Q&A: Annabel Daou (Part II)

By Rafael Soldi | July 19, 2022

Annabel Daou’s work takes place at the intersection of writing, speech and non-verbal modes of communication. Her paper-based constructions, audio/video works and performances explore the expressive possibilities of ordinary language, and reveal intimacies between individual and collective experience. Frequently, her works evoke moments of rupture, chaos, instability and misunderstanding but always with the tenuous possibility of repair. Daou was born and raised in Beirut and lives in New York.

Daou’s work has been shown at The National Museum of Beirut; The Park Avenue Armory, New York; KW, Berlin; The Drawing Room, London; and The Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin. Public collections include Baltimore Museum of Art; The Menil Collection, Houston; The Brooklyn Museum of Art; The Vehbi Koç Foundation, Istanbul; the Ulrich Museum of Art, Wichita; and The Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven. Daou was recently a Pollock-Krasner resident at ISCP in 2019-20.

Gods and Grifters, Conduit Gallery, April 9 - May 14, 2022

Rafael Soldi: Hi Annabel, we last spoke in November 2016. I very much enjoyed our conversation then and I'm looking forward to discussing how your practice has evolved. Back then you described yourself as a language artist, and even though you deploy text as a formal element in your work, you said that "the expanse of language and its capacity to be limitless [represented a] space of freedom." How has your relationship to language evolved in the last five years?

Annabel Daou: It’s a pleasure to continue this conversation with you. Over the past five years the work has become more focused on performative and participatory projects, as well as sound and video. Language is still the primary subject, but I’ve stopped writing out words for the most part. Even in my paper based pieces, I’ve begun to find other ways to form words, building them up from torn fragments like a mosaic or cutting them out of or into microfiber paper. I think this has changed my relationship to language, or perhaps it’s the change in my relationship to language that has brought on this shift.

I think when I was doing more “writing,” it was a matter of creating terrains or spaces of meaning that were still much more tied to the way one encounters language in a book. Silence has become more important to me recently. I have the feeling that so much has been said and is being said, that I have only a few words, that there is only space for the most pared down, perhaps threadbare or skeletal remains of language, that only the smallest thing can have meaning or that we can only relate honestly to each other at the most basic and exposed level, at the level of our bones.

RS: How do you see your performance works in relationship to your material works, such as your paper-based constructions at your recent exhibition Gods and Grifters? Are they symbiotic?

AD: As performance and participatory projects have become more central to what I do, I’ve begun to conceive of the process of cutting out or suspending words/language as a performative element. At some level I think there was always that element to the process of making my work, even the paper and tape based earlier work that I discussed in our last interview. There, I was working with the idea of transcription, repetition and at times transliteration, as a means of rupture and repair. I see language now more as sound, as passing words, like a line of a song you catch through an open car window, like words fluttering, where the process of capture and suspension is a physical act.

With Gods and Grifters, I was also thinking about mesopotamian stone tablets where language is cut into the curved stone and the result appears to us from this point in history as a pattern, but deciphered they are lists, recipes, names, residues of everyday life. I have always been interested in what remains of our actions, of how we live or how others lived at different times in history, of what remains of our exchanges with each other. I’ve always attempted to make the work feel like a residue of that more than an object in its own right.

In the show there’s a work called thieves and lovers and it is a kind of list of things we, as a society have been:

We were thieves and lovers,

angels and architects

gods and grifters

We were fools and kings

We were builders and sailors,

traders and witches,

saviors and healers

warlords and liars

We were judges and carpenters,

We were saints and scavengers…

Another large work, another country appears from a distance as a pattern, an unfolding space, a net, a flag, or open pages where all that’s left are tangled lines, but in fact it’s mostly language, the repetition of phrases beginning with the word, “another.”

Another barricade

Another arena

Another surrender

Another defeat

Another epiphany

Another paradox

Another wasteland

Another danger

Another lack

Another substance

Another struggle

Another demand

Another regret

RS: Your ongoing project, Fortune, inquires into trust, intimacy, and power. It is structured around two questions: “where are you coming from?” and “where are you going to?” Tell me more about how this came about, why these questions? You've presented it in multiple venues, does this affect the outcome of the work?

AD: Fortune began in 2013 in conjunction with the exhibition of from where to where, a paper and sound piece first shown in the 2010 Cairo Biennial, which was shut down after the first week as protests began in Tahrir Square. The piece had been made in response to my earlier years in New York when I moved here from the war in Lebanon and people would ask me immediately where I was from. from where to where shifted that question about identity to a more immediate and even psychological question. I stopped people in the streets of New York and Beirut and asked them “where are you coming from?” and “where are you going to?”

