Q&A: jess t. dugan

By Hamidah Glasgow | September 27, 2018

Jess T. Dugan is an artist whose work explores issues of identity, gender, sexuality, and community. She holds a BFA in Photography from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, a Master of Liberal Arts in Museum Studies from Harvard University, and an MFA in Photography from Columbia College Chicago. Her work has been widely exhibited at venues including the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the San Diego Museum of Art; the Aperture Foundation, New York; the Transformer Station, Cleveland; and the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago. Her first monograph, Every Breath We Drew, was published in 2015 by Daylight Books. The same year, she was the recipient of a Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant and was selected by the White House as an LGBT artist Champion of Change. Her second book, To Survive on This Shore, was published by Kehrer Verlag in 2018. She is represented by the Catherine Edelman Gallery in Chicago, IL.

Hamidah Glasgow: Tell me about To Survive on This Shore. How did it begin and what was your process for working on it?

Jess T. Dugan: Prior to beginning To Survive on This Shore, I had been making portraits about gender, identity, and sexuality for a long time, often working within LGBTQ communities. I had worked more extensively within transmasculine communities and around issues of masculinity in projects such as Transcendence and Every Breath We Drew. I met my partner, Vanessa Fabbre, in 2012. She is a social worker and researcher whose work focuses on the intersection of LGBTQ communities and aging. She had worked within transgender and gender nonconforming communities previously on her research and dissertation, although she had focused more on transfeminine communities. We realized that, despite being in different fields, we had overlapping interests and we decided to begin this project together. She brought the element of aging and I brought the element of photography; I made the portraits and Vanessa created the accompanying texts.

Dee Dee Ngozi, 55, Atlanta, GA, 2016

We made the first portraits and interviews in the summer of 2013, and we began with people we knew. The project quickly grew through word of mouth, and by early 2015 we had made about 25 portraits. At that time, I created a website and we got a flurry of press, including a feature in the New York Times, after which I received over 100 e-mails from people all over the country wanting to participate. Between 2015 and 2018 I worked on this project intensely, and we ultimately created 86 portraits and interviews with people throughout the United States. From the beginning, we were committed to diversity and sought subjects whose lived experiences exist within the complex intersections of gender identity, age, race, ethnicity, sexuality, socioeconomic class, and geographic location. It was important to travel to each person and spend time with them in their home or personal space, which is partially why the project took so many years to complete.

In addition to word of mouth, I attended several trans conferences to present the work and meet subjects. I also reached out to LGBTQ nonprofit organizations while I was traveling and collaborated with them on finding local subjects. Last, there were certain people within the community who I knew I wanted to include because they were leaders or activists.

The project was recently published as a hardcover book by Kehrer Verlag. It includes 65 portraits and interviews as well as an interview with Karen Irvine, Chief Curator and Deputy Director at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, IL. I also recently opened a solo exhibition of the work at projects+gallery in St. Louis, MO which will travel to several museum venues beginning in 2019.

To Survive on This Shore, projects+gallery, St. Louis, MO, 2018

HG: This project is taking on a life of its own as the media and the public embrace the work. How do you see this work affecting societies evolution of inclusiveness?

JTD: It really is. It is wonderful to see. Over the five years we spent working on it, we were hoping for this moment when we would release the project into the world and people would take it and use it for their own education and advocacy. I am often asked if I’m still working on the project; we certainly could have kept going, as I had interest from significantly more people than I could ever have included. While the making of the project is complete and I don’t plan to continue photographing for it, in some ways, its life has just begun. I feel like we’re entering “Phase 2,” when the work can really begin to make an impact.

The media attention has been wonderful, not just for me as an artist, but because it really makes the work accessible on a large platform and allows it to reach the people who need to see it the most. In the past month, it has been featured in the New York Times, CNN, The Guardian, The New York Journal of Books, Photo District News, Photograph Magazine, Buzzfeed, HuffPost, The Advocate, and many other outlets. The response has been even larger than I anticipated it would be, which points to a demand for this work.

