Q&A: krista wortendyke

By Jess T. Dugan | Published November 12th, 2015

Krista Wortendyke (b. 1979, Nyack, New York) is a Chicago-based conceptual artist. She received her MFA in Photography from Columbia College in 2007. Her ongoing work examines violence through the lens of photography. Her images are a result of a constant grappling with the mediation of war and brutality both locally and globally. Her work has been exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in the exhibition Crime Unseen, at the Packer Schopf Gallery and David Weinberg Gallery in Chicago, SOHO20 Gallery in New York, and many other venues across the United States. Additionally, Krista’s work is part of the permanent collection at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston and the Museum of Contemporary Photography. Krista is currently an adjunct professor of photography at Columbia College Chicago and Northeastern Illinois University.

Jess T. Dugan: Tell me about Killing Season. How did it begin, and what was the impetus for making the work?

Krista Wortendyke: My wife and I often take walks when we get home from work. On May 5th of 2010, a man killed himself and his two sons in his yard just a few blocks from my house in Chicago. I became obsessed with walking on that block to see if I could figure out where the murders took place. I thought that when I walked by, there would be an aura of sorts that would let me know that this was the spot, but that never happened. A few days after this murder/suicide, the CEO of Metra threw himself in front of a train, there was a shoot out on the Dan Ryan Expressway that left one dead and several people injured, and a man walked into the Old Navy in the Loop and killed his girlfriend and himself all before noon. When I talked to people about what happened, the common response was, “It’s not even summer yet.” That statement simultaneously disturbed and intrigued me. What did that mean? Things would get worse? This was just the beginning? These questions, coupled with my interest in the lack of being able to identify where my neighbors were killed, inspired me to want to visit and photograph every site of a homicide in Chicago that summer.

JTD: What is the process for making Killing Season? What were the logistics of photographing the sites?

KW: When I had the idea for the work, I had absolutely no idea how I was going to make it happen. There were so many obstacles that I had to figure my way through. First, none of the actual addresses for the homicides are published. Second, I was not about to go waltzing into unfamiliar areas of Chicago where people are getting killed by myself with all my camera equipment. Third, I didn’t even have a car.

I knew that I wouldn’t be able to accomplish any of this without the help of a police officer. My cousin had a good friend that was CPD and offered to introduce me. A week or so later, I found myself shooting guns at a range in the suburbs trying to convince a police officer to help me out. He happily agreed. I am pretty sure he thought he was going to help me for a day or two, but in reality, it was roughly 6 months of 6 am pickups 3-4 times a week to go out and photograph together. The project turned into a collaborative effort even though the police officer I worked with would never claim any ownership over the work.

