Q&A: holly lynton

By Jess T. Dugan | May 5, 2022

Holly Lynton (American, b. 1972) is an artist living in Western Massachusetts. Her photographs explore the intersection of faith, history, and the environment. Holly was a 2021 Critical Mass Top 50 finalist and is the recipient of an Aaron Siskind Individual Photographer’s Fellowship, a Massachusetts Cultural Council Fellowship, and the Syngenta Photography Award. Yale University awarded her a postdoctoral research fellowship in 2019 at the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition for her series Under the Brush Arbor, Methodist camp meetings in South Carolina. Her work has been featured in publications such as The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Boston Globe, The Miami Herald, Southern Cultures, and Harvard Design Magazine. Recent exhibitions include On the Basis of Art, 150 Years of Women at Yale (2021), at the Yale University Art Gallery, and a solo exhibition in collaboration with Maurice Wallace: Meeting Tonight: Two South Carolina African American Camp Meetings at the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University (2022).

Jess T. Dugan: Hello Holly! Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me. I’m excited to talk to you about your work, including your project and forthcoming book, Bare Handed. Before we jump in, could you tell me about your background? What originally drew you to photography, and what was your path to getting to where you are today?

Holly Lynton: Hello Jess! Thank you so much for this interview and featuring my work on Strange Fire Collective. I’m excited to be here and chatting with you. It’s great to have the opportunity to share some aspects of my practice.

I am happy to share my background and what led me to photography. I grew up in both Colorado and New York City; I began flying solo between the two places at age five after my parents divorced. Throughout my childhood, both of my parents also moved many times. I lived in the city, the suburbs, the mountains, and small towns. As an only child, I always ended up chatting with the people I sat next to on those planes. They constantly asked me the same question: which place did I prefer? I remember feeling puzzled back then about why an adult wouldn’t realize that there could be good things about many places and how could they ask me to choose between my two homes, both of which I loved. I realized later that was a key moment to my never-ending desire to show the connections between disparate places or ideas.

Originally, my plan was to be a writer—a novelist—and psychologist. I didn’t have any access to photography until I went to Yale as an undergraduate. My stepfather was a cinemaphotographer, and he obsessively documented my life in still photographs (always 35 mm chrome film) and in video, so I was used to constant observation. Yet, I rarely saw the results because he didn’t put on slide shows. A childhood friend of mine was able to take photography in high school in Boulder, and I remember marveling over her beautiful silver gelatin prints, which made me want to make them too. So I signed up for Lois Conner’s “Intro to Photography” course, and Dawoud Bey was her teaching assistant at the time. They were an inspiring duo in the way they talked about photographs, and that class initiated my love of photography. Creating an ambiguous narrative within a single, still image was a challenge I fully embraced after years of writing short stories. During a semester abroad in Italy and at the Aegean Center for Fine Arts in Greece, I studied art history and learned to watercolor, which taught me to see color. Yale photo at the time required that undergraduates photograph entirely in black and white film. Back at Yale, I completed my psychology major and continued writing stories, while also studying photography and art history. My background in psychology is still an aspect that features in my work today. After my undergraduate degree, I interned at Aperture and worked as a photo editor at several publications prior to attending Bard College for an MFA. Following graduate school, I worked other jobs—as a research associate conducting studies in alternative and complimentary medicine and as a yoga teacher—while also having two children. Eventually we moved to London, and then rural Massachusetts, which allowed me more freedom to work as an artist and raise my children while doing that. It was also important to me to live a more sustainable lifestyle, support the local farmers in my area, and that my children develop their own imaginations and creativity while exploring the woods out their back door.

Sienna, Turkey Madonna, Shutesbury, Massachusetts, 2010

JTD: Tell me about Bare Handed. What is this project and how did it come to be?