Panel discussion at the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, IL, 2017

HG: How do these portraits with accompanying stories help all of us broaden our understanding of the spectrum of gender and queerness?

JTD: One of the reasons we began the project is that we were aware that there was a serious lack of representations of transgender people – particularly outside of Hollywood or violence-oriented media reporting – but especially of transgender older adults. We created this project to fill that gap, and we hoped it would validate the experience of transgender older adults, many of whom are directly responsible from the progress we benefit from today, and also act as inspiration for younger transgender people. Prior to beginning the project, we heard from several younger trans folks that they had never seen an image of an older transgender person and had no road map for what their lives might look like as they grew older.

The aging element has, in many ways, made the project even more universally accessible while also maintaining the specificity of the stories of the subjects included. Many of the interviews center around the idea of wanting to live authentically and grappling with the risks, as well as the benefits, of doing so, particularly later in life. This is an idea everyone can relate to and understand, whether they are trans or not. We all want to live as ourselves and be supported and loved for it.

SueZie and Cheryl with their copy of the book

We also wanted to push back on the idea that a trans identity is a new thing or something that was created by today’s young folks. Trans people have always been here in a wide variety of manifestations and identities. The language we use to talk about it has changed, as has the awareness and understanding of trans identities within society, but the identity itself is not new. We intentionally sought older adults who identified as either genderqueer or nonbinary as well, as these identities in particular are sometimes associated with youth culture.

We also wanted to push back against the idea of aging as a decline. Many of the subjects in our project transitioned in their 70s or 80s, and even those who transitioned younger were still evolving and growing and taking on new and ambitious projects as they aged. We wanted to enforce the idea that it is never too late to be who you really are.

I was humbled by how open each person was with us. For most participants, we had never met in person prior to us showing up at their house to interview and photograph them. We were welcomed wholeheartedly, and people shared their most difficult – as well as their most joyful – life stories with us. Many people wanted to share their stories in an effort to help others who came behind them; they wanted to be the role model they wished they’d had.

HG: I would like to hear more about pushing back on aging. We are a youth-centered culture, especially so in the queer world. A lot of work I see that addresses aging actually reinforces youth culture. The subjects in To Survive on This Shore shows people in their element, comfortable with who they are. This embrace of the power and ease that accompanies aging is vital to flip the script. Tell me more about your approach to the pushback and perhaps advice to others taking on work in this vein.

JTD: I absolutely agree. As you mention, our culture as a whole is youth-focused, and this can be even more intense within LGBTQ communities. Recently, there has been a lot of attention on trans youth, which is wonderful, but of course it is only one segment of the community. I felt that it was important to focus on the older members of our community because their stories are important and are also at risk of being lost. I hope that it is meaningful for younger trans folks to see a wide array of options for what it looks like to be a transgender or gender nonconforming older adult.

We are also entering a time when a larger number of out LGBTQ adults are aging publicly than ever before, and they are thinking about things like accessing healthcare later in life and seeking affirming care in assisted living facilities and nursing homes. Unfortunately, we have a long way to go in this regard, and there is still a large amount of discrimination against LGBTQ older adults. Recently in Missouri, a lesbian couple was denied housing in a senior living community, the Friendship Village of Sunset Hills, and have filed a lawsuit against them in the U.S. District Court.

