Q&A: Hannah Altman

By Jess T. Dugan | June 9, 2022

Hannah Altman is a Jewish-American artist from New Jersey. She holds an MFA from Virginia Commonwealth University. Her photographs interpret relationships between gestures, the body, lineage, and interior space. She has recently exhibited with the Virginia Museum of Contemporary Art, Blue Sky Gallery, Filter Photo, and Photoville Festival. Her work has been featured in publications such as Vanity Fair, Carnegie Museum of Art Storyboard, Huffington Post, and British Journal of Photography. She received the 2021 Lensculture Critics' Choice Award and the 2022 first prize for the Portraits Hellerau Photography Award. She has delivered lectures on her work and research across the country, including Yale University and the Society for Photographic Education National Conference. Her first monograph, Kavana, published by Kris Graves Projects, is in the permanent collections of the MoMa Library and the Metropolitan Museum of Art Thomas J Watson Library.

This interview is in collaboration with CENTER and is part of a series featuring the winners of the 2022 Social Award, juried by Jess T. Dugan.

Jess T. Dugan: Hello Hannah! Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me today. We had the pleasure of featuring your work on Strange Fire in 2019, and I’m excited to talk to you again about what you’re working on right now. As a way of beginning, what have the past few years been like for you? How has your work grown and evolved?

Hannah Altman: Thank you so much for selecting me for a CENTER Social Award 2022 honorable mention! It’s such a different reality in front of us from when we last spoke, for obvious reasons. In late 2019, I was in the middle of grad school for my MFA at Virginia Commonwealth University. During this time I was developing a body of work exploring Jewish ritual and objects, often traveling hours to meet and photograph strangers in their homes. This mode of making came to a screeching halt when the pandemic hit. With my thesis semester canceled, I was kind of in free fall, and ended up taking up an offer to house sit a friends’ family beach house in a small town in Rhode Island until things “returned to normal.” I spent nearly two years living on the beach and making photographs in this old, interesting space, and it has shaped my practice so much.

JTD: Wow, that’s so fascinating. I’m always interested in how unexpected life events can significantly change an art practice. In 2019, we talked about your project Kavana, which, as you wrote, “uses Jewish culture, ritual, and folklore as a springboard to narrate photographic stories.” You are currently working on a new series, A Permanent Home in the Mouth of the Sun, that is in some ways a continuation of this earlier work. Can you tell me about the new project and expand upon how it relates to the previous two?

