Q&A: Kelsey Sucena

By Keavy Handley-Byrne | June 30, 2022

Kelsey Sucena (they/them) is a trans*/nonbinary photographer, writer, and park ranger currently residing on Long Island. Their work rests at the intersection of photography and text, often within the bodies of performative slideshows and photo-text-books. It is centered broadly upon the United States as a site for anti-capitalist, queer, and critical reflection. Kelsey is a recent MFA graduate from Image Text Ithaca (2020), Managing Editor of The Photocaptionist, and a freelance writer with contributions to Float Photo Magazine, Rocket Science, and 10x10 Photobooks.

Keavy Handley-Byrne: Let’s begin at the beginning. How did photography become such a large part of your life? What about it continues to keep you engaged?

Kelsey Sucena: I’ve been making pictures since I was a kid. I was in middle school when I inherited my first camera. It was a silver Motorola Razr flip phone with a two-megapixel camera. A hand-me-down from my sister.

At the time I had just begun volunteering on Fire Island, at the park where I still work. The natural landscape, the architecture, and the history were all so inspiring to me. Passing through Cherry Grove on my way to work at the Sunken Forest was probably the first time I saw pride flags flying high. It was the first time I encountered queer folk, out and proud and living their lives openly. I photographed it all enthusiastically, though for many years I failed to interrogate the source of that enthusiasm.

At the same time, I think I was growing increasingly alienated from the world around me. That puberty was a confusing time. It was the first time I began to really wrestle with gender as I found myself sequestered into teenage masculinity. Into roles and expectations I wasn’t always comfortable with. I was confused and frustrated, and I ended up repressing those feelings for a long time. I didn’t have the words to describe it, let alone any framework for understanding the source of that discomfort. It was (and honestly still is) difficult to feel grounded.

Photography was the most effective tool I found for keeping me rooted. When I felt myself drifting off from the world, that Razr was a novel way of re-engaging with it. To be honest, I think this is still the role photography plays in my life. When I dissociate or sink into a depressive episode, the camera is always there to bring me back. At least when I have the energy to pick it up.

From “Coming Out Stories,” New-Bodies.net

The Rose Trimmer, from Before I Go

KHB: It’s so refreshing to hear that your first camera was a cellphone! My first was a one-megapixel Kodak point-and-shoot, similarly lo-fi. Do you feel that the limited nature of the cell phone impacted your current practice? Do you still take cell-phone pictures?

KS: You know, I’m not really sure. The phone was a bit of a gateway drug in the best possible way. It’s been said before, but part of the appeal of photography is its democratizing effect. Photography is a relatively accessible medium in that, as long as you’ve got a camera (or cellphone) you can, at least in-theory, make images you like to look at. Other mediums tend to take more time, though I do think of writing as being similarly democratic.

I didn’t come from an artistic background (I was the first person in my family to graduate from college, let alone art-school), so most artistic mediums were alien to my family culture. Photography made sense to us though, as its commercial and interpersonal applications are self-evident, at least in the illusory quality of a market set on making itself seem bigger than it is. For as long as I can remember I’ve struggled to make my work “work” despite financial instability, and despite feeling adrift in a world that was so foreign to my upbringing. Art, including photography, demands the kind of discipline that stability can afford, but with photography that discipline can also emerge from enthusiasm, excitement, and a willingness to be attentive to what’s around you.

That’s all to say that, no, I’m not really making phone pictures much these days (except that I’ve been trying to figure out selfies since I began to transition). But I also know for a fact that without my sister's hand-me-down razr, I wouldn’t be talking to you today.

