Book Review: “Mischling 1” by Sara Davidmann

By Kelly Lee Webeck | August 25, 2022

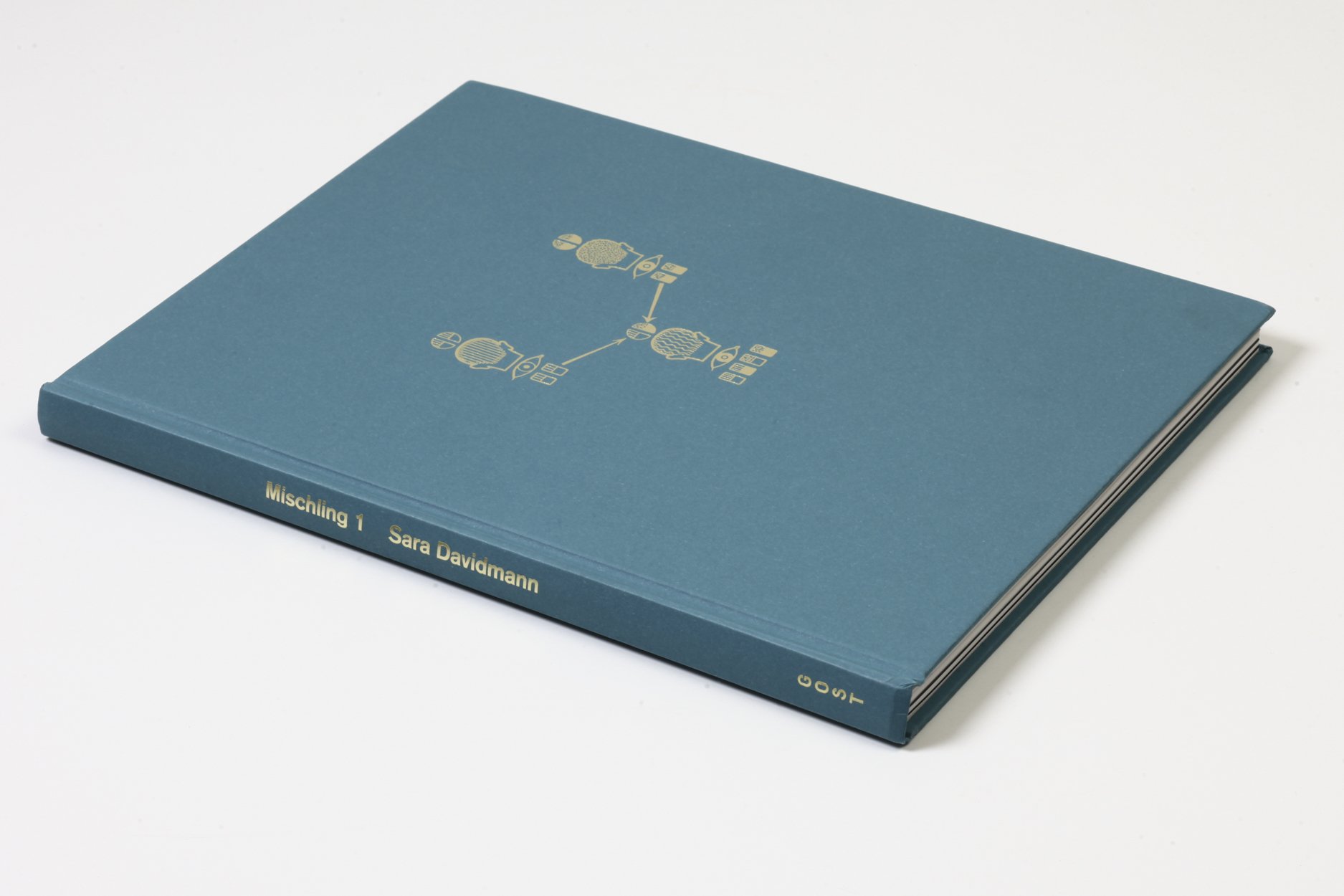

Published by GOST Books in 2021

9" x 12" / 116 pages / 105 images, 10 images printed in metallic silver on uncoated black paper, 5 images printed in metallic copper on black uncoated paper / Case Bound / Text by Sara Davidmann and Philippe Sands

