Q&A: Bethany Collins

By Rafael Soldi | December 8, 2022

Bethany Collins is a multidisciplinary artist whose conceptually driven work is fueled by a critical exploration of how race and language interact. Collins received her BA in Studio Art and Photojournalism from the University of Alabama in 2007, and her MFA from Georgia State University in 2012. She was the 2013-2014 Artist-in-Residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem, and 2019 Public Humanities Practitioner-in-Residence at Davidson College in Davidson, NC. Collins was awarded the Hudgens Prize in 2015 and Efroymson Contemporary Arts Fellowship in 2018. Upcoming and recent solo museum exhibitions include presentations at the University Galleries of Illinois State University, Frist Museum (Nashville, TN), Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts (Montgomery, AL), CAM St. Louis, The University of Kentucky Art Museum (Lexington, KY), and the Art Institute of Chicago. Collins currently lives and works in Chicago and is an Assistant Instructional Professor in the department of visual arts at the University of Chicago.

"(Unrelated)"

Chalk and charcoal on chalkboard, 48" x 70", 2012

Rafael Soldi: Hi Bethany, thank you so much for taking the time to chat with us. I would like to start by addressing language, which is at the core of your work, both as subject and as material. We’ll get a more nuanced sense of your use of text and language as we talk more, but where did your interest in language begin? Specifically, historical language and text archives as opposed to contemporary texts (with some exceptions)?

Bethany Collins: So glad to be in conversation, Rafael. The White Noise series in grad school was my first attempt at using language. The threads of that series—other peoples' language, repetition, erasure and residue—still reach throughout every work I've made since then. I was listening to a conversation moderated by Elizabeth Alexander recently, where she compares poems to monuments. The scale of each is quite different, but she says both outlive their makers and are forces into the future, a way to revere this moment into the unknown next. In my practice, working with historical texts—outdated dictionaries, court documents, national anthems and newspaper archives—is a way to understand the present through the past and then ask us all "again? will we do this again?" into the future.

RS: I’m interested in the ways your material and formal processes are critical to your conceptual frameworks. Whether it is the disintegration of paper as a metaphor for our fragile institutions, or the deliberate destruction of words and materials, or the chaos of voices in your sound works. Can you talk about how you balance these tactile and material choices with the research and conceptual aspects of your work?

BC: Form is equal to concept. In the Contronym series, it matters that the contronyms—words that evolved over time to contain their own opposing meanings—are excerpted from an American Heritage Dictionary from the 1980s and printed on American Masters Bright White paper. It matters that A Pattern or Practice is embossed onto Somerset Radiant White paper, so each page constantly reflects light, making the emboss and the report itself literally hard, painful to read. The idea of these works wouldn't exist without these materials and laborious processes.

RS: Since we’re discussing process, I’d also like to talk about labor. Most of your work is labor-intensive and often repetitive, you could even say they are private performances. I can’t help but think of your labor as an integral part of the work—erasing, engraving, slicing, writing. You’ve mentioned too that this labor is about control and I imagine it is also about reclaiming and carving out a space for yourself in history. Can you expand on this?

BC: Labor has long been integral to my practice, but who labors is changing. What I'd like is to transfer the necessity of labor—often to the point of pain—onto the viewer. I no longer need to host in that way. So, instead of obsessing and writing a problematic text until my hand hurts in the White Noise series, instead, 100 lyrical versions with the same melody can be sung, endured and transformed by others. In the sound installation of America: A Hymnal, that debuted at the Peabody Essex Museum in 2020 before traveling to Seattle when you visited, that transformation requires six singers performing all 100 versions of My Country 'Tis of Thee separately, which then become combined solos in one space. It usually takes about 4 hours to sing all 100 versions. Endurance is required of the singers and listeners.

Find, 1982 (From the Contronym series)

American Masters paper and Black Magic erasers, dimensions variable, 2017

A Pattern or Practice

Blind emobssed Somerset paper, 8 3/8” x 10 ¾” each, 2015

RS: Yes, and this makes me think about repetition and accumulation as well, which both enhances and diminishes meaning in your work.

BC: Repetition allows you to divorce the word from its original meaning. Say a word enough times and you forget its meaning altogether, not to mention its common pronunciation. But repetition might also allow for transformation, the potential for new meaning to be attached. Again in the White Noise series, re-writing a problematic question or statement over and over and over on the chalkboard meant that I could obsess on the question, unpack it fully, expel it from my practice, and then transform the original problem into something more beautiful. That transformation only happens in the hundredth writing, not the first or eleventh.

RS: Your recent solo survey exhibition at the University Galleries of Illinois State University is titled A Pattern or Practice. Can you tell me more about that title and the artwork by the same name?

BC: A Pattern or Practice is a ninety-one piece wall installation of blind embossed portions of the U.S. Department of Justice investigative report on the Ferguson Police Department. In 91 pages, excluding the conclusion, the report meticulously details a systemic pattern or practice of unconstitutional policing of Ferguson's African American residents, which subsequently shapes the city's judicial practices. When the report was released, there was a law professor is St. Louis, Justin Hansford, who said reading the report was like being told that water is wet. Admitting an obvious truth can still be a remarkable act.

RS: You have produced a number of artist books exploring American hymnals and their many versions, and most recently an installation that includes wallpaper and recordings of performances of these songs. I was lucky to experience it at the Seattle Art Museum recently. Many of the hymnal versions are set to the exact same music but their lyrics or purpose are in opposition to one another, which you said “reveals something about who we are.” What was your thought when you discovered this, and how do you think this paradoxical opposition mirrors our world?