HL: Bare Handed started in 2007. At the time, I was living in Weehawken, New Jersey and completing my series Solid Ground, which was made entirely in my small, semi-urban backyard. One picture depicts a bird trapped in raspberry netting, which was a recreation of an event I witnessed. For me, often a small occurrence can spark an idea for a new body of work. Watching the bird escape the netting—the netting I had placed there so I might eat the raspberries—caused me to reflect on our food sources and the mark they leave on the environment. At the same time, many artists like Andreas Gursky and Chris Jordan, with his Mass Consumption and Albatross series, were exposing the harmful effects our food systems and waste were having on the environment. I believed there had to be people working in another way. In addition, West Nile virus was a concern, and the pervasive message in the media was “even our backyards were dangerous.” All these inputs started me searching for people who allowed for a vulnerability when facing nature. I began looking for a beekeeper to photograph. Of course, even within the world of beekeeping there are more sustainable and creature-friendly practices and more large-scale, commercial enterprises that don’t consider the health of the bees. I photographed a couple of people in rural England—because we were living in London—but they wore the full protective gear and that wasn’t what I had in mind. Through a combination of word-of-mouth, my having an exhibition in New Mexico, and the serendipity of a fallen tree with a feral beehive, I found Les Crowder. I returned to the U.S. to spend a few days with him and made those first pictures in the series: Les, Amber, Honeybees, the Bosque, New Mexico and Les, Honeybees, the Bosque, New Mexico. While I was visiting friends there, I asked for other ideas and was directed to the wolf sanctuary where I made Angel, Wolf, Ramah, New Mexico.