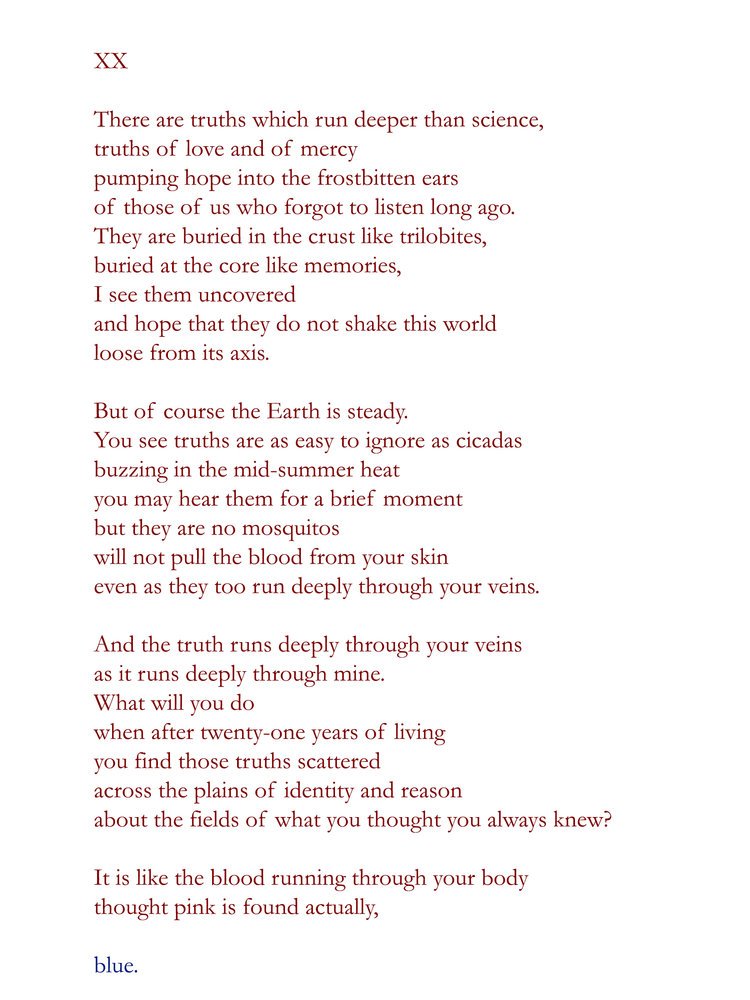

XX Truth, from Before I Go

Rosehips, from Before I Go

KHB: You are a prolific writer as well as a photographer, and lately have focused on the art world itself as a subject, especially as it relates to progress and community. In the course of the global COVID-19 pandemic, how do you maintain and grow your artistic community? What does that community look like outside of the confines of Institutions? (I feel like that word should be followed with a trademark symbol.)

KS: Haha. Yeah. You can definitely use a ™ there.

If I’m honest I’d say that, regarding my own “artistic community”, the trend for me since the start of the pandemic has generally been recession. I have far fewer art friends now. Closer friends and more meaningful relationships, maybe, but fewer.

Part of that is related to the pandemic. Part of that is just geography, living out here in the hinterlands of New York and away from the geographical center of that world. A big part of it is my day job, being too busy to keep up with folks the way I’d like, and some of it may just be because I’m getting older.

Without a doubt though, the thing that has most precipitated my feeling of disconnection has to be the growing sense of disillusionment I have about the “art” market broadly speaking. It's all so unstable, competitive, inhumane, and unsustainable. It’s hard to participate in the “art world” (big scare quotes there) without running the risk of crushing yourself in the process or at least going into it with external resources (money and/or familial support) to begin with.

On top of this, institutional resources are shrinking as a result of decades worth of austerity, and the once expansive space of the internet and social media seems to have been thoroughly closed off. I’ve been slowly retreating from Instagram and Facebook since I started to transition. The harassment I’ve received on those platforms has left me a bit anxiety-ridden. As I retreat from those platforms I’m starting to realize the role they used to play in fostering a sense of community, while not necessarily fostering that community in any tangible ways. It's sad to let that illusion go but I think it's healthy too.

That’s all to say that I still believe in community, but I’m less sure these days about how to grow it. I have this vision of a unified coalition of artists, organizing our labor to secure a better, more stable world for ourselves, but that may be a long way away, and there are probably more important things to tackle right now. In the meantime, I’ll let my core relationships deepen. If I can’t expand my artistic community, the least I think I can do is water the one I have.

From Art Can’t Save Us (and that’s ok), New-Bodies.net

From The End Of Days, New-Bodies.net

KHB: I definitely understand the desire to retreat from those platforms. As my “professional” life (more big scare quotes) has moved more and more online, become more intertwined with the ‘identity’ I’ve created on Instagram, I find myself with a greatly lessened desire to spend time on social media. It feels like a chore now.