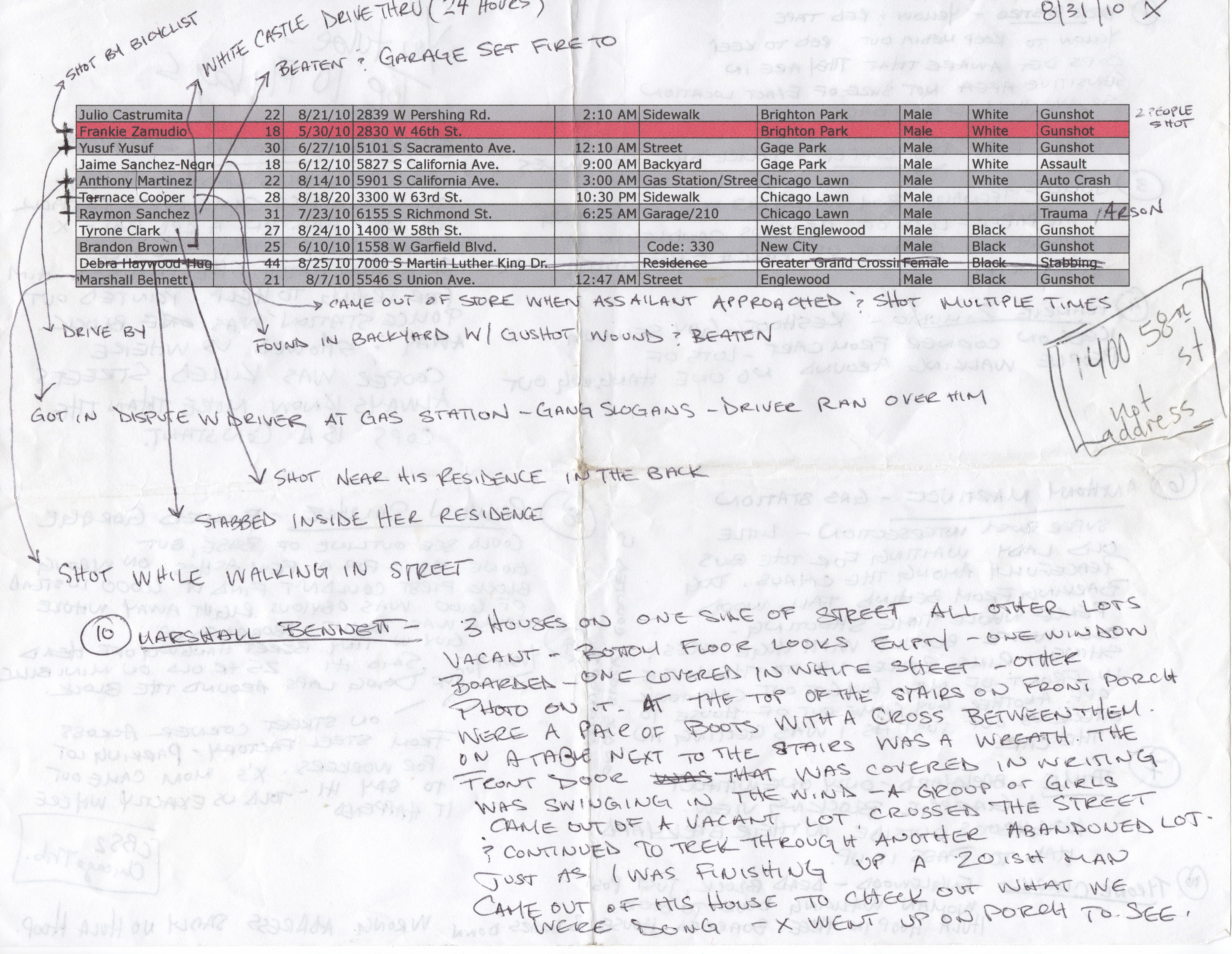

A spreadsheet from a day of photographing for Killing Season

Beginning on Memorial Day and ending on Labor Day, I tracked homicides within the city limits. Once the crime scenes were processed and the red tape was taken down, I visited and photographed the site of each murder. There were 172 homicides within that time period of roughly 3 months. As I documented the sites, I recorded my experiences on a blog (killingseasonchicago2010.blogspot.com), listing the names of the deceased with information about the incident that led to their death and a map of the location. As I processed the images, the maps were replaced with those photographs.