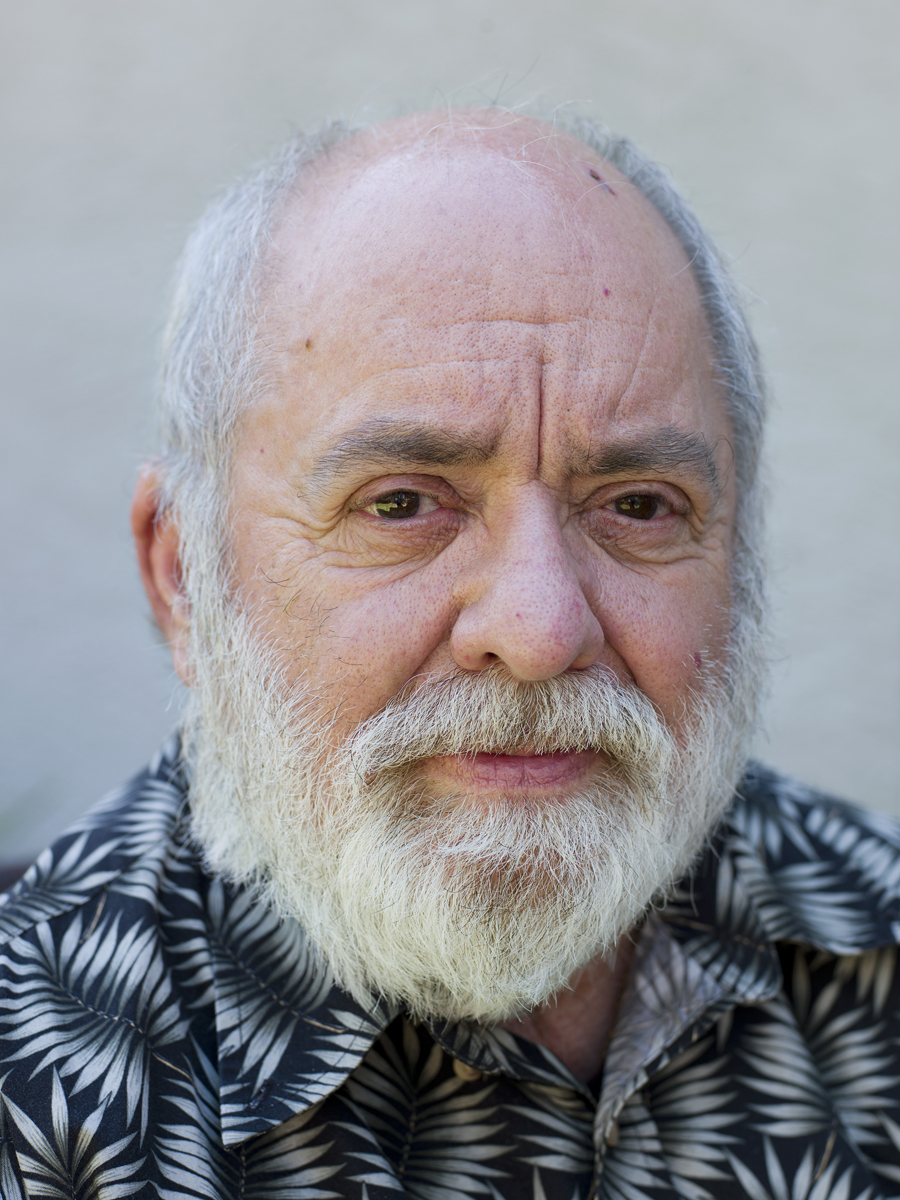

Jay, 59, New York, NY, 2015

One of the subjects in our book, Jay, spoke about horrible abuse that he and his partner experienced in a nursing home, as well as discrimination he experienced from doctors surrounding his breast cancer diagnosis. He passed away one year after we made his portrait, and in my mind, he died as a direct result of discrimination:

My partner, Eleanor, was a big time activist. She was one of the most outspoken people in our community. But she had a huge stroke when she was fifty-six and from there on I was either taking care of her or she was in a nursing home where she was horribly abused. I mean, horribly abused. Eleanor had bedsores from lack of care and neglect at the nursing home and this woman would come in and take this rag and wipe between Eleanor’s legs while screaming at her, “This is for Joy, isn’t it? This is for Joy. You’re going to hell! You should repent or you are going to hell when you die. You’re going to burn in hell, you pervert.” Joy is my previous name and how the nursing home knew me. So that is what they inflicted on her, they basically rubbed the bacteria from her anus and genital area into her bedsores.