FORTUNE, performance in residence at signs and symbols, 2019

Maybe it was this interest in what takes place at the level of the street that led me to become interested in fortune tellers, and the gendered and othered position that they inhabit. Fortune telling is ubiquitous in urban life even though it is illegal in many places including New York City where it’s a class B misdemeanor. In the depths of Dante’s Inferno the fortune tellers walk with their heads on backwards, punished for presuming to see the future. In New York you can advertise yourself as a psychic but not as a fortune teller. I was thinking about the fortune teller as a “stand in” for the artist. Someone who looks at the present in order to see the past and to project the future. Someone who holds some power, but who is also a hustler, a seducer, calling you over to put your hands out, to pay them. But there’s also something that the client wants, something that only the fortune teller or artist can give them.

I’ve done Fortune now in multiple places across the world, in institutions, galleries, parks, and in the street. In 2017 I rented a window space in lower Manhattan for several months and wrote “FORTUNE” in the window. I did not frame it as an art project and most of the people who came in were passersby. I sign the fortunes AD and date them. I like the fact that hundreds of people have a work of mine that is made solely for them. The experience of sitting across from a stranger whose hands are outstretched for 5 to 10 minutes wordlessly is both intense and meaningful. I don’t generally look up at people’s faces. The process is entirely silent, and I write a line of text for a line in their hand.

In 2018 Temporary Art Platform, a public art platform in Lebanon, commissioned artists to do projects that would appear in the daily newspapers. My work was an ad in the Daily Star asking people to send me an image of their hands. I wrote their fortunes and they were printed in the paper anonymously. People had to recognize their own hands to be able to read their fortune.

Other than in the newspaper version and in one upcoming book project, the process is the same, and it’s the idea of the oscillation of meaning and position and perception both for the participant and for myself that intrigues me. I do feel that Fortune reflects what I’m after in much of my work. It allows me to question social structures and contexts while also entering into a meaningful exchange with another person. And there is a residue to the process but also a kind of silence around it, which I feel allows for new understandings and misunderstandings and lines of connection between me as the artist and the public.