KS: I wonder how much of that is related to changes in your life, and how much of that feels like it could be because of structural changes to the platforms (Instagrams emphasis on video content for example)? Do you think there’s something different about the platforms, or do you think there’s something different about you? (asking for a friend)

KHB: Interesting question! I hadn’t thought of it that way, but it’s probably both – I’ve never been much of a video maker, and always liked seeing my friends and peers’ content more than random, algorithm-driven content. Not to mention the Pandemic burnout we’ve all been experiencing. Even more, it might be the relentless tide of bad news for trans people like ourselves. But perhaps it’s partly that, as you mentioned, I’m more disillusioned with the art world as well – less focused on sharing my work to get eyes on it, and more invested in the making practice instead.

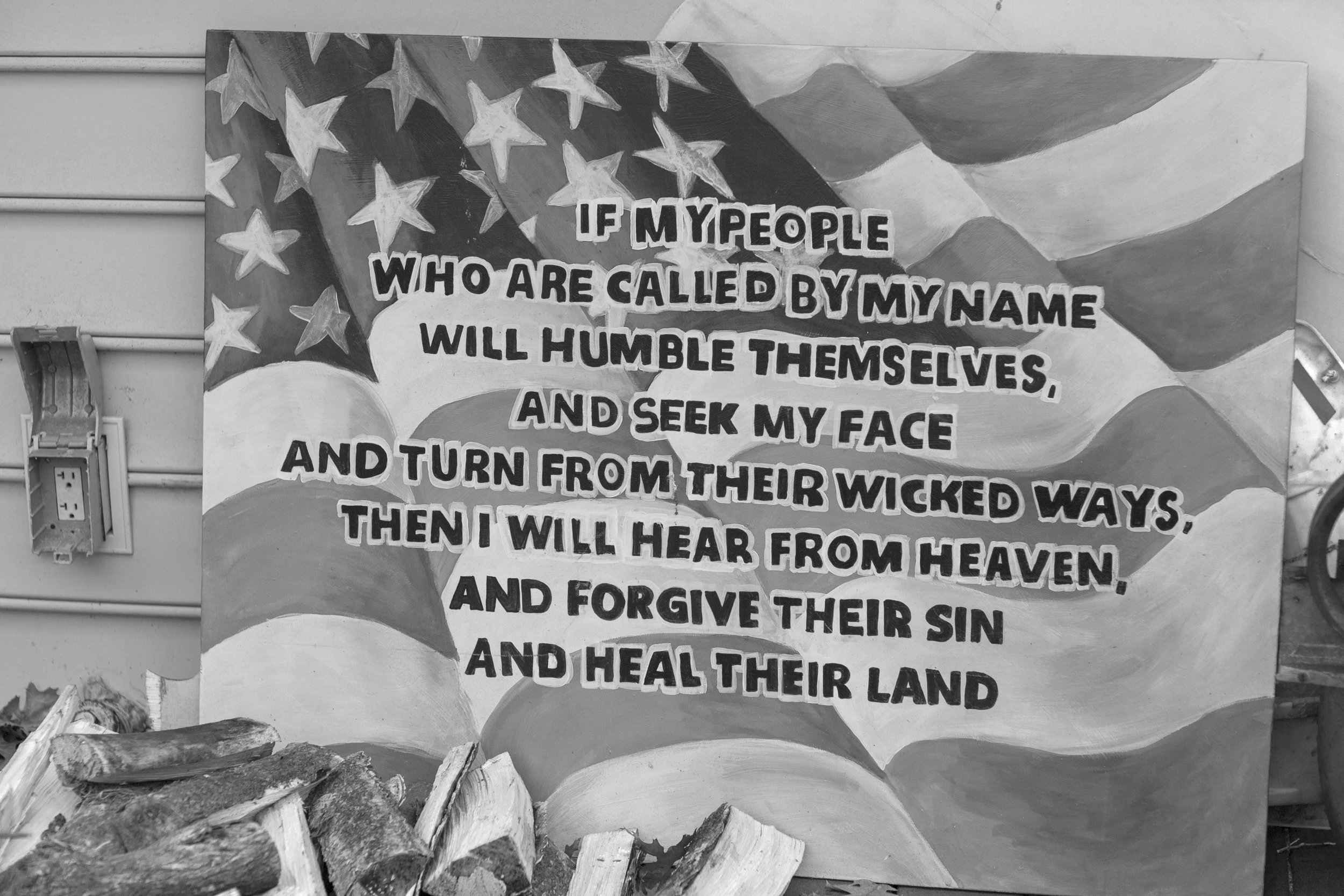

Over the course of your project, Paralytic States, you used the camera to investigate a shift in the political climate that came to a head with the 2016 election of former President Donald Trump. I’m interested, since the election of Joe Biden to the same post, how this project continues to develop, especially in relation to the current anti-LGBTQ legislation that seems to be spreading across the nation. How do you contend with these issues through photography, if, as you so eloquently write, art can’t save us?