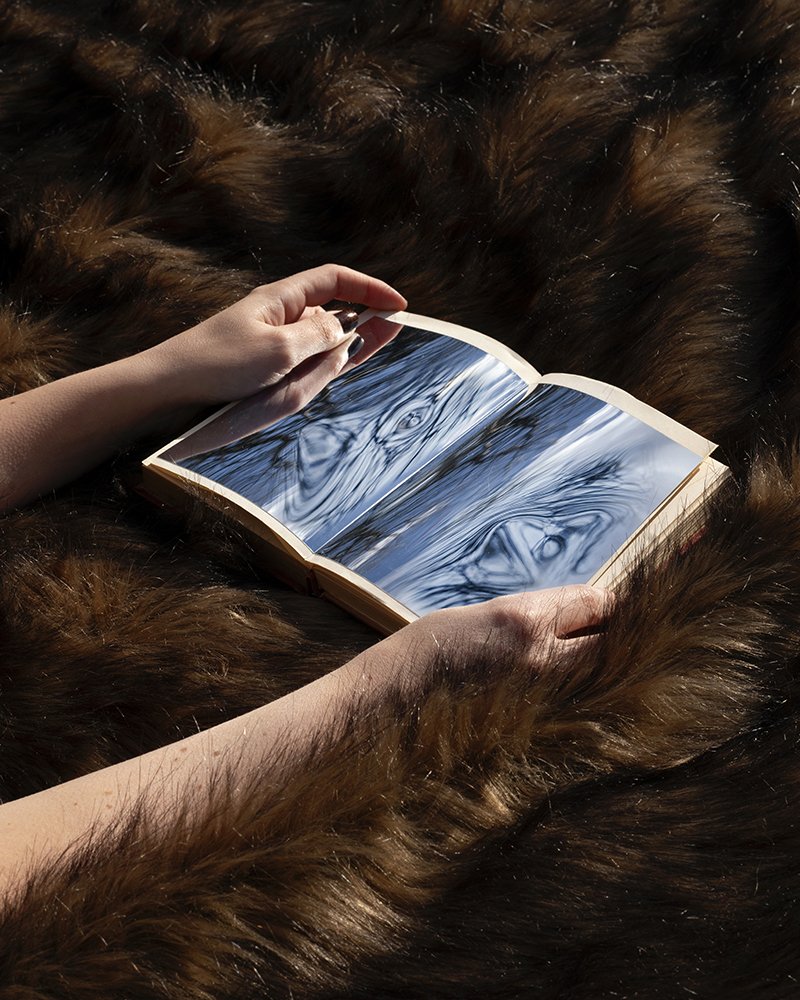

HA: They really are extensions of each other. Works from Kavana (generally made 2018-2020) are deep dives into Jewish iconography; the focus of these works prioritize Jewish symbolism to comment on ritual, memory, and narrative. They largely focus on the visible. They ask what certain Jewish symbols mean, how those objects transform inside a photograph. A Permanent Home in the Mouth of the Sun, however, finds similar inspiration from the immaterial motifs that perpetuate Jewish culture. They’re focused on the invisible. They ask how Jewish folklore stories are told; what themes do we pass down in our narratives?

When editing these intertwined projects together for exhibitions and such, I love to create overlap between photographs one can point to and say “right here is the Jewish object,” and images that feel more ethereal and draw from Jewish narrative. It creates an interesting dialogue, and considers what we designate a “Jewish” photograph.

JTD: As you mentioned, you made much of this new work over the past two years in isolation, due to the pandemic. How did this isolation, and the pandemic more broadly, affect your work?

HA: Before the pandemic, I was photographing strangers in their homes, traveling far distances, and working very quickly. During this time period I found myself often fixating on one particular Judaic object at a time, researching and photographing it, and then moving on to the next material. It was immensely productive. And so very fast. By myself (with my partner and dog) in this beach house, I had nothing but time as the early days of the pandemic unfolded around us. The abrupt change of pace instilled a new approach to image-making that, frankly, did not exist in my workflow beforehand—working slowly.

This new pace, in addition to reading Yiddish children’s folklore anthologies, got me thinking about the way Jewish stories are repeated across different environments and how self-portraits engage similar modes of motif repetition. These narratives started making their way into self-portraits that mirror the ways that Jewish stories are shared.

The images reject a static answer and repeat familiar symbols to stretch their hands across time, land, and set conclusions. I’m not sure I would have gotten to this line of thinking if not for the circumstance of isolation forging new chapters.

JTD: Rather than working in distinct projects, it seems that one series somewhat naturally leads to the next, and that all of your work is connected both visually and thematically. How do you conceptualize your working process, both in the day to day and over a period of many years?

HA: They overlap naturally. I have noticed that every few years, I step back to see another branch of the same tree has grown enough to call it a project. But they all share the same roots. I pull images that are taken years apart in and out of a grouping however feels right for that specific installation. I don’t particularly think indicators of linear continuation are necessary for this work, and I have come to love repeating myself, as so many Jewish stories repeat themselves.

JTD: Many of your photographs have strong, beautiful light, or a combination of intense highlights and dark shadows. How does your use of light visually connect to the content of your work conceptually?

HA: The way that sunlight carves the world it shapes is a central interest for me as a maker. It feels very sacred to me, and to this work. Where the light falls guides the narrative. Before I started letting Jewish thought shape my photographs, I had always considered my identities as both a photographer and a Jew as solidly separate. It was a strikingly clear moment to realize how very similar they are, with their rotation around light, their obsession with chasing the ineffable, their power to shape memories.

JTD: Do you view your work as having an educational or activist component?

HA: I would say so, although I think the images take a more subtle approach to sharing information. They all contain sites of Jewish culture; they share translations of stories, interpretations to rituals, offerings of memories. They are, undoubtedly, a resource and an archive, but they are not authoritative. I like to think the work presents a less concrete and more environmental sense of truth. Two Jews, three opinions.

JTD: What are you currently working on, and what’s on the horizon for you as an artist?

HA: I’m excited to have an upcoming solo exhibition of my work at Gallery 263 in Cambridge, MA that is on view June 9-July 9, 2022. The show features much of the work that we’ve been talking about here. Because it is showing work from my many environments over the last few years (including work from Kavana and A Permanent Home in the Mouth of the Sun), I’m honoring those landscapes with the title With Rifts and Collapses—a line from the Yehuda Amichai poem “The Jews,” which I’ll leave you with here:

The Jews are not a historical people

And not even an archeological people, the Jews Are a geological people with rifts

And collapses and strata and fiery lava.

Their history must be measured

On a different scale.

JTD: Wonderful, thanks so much Hannah!

All images © Hannah Altman