Les, Honeybees, the Bosque, New Mexico, 2007

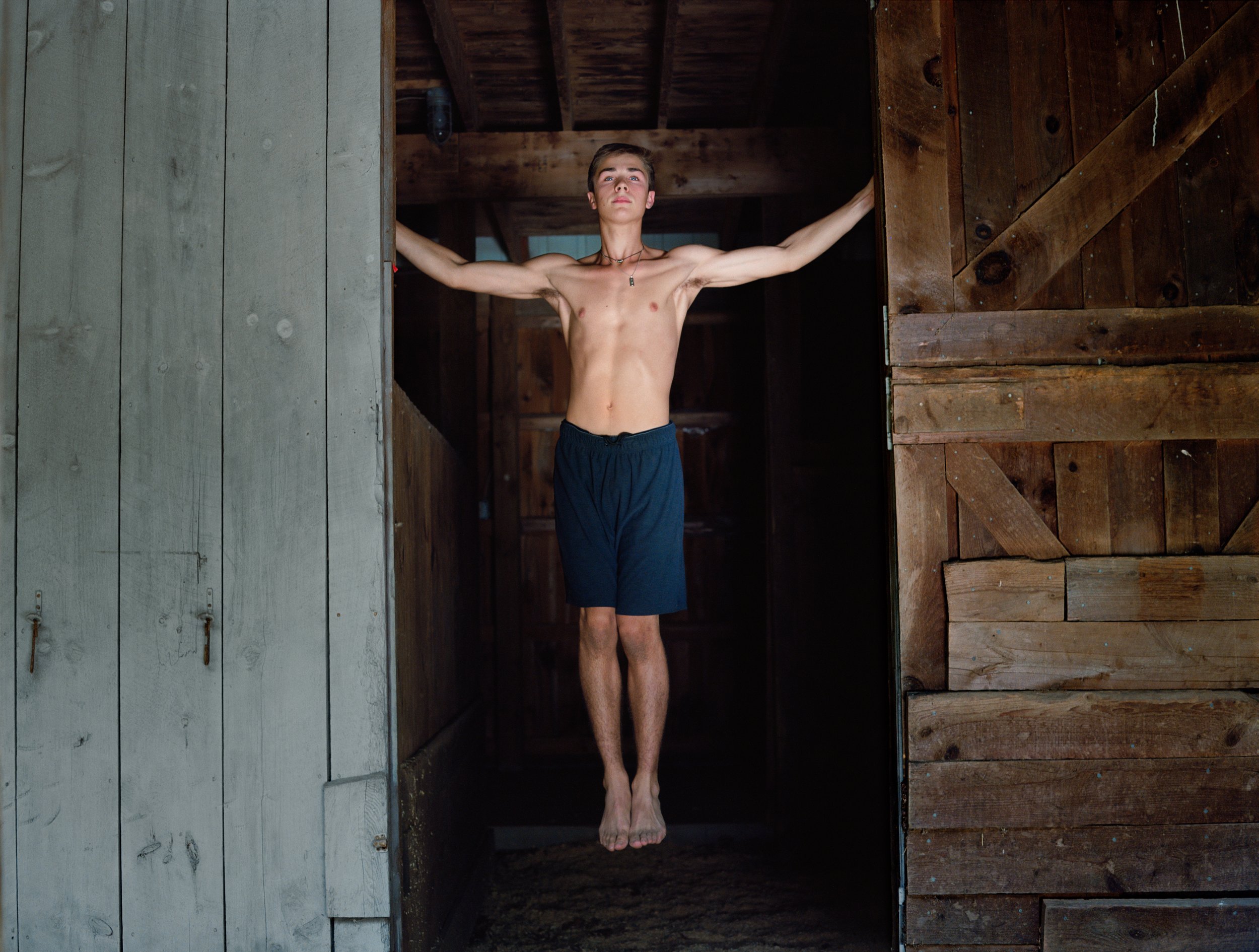

Formally, I’m interested in how the human body relates to the natural world, and to the geometry of the structures we build. I danced ballet as a child, and then did aerial swing dancing and flying trapeze as an adult. The exhilaration of flying through the air is pure freedom to me. I’m constantly interested in gesture and movement and photographing people as they move. There is ambiguity in the gestures that I hope provoke an investigation of all the possible narratives. When I am photographing, I watch their movement for hours to capture the quintessential gesture at the right moment.

The pictures are not meant to be photo documentary, so I often spend many days with each person when making the photograph, hoping for magic to happen. I draw on mythical tales and try to imbue a fantastical element, though they are also made from authentic moments.

I feel most anxious while photographing during the minute it takes to reload film. I fear that the person I am photographing will keep moving and perform the awaited action, or align with the light in the perfect movement, and I will not have the film ready in the camera to capture it. Furthermore, there is a conflict between the speed of photographing and the necessary research and planning that has become a part of my process and work. While my photographs are made in fractions of seconds, the other work can take months or years to develop.

JTD: You write about being interested in the human connection to the land and nature as well as an interest in vanishing industries, particularly around sustainable living, and farming. And, you also address an element of spirituality in your work and in the people you photograph. How do these elements intersect for you?

HL: The intersection of spirituality, history, and the environment is a crossroads that I feel I could explore photographically for the rest of my lifetime, because there are so many different aspects to it. Spirituality to me is also an individualized experience. There is a spiritual practice in agriculture and fishing, as farmers and fishermen give themselves over to that which they cannot control. Releasing power and acceptance are part of many spiritual practices and traditions, not limited to but of course including many religions. The people I photograph who are passionate about working the land with methods that embrace the idea of being good stewards of it often exhibit a tenacity that goes beyond the rational and is a form of faith. It defies logic in the sense that often there is little economic benefit. There may be enough to sustain them and their families, but it does not often go beyond that. So, drawing on my psychological background and eternal curiosity, I often wonder, “What motivates them to persevere?” One of the reasons I strive to create visceral images that convey as best I can what it felt like to be there is that often that physical experience points to a form of a spiritual experience. The declining industry of shrimping in South Carolina for example—shrimp caught there are only sold locally—is more than just shrimping. It is the experience of being at sea with the seagulls, the dolphins, perhaps witnessing a thunderstorm from the boat at 2 a.m. These are all spiritual experiences that extend beyond words and reinforce how humans are a small part of the entire ecosystem of this planet. As I photograph, witness, and experience, I find there are meditative qualities to the work and a letting go that occurs. Of course, some environmentalists may criticize any fishing practice, and the bycatch that is discarded, which includes sharks caught up in nets. My goal is not to judge but to present the range of humanity. I have also photographed weir fishing in Massachusetts, which is the most environmentally friendly form of fishing and naturally the most labor intensive. The first time I went out with the weir fishers, it was a dense fog. While we were only a few miles offshore, I reflected that if I were alone (without their navigation skills and knowledge) I would be quite literally lost at sea. It is those moments when you feel small in the face of the power of nature that are a kind of spiritual practice for me, and I think motivate the people who work in this way to persist as well, despite economic hardship and sheer exhaustion. There is a commitment to something greater than themselves.

