Q&A: Crystal Z. Campbell

By Rafael Soldi | March 8, 2018

Crystal Z Campbell is an interdisciplinary visual artist and writer of African-American, Filipino & Chinese descents. Campbell uses art as a tool and history as material to rupture collective memory, imagine social transformations, and question the politics of witnessing. Campbell exhibits internationally. Selected exhibitions include SculptureCenter (US), ICA-Philadelphia (US), Artissimma (IT), Studio Museum of Harlem (US), BRIC (US), Visual Studies Workshop (US), Futura Contemporary (CZ), Project Row Houses (US), Art Rotterdam (NL), and de Appel Arts Centre (NL). Selected honors include Skowhegan, Rijksakademie van beeldende Kunsten, Whitney Museum's ISP Van Lier Fellowship, Mondriaan Fonds, Smithsonian Research Fellowship, Yaddo, and MacDowell Colony, amongst others. A former social worker, Campbell holds an MFA from the University of California-San Diego. Campbell is a third-year recipient of the Tulsa Artist Fellowship.

Rafael Soldi: What was your path to art? How has your background and heritage informed your practice?

Crystal Z. Campbell: I grew up in Oklahoma and was raised by a Filipina and Chinese mother and an African-American father. I had a very small group of people who had similar backgrounds to mine, but it was never possible to blend in within any large group. Without knowing it at the time, I began to draw and use art strategies as a way to spend more time on subjects that seemed incoherent, on events that seemed incomplete, and people that seemed unacknowledged.

RS: You’ve described your work as the excavation of unsettled historical narratives. What draws you to these narratives?

CZC: A few years ago, I was listening to a podcast on death. There were a number of possibilities on how death could be defined, some of which related to the heart, breath, and brain, but mostly scientific and Western conceptions of death. And I remembered another anecdote on death—death occurs when people stop speaking your name. I thought this was more fitting, this social death, and how certain institutions are pre-conditioned around the social death of people of color. I'm drawn to stories that resonate with me in a personal way. When I feel that a story took a turn towards some sort of injustice, I feel there is an opening for my practice. I know I will need to make a work or write about it when the story stays at the forefront of my thoughts. I am constantly refining my work as an interdisciplinary artist and storyteller: how can art be used to rupture stories, transplant stories into a different space and time, play with alternative narrators, catapult the viewer into the role of witness, and suggest endings that fail the test of tidiness.

RS: Somewhere in Tulsa there is a mass burial ground filled with bodies that has gone un-investigated. Your piece Searcher recognizes those bodies and in a way calls a search for them into action. The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre was unknown to me; can you tell us about this event how this piece operates?

CZC: A question I like to bring with me when I move through this world is: What happened on the ground that I stand on? I grew up in Oklahoma, and always wanted to leave. I stayed here until the age of twenty-five, excepting a year I took off to study abroad in Spain. Two years ago, I returned to Tulsa after a ten-year hiatus when I was awarded the Tulsa Artist Fellowship. Something that drew me to this return, including the bonus of my mother's home-cooked adobo and my father's calm, was my interest in looking at the history of the Tulsa Race Massacre. This history was largely suppressed, and not taught in the curriculum, paving the way for historical amnesia.

When I landed in Tulsa, I had this fantasy that I would be reminded of the history of Greenwood and that something that embodied that history would be tangible and evident to me when I took walks around my neighborhood. I was surprised to find on the former site, I could order a hot dog and watch a baseball game without any mention of the Tulsa Race Massacre. I began digging in the archives to find more evidence. Some reports from the massacre estimate three-hundred deaths, while others say there could be thousands if only the paperwork were accurate, though a formal search for a mass grave was never conducted by the state. I imagined Searcher as a public call in search of the people whose lives or trajectories were interrupted by this massacre. Death counts are unreliable––trauma is encoded in our DNA and carries on for many generations.

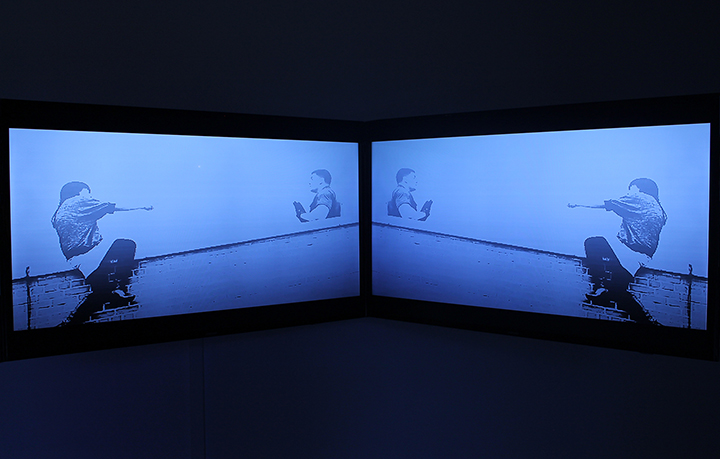

© Crystal Z. Campbell, Searcher

Searcher illuminated the massacre grounds after dusk for a few hours each night and is a symbolic search for those who were never accounted for after the riot, missing persons who fled or whose death were covered in mass burials or other means. Additionally, I wanted to think about Juneteenth and the messenger who didn't make it to deliver the news of freedom with the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. While searchlights are now co-opted for advertising, historically searchlights were used in periods of war to signal allies or enemies. For the last two years, I have installed Searcher on the grounds of the massacre next the highway that bisected the rebuilt Greenwood community. Along with urban renewal and prolonged neglect by local government, there is a long history of disenfranchising, displacing, and intimidating the North Tulsa community. Searcher is a public meditation on this history and how historical approaches translate into the present.

