critical to me–at my core–that I employ visual methods that break from this history. And, the opportunity inherent in photography to critique these dominant modes of visualizing is why I am obsessed with it. That is why I chose not to photograph queer people behind bars in Policing Gender.

SV: The unintended impact of imagery is one area of crossover that LT and I continually discuss. As a research psychologist working in U.S. healthcare systems, I understand the concept of informed consent to participate in a research study to be a cornerstone of basic ethical principles for working with people in behavioral or biomedical research (see the Belmont Report, 1974). When LT was formulating the conceptual backgrounds for Transportraits and Policing Gender, we talked at length about how a similar ethical responsibility exists when making portraits.

HG: Lorenzo, one of your goals with the Policing Gender work is to show the work in every state. How many states do you have already? What does that mean to you to show it in all the states?

LT: I’ve brought Policing Gender and prison abolition workshops to 11 states thus far (some more than once): California, Missouri, Oregon, New York, Washington, Illinois, Colorado, Alaska, Tennessee (online), Rhode Island, and Pennsylvania. That’s five since my last interview with Strange Fire and I can feel the momentum around Policing Gender and prison abolition growing, which is exciting and necessary.

My goal is to sprinkle seeds of prison abolition across the country. We need to end the systems of incarceration in the United States, full stop.

HG: Prison Abolition is becoming more prevalent in dialogue that I read and hear. It's a complicated issue to unwind a system that is reinforced through so many avenues socially, financially, etc. What is your recommended reading list for people who want to learn more about the issue?

LT: Prison abolition is about de-normalizing prisons and redirecting resources from policing and prisons to social supports like healthcare, education, housing. This would mean that people with mental illness would get the care they need in order to be safe for themselves, and others, instead of cycling in and out of prisons. It means addressing the root issues of poverty (like racism) that lead to non-violent “crimes” as a form of survival.

LT: Reading list

• Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex, Eric A. Stanley and Nat Smith.

• Are Prisons Obsolete?, Angela Davis.

• The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, Michelle Alexander.

• “Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey, 2011.” Grant, Jaime M., Lisa A. Mottet, Justin Tanis, Jack Harrison, Jody L. Herman, and Mara Keisling. Washington: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.

• Queer (In) Justice: The Criminalization of LGBT People in the United States, Joey L. Mogul, Andrea J. Ritchie, and Kay Whitlock.

• Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison System, Michel Foucault

• Can’t Catch a Break: Gender, Jail, Drugs, and the Limits of Personal Responsibility, Susan Starr Sered and Maureen Norton-Hawk.

• Punishment and Social Structure, Georg Rusche and Otto Kirchheimer.

• Carceral Capitalism, Jackie Wang

• The Struggle Within: Prisons, Political Prisoners, and Mass Movements in the United States, Dan Berger

• Fugitive Life: The Queer Politics of the Prison State, Stephen Dillon

• Queer Fire: Liberation and Abolition, a special issue of GLQ, published by Duke University Press, edited by Jesse A. Goldberg and Marquis Bey (forthcoming spring 2022)

HG: Thank you both for taking the time to chat.

LT and SV: Thank you!

All images © Lorenzo Triburgo and Sarah Van Dyck