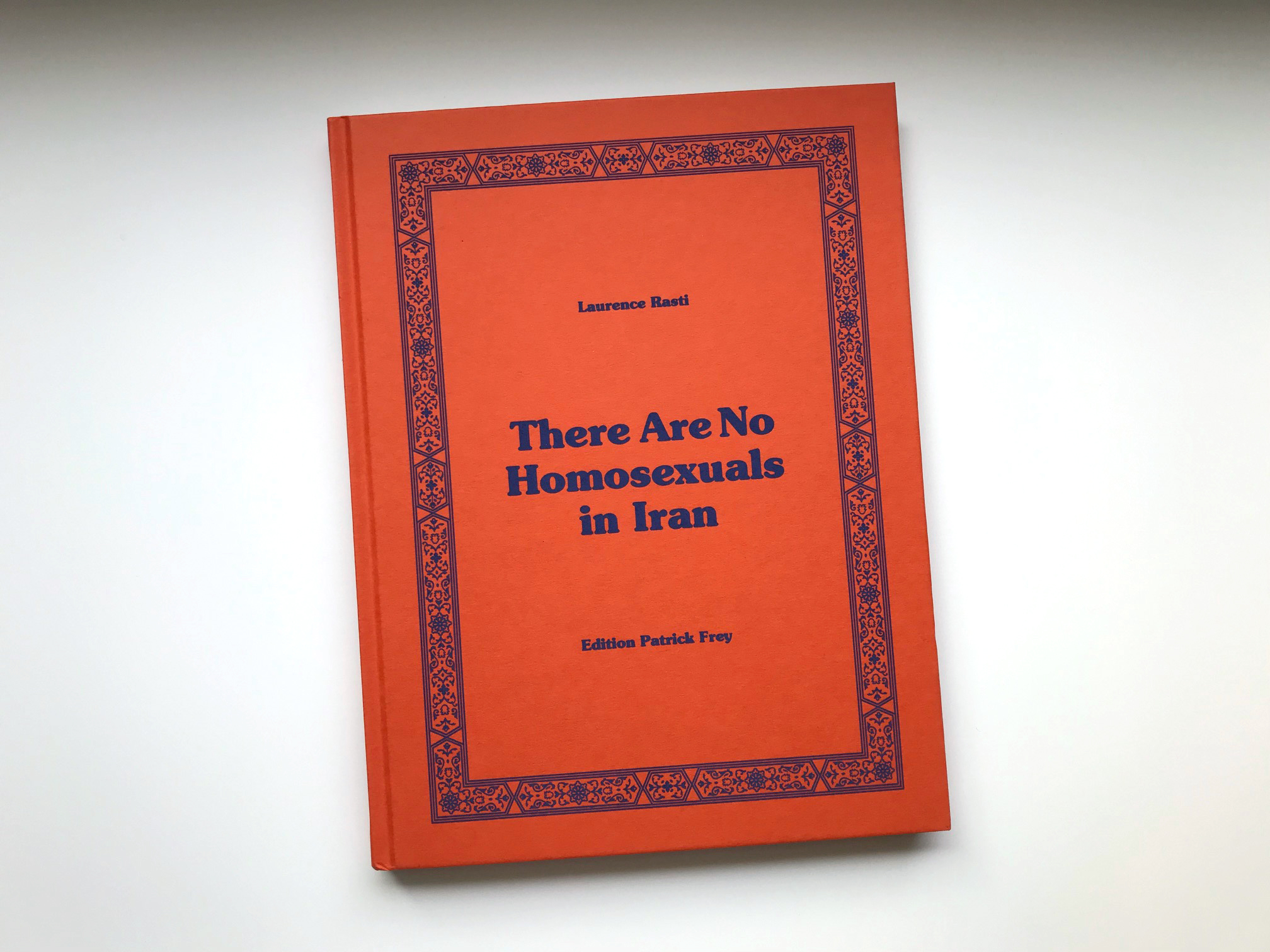

Book Review: Laurence Rasti’s “There are no homosexuals in iran”

By Jess T. Dugan | September 19, 2018

Published by Edition Patrick Frey / 7.5 in. x 10 in. / 156 pages / 53 images

Printed in Germany in an edition of 700 / First edition 2017, second edition 2018

Laurence Rasti’s book There Are No Homosexuals In Iran, published by Edition Patrick Frey in 2017, is titled after a comment made by the Iranian president at the time, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, while speaking at Columbia University on September 24, 2007: “In Iran, we do not have homosexuals like in your country.” Rasti, who was born to Iranian parents in Geneva, Switzerland in 1990, explores ideas of identity, gender roles, and beauty through her photographs, which are informed by her dual Swiss and Iranian background.