Lift, Hadley, Massachusetts, 2010

JTD: Many of the photographs in this project feature farms and communities in rural Massachusetts, where you live, but others are in different places, as you mentioned, such as Montana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and South Carolina. How did your pictures—and your experience making them—change in different places?

HL: The early pictures in Bare Handed focused on finding specific people working in a way that honored the land and left little mark, and also on the dichotomy of danger and surrender. Whenever I begin a series, I start with a question or observation and set about to see what other people think about the idea. Besides photographing Les, the beekeeper, and at the wolf sanctuary, I photographed catfish noodlers in Oklahoma. When making the images in Oklahoma, my assistant was walking along the banks of the lake and the mayflies swarmed around him. He was quite disconcerted but surrendered to the moment. The resulting image Stephen, Mayflies, Temple, Oklahoma was a transition point for me as I realized that this quality of surrender need not be determined by the situation being inherently dangerous or life threatening. Later, I learned that adult mayflies only live for one day, sometimes only hours, and yet mayflies are incredibly important to the ecosystem of freshwater life, as they filter water and are a source of food. Their prevalence or decline also indicates the health or pollution of water bodies. For example, in the late 1950s, scientists began tracking the mayfly population of Lake Erie as an indicator of pollution levels. Can you imagine the humility of a creature that only lives for one day? How precious, then, is that day. Mind boggling, and so potent. I then began to research allusions to mayflies in other artworks, and not surprisingly there are many.

Stephen, Mayflies, Temple, Oklahoma, 2009

That same summer in 2008, I moved to rural Massachusetts. My goal to live more sustainably and support local farmers enabled me to become even more acutely aware of the quality of surrender that is inherent in agriculture. Farmers surrender to the power of nature—what the land yields is beyond their control—especially now with climate change. In my fourteen years living here, I have seen a steady decline in snowfall. Initially, we could count on several feet covering the land for months at a time, whereas now we are lucky to get one snowfall large enough that we might go sledding. I began photographing the farmers in my community and the transitions that were taking place in the environment.

After a visit to the Lowcountry, South Carolina, I realized that while the two environments of Massachusetts and South Carolina were different, there was much connection as well, and many people there were working with a similar passion for environmental concerns. Each place has its own complicated mix of history and current industry, determined by the geography. Naturally, the food systems in South Carolina are different from Massachusetts and yet again from Montana, as is the history. Photographically that geography and history affects where and how I photograph, also the light in each place is unique. My motivation in expanding the project to other geographical areas was to show the common humanity that exists in various rural communities in the U.S., which has become even more important now as we all too often seem to fixate on difference.

I always like to think of specifics, and experiences we all share, like buying groceries. In Massachusetts it takes twenty minutes to drive to the grocery store. In Montana, it can take an hour or more. In New York City, it might take 30 seconds but then it all has to be carried or delivered. There is variation in the shared experience, which is what makes things complicated and beautiful and interesting at the same time.

Bare Handed, cover, slipcase design

JTD: Tell me about the book. How did it come to be, when will it be released, and what do you hope its effect will be? Does the publication of Bare Handed signal an end to the project or do you plan to keep working on it?

HL: Several years ago, it was suggested to me that I make a book of the Bare Handed series, but at the time the series was too much in progress to warrant one. Finally, many years later I felt ready, and yet grappled with how to transform the project into a book. I was gearing up to do that before the pandemic, and then everything was halted. However, the break allowed me time to consider how the book could stand apart from the images that are in an exhibition. As I worked on sequencing, I found that I was able to pull in images I had created but never shown that spoke to the environments where the photographs are made—all the different trees—and even the weather. There is attention to darkness and light in the book. I worked with a wonderful designer, Margaret Bauer. She helped me with the final sequence and created an experience that begins with the slipcase, which is a detail of an image I made in the summer of 2020 of a silo covered in vines. At the time, it reminded me of how we all felt in quarantine and highlighted how nature will always reclaim human structures that are abandoned. Now, it serves as a layer you quite literally need to pull off to experience the photographs. I appreciate how Margaret incorporated the idea of layers into the physical design of the book. The added time also allowed me to ask two art historians to write essay contributions for the book: Terence Washington and Carl Fuldner. There is a poetry contribution from Victoria Chang, from her newly published book: The Trees Witness Everything, and her poem is in conversation with Terence’s essay. Then, finally, my publisher suggested that my daughter, Madeline Poole, write an original poem for the book, which she did in response to six of my photographs. It is always important to me that I bring in different perspectives when putting the work into the world, that it isn’t only my voice. Ultimately, the book moved beyond what I dreamed it would be at the start. For its effect, I hope it will broaden awareness of the project.

