Q&A: Debi Cornwall

By Hamidah Glasgow | April 26, 2018

Debi Cornwall is a conceptual documentary artist who returned to visual expression in 2014 after a 12-year career as a wrongful conviction lawyer. Her values as an advocate and trained mediator, as well as her background representing innocent DNA exonerees, inform her visual work, which examines American power and identity in the post-9/11 era. Her series marry empathy and dark humor with structural critique.

While completing a Bachelor's degree in Modern Culture and Media at Brown University, Cornwall studied photography at RISD. After working for photographers Mary Ellen Mark and Sylvia Plachy, as an AP stringer, and as an investigator for the federal public defender's office, she attended Harvard Law School and practiced for more than a decade as a civil rights attorney.

Since 2016, she has been honored as a Baum Award for an Emerging American Photographer nominee, and as a recipient of Duke University's Archive of Documentary Arts Collection Award for Women Documentarians, the Lianzhou (China) Foto Festival Punctum Award, the inaugural Fotofest Charles Jing Fellowship, a Harpo Foundation Visual Artist Grant, and a 2017-19 Center for Emerging Visual Artists Fellowship.

HG: I have been following this project since I first saw the work at Photolucida many years ago. It has evolved so much since that time. What you are most interested in talking about at this point in the project?

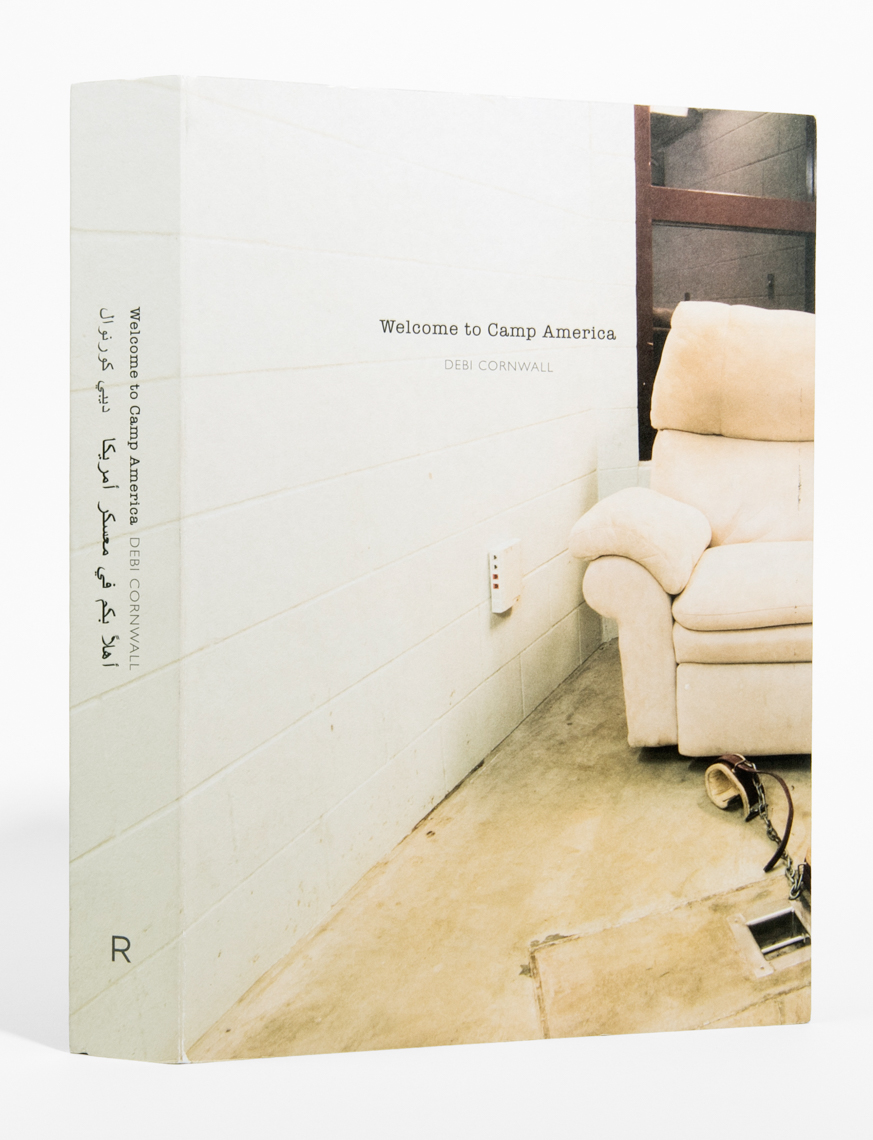

DC: Hm. This is a good question. Top of my head as I caffeinate here: I guess what is most of interest to me at this point is nontraditional ways of looking at and presenting work on "documentary" subjects, ways that invite or provoke the audience to do some of the work, if that makes any sense? i.e. I'm not using a traditional photoessay form or providing all of the information you might want. No one man's story. Instead I'm trying to provoke curiosity, to spark the viewer to want to go out and learn more. Also, addressing the "what is the point of this" or "what does this have to do with me" question. For me the subject matter is both about Guantánamo Bay and also more generally about the ways our society dismisses those we fear, those who are different than we are. There's intersectionality with so many other movements, though those impacted by the "War on Terror" are rarely part of the discussion of alliances (i.e. Women's march, BLM, etc.) Who is "us" and who is "them"? I'm trying to reframe around what we have in common... Ultimately it's all about American-ness. Is Guantánamo a state of exception? That's how I approached it originally. Or is it actually emblematic of our pre-existing systems, mindsets, and frameworks?