KS: It’s been immensely challenging to work on this project over the course of the pandemic. Between quarantine, and being generally broke, I haven’t been able to travel the way I’d like in order to continue making this work. And yet, with the recent wave of anti-trans and anti-LGBTQ rhetoric currently sweeping the consciousness of the American right, PS feels more urgent than ever. I’m currently trying (and mostly failing) to secure grants or some other form of institutional support so that I can embark on another phase of the project. I need help to make it happen, but it’s also a tough sell. We’ll see how it goes.

But yeah, for decades now the United States has been locked within a state of paralysis around pretty much everything. Trump's election seems to have both broken that paralysis and underlined its real danger. The election of Joe Biden has done little to untangle the very toxic fascisms emerging as a result of that paralysis. To me, his election underlines a profound failure of imagination, the squandering of what could have been a break from our fascistic slide.

In some ways that means we may be in a more dangerous place now than we were even a few years ago. It’s hard to say. I think the scapegoating of trans people is a bad sign. The right (Republican and Democrat alike) is preparing to ride that wave into the midterms, and it seems like it'll be a strategy that pays off for them. Whatever is on the other side of that is a little scary, though certainly not written in stone.

As to the role that photography may play in light of all of this, I’m not certain. I believe that it’s important to stare unflinchingly at the thing that shakes you. This country feels so dangerous, so intimidating, so ravaged, so traumatized. I feel it necessary to attend to that trauma through photography, if only because photography is a good way to study the thing.

I’m no longer convinced that photography (or art more broadly) can fix these problems, or that it can even begin to counter the collective sense of alienation that is present at the core of these issues, but I do believe that photography remains a useful tool for myself. With photographs, I can study the United States. I can make friends and feel less disconnected. I can begin to understand why people are so terrified of the future, so hysterical about trans people, and so ready for a break, any break, from the neoliberal paralysis of the last few decades. I don’t know if that’ll help the world, but it does help me.

Chevy Lace, Bushwick, 2019, from Paralytic States

Dad, Long Island, 2018, from Paralytic States

View of Golden Gate, San Francisco, 2019 from Paralytic States

Election Day, Seattle, 2016, from Paralytic States

KHB: I think that’s a great way of looking at it: not a universal fix, but certainly a personal balm. I know you’re also an educator – I wonder if this is an idea you bring into your teaching as well?

KS: You know, I think for the most part my students are light years ahead of me in that regard. That’s one of the pleasures of teaching, right? I leave class every week feeling inspired by photography in ways that I hadn’t considered. I’m lucky to have some truly brilliant students where I teach.

Quite a few of my students are working on projects that I might describe as being “culturally therapeutic”, in that they engage with tough questions relating to everything from mental illness to social justice (intertwined as those examples are). I can see them using photography as a space to better understand themselves and the world. That balm, as you coined it, seems to work wonders for them and frankly, it works wonders for me.

I actually just caught a performance by the comedian Mae Martin that feels relevant here: Toward the end of their set they tell this story about a Buddhist proverb. In it, a man is pursued by a beast of some kind before falling into a well. He manages to grasp onto a branch, but knows the solution is temporary. He can't climb up or the beast will get him, and he knows he can't survive the fall. On the cusp of death he notices some sap on the tip of the branch, and tastes it, and that’s it. Maybe that’s where we’re at? Artist’s on the cusp of any number of bad things, just tasting the sap before we fall? Maybe that’s ok.

I wonder if you see the same in your students? This engagement with photography as a kind of therapeutic form or balm? I suspect that this is where students are at right now given the pandemic, the climate crisis, and everything else they’ve grown up and into, but my sample size is limited.