The introduction to There Are No Homosexuals In Iran sets the stage for the work that will follow:

Speaking at Columbia University on September 24, 2007, Iranian president at the time Mahmoud Ahmadinejad proclaimed: “In Iran, we do not have homosexuals like in your country.” While most Western nations now officially accept homosexuality and some even same-Sex marriage, homosexuality is still punishable by death in Iran. Homosexuals are not allowed to live out their sexuality there. Their only options are either to choose transsexuality, which is tolerated by law but considered pathological, or to flee. In Denizli, a city in Turkey, hundreds of gay Iranians are stuck in a transit zone, their lives on hold, hoping against hope to be welcomed into a host country someday where they can start afresh and come out of the closet. Set in this state of limbo, where anonymity is the best protection, my photographs explore the sensitive concepts of identity and gender and seek to restore to each of these men and women the face their country stole from them.

The book begins with interview texts from some of the individuals Rasti photographed, providing a more in-depth understanding of the struggles faced by LGBT Iranians (who most certainly exist, of course, despite Ahmadinejad’s comment declaring otherwise). The interviews are identified using first names, but they are separated from their corresponding portraits, creating a sense of anonymity that is central to this project and book. The stories are difficult, outlining lifelong struggles and impossibly difficult choices, such as having to leave a loved one behind in order to seek safety in another country. But, despite this, there is also a sense of hope that a better future is possible, albeit only elsewhere.