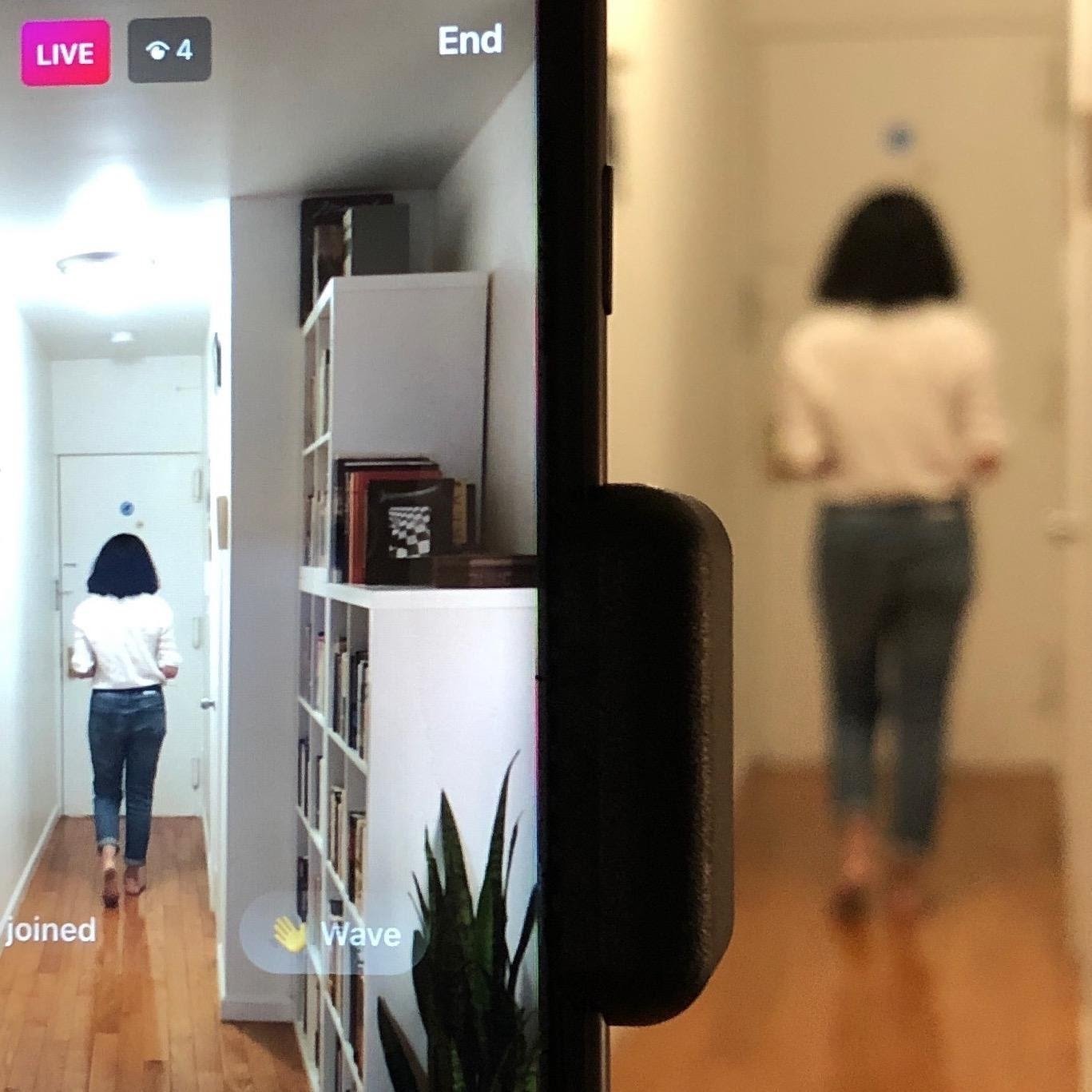

I will worry for you (from dusk till dawn), 2020, durational performance

RS: Early in the pandemic I participated in your durational performance I will worry for you (from dusk till dawn) at The Lobby. It was such a poignant moment, and everything felt so heavy. Releasing a single worry for you to carry on my behalf felt so powerful and I still think about it. Was this work in production before the pandemic began, or was it a response to it? Also, briefly, what's The Lobby?

AD: For a few years I had been running a project called the lobby with a friend of mine. I lived in an old building in Brooklyn that had a strange and beautiful lobby and so every few months we would invite artists to do a project there for a few hours and then come up to my apartment for drinks and food. The only rule was that they treated the space as a lobby not a gallery, a place one encounters on the way home or on the way to the street, a place where people come and go, meet or don’t meet, where things are left and passed by.

The community we were building was really great and mutually supportive and I had been thinking about how we are connected to each other in this context. I decided I would do a project myself, a live participatory performance where each participant would take on another person’s burden and then pass one of their own troubles onto the following person in a relay.

I was just beginning to organize the project in the first days of March 2020. Then suddenly the whole world went into lockdown, and it became impossible to imagine multiple people pacing the lobby. But at the same time the relevance of connecting to and caring for each other took on a new meaning.

I decided that I would take the worries on myself and that I would open the project to anyone who wanted to participate and send me a worry. I chose the period from dusk till dawn because that is often when our burdens feel the heaviest and we feel most alone. I sent emails to friends and acquaintances and publicized the performance through Galerie Tanja Wagner in Berlin and signs and symbols in New York. The result was that many of the participants were strangers to me and were living in countries across the world. Eventually it also became clear that it was not possible to do the performance in the lobby as it is a public space, so I decided to pace my own hallway.

On the evening of the performance I read each person’s worry silently (the entire performance was silent) until I felt that I was focused on it, and then I paced the hallway of my apartment with that worry on my mind over the period of time they had each selected. I had created 12 sets of worry beads, one for each hour and I moved through the sets as I moved through the worries. The performance was continuous with no more than a minute or two break every once in a while over the 12 hours. It was live-streamed on Instagram so people could watch me walk for them.

The string of beads in some way represents our connections to each other. As they moved in my hands, lightly tapping each other, they allowed for a sense of touch and connection, and provided an opportunity to reflect on how vital and how fragile those things are in our lives.

Set of 12 handmade strands of worry beads, 2020

Resin, ink and string

I did the performance once in March and then again in April of 2020. I did it one last time in Feb 2021 live streamed by Performative Screenings in Vienna. They were in another lockdown but they had windows into the space where they projected my entire walk so people could watch from outside the windows.