KHB: I certainly have found something similar among my students. Teaching non-majors this year, I noticed a tendency to use my assignments as a reason to, put simply, have fun. Many of them were feeling the pressure in their own media, and used photography as an excuse to just go on a walk and notice things. Personally, I’ve found that’s a balm for me as well; taking the time to really see things that are around me for their beauty, or their tragedy, even. It surely is the joy of teaching, I think, to be inspired by those who are so new to the medium of photography, to return to those simple pleasures that it has to offer, those early moments of visual excitement that so inspired me as a young photographer. In that vein, I want to go back to some older work. Following Seas explores the cadets in your high school ROTC program, and revisits these same subjects six years later. What motivated you to make the earlier images when you were in high school? How did your perspective shift as you revisited these photographs as an adult? Does your perspective continue to shift, or does this project feel firmly in the past?

KS: Oooph! Following Seas! Now there’s a deep cut. I guess it's up on my website so I shouldn’t be surprised that you’ve seen it, but it’s not a project folks ask about very often.

What motivated me to make those pictures in high school? You know, at the time I thought I was gonna join the Navy. I was super insecure in my gender and thought that doing what my Dad did (he was a Petty Officer in the Navy back in the day) would help me to secure the “discipline” I thought I lacked. I joined that ROTC program to give myself a taste of that future and, gratefully, realized it wasn’t for me. Photography ended up being the thing that saved me from that future, as I managed to swindle my way into SUNY Purchase to study it.

Those kids, the other cadets of the program, were all just as stuck as me. Few people leave my hometown outside of going to college or joining the military. I photographed them because that's what you do. You take pictures of the people around you and those were the people around me.

When I rediscovered those negatives in an old class binder, I was thrilled. Six years had gone by and so much had changed. The pictures spoke to the amateur thrill of photography. I was delighted by how photographs could activate the world through coincidence, gesture, and good light. When I rediscovered those negatives I was also delighted by how photographs can express the passage of time, and make antique a world that was the world just a few years before. This whole process began for me shortly after a fellow former-cadet passed away while in the service, so the project was also tinged with this melancholy as I realized how lucky I was to get out.

I think the project is past me for the most part. I can’t imagine digging it up again. I’m so far past ROTC that I’m not sure how to reckon with it anymore. Those photographs might as well have been taken by another person altogether. But, idk. It’s a good lesson for me. It helps me to recognize the plurality of the self.

Images from Following Seas, 2010 & 2015

KHB: In your early work (Zazen and Before I Go), there is a thread of spirituality that runs through the images, exploring death and decay alongside desire and love. Does this still infuse the way you make your work, several years on? How do you see this nascent work interact with your current work, like Paralytic States and New Bodies?

KS: Oh, it absolutely does. For the longest time photography has been a deeply spiritual practice for me. It can, at times, be a meditative tool. A tool for healing and engagement. A tool for observation, contemplation, and greater understanding. It’s often about death, life, and the reciprocity of both. At times I’ve run away from the spiritual, and at times I’ve embraced it. Wrestled with its implications, with doubt and depression.

Of those projects, Zazen was probably the most consciously spiritual, since it involved the use of photography as a tool in my contemplative practice. Before I Go carries some of those spiritual themes, but I think, also rails against them. I made that work when I knew I was closeted (post-egg), wrestling with identity, the ego, and with a spiritual practice that I had previously employed in a desperate attempt to extinguish the latent queerness of my deeper self. I was bitter about spirituality since I saw it as one of many things I had used to avoid accepting myself.

Maybe Paralytic States is a bit more agnostic, but through it, I’ve come around to a more expansive (mature?) understanding of what spirituality can look at. When I started making that work I was softening my position on spirituality, and returning to photography as a cornerstone of my practice.

As to New-Bodies, it’s still such a new project. Maybe just a continuation of Paralytic States? I’m not sure what it's doing yet, other than motivating me to continue experimentation. But I do think it retains the spiritual, in the sense that I find myself interested lately in interrogating the recent profusion of apocalyptic narratives in art, media, and culture. I’ve said in that work that “I don’t think the world is ending”, and I guess I’m still trying to figure out why. Maybe because spiritual practice teaches me that the end of old things usually gives way to the birth of new possibilities? I feel optimistic in that way.

The Lover At Night, from Before I Go