I think this publication does signal the end to the series, although there are images in the book that also live in Ten Thousand Haystacks and Beyond the Bounds. One series often leads to the next so there is a transition of images. Of course, then there are images that are only distinctly in one. I make rules for myself and then break them!

In a sense, I could continue Bare Handed by exploring many more rural communities in the U.S. and looking for what traditions and practices are still happening there, what rituals are tied to history, and what is new. However, at this point I prefer to explore any microcosms I discover as their own series, and much like when I was a kid, the communities I have become close to I visit every year to see people and photograph. For me it is more about going deep, than wide. I make better photographs when I know people and spend time with them year after year. The photographs are also my expression of love and appreciation.

JTD: As you mentioned, you’ve been working on this project for more than a decade, so in some ways it preceded the current moment we’re in around climate change, when concern and dialogue have increased in both the art world and society more broadly. How would you articulate your work’s relationship to climate change? Has this evolved over the past decade? Do you view your work as activism?

HL: This is a great question. I have noticed a shift in the reaction to the work recently. It seems it is striking a particular chord now, although I am not sure I can articulate why that is as the maker of it. When I expanded the project to include people working in agriculture beginning in 2008, the conversation around sustainability was centered on organic farming or “green” living. During the recession of 2008 and the years immediately after, it was one area where people were investing. My husband was unemployed three summers in a row back then and surprisingly it was the companies aligned with “natural and organic brands” that provided some income. Perhaps people were holding onto an idealistic belief that small changes like buying organic would be enough. However, when it comes to sustainability it is a much bigger conversation than that—something I think we are now all acutely aware of, especially in rural America. When I started Bare Handed, I was naïve in thinking I could focus on small, local farmers and address sustainability when it extends to subjects like depopulation of rural areas and how that depopulation affects the quality of our rural public schools. With a declining tax base, depopulation forces budget cuts and then of course an influx into the cities affects schools because of overcrowding. The local, small dairy farms have literally been replaced by big box stores, yet people still drink milk. In the last few years, I have begun a project with ranchers in Montana who work in a way that respects the land, yet the demands of marbleized beef in expensive restaurants in faraway cities like Chicago determine that many of their cattle (who start life grazing on native grasses and forest land) are sold to feed lots. One rancher raises a small percentage of his cows organically each year, which he does at an economic loss, and sells them locally in Montana. Many of these ranchers wouldn’t eat their own cattle once they leave the ranch. For the most part, people who are committed to more healthy practices can only afford to sell locally and sometimes only directly from the farm in a CSA model. My work focuses on portraying people over time, yet the pictures themselves may not convey these details. They are not meant to be didactic. I suppose it is in the dialogue about the work that I can begin to share these details and often the hypocrisy we must face to really begin to solve some of the issues around climate change, with the hope that it is not too late.

Because my work is made over time, it highlights change and a connection to history. Examining the history of how we got here is also important, and as an artist it is an aspect of my work that I have grown into in terms of how to portray it, understand it, honor it—it’s an ongoing dialogue. I think this is all something we’ve also become more aware of on a larger scale in the last two years. In each community I photograph, the violent history of the U.S. is present, and I want that history to be reflected or a part of the work, while also considering what is happening now and changing in these communities today. For instance, in re-introducing indigo as a crop—even on a small scale—we need to consider what is the history of indigo, what does it mean to grow it now, and what about blue jeans? All is interconnected – it’s a question of how far any one individual wants to take the connections. Ultimately, many of my images point to transition.