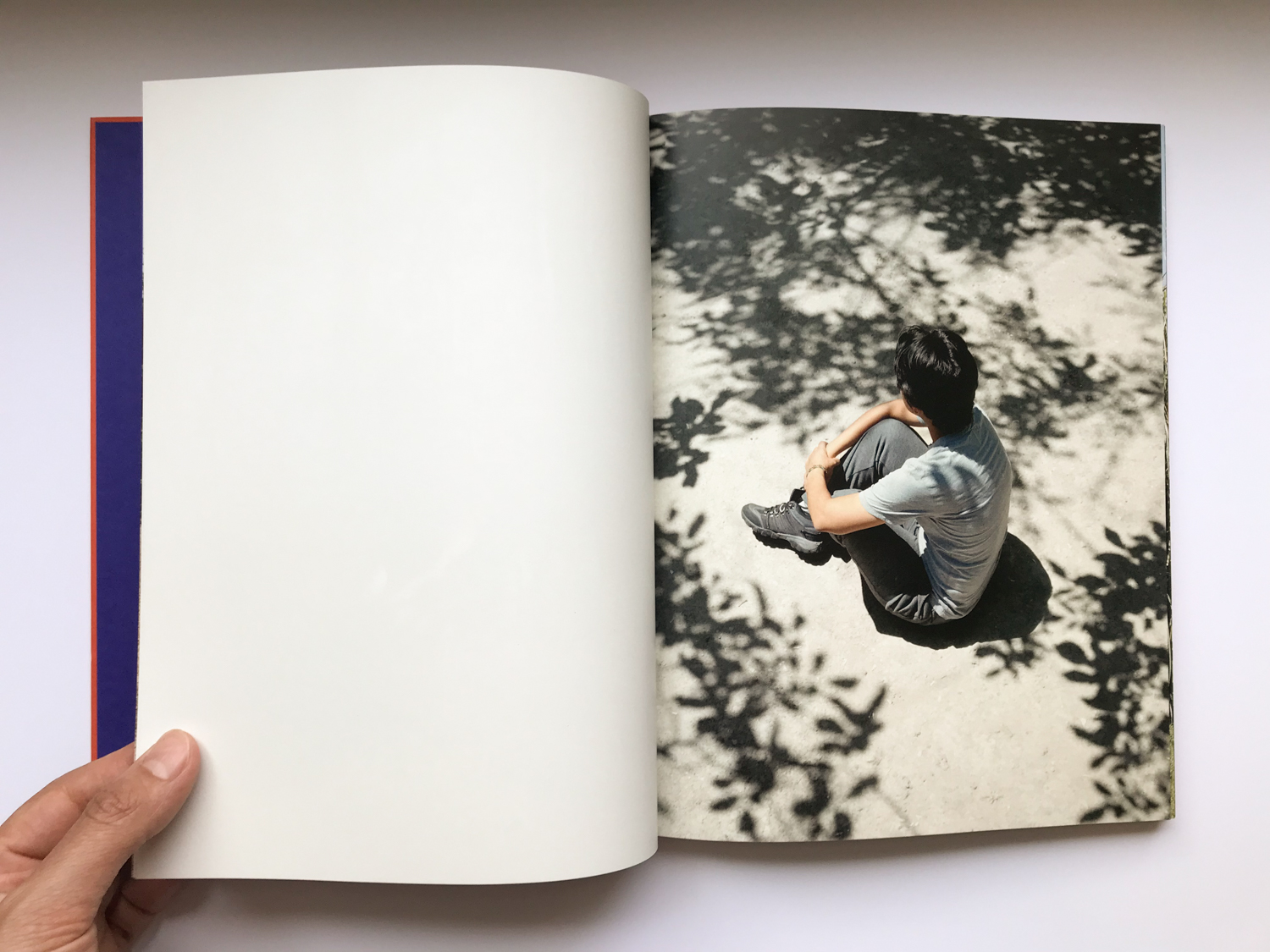