Then I got cancer and I was facing discrimination where doctors wouldn’t even give me my biopsy results. The man who was supposed to be my breast surgeon wanted to send me out to psychiatry. Wanted to send me to psychiatry before giving me any breast cancer care! And he didn’t even call me to give me my biopsy results. I didn’t even know that I was sick for a long time.

It is my hope that this project can help to educate providers working with older LGBTQ adults and lead to more education and understanding across the board. In terms of others doing this work, one organization doing fantastic work with LGBTQ older adults is SAGE: Advocacy and Services for LGBT Elders.

And, as you mention, there is also a freedom in aging. Several people spoke about how their transitions were actually easier because, as an aging woman, for example, they were much more invisible to society at large. This is depressing in terms of what it says about society’s sexualization of women, but it is interesting to think about in this context. I also love this bit from Lee Anne’s quote:

I also find that I’ve become more empowered the older I get. You know those little memes on Facebook about the old people not giving a damn? Well, that’s basically how I am, “Accept me or get out of my way.”

Lee Anne, 64, McClellanville, SC, 2016

HG: The project has many iterations, including a book, a museum exhibition, a community exhibition, placement in archives, a limited-edition portfolio, and scholarly journal articles. What is the function of each of these versions of the project?

JTD: From the beginning, this project had an educational and activist mission as well as being a fine art project. We always conceived of it as a book and exhibition, both of which would include the portraits and their corresponding quotes. However, while a book is more accessible than an exhibition, it is still only one vehicle for getting the work out into the world. We wanted this project to reach as many people as possible and to be used in different ways and contexts.

For the exhibition, there is a traveling version available to art museums, but as you know, traveling an exhibition is costly and also comes with certain logistical requirements, such as climate control, insurance, etc. We are also in the process of creating a community exhibition of this work that will be smaller, more affordable, and made available to community centers, nonprofit organizations, nursing homes, senior centers, and other places outside of an art context where the work needs to be seen.

I also created a limited-edition portfolio that includes 12 portraits and interviews designed specifically for college, university, and teaching art museums. This portfolio operates as both a ready-made exhibition and an educational tool. I am thrilled that since its creation in January 2018, the portfolio has been acquired by Light Work at Syracuse University, the Smith College Museum of Art, and the Tang Museum at Skidmore College. All three venues have already exhibited the work, which points to its relevance and necessity.

Installation view of the portfolio at the Tang Teaching Museum at Skidmore College, 2018

While creating the project, we realized that we were generating a massive amount of oral history, as the interviews were usually an hour or longer and generated between 20 and 25 pages of transcribed text. For the book and exhibition, we edited that down to 2 or 3 paragraphs per person, so a lot of the full history was being lost. We decided to donate the project in its entirety, including full interview transcriptions, to several archives to be preserved for future study. The archives currently on board to accept the project are the Sexual Minorities Archive in Holyoke, MA, the Transgender Archives at the University of Victoria, and the Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction at Indiana University. We are open to any additional archives who are interested in the project.

Last, Vanessa is also using information from the interviews in her research and will be writing several scholarly journal articles about them in the next several years. We want the work to be distributed through as many different avenues as possible to have the largest effect it can.

Advocacy poster created in collaboration with openhouse

HG: You are collaborating with several nonprofit organizations to use the work in education and advocacy campaigns as well. Tell me more about that.

JTD: Yes, absolutely. We are very open to collaborating with any organization who can benefit from the work and have been receiving an increasing amount of requests to do so as the project has gotten more and more attention.

For example, we have already collaborated with The LGBT Aging Project in Boston, MA, who is using work from the project to develop a training module aimed at older adults who might encounter transgender and gender nonconforming peers in nursing homes and senior centers. We also collaborated with an organization called openhouse in San Francisco, CA, who created an advocacy campaign using the photographs to protest the removal of a question about gender and sexuality on the National Survey of Older Americans. In 2017, the work was exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, IL, and the museum organized a simultaneous exhibition at The Center on Halsted, Chicago’s LGBTQ community center. We welcome any future collaborations where the work can be put to good use.

To Survive on This Shore, The Center on Halsted, organized by the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, IL, 2017