An industry that sustained the Connecticut River Valley for a long time was cigar tobacco, specifically cigar wrappers. Now, many barns have been torn down and the farmhouses too; however, the fields are being leased for other crops, like potatoes. Initially, I felt the images I made in tobacco barns did not fit the series, when focused on this idea of green living, but then I realized they did when my own view of sustainability shifted. I also think it’s important to admit we don’t know everything but rather to approach topics with a willingness to learn and change perspective. Every photographic endeavor for me is a learning experience as I try to understand the perspective of the people I photograph and expand my community.

Now that smoke from the west blankets the Massachusetts skies for a few days each summer, people are talking about climate in a new way. Yet it’s different still to experience it first-hand. The Montana ranchers I photograph have had to help the Forest Service put out fires in the morning then resume haying in the afternoon. There is a concern that people in big city centers far away are making decisions about their livelihood and the environment without having ever been there to see what it is actually like.

People may look at my work and not see the direct link to climate change, but then I think we all like to believe that we are making choices that are healthy for our planet, but there are probably many areas we still need to consider. Once, when I described many of the actions depicted in my photographs as “every day,” one of my gallery dealers said, “well that’s not most people’s every day.” So, my response is, “why not?” And perhaps it should be. Or at least an awareness of where our food comes from, how our country’s history has determined our agricultural systems, who gets to work the land, and who must work the land. Beyond that we need to consider our relationship to and opinions of manual labor and the drive towards mechanization and efficiency. But at what cost? What amount is enough? What do we really need? And circling back to the spiritual aspect, what really feeds our soul? Are we moving too fast to consider the weather?

Initially, I did not consider my work as activism because I was not telling people directly what they should think, although I hoped that by presenting alternatives or sharing the work of people in my photographs that I would encourage new perspectives to be seen. I hoped that the work would inspire questions and then any viewer would do the work to understand. Perhaps that is a form of activism after all.

Methodist Church, Bannack, Montana, 2018

JTD: I’m also interested in your projects Under the Brush Arbor and Beyond the Bounds. Could you tell me a bit about these projects and how they came to be, and perhaps expand on how they relate to, or extend, your work in Bare Handed?

HL: All of my projects begin with a series of questions—usually a challenge to myself and a question about humanity. With Solid Ground, I challenged myself to explore my own banal, semi-urban backyard as if I were on safari and hoped to find a sense of wonder there in my everyday environment. There is always discovery along the way; the questions and my own ideas of what the work is about changes too. For that reason, I’m often hesitant to delve too deeply into describing new work or what it will yield as the journey is so much a part of the process. However, my current projects definitely have seeds in Bare Handed.

Like Bare Handed, Beyond the Bounds will be created all over the U.S. The title Beyond the Bounds comes from the Wendell Berry poem: “Homecoming”:

“…in that wilderness, we roam

the distances of our faith,

safe beyond the bounds

of what we know.”

It is an exploration of what faith means to Americans today, both in religious contexts and beyond. Like Bare Handed, it is evolving from a variety of inputs: experiences with friends, my own spiritual practice, and news articles. Religion can be polarizing, yet somehow faith is not. I have been reflecting on gestures of worship and the unity in that embodiment. When I was beginning this project, a friend of mine died in a car accident—a teacher on his way to school, hit by a truck driven by a sixteen-year-old who skidded on black ice. The next day, I allowed my sixteen-year-old to drive her thirteen-year-old brother to school, in what I can only attribute to faith. Faith that they would return. The cyclical and intertwined nature of these acts allowed me to consider how faith permeates our lives daily, in our subconscious, in ways not often considered. That is the aspect I want to delve into in photographs. What that will look like, time will tell.

To make these portraits, I collaborate with people by asking them what an embodiment of faith would look like for them. The portrait may reflect an aspect of their existing spiritual practice, or it may reflect a necessary moment before physical activity, like the preparation of the rock climber before he climbs. Each person has a unique personal narrative, which I draw on as we work together to visualize their interior faith. My friend Dontavius was my first willing collaborator. Then the pandemic happened. I also made a portrait with a friend’s son as he embraced a deeper commitment to his Sikh faith after the loss of his father. Another area of interest is the contact improv that dancers engage in, which involves a great deal of faith and trust. But then during the pandemic, no one could touch each other, so I created individual portraits locally with young dancers. I always need to consider, as I make work over many years, what is happening in the world because it necessarily affects what I am photographing. For example, just yesterday I read an article about consent in dance and “intimacy coordinators” in Scotland. It will be interesting to see how the world of dance is now going to change.