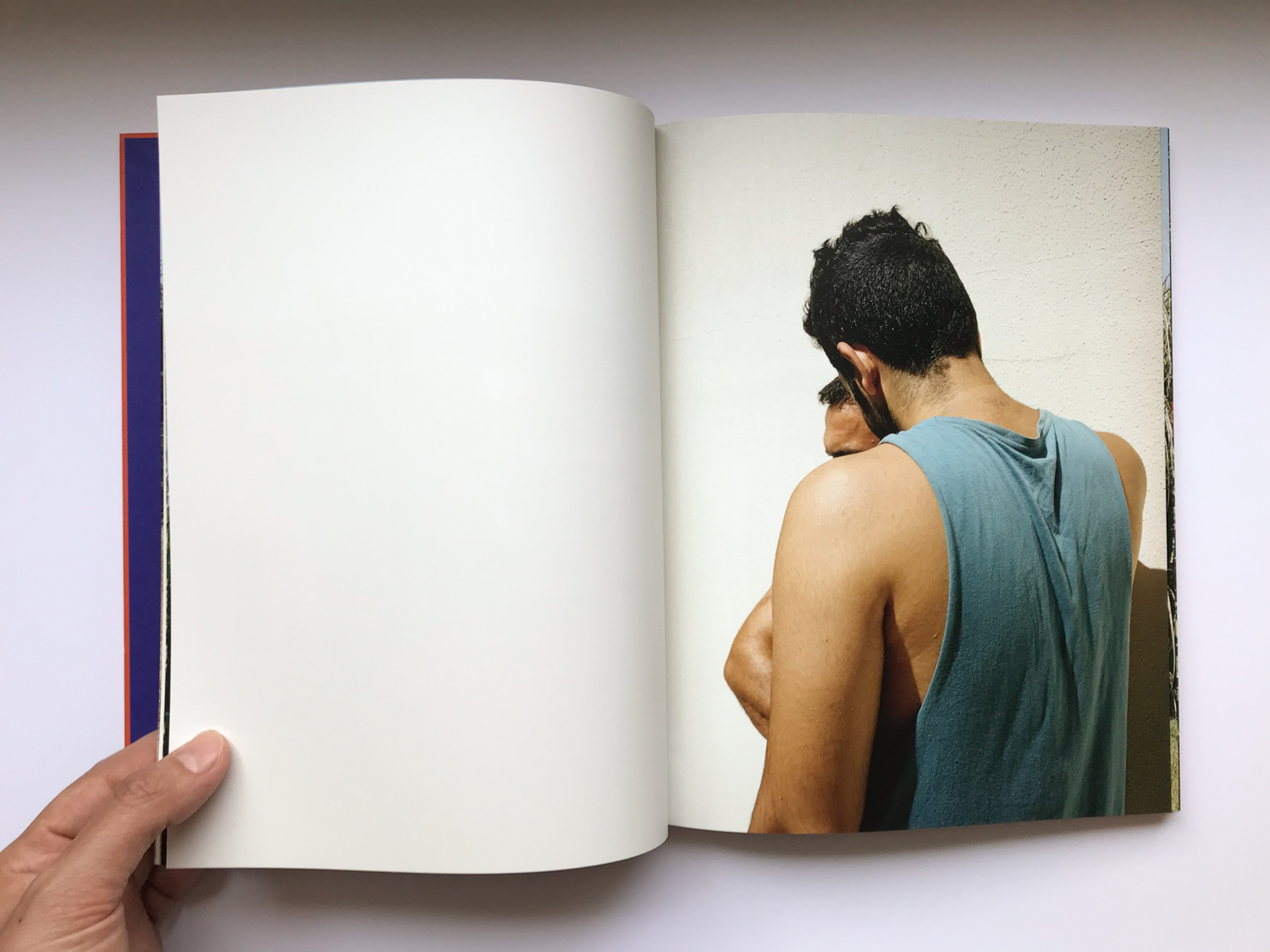

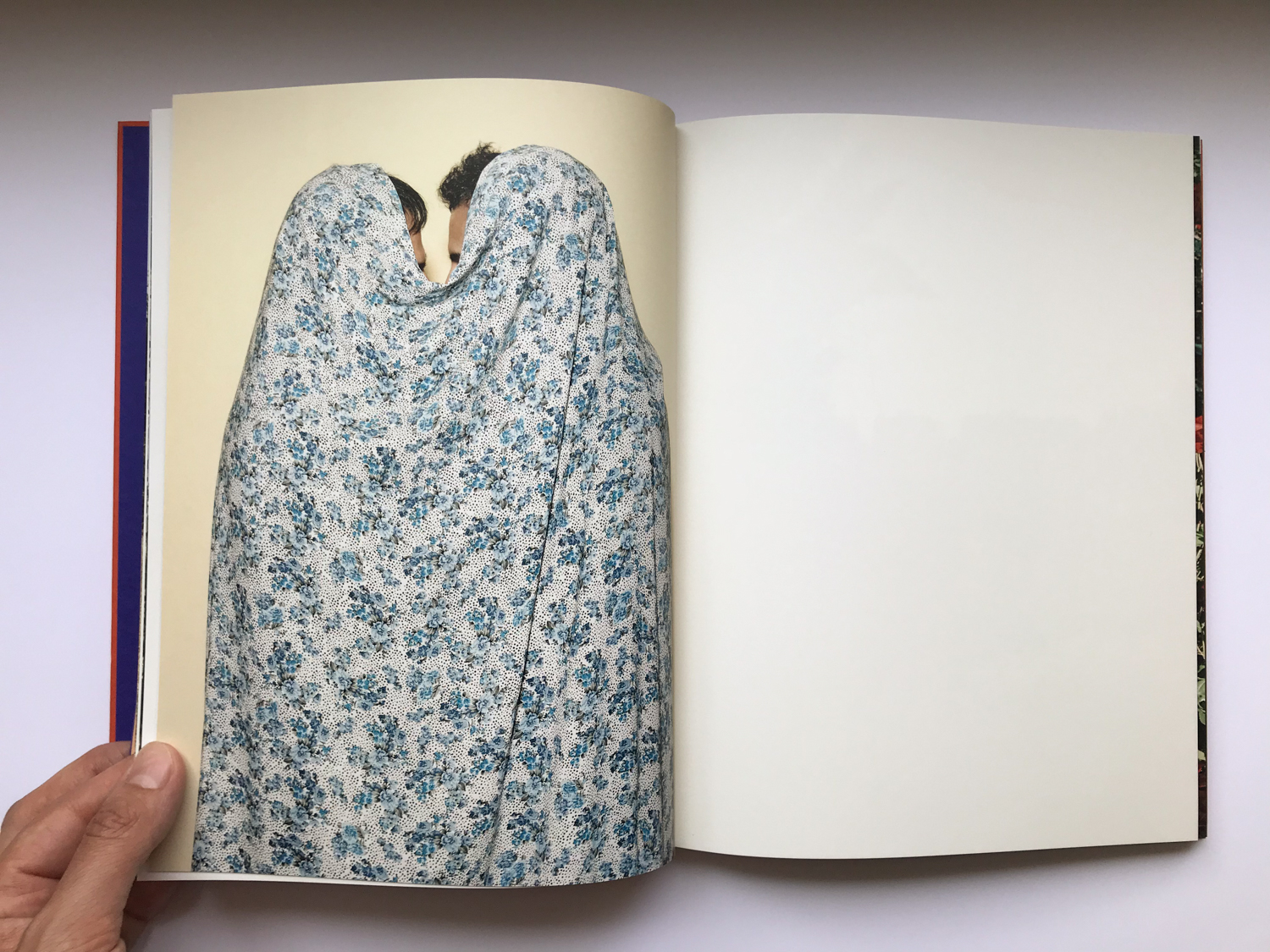