I’ve been interested in certain roles that have historically been the work of women. Fortune telling was one, but also wailing/crying women from history. The worry project had something of this concept in it. The idea that one could perform the sorrow or the concern of people they don’t know, and that that in some way could relieve the person or create a sense of solidarity. In some way the project has its origins in my memories of the long hallway in my childhood apartment in Beirut. Growing up during the Lebanese Civil War, I would watch the men pace back and forth often carrying worry beads in their hands.

RS: I've been thinking about how the pandemic may have impacted the frameworks and questions you're investing in your practice. Can you expand on this? Does What do you forgive yourself for? address some of this?

AD: I do wonder if it is the state of the world at the moment and the effect of the vulnerabilities and senses of isolation that have been made more apparent by the pandemic, but I feel that there is also a progression in my attempt to shed some of the concepts of physical materiality and objecthood from my work that has brought me to this place. Definitely I feel that there is a social and political engagement that is required of us, an understanding of our connections to each other in big and small ways.

What do you forgive yourself for? is a new work produced for the exhibition Auf Der Suche (in search of…) at DG Kunstraum in Munich (through July 22, 2022). Participants were invited to respond to the question, “what do you forgive yourself for?” and I recorded those responses in the first person. The participants remain entirely anonymous. The work deals with our expectations from both society and ourselves with regard to our behavior, our memories and our acceptance of ourselves and our pasts. In entrusting me to voice their self-forgiveness there is an exchange that subverts the notion of confession even as it affirms our need to be heard by others. This project is a shared act of vulnerability made possible by the fragile shelter of the many.

RS: In your recent participatory performance What can I do? What should I do? What will I do? you once again use questions to probe the public. What should we expect from this ongoing work?

AD: The work began as a performance at the Ulrich Museum of Art in Wichita, Kansas in conjunction with the installation of my sound piece, DECLARATION in a chapel on the campus of Wichita State University.

Declaration was made in 2019 and shown in New York at signs and symbols in January of 2020. The work borrows language from a large scroll-like piece titled WHEN IN THE COURSE OF HUMAN EVENTS, which was also part of the show. The work’s title and opening line is taken from the American Declaration of Independence of 1776. Reappropriated, the words become a universal template for articulating the pivotal moment when one is moved to act. Everyday expressions are interspersed with lines borrowed, stolen or gifted by artists, poets, writers and activists. The subsequent phrases shift between the personal and the political. DECLARATION merges my voice with sounds from city streets near and far. The work was made during a time of global protests (Lebanon, Chile, Hong Kong, etc.), when there was some sense that people were in the streets and that there was no turning back. But of course three months later the streets of the world were empty and our global sense of confusion was also imbued with questions concerning our responsibility to ourselves and to others. For the performance, I invited people to respond to the three questions: What can I do? What should I do? What will I do? I read their responses in front of the chapel with speakers playing it to passersby. The responses vary so greatly, but they reflect a sense of where we are right now and I’ve decided that I will continue to collect responses and eventually structure another performance, perhaps a reading by many participants and possibly an open mic for people to spontaneously share their responses.

WHEN IN THE COURSE OF HUMAN EVENTS, 2019-20 (detail)

Ink and correction fluid on microfiber paper

235”x 39”

RS: In our last conversation you mentioned a book you're writing, titled autobiography of a. What's the status of this endeavor, and is the first line still: “I’m walking backwards, for 120 days I would begin writing the story of my life…”?

AD: I finished the book in 2017, ten years after I began it. There’s a video that contains some of the language from the book, and I also produced a limited edition of 100 books that I included in a show, life itself at Conduit Gallery in Dallas in 2018. I was in discussion with a small press out of LA about publishing the book, but that was put on pause over the pandemic.

Very recently I have begun thinking of including some of the text in a new video and perhaps looking into publication again. It’s funny because the book or maybe the idea of it has been a kind of anchor for me over the years, a place where the “story” takes place, and in some sense a way of freeing me from telling a particular story in my other work.

The first line is still “I’m walking backwards, for 120 days I would begin writing the story of my life…”

The book ends this way:

She has gotten up from her chair and is walking over to the wall with a pen in her hand. She is scribbling something next to the piece that’s hanging there. She is leaving the room. I am still here and will stay a little while longer and maybe, before I go, I will read what she has written.

RS: Thank you so much Annabel, your work has helped me understand the world in more nuanced ways, and I'm grateful for your insights during this conversation.

AD: Thank you so much, Rafael. I appreciate your sensitive questions and this opportunity to revisit our first connection.