Dontavius's Blessings, Rock Hill, SC, 2019

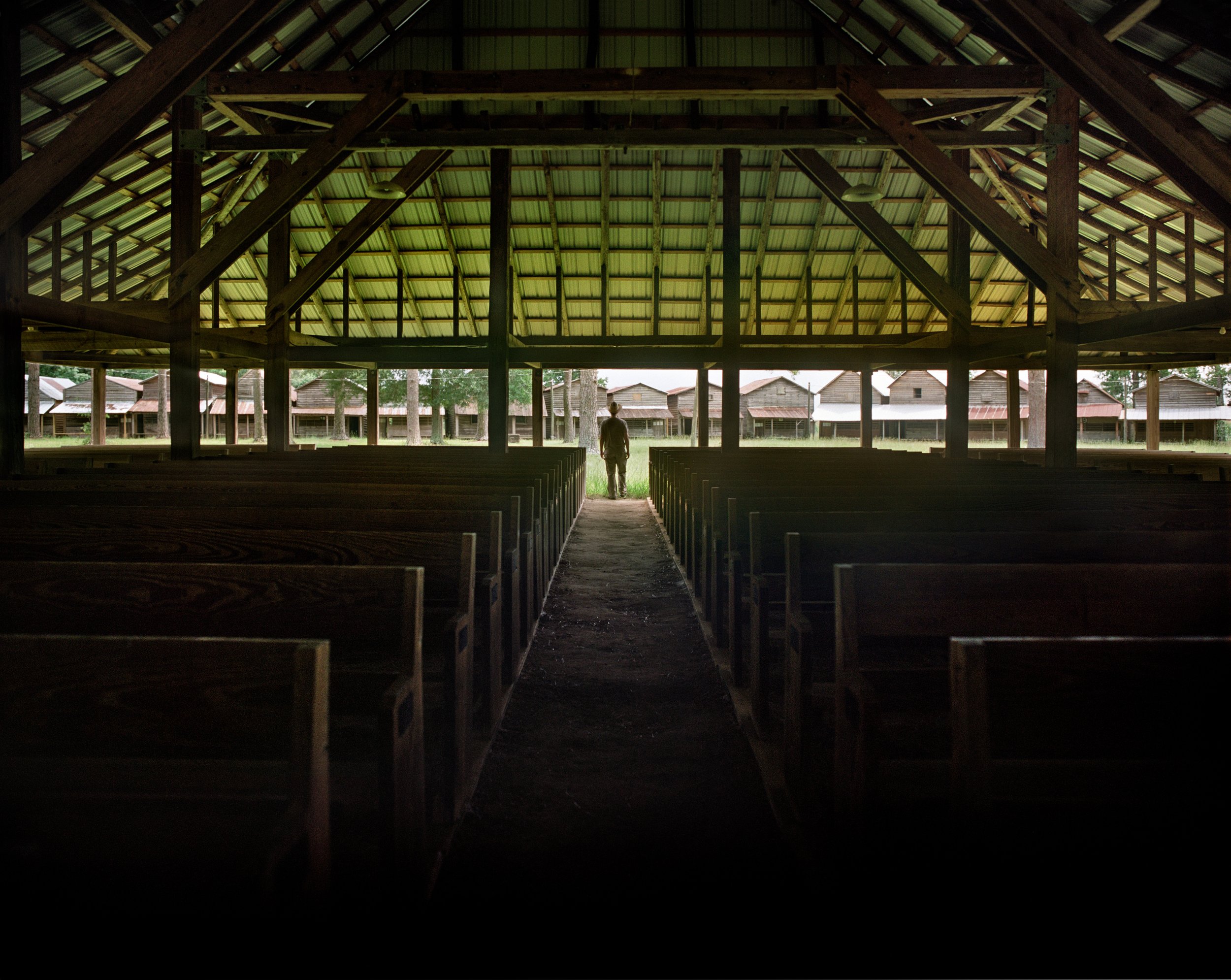

Under the Brush Arbor is a project I began in 2017. The photographs are made at the annual South Carolina camp meetings that began as a part of the Second Great Awakening in approximately 1800. The two African American meetings began in the late 1800’s, around 1870. I learned of the camp meetings from spending time in the Lowcountry and from Glenn Roberts, founder of Anson Mills, and the tradition of the cooking that occurs there. After an eighteen-month process of gaining permission to photograph at one of the meetings, Indian Field, I began visiting every year. During that first year, the minister opened with “we are separated not by race, but by racism…” and that provoked me to research the history, because his words pointed to an ideology that was not reflected in the racially separated camp meetings. In 2019, I was awarded a fellowship at the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale University to study the history of the camp meetings, and I have been visiting archives—local and institutional—to find firsthand narratives about and photographs of the historical meetings to include in the future publication. The camp meetings have been halted during the pandemic for the most part, but I hope they will resume in 2022. This is another project that will likely take me a decade or more to complete because the camp meetings only occur for one week a year. Initially, I knew no one and photographs were made from an uncomfortable distance. Now, I have friends in the community and visit throughout the year. This project is a bit different from the others, though, because the activities at camp meeting are quieter and it is more about relationships and tradition, and transformation. And a sense of place. The visceral quality I am after is important, because the air is thick with smoke from the wood-burning furnaces that are in each “tent” (wood cabins), and the smells and sounds are so much a part of the experience. However, like my other projects, the focus on the spiritual and historical is embedded in this series as well. I am also considering the question of what sacred space is. The first exhibition of the work just opened. Under the Brush Arbor has also led me to photograph historical churches in the communities I visit, to explore the history of Christianity in the U.S.

JTD: In addition to preparing for the release of Bare Handed, what are you currently working on? What’s on the horizon for you as an artist?