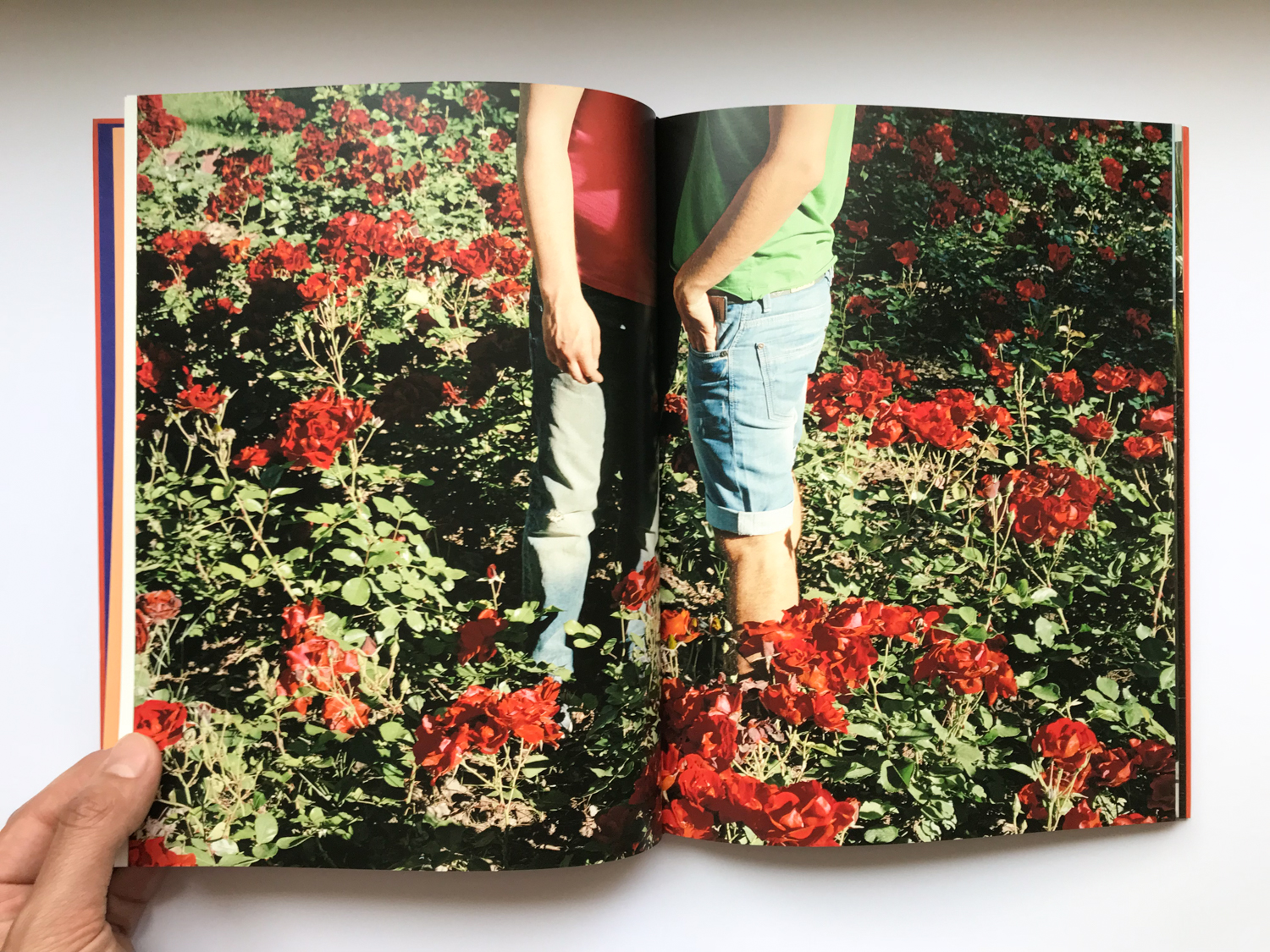