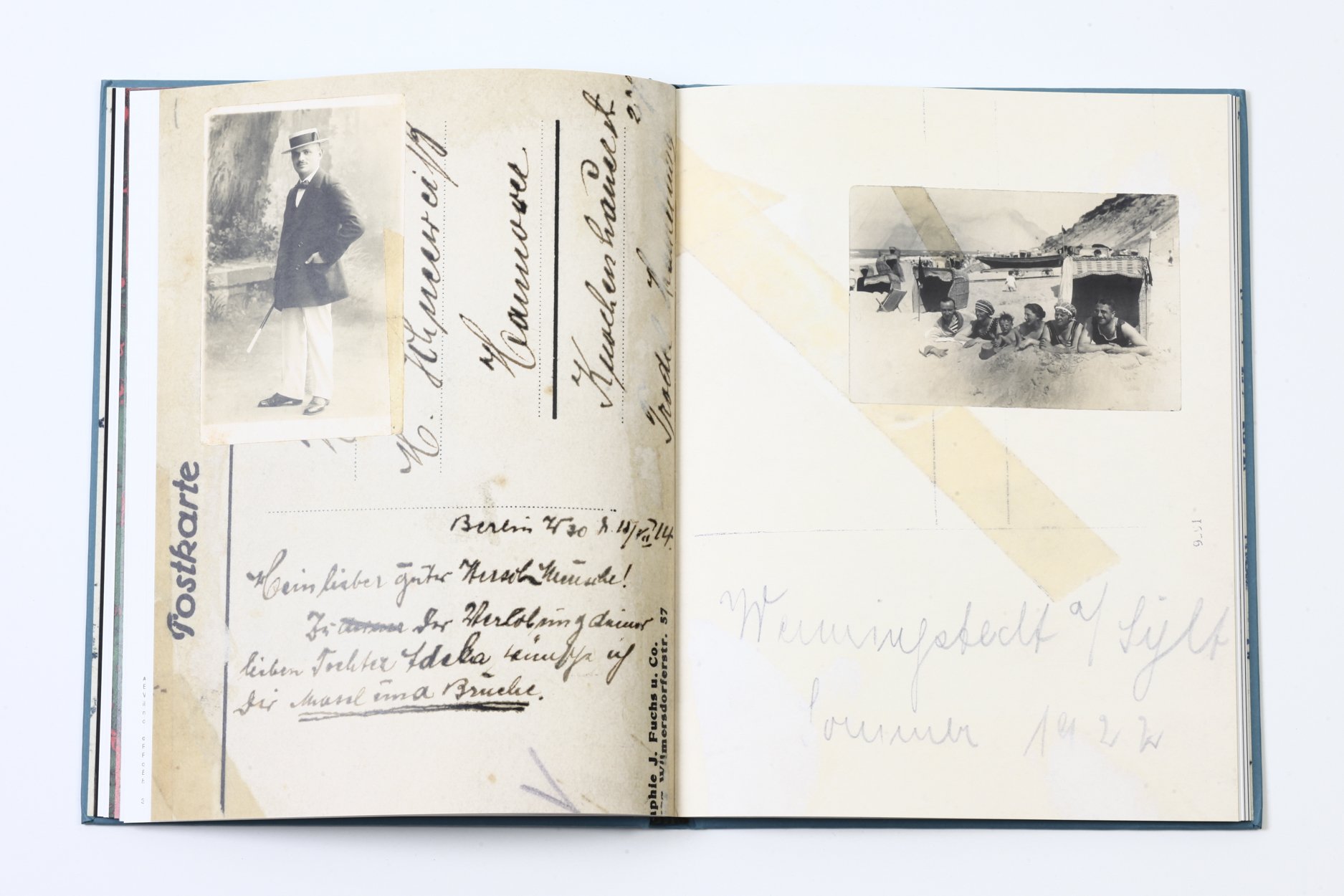

Sara Davidmann is the child of a Holocaust Surivor. This was not something that ever defined who she was as an artist or as a person until many years following the death of her father. After the discovery of a family photo album, she wanted to learn more and started to search in historical archives. Parallel to this research, Davidmann began experimenting with images from the family album within her studio. This led to a body of work titled My name is Sara, which Mischling 1 is a part of.

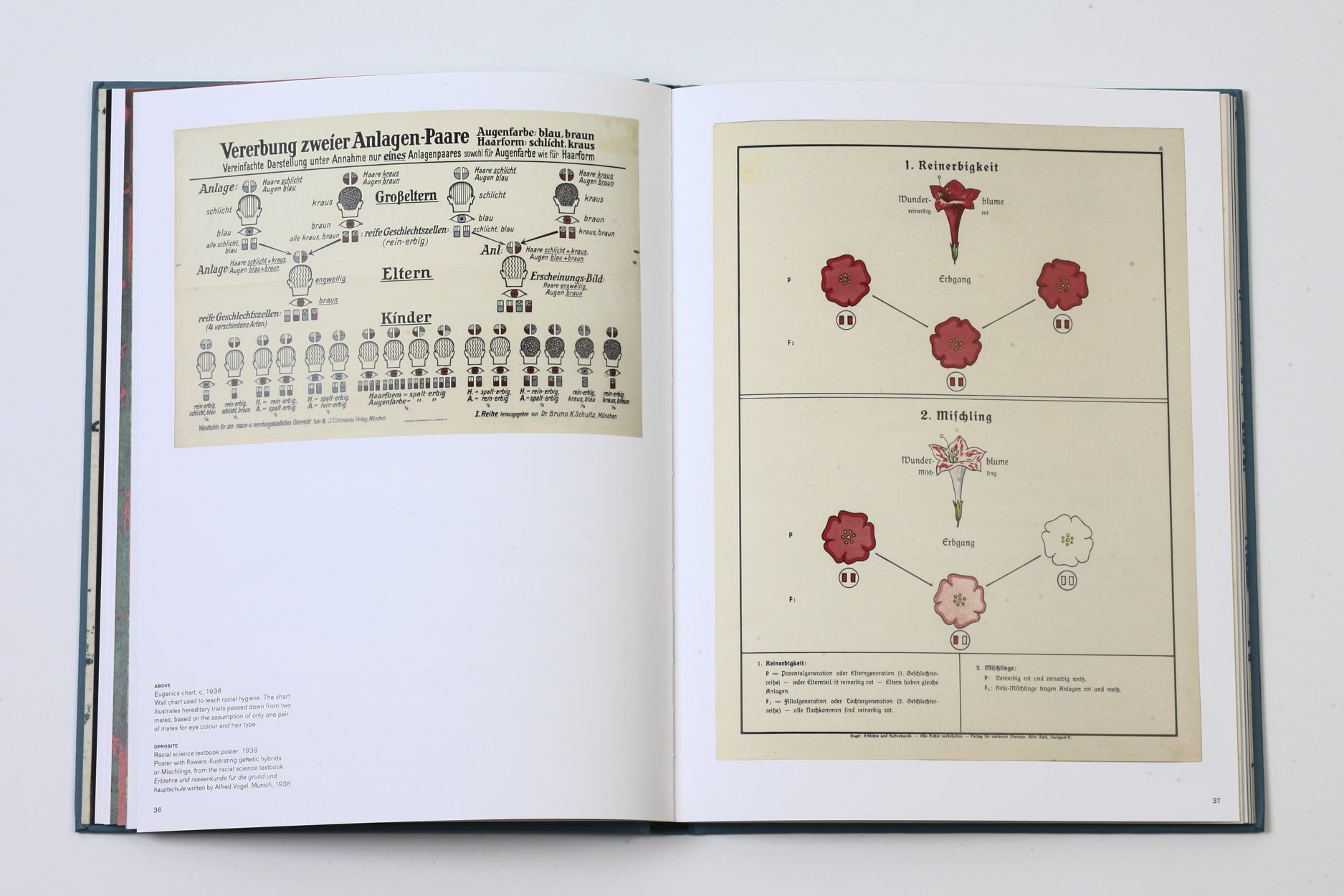

Mischling 1 shows the multi-faceted and complex research that Sara Davidmann engaged in as she came to learn about, process, and understand the fate of the German-Jewish side of her family. In this she uses images from the Davidmann family photo album in combination with artist-altered family photographs, contemporary photographic objects, texts written by the artist, and archival Nazi documents.