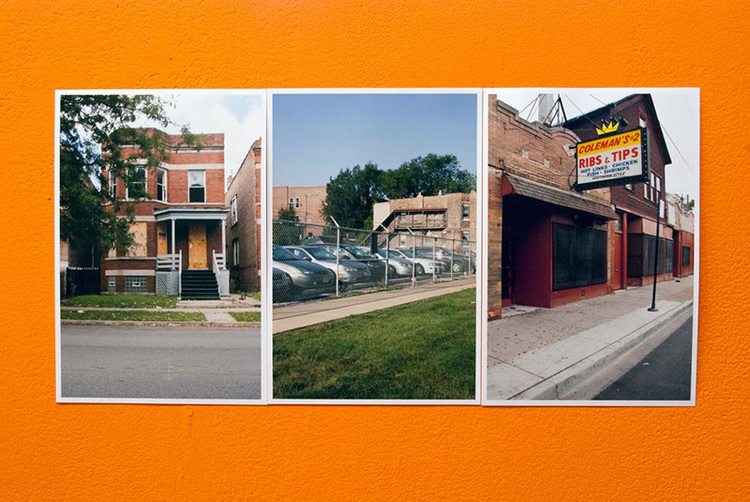

I chose to photograph early in the morning before people were out on the streets in order to create the people-less images I was looking for. We headed out, info in hand, at around 6 am to photograph roughly 7-8 sites. We were usually only able to photograph 4-5 sites before the locations got too busy. We drove past one site 26 separate times before we found it quiet enough to photograph. At the site of a well-known drug corner, we eventually called in an on-duty cop whose presence sent everyone into hiding. While we talked to people at a number of the sites and heard stories about the murders and the neighborhoods, often there was not a person in sight.

Images from Killing Season

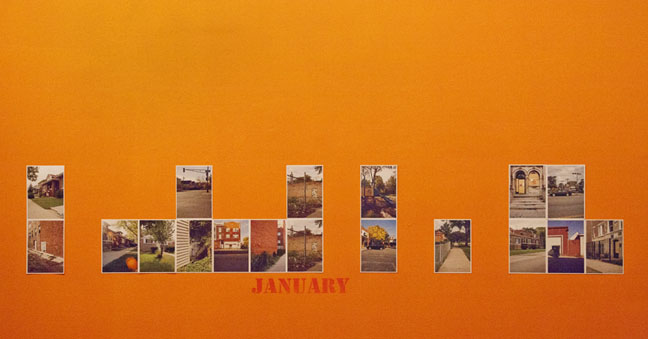

JTD: One thing I have always found so moving about Killing Season is the way you install it, as a graph organized by the number of killings that happened each day, ultimately resembling a city skyline. This is a very powerful visual representation of something we are used to hearing about simply as a statistic, if we hear about it at all. How did you decide on this kind of presentation, and how do you hope viewers engage with it?

KW: One of the main goals of the project from the beginning was to find an impactful way of demonstrating the reality of the overwhelming number of people killed in Chicago in a summer. I knew that I wanted to create a physical manifestation to represent those homicides rather than an easily ignored statistic represented as a number on a page. Initially, I wanted to make a book of the photographs, thinking that the sheer thickness of the book would speak volumes about the problem. Ultimately, in manipulating the photographs in Photoshop and arranging them as a visual bar graph, I discovered that it mimicked a city skyline. As I continued to play with the form, I found that I could organize it so that it also communicated specifics about the dates of the represented homicides. As soon as I was able to work all of this info into the skyline imagery, I knew that was the form I needed to adopt to display the piece.