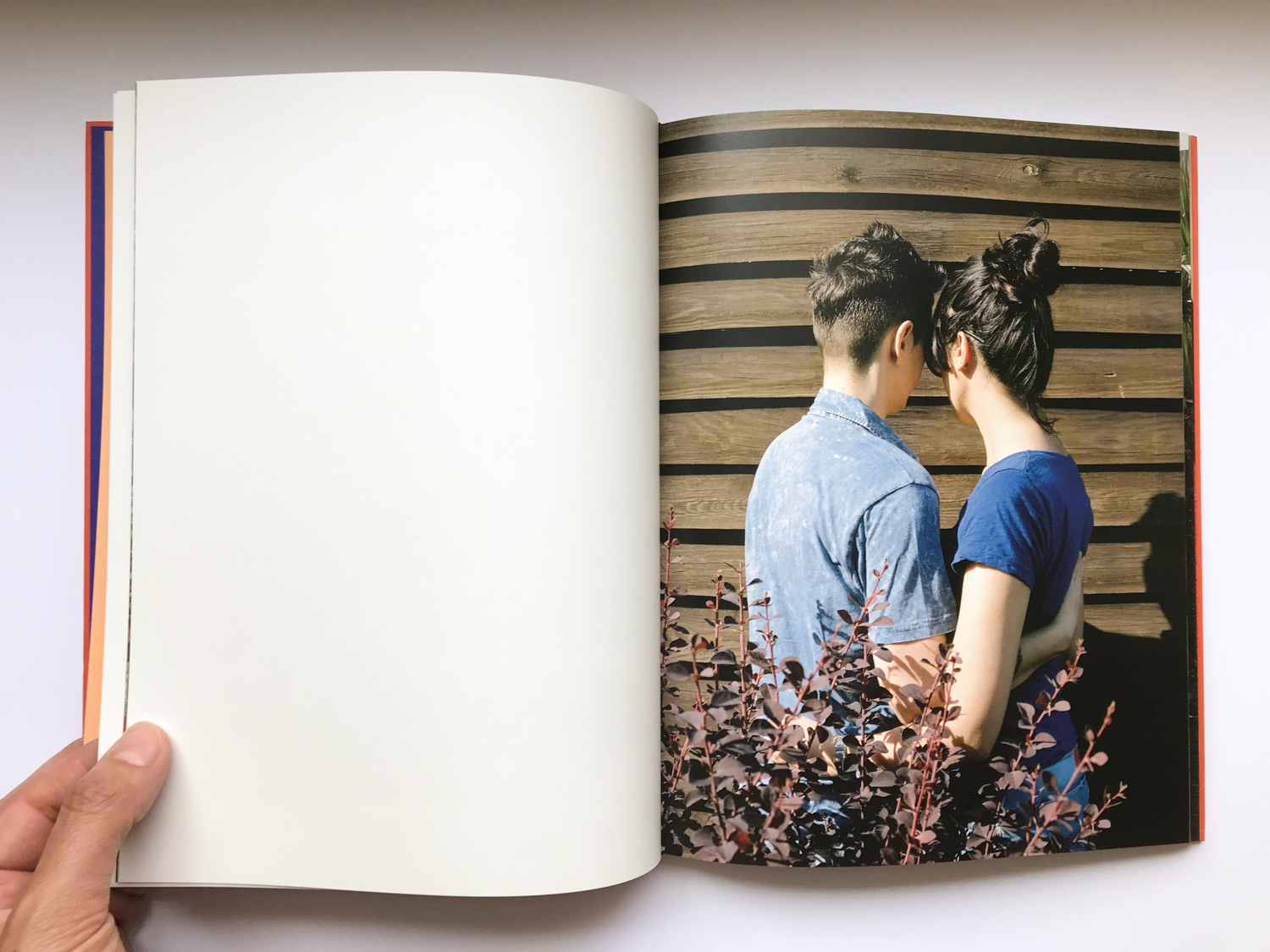

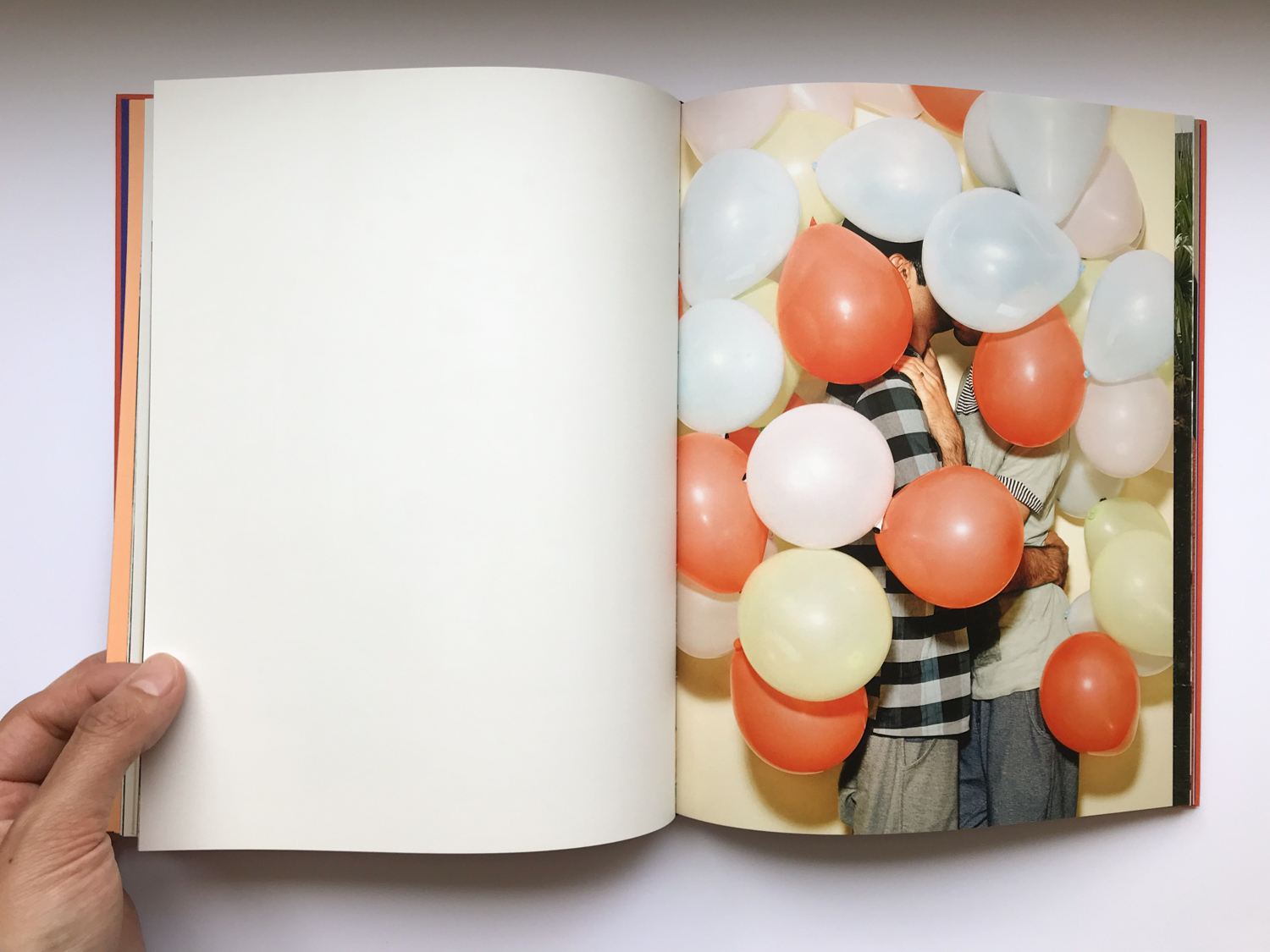