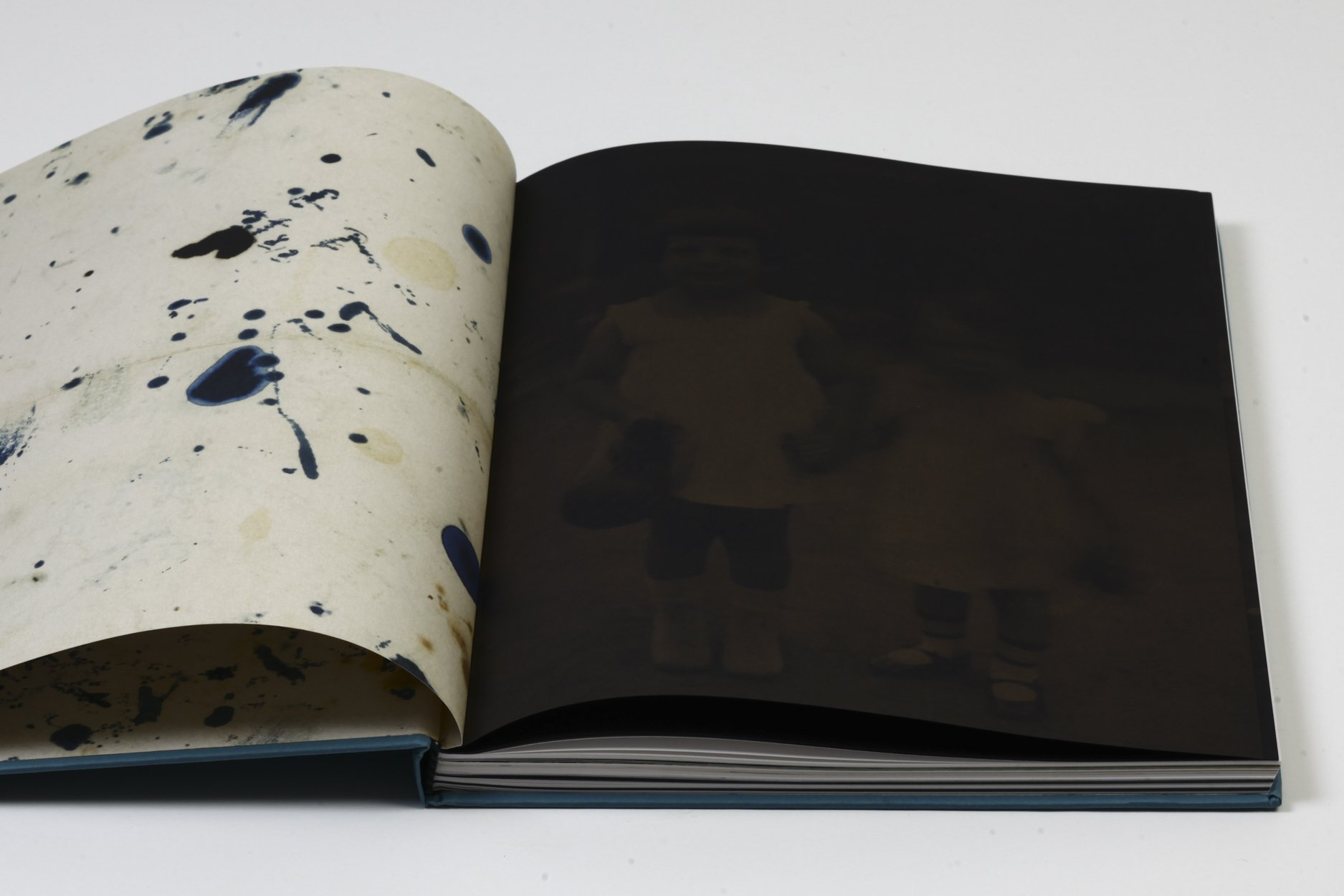

Upon opening the book we immediately enter into the artist’s family archive. The end sheets are her father, Mafred’s handwriting and mark making on blotting paper. A shade of deep indigo ink stains the pages in the form of blotches and scribbles. The lone fingerprint is one of the last remains of the hand which made the markings.

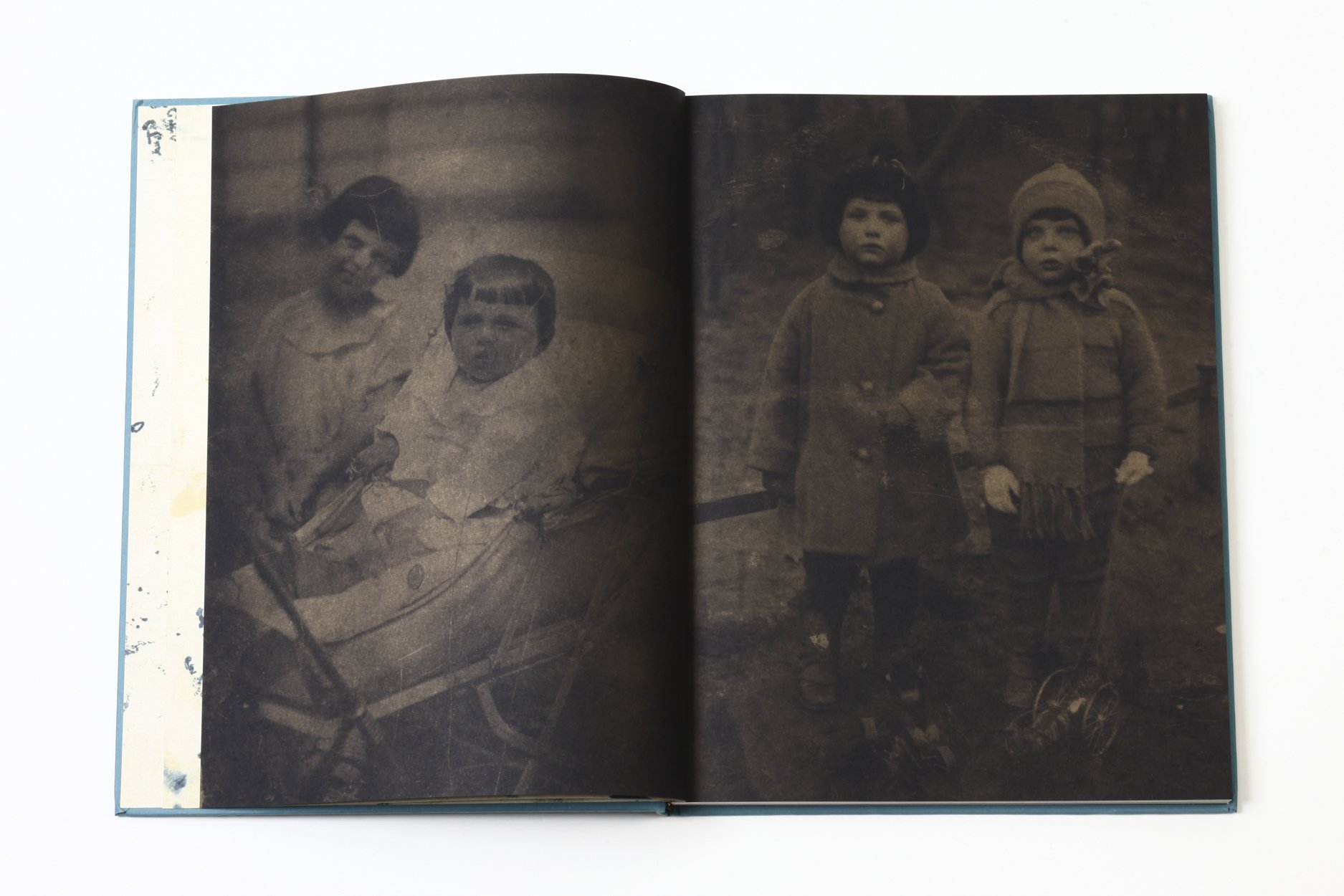

Next comes a series of darkened tintypes, which depict her family enjoying the green space at Humboldthain Park, much as families still do today. The images, made in 1925 and 1930 are dark and hard to see. But they are enlarged from their original size. The photographs were made across different seasons. In one image two children hold hands in sundresses and in another they are bundled in wool scarves and caps, snugly wrapped up against the chilly Berlin winter.

When I look at the children’s faces I am reminded of questions Marianne Hirsch, a scholar and writer on memory and post-memory, poses in a piece about Sara Davidmann’s work:

“When people are violently destroyed are not their earlier images also somehow marked by their fate? Can we look back at a pre-war moment without allowing our knowledge of what was to come circumscribe our vision?”

I look again. The children look scared in their rigid pose, their brows furrowed, unsmiling. Does the black paper the images are printed on foreshadow the dark fate of those inscribed with metallic ink? Is it me or them that feels the fear of their future?