RS: Your practice questions the politics of witnessing. Historically, and today, some voices have more power than others in the accounting of events—whether it is the witnessing of a crime or the witnessing of history over centuries. Our social and political systems muffle the voices of those whose witnessing is ‘problematic,’ holding hostage the answer to, who can see? To you, who can see?

CZC: Witnessing is a political act. Witnessing can function with and independently of silence. Someone shared with me recently an anecdote about a friend whose family held photographs and negatives of the Tulsa Race Massacre, attributed to an elder relative who was a photographer. Later in the conversation, it was revealed that these photographs were burned. Why was this evidence burned? Now it is only a rumor. And I have witnessed a rumor and the possibility that something in the rumor, if true, could have complicated the collective narrative around what we think we know. The story of the Tulsa Race Massacre is like many other justifications for lynching, that a white woman was assaulted by a black man in an elevator. Perhaps if the story were reversed, would it have resulted in threats on her life in the same context? Emmett Till's death highlights how false narrators, such as Carolyn Bryant, have the power to use social codes of witnessing to uphold institutional and systemic codes of violence. Art can be incredibly useful in situations to mediate conversations and begin a dialogue where there are traces of historical distrust.

RS: Continuing this conversation about erasure, when did you first hear about Henrietta Lacks’ story and how has it shown up in your work? Why is Lacks’ story so important?

CZC: I learned of Henrietta Lacks reading an article while I was a fellow in the Whitney Independent Study Program and living in New York City. I was priced out of the city, and took an opportunity to move to Amsterdam for a two-year fellowship at the Rijksakademie. Her story was heavy on my mind during this transition. When I moved, I began thinking about Amsterdam's history and connection to the history of diamonds through colonial acquisitions and diamond cutting and polishing by Jewish families in Amsterdam who were interned and killed during World War II.

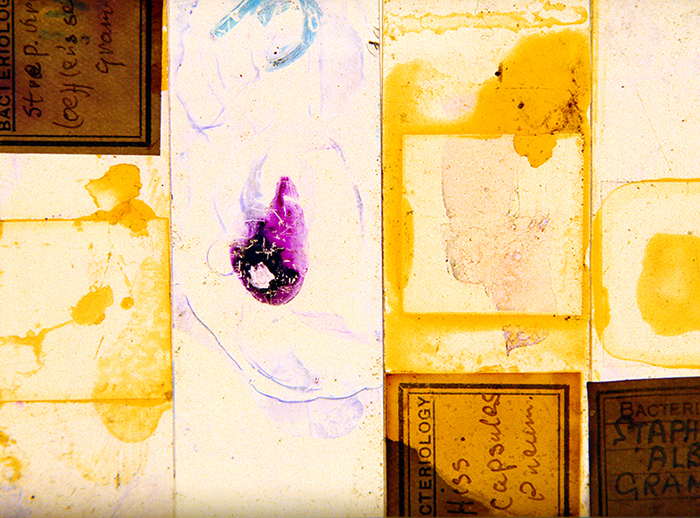

Henrietta Lacks' cells, an African-American woman whose cells were taken without her consent, is credited with having biological material that led to cures for polio and tuberculosis alongside many scientific developments. Her identity was erased for many years, and she long went unrecognized despite millions of people benefiting from the research and billions made in biotech industries with her biological imprint. I've made numerous works on Henrietta Lacks and there are a few that I am still in search of the right collaborator to complete. I was fortunate to work with a molecular geneticist in Amsterdam. Together, we grew Henrietta Lacks' cells on diamonds as a symbolic resting place for her immortal cell line and a question about the value of forever. Whose stories and bodies are valued and considered worthy of foreverness, of testimony, of an archive?

RS: For Go-Rilla Means War you hand-scanned 20,000 frames of a fragile and neglected civil rights-era roll of motion film that you found. What came out of this process and how did this slow acquaintance with the material change your relationship with the subject? How is it presented now as a final piece?

CZC: Seven years ago, I had a serendipitous encounter. Walking with a friend of mine through Bed-Stuy, we stumbled into the defunct and now demolished Slave Theater. As we were leaving, my foot struck a hard surface, which turned out to be a 35mm movie reel. I spent four months scanning 20,000 frames from the film. The film was diagnosed with vinegar syndrome. Not only did it smell rancid, parts of the film would simply tear apart and flake off as I handled it. It had no titles, credits, or a soundtrack. I decided to collaborate with the filmmaker and work on the soundtrack and voice over to bring it to completion. The film itself is a witness, each frame having been exposed to people, places, and a set of conditions that can never be replicated. The film is a forensic witness as well––the film material held dust, scratches, hair, fingerprints, and other traces, and I've added fingerprints and sweat of my own.

Go-Rilla Means War has shown in film installations at BRIC and Visual Studies Workshop and an installation with two slide projectors at SculptureCenter. I'm working with Visual Studies Workshop Press to release a limited edition artist book for Go-Rilla Means War later this month and I would like for it to continue shape-shifting, like an art version of that childhood game of telephone where each bit of language shifts from person to person with people sharing the story they want to hear.

RS: Tell us about your upcoming project in Nashville.

CZC: I am at work on my first public commission that will open in Nashville in June 2018. Curator Nicole Caruth invited myself and other artists across the US to find deeper connections between foodways, community well-being, and gentrification. In our conversations, we've talked about the visible markers of gentrification and how Nashville is now marketed as a "foodie" city, a branding that lures both tourists and new residents. At the same time, there's a complex dynamic of being a "foodie" city and what communities in the city have access to healthy foods and what communities reside in food deserts and are prone to displacement. I'll keep the details under wraps for now, but my project will take place in the Nashville Farmer's Market and forge a link between Nashville's Civil Rights history and a relic of gentrification.

RS: What are you obsessed with right now?

All things green. Ginger. Mustard. Nervous laughter.