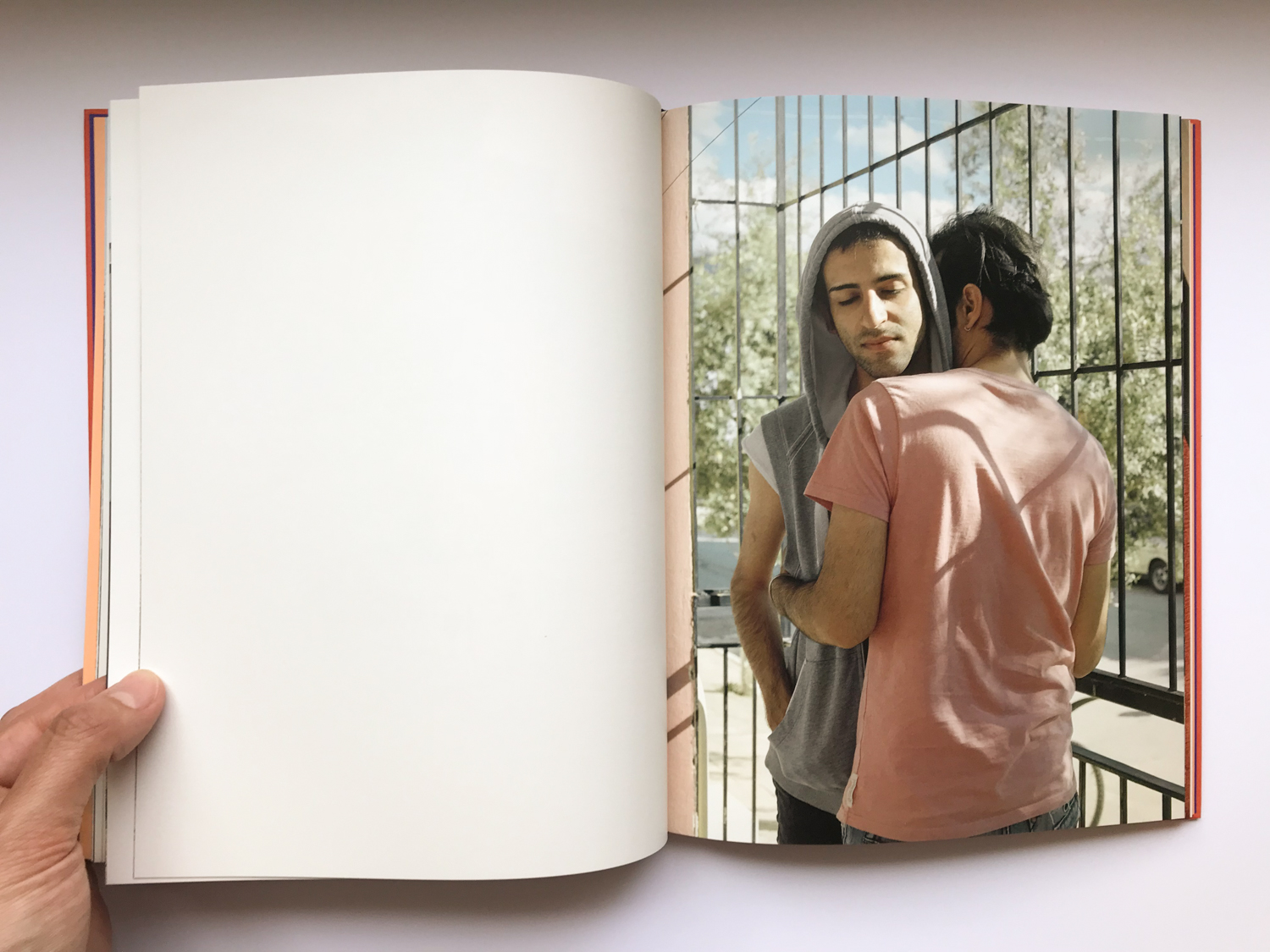