Mischling 1 is a book the viewer must consume at their own pace. It takes time no matter how you endeavor to engage with it. While I approached this work with a broad knowledge base of Holocaust history and memory work as an artist, how many times over the last months have I shut the pages of this publication, stung by their contents? I spent time asking why this work was compiled into a book when it already existed on other platforms. Davidmann exhibited her work in a gallery and the project lives permanently on mynameissara.co.uk. Mischling 1, as a publication, puts art pieces and artifacts side by side in a way that an art gallery is not always capable of, blurring the lines between which is which, giving the viewer sharp reactions as they turn the page. There is a difference between learning and feeling. What makes Mischling 1 so thoughtfully published, I believe, is that it allows you to do both.

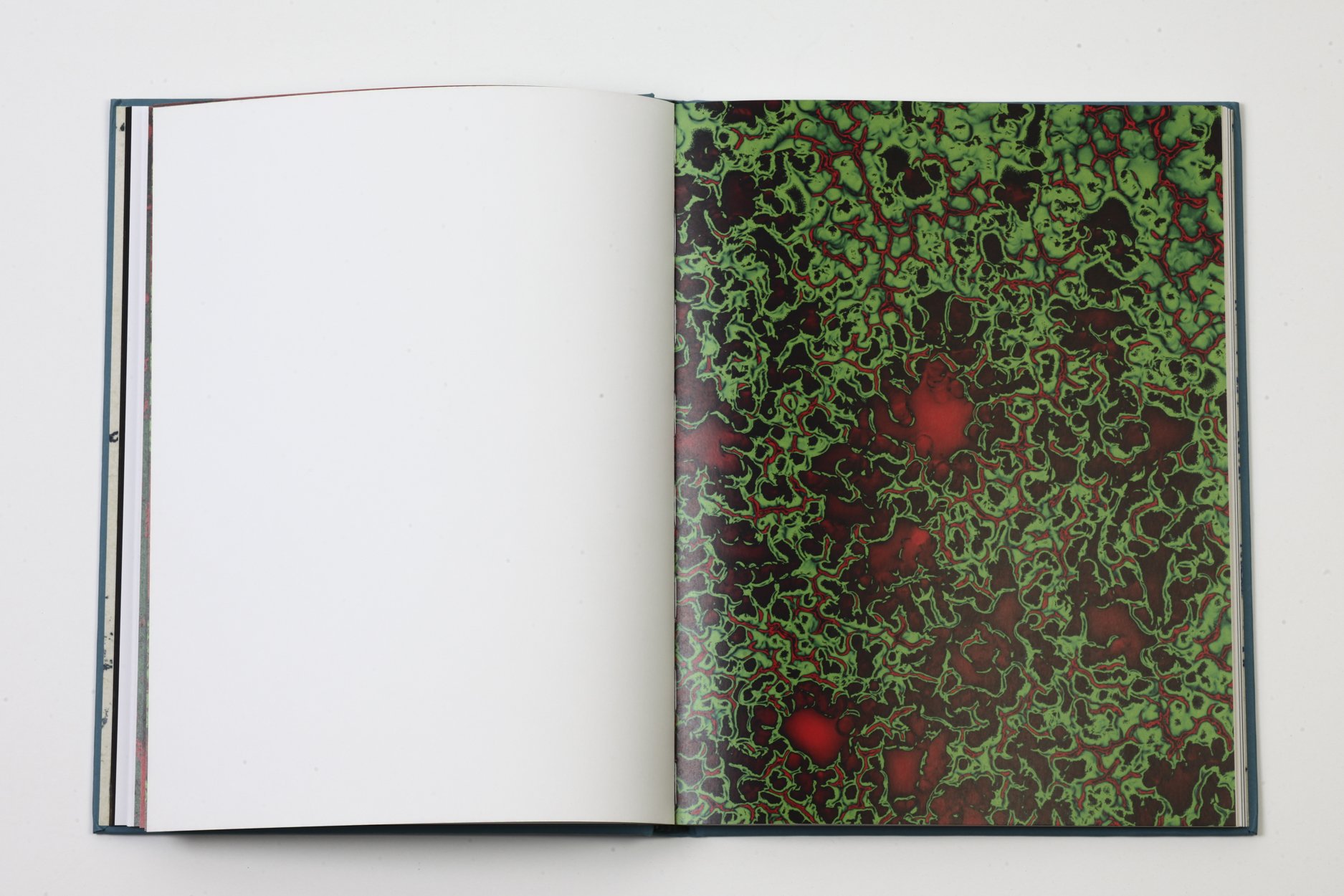

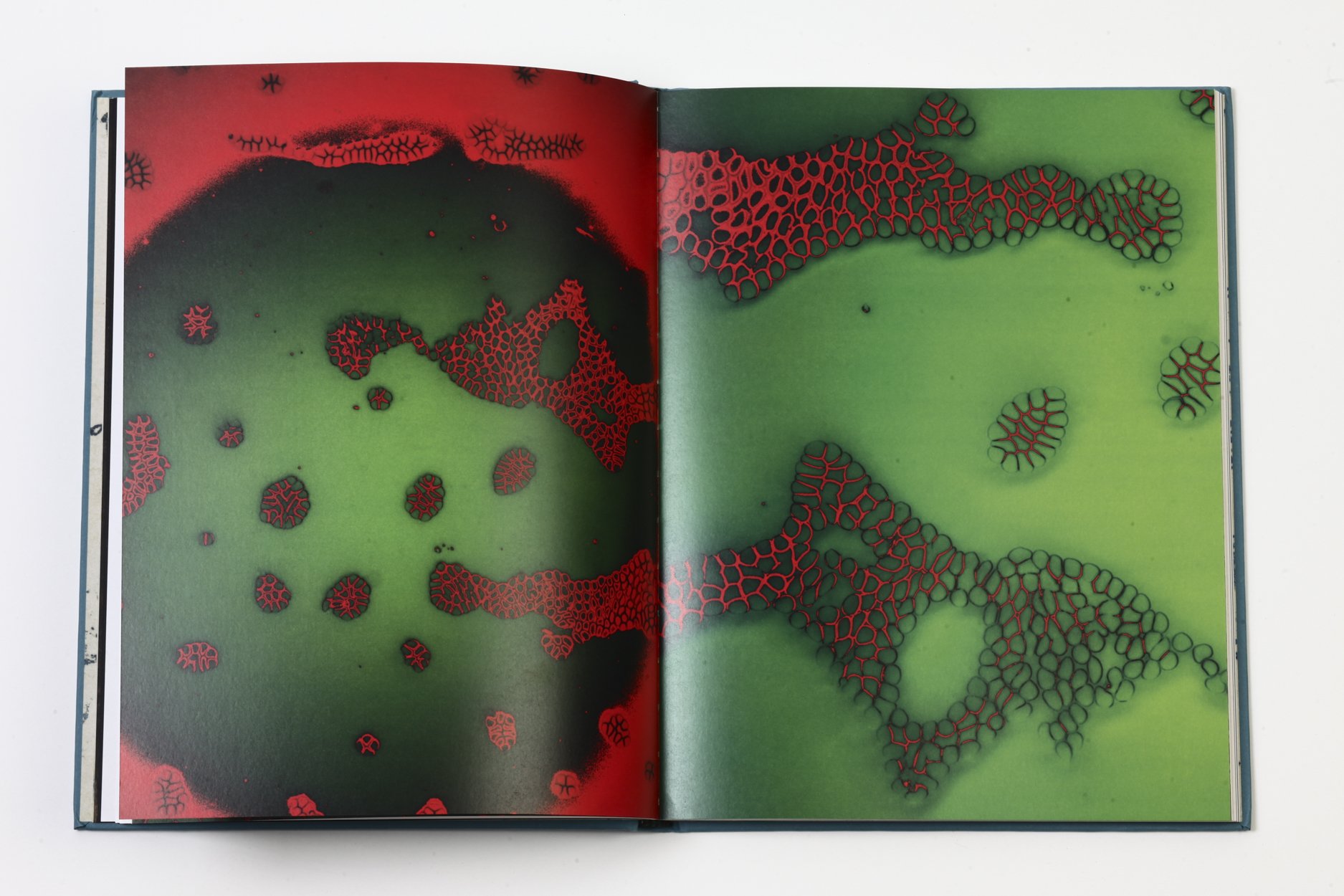

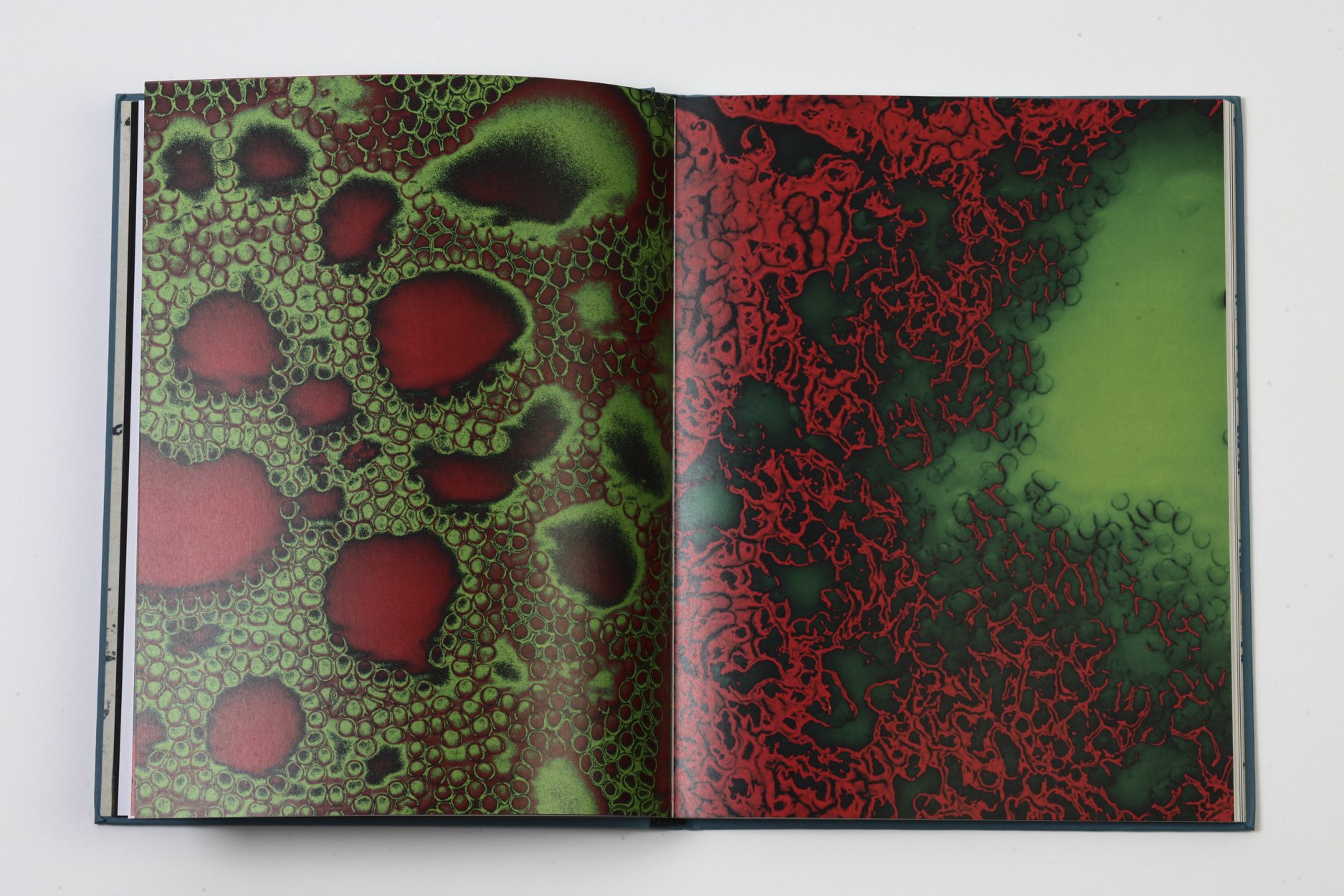

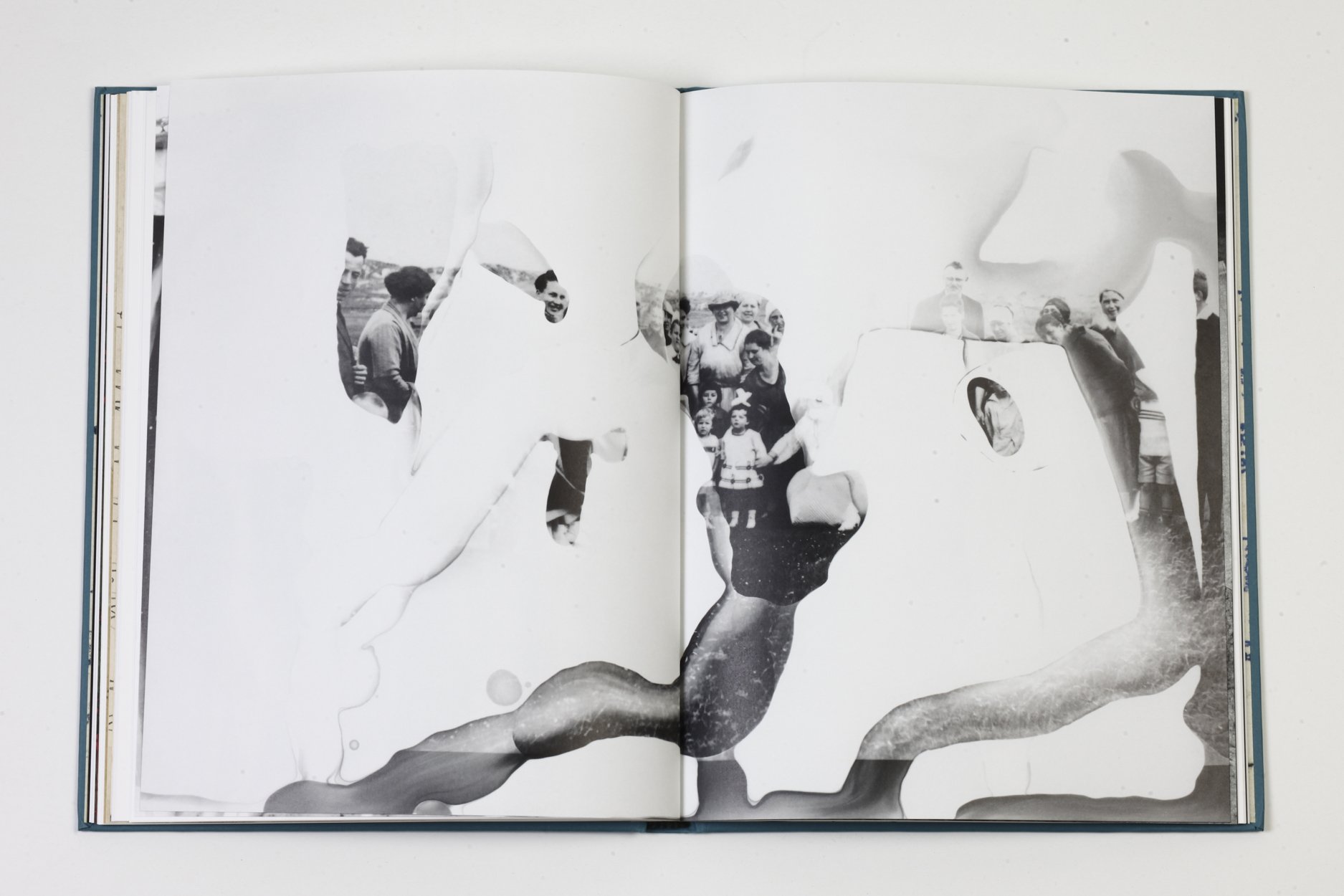