HL: After the book is published, I will continue to make photographs for Ten Thousand Haystacks, which I do every August, and Under the Brush Arbor, as well as create portraits for Beyond the Bounds. And even slowly add portraits to Unmasked Relationships, an exploration of sibling relationships I began during 2020 when in quarantine, although it is a challenge to work on so many projects at once. It is also a bit surprising to me after working on one project for so long. I’m excited to be continuing these annual series but also excited to have a period of play and experimentation now that I can focus on Beyond the Bounds more fully.

The pandemic also gave me the opportunity to build community with artists and scholars in new ways, for which I am grateful. Living in a rural area disconnected from the art hubs, it can be hard to build those relationships. But Zoom has certainly helped. Working collaboratively is also something I’ve been bringing into my practice more and something I really enjoy. I am working on a series of letterpress prints as a way to present some of the historical material, and I have another project on the horizon with an art historian in Oklahoma. The first exhibition of photographs from Under the Brush Arbor is a collaborative exhibition with Maurice Wallace. Maurice wrote the introduction text and homilies in response to the photographs. We also have an idea to continue the collaboration to create a book of the project. The exhibition is titled, Meeting Tonight: Two South Carolina African American Camp Meetings; it will be on view at the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers through September 2022.

In reflecting on this question, I realized that my life now is much like it was when I was a kid. Then, I traveled the circuit from New York City to Colorado to San Antonio (where my grandparents lived) each year. I was a chameleon of sorts. In each place, I had different sets of friends and activities. I seem to have recreated something in my photography practice that is similar and my natural way of being. The problem is I keep adding on to the list of places to go each year.

Recently, I was on vacation with my daughter, and I watched as two sisters navigated the Pacific Ocean in a way that only kids who were born in that environment could do so naturally. I struck up a conversation with their mother and we met up a few more times before we headed home. My daughter came away with two young pen pals (who have already written to her) and I left them with a promise to return to make photographs.

Thank you so much, Jess, for giving me the opportunity to share all these thoughts and words.

JTD: Thank you so much, Holly!

All images © Holly Lynton