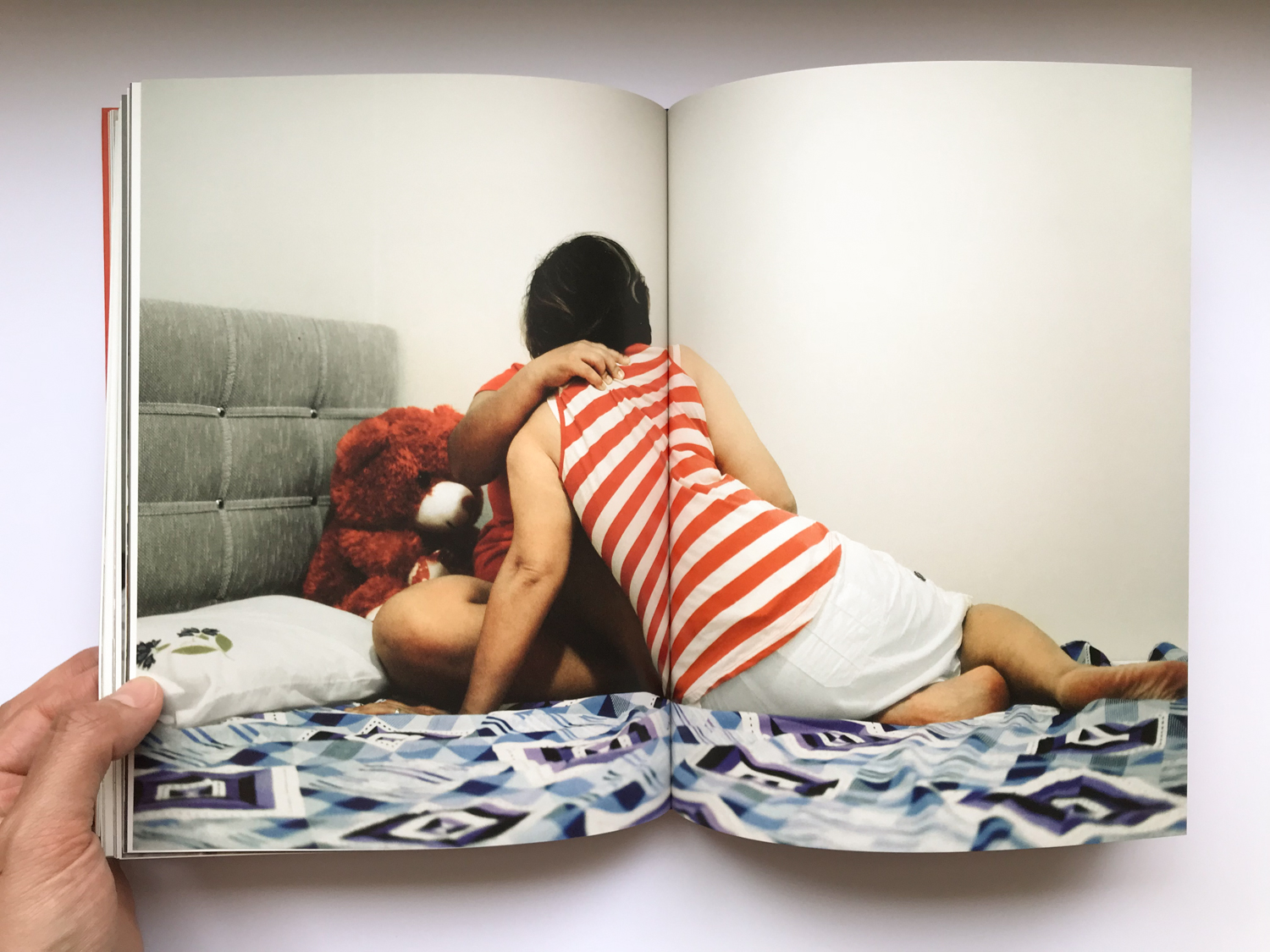

I am always fascinated by