The first collection of Davidmann’s original artwork that we see within this book appears to be vast pools of unknown, unrecognizable substance.The liquid landscapes of red and green texture engulf the viewer. We learn that these are a series of microscope photographs of the blood of her living family members. Upon turning the page the viewer is confronted with the cold, lifeless document, Gesetz zum Schutze des deutschen Blutes und der deutschen Ehre (Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour). It's jarring to linger within textures then turn the page to a cold document. The juxtapositions within the sequencing and the effect they have on the viewer are successful.

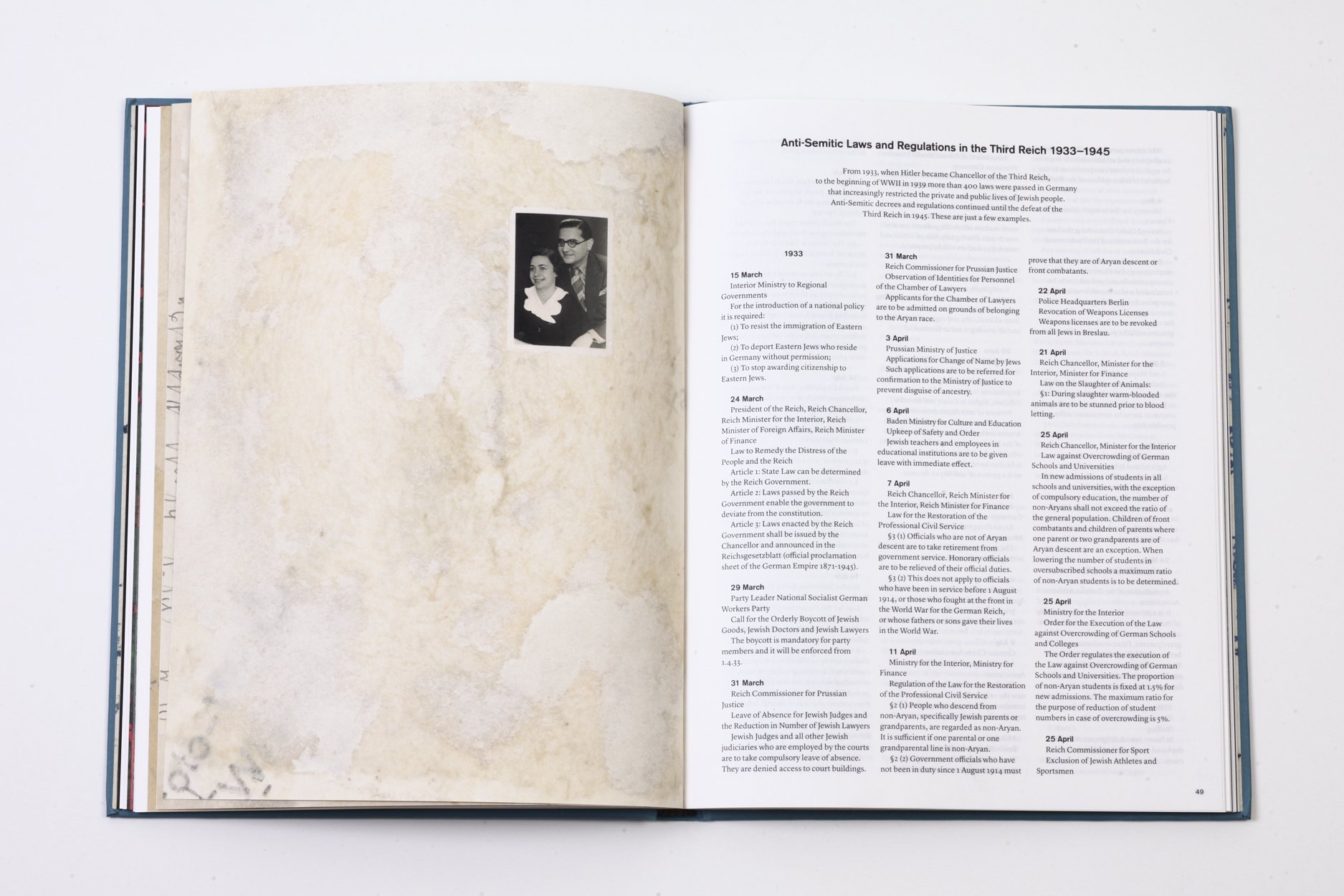

When Davidmann visited archives she chose to photograph, rather than scan the objects she viewed. This decision allows the viewers to see the object-qualities of the documents. We see their shadows as well as the tears in the paper and indentations from a typewriter. The color palette rarely changes as we flip between documents and reproductions of the family album. It is interesting that the paper which holds the family memories aged and faded to become a similar tone as the documents. In the middle of these strikingly normal photographs of family, school, and life in Berlin, the viewer is assaulted with the text of the Nuremburg laws, anti-Semitic policies implemented by the Nazis beginning in 1933. Here, you learn. From one law to the next you see how insidiously the lives of Jewish communities in Germany crumbled.

I want to ponder the original photo album for a minute and think about the woman who put it together. A family album, like the object that started this journey, is a site of memory. Davidmann’s aunt Susi was a 17 year old girl when she was displaced from her home, carrying with her real and true memories of the places she left and the people she and her brother Manfred left behind. Why did she put this object together? Was it as a way to remember? Who was it that chose to pack the photographs before she boarded the kindertransport that saved their lives? The captions can be shocking, such as “Omi Dorothea, just before the Gestapo took away and murdered her, 1941.” Later we find out the captions were written by Susi herself.