BC: After the 2016 presidential election, one of the first works I made was America: A Hymnal, an artist book made up of 100 versions of My Country 'Tis of Thee written from the 18th-20th centuries. This used to be a much more common early American practice, to keep a familiar melody and re-write the lyrics in support of various social or political causes—including revolution, suffrage, Native sovereignty, temperance, the Confederacy, and abolition. Each rewriting articulates a version, an often contradictory version, of what it means to be American, forever bound together in opposition within the hymnal. The hymnal, audio installations and performances that followed were a way for me to grapple in that moment with a familiar yet somehow unexpected national betrayal.

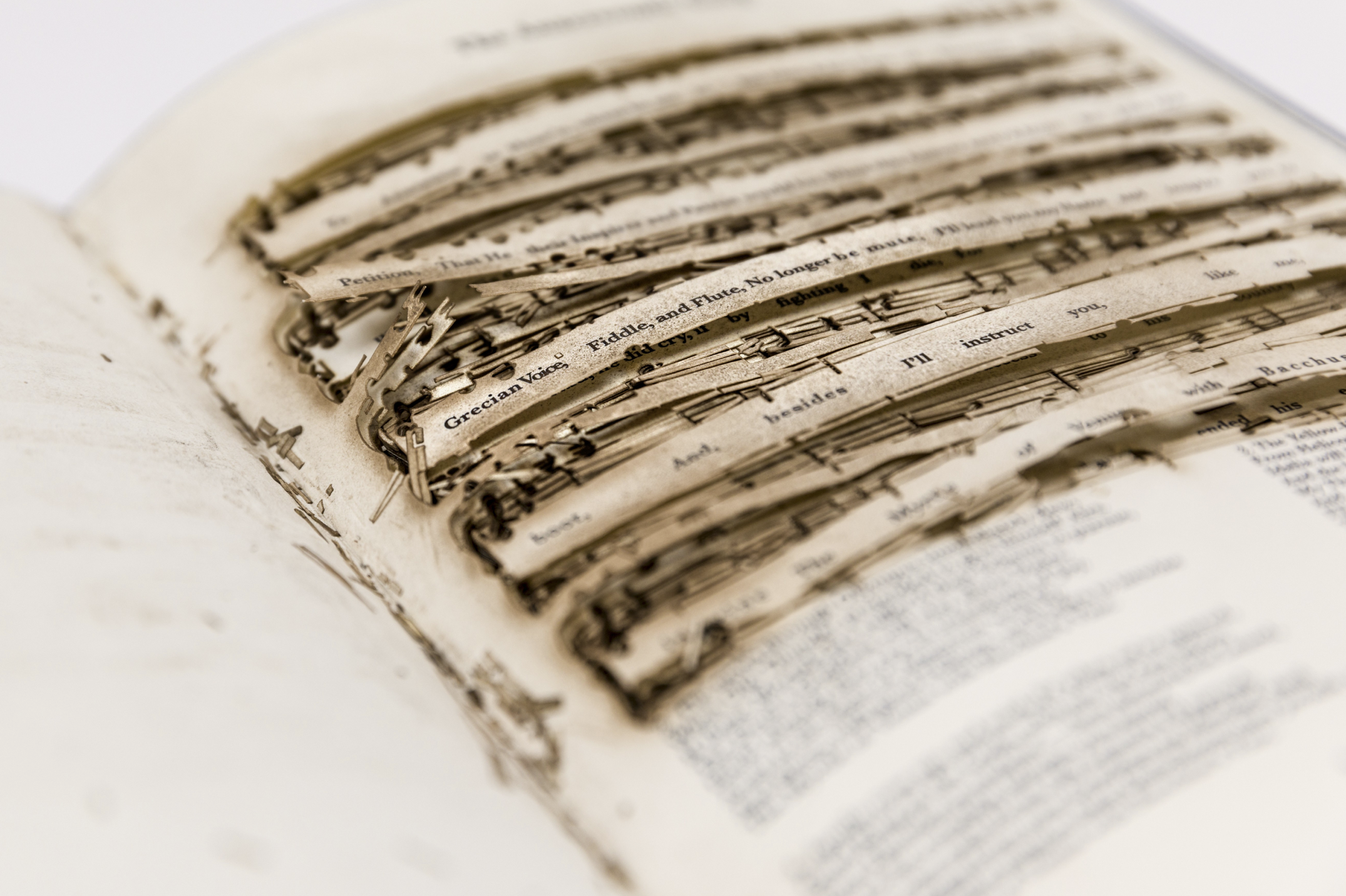

America: A Hymnal (interior)

Artist book with 100 laser cut leaves, 6" x 9" x 1", 2017

The Star Spangled Banner: A Hymnal

Artist book with 100 laser-cut leaves, 9" x 6" x 1", 2020

RS: Thank you, Bethany. I have many more questions but I’ll stop here for now. Any upcoming projects we should keep an eye out for?

BC: Next year, 2023 will be a year of performances, beginning with a polyphonic performance of America: A Hymnal at the 15th Street Friends Meeting House in New York City as part of Visual Record at the Print Center New York. Followed by a suite of three new performances at Bryn Mawr College.

RS: Terrific, we look forward to seeing these performances.