Killing Season being installed outside of the Violet Hour in Chicago, IL

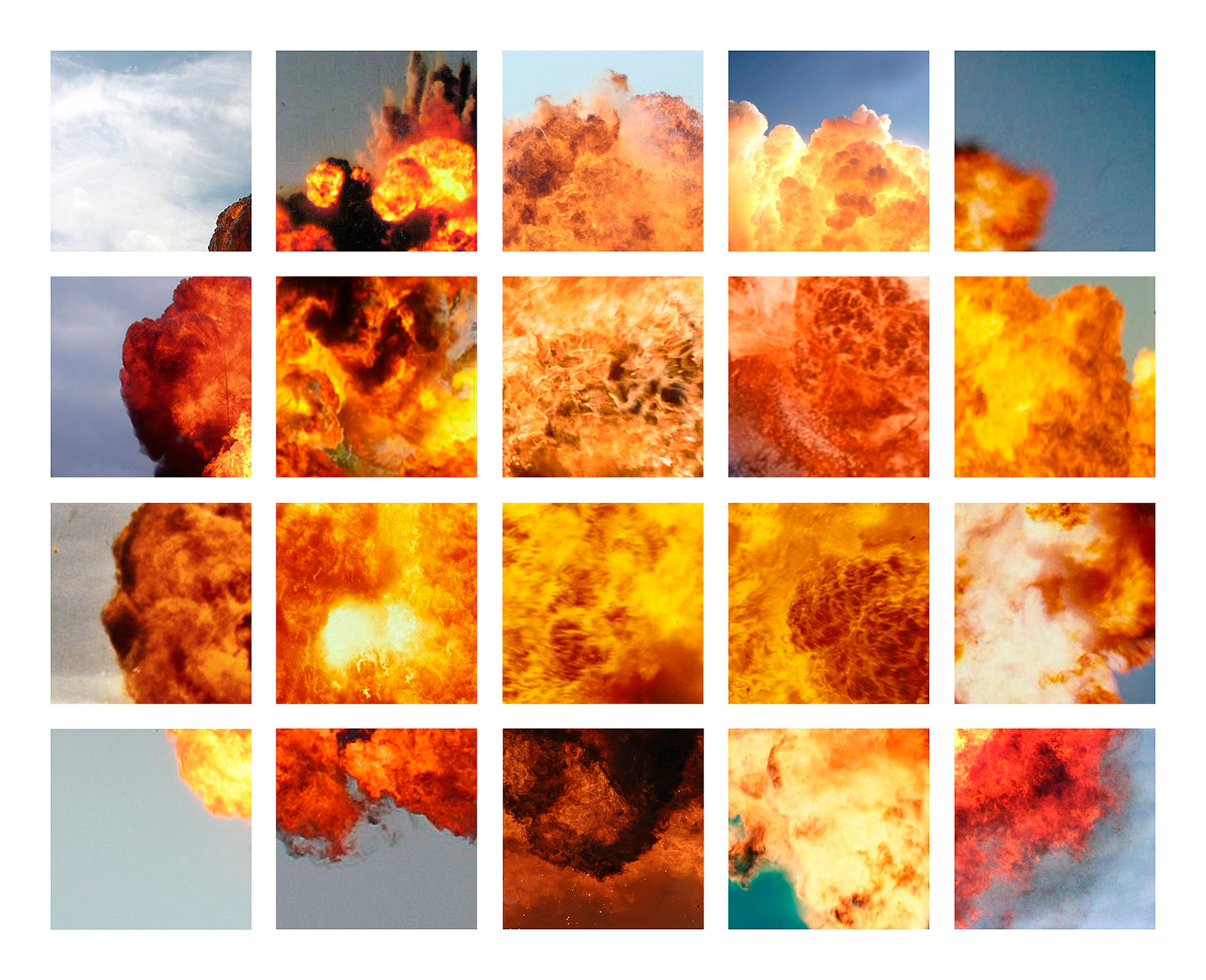

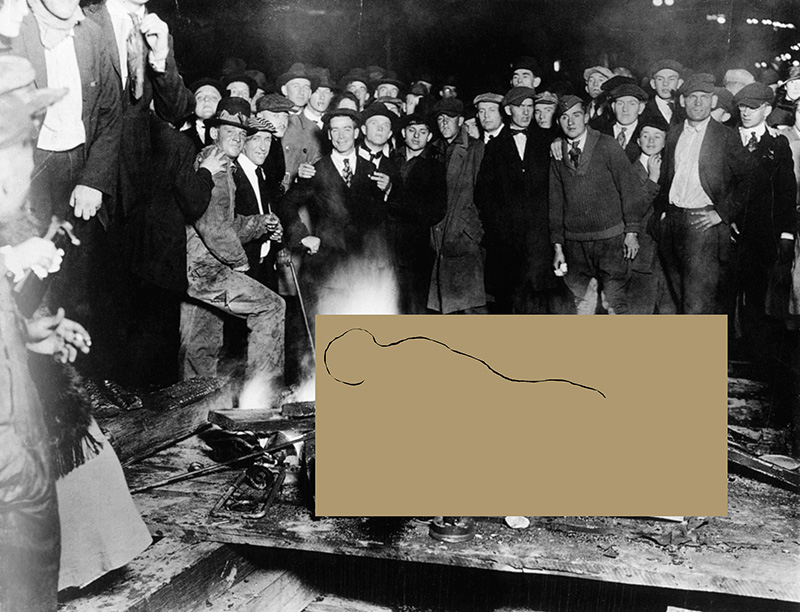

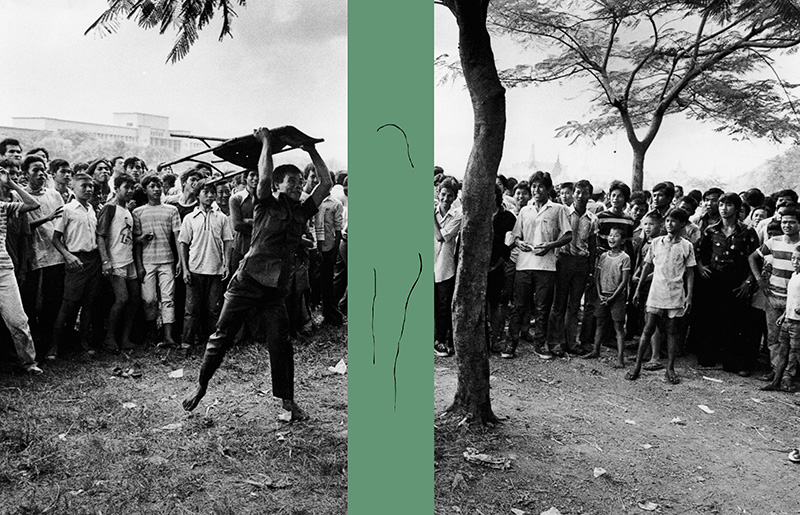

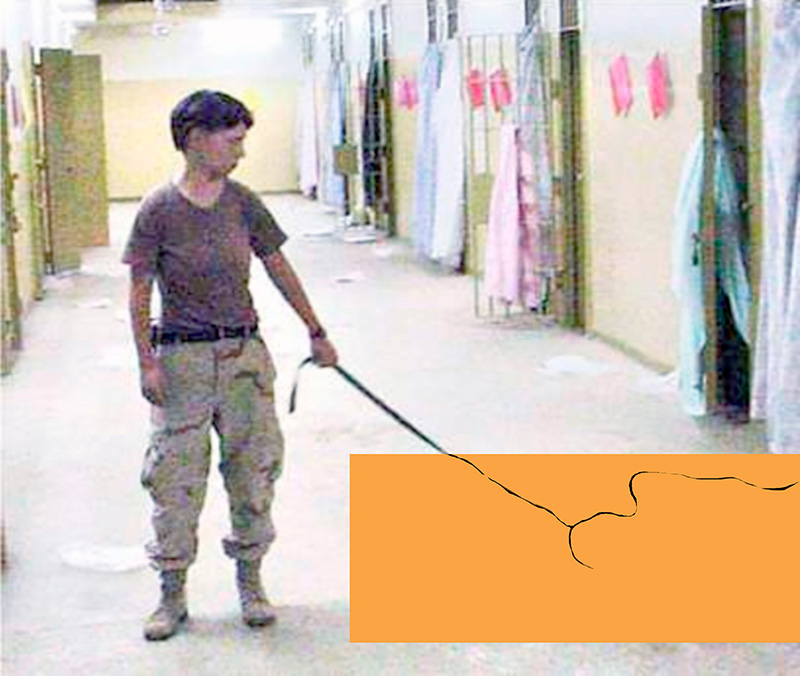

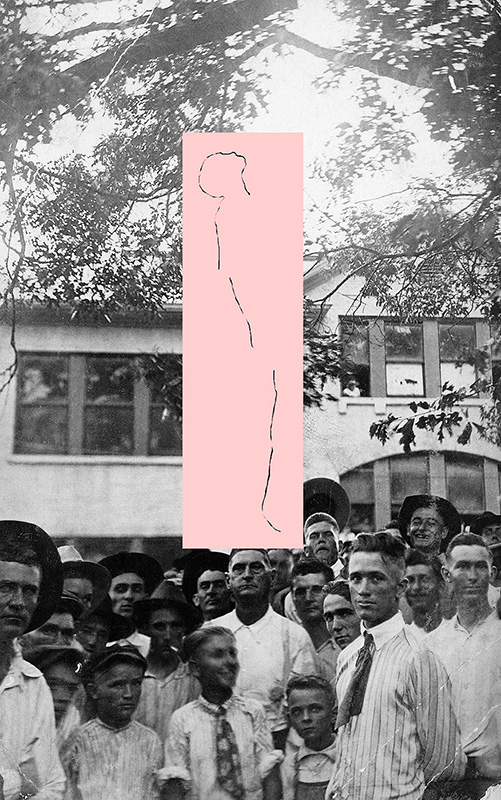

JTD: In Killing Season, you are showing us the sites where murders occurred, but are not showing us the murders themselves. In Interventions, you take a similar tactic, showing us images of horrific acts- lynchings, beheadings, beatings- but obscuring the portion of the photograph that shows the actual victim. Why do you use this strategy? Do you think that we, as a culture, have become insensitive to violence when it is depicted directly?

KW: Our environment is saturated with violent imagery. We witness imagery of disaster, devastation, brutality, and death every day whether it be through the news, in movies, or in video games. Our easy access to information has made us into perpetual witnesses of tragedy. We steadily consume this imagery without taking the time to process it. For me the question becomes, how can I, or we, avoid being passive when violence and devastation become common sights?

In my work, I seek to present or re-present this imagery in a way that disrupts the relationship we have to violence in visual media.

By blocking the spectacle of the dead bodies in my images of murder, whether by covering it or omitting it entirely, I am slowing down our habits of consumption and making the viewer think about the image in a new way. If part of an image is blocked out, the viewer is forced to imagine what might be there. Because it breaks from the ordinary structure of things, they cannot consume it without