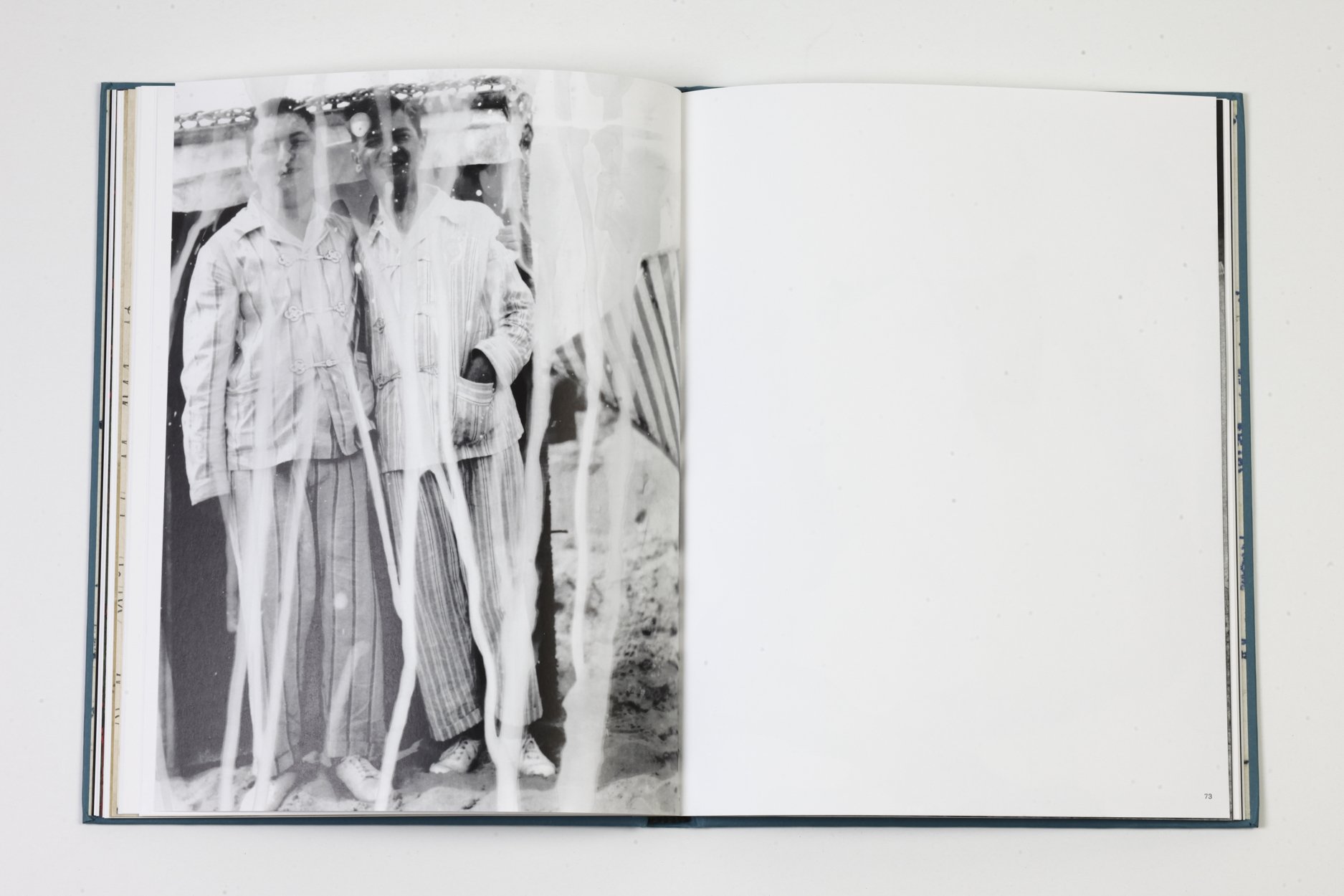

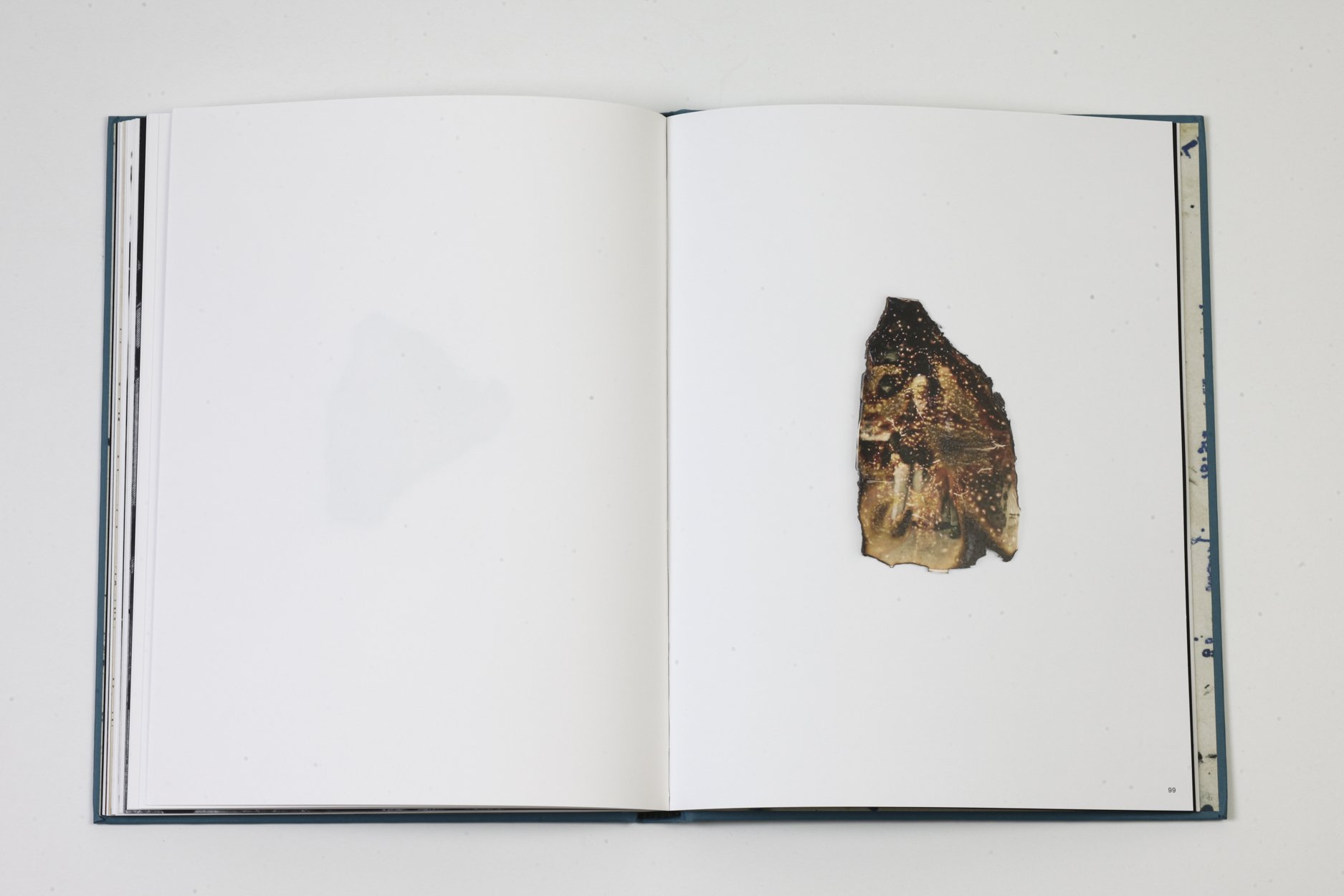

The medium of photography itself is significant throughout this work. Many works about the Holocaust tread an uncomfortable line of aestheticization. Davidmann’s project does not do that. She utilizes her own blood in a number of the developing processes she engages in. In this way she inserts herself into family history. The altered images contained within Mischling 1 can make you uncomfortable. While you can get lost in their succulent, photographic medium such as the chemical drips of the darkroom developer or the scorched edges, they can also make your blood churn and your skin prick.