HG: I'd like to hear more about this idea of American-ness. When you say that there's intersectionality with so many other movements like #metoo and BLM, the issue is ultimately about who is considered Other. In the case of Guantanamo Bay, how does this Othering present itself and how does it relate to the groups you mentioned?

DC: I went to law school and practiced as a civil rights lawyer for over a decade representing innocent DNA exonerees in lawsuits seeking to identify, expose, and rectify systemic misconduct in law enforcement. That I chose to work within the system in order to improve it situates me as someone who believes in the value of America’s democratic institutions, our Constitution, and laws, when fairly applied. My work was, essentially, to use each case to try to improve the criminal justice system. When I stepped away from litigation and returned to visual expression in 2014 with Welcome to Camp America, I considered the “War on Terror” prisons at the U.S. Naval Station in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba to be a state of exception: Muslim men suspected of plotting against the United States held for years without access to lawyers, without charge or trial, indefinitely, subjected to torturous interrogations and living conditions, on an offshore site controlled by the United States but selected precisely to be outside the jurisdiction of U.S. courts. It struck me as un-American to jettison the critical safeguards of due process and fair trials simply because, as a nation, we were afraid. Sixteen years later, of the 780 men once held, 41 remain, including five who were cleared for transfer years ago, five facing military proceedings, and thirty-one “forever prisoners” deemed untriable, yet too dangerous to release.

HG: Your search for the men that have been released from GB is an exercise in shedding light on the parts of these kinds of stories that the general public don't hear. What has been your experience with the men and the process of finding them and their 'after' stories and lives?

DC: Over the course of my three trips to make photographs at “Gitmo;” my visits with fourteen men once held there, after they had been cleared and released to nine countries; and engaging with global audiences about these questions, my perspective has shifted. The denial of personhood for suspect Muslims at Guantánamo Bay now feels to me like the logical conclusion to policies and practices that play out every day here at home. None of the men held offshore at Guantánamo Bay is American, so they are most easily dismissed as “Other.” But their struggles are very much like the struggles facing my former clients, exonerees within the United States who try to rebuild their lives after years of wrongful imprisonment. And their suffering has a common origin. DNA exonerations illuminate misconduct that plays out across the board against marginalized groups, “innocent” and “guilty” alike. The same white fear that gave rise to “Gitmo” leads to mass incarceration and police shootings of people of color, as well as legal doctrines that give the benefit of the doubt to those enforcing the system instead of those on the receiving end of it. Likewise with selective policies and messaging that render suspect brown people seeking permission to enter the United States for asylum, work, or merely a better life. These phenomena are not unique to our present political moment, but, as you rightly note, have deep roots in American history.

Part of my strategy is to ask "what do we have in common?" What do we have in common with those who look different, or worship differently, those we fear or those we hate? In the context of Guantánamo Bay, that felt like a radical question to ask. In my experience there, though, I found that those on both sides of the wire had two things in common: nobody had chosen to live there, and nobody was sleeping through the night. With this new perspective, a different kind of conversation becomes possible, across a wider audience.

I carried this implicit question through in the way I photographed released men, from Albania to Qatar. The military prohibits photographs of faces at Guantánamo Bay. What better way to convey that the trauma persists long after the body is freed than to photograph released men as though they were still at Gitmo? But the “no faces” approach has another side-effect. As in a cinematic point-of-view shot, it invites the viewer to stand in the subject’s shoes, to imagine what life is like for him. What do we have in common with these men? Those I spent time with want the same things we all want in the end: a safe home, a family, and a way to support them.

Though each of the men I photographed was cleared and released, securing these basics is not so simple. For example, the Chinese Uighurs and Uzbeks who resettled in Albania were granted asylum, but no national identity cards. Without those papers, they may not legally register for a bank account, a driver’s license, or a mobile phone. One man who speaks multiple languages and now holds a graduate degree had to turn down an executive position because it required international travel. And he is not free to leave Albania. It’s confusing and incredibly frustrating for men who wish to move forward with their lives.

The textual thread of my book implicitly repeats the “what do we have in common” question as well, inviting the reader to identify with the narrating “I,” then disrupting assumptions with a twist at the end. Who is “us,” and who is “them,” after all?

HG: Do you have any examples of people that were touched enough by the work to reconsider their previously held position? I am looking for some hope. Is that asking too much in this case?

DC: There is hope. I see a shift happening with the images, and in relationships formed between those who have been on both sides of the wire. For example, Moazzam Begg, a released man and activist who wrote an essay for my book, has befriended one of his former guards and hosted him in his home. They have given talks together, and it's a powerful alliance.

At a panel discussion at my exhibition at Steven Kasher Gallery in Chelsea last fall, I included a releasee (via Skype), a former interrogator, and a civil rights attorney. It was a remarkable and meaty conversation. During the Q&A, someone in the audience addressed the released man and apologized "on behalf of the American people." The entire audience, standing room only on a lovely fall afternoon, applauded.

By inviting the viewer to stand in each man's shoes, by asking what we have in common, whether between prisoner and guard, citizen and suspect, American and "other," we can fundamentally reframe the debate, from fear and despair, to hope and constructive alliances.

HG: Thank you, Debi.

All images © Debi Cornwall