processing it first. They are forced to imagine the atrocity behind the block or the body that may have been lying in the street. Most of the time, what we imagine is worse than what was there in the first place. By not giving the viewer what they expect, they are forced into a position where they have to think about what they can see and by extension, what they can’t see. This challenges what the viewer thinks they see and what they think they know. By slowing them down, I am able to start a dialogue about both the new interpretation of the image or scene and the old, which in turn helps to save it from the habits of ordinary consumption.

JTD: For Interventions, how do you find your source imagery? What kind of ethical concerns have you faced while making the work?

KW: I take some of my images from books, but I spend a lot of time Google image searching and collecting those images in a massive database on my computer. It’s interesting because my ethical concerns have very little to do with the appropriation of imagery, but instead are much more focused on issues of representation. I struggle with presenting images of people that have been cruelly murdered in a way that devalues them as individuals for the sake of the larger ideology I am investigating. I also grapple with the idea that each of these images of somewhat sanctioned murders are considered outside of their relationship to the larger nuanced cultural narratives that they originated in. What I have accepted is that expression always comes at a cost to truth.

JTD: Your work is obviously politically motivated and socially relevant, especially now, with the massive struggles we are facing in the United States in regards to racism, gun violence, women’s health, LGBTQ equality, etc. What do you view as the role of art and the artist in this conversation? Do you feel a responsibility to make socially-engaged work?

KW: I’ve struggled with this question a lot in the recent past.

In his essay “A World Like Santa Barbara,” David Hickey asserts that art has the ability to civilize. He doesn’t attribute this to the subject matter of the art, but instead says that “art is a safe place where we may non-violently come to terms with disorienting situations and adjudicate their public and private relevance in a public discourse.” There is an assumption that since I make art about social issues that it is my responsibility to take that art and use it to make change. I am not a social activist though. I see my role as someone who asks questions and presents issues for viewers to look harder, longer, and more thoughtfully at so as to ignite conversations about questions that I am not hearing people asking in the common discourse.

I make art to ask questions and to subvert the common public discourse to give people a safe space to approach uncomfortable topics and ask them to consider them anew. I do not see my role as a social activist but I am aware that art does not exist in a vacuum and has an impact on culture and change.

JTD: What’s next for you? What are you working on now, and what are you most excited about?

I have been working on an interactive website for Killing Season that is due to launch in the next month or so. I’ve also returned to the Intervention project and have begun looking at contemporary photographs I have found that are not entirely dissimilar to the historical images in the series.

All images © Krista Wortendyke