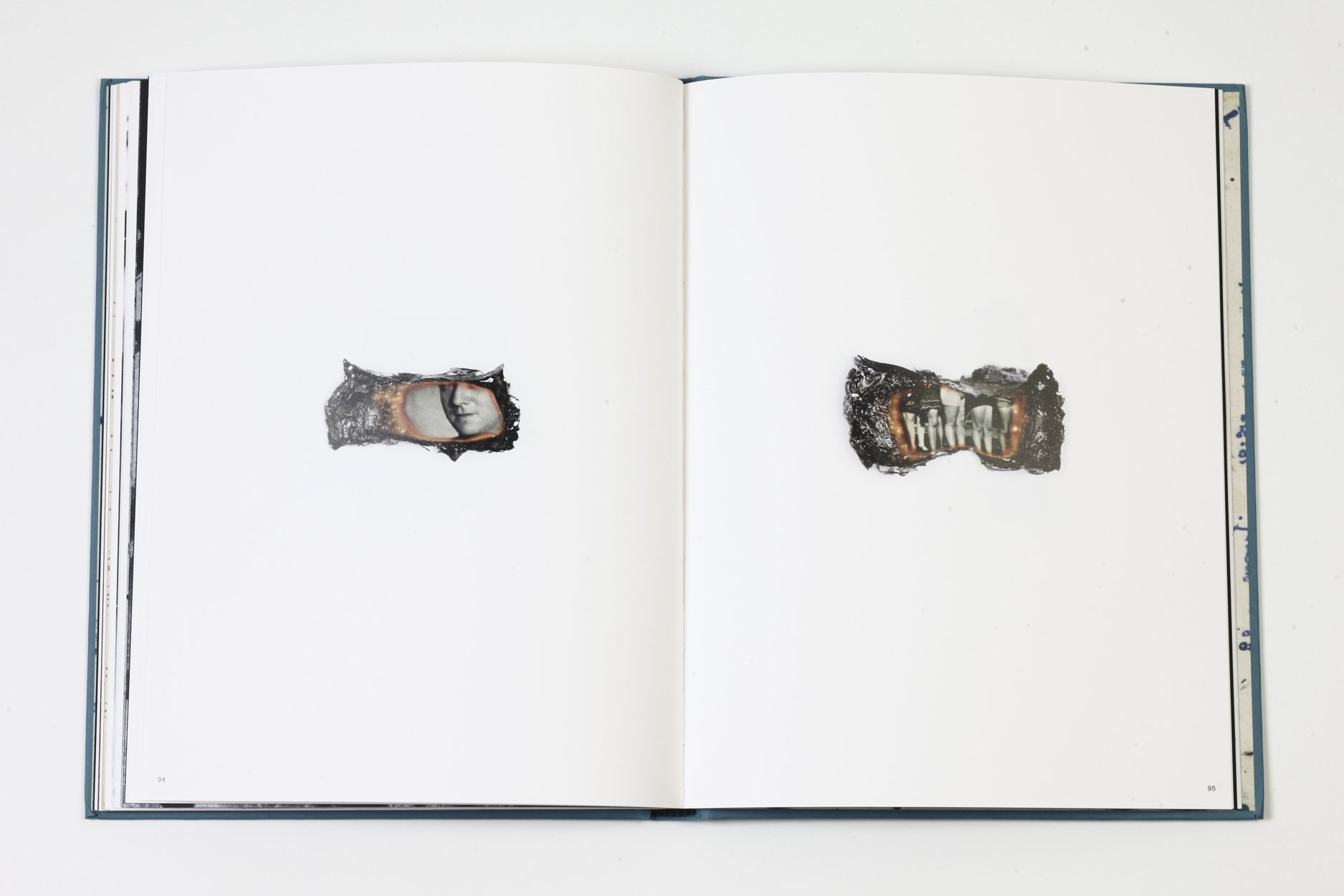

The series “Remains'' consists of burnt photographic objects. I struggle with the significance of working with reproductions. Although photography, at the root of the medium is reproducible, wouldn't burning the actual objects truly be a more accurate parallel? Why is there anything left? But Davidmann chose not to perform the same acts as the perpetrators, fire as a means of total erasure. So while my initial impression was that the work doesn’t go far enough, with contemplation they became the most emotionally evocative. The photographs are melted and distorted. Faces become lost in the scattered light of destruction. In the same ways that we can see our ancestors in ourselves, the remains of the burnt photographs reveal only fragmented details of the people they once represented. Does Sara recognize herself in these fragments?

Sara Davidmann ends the book with a plea and an understanding that the hatred that caused the Holocaust still courses through society today. She ends with statistics about anti-Semitic acts, which unfortunately have not ceased, and the level of ignorance amongst young people around this history today. I think about the time that has passed between the atrocities of the Holocaust and today, and how important maintaining a knowledge of the past is. We need to remember this history and works such as this are a reminder.

“As Britain, Europe and America see a rise in right-wing rhetoric and populism, and vast numbers of refugees continue to flee to escape genocide… I cannot help but wonder what will happen if we do not listen to these alarm calls and learn from our past.” - Sara Davidmann

Sara Davidmann is a multi award-winning artist/photographer. For 14 years (1999-2013) Sara took photographs and carried out oral history recordings in collaboration with people from UK transgender and queer communities. Self-representation, trans relationships and families were a focus of this work.

For over a decade (2011- ) Sara’s work has focused on her own family. This work has achieved considerable national and international recognition. Sara’s last project, ‘Ken. To be destroyed’ was exhibited in Berlin, Victoria B.C., Mumbai, London, Liverpool, and Belfast. It was the focus of three events at the Victoria & Albert Museum and was published as a monograph, edited by Val Williams (Schilt 2016). Sara’s artworks are regularly published in books and journal articles. She has received numerous awards for her work including a Philip Leverhulme Prize, a Fulbright Hays Scholarship, four Arts and Humanities Research Council awards, an Association of Commonwealth Universities Fellowship and a Wellcome Trust grant. She is Reader in Photography at University of the Arts London and has a PhD in Photography from London College of Communication.

Michling 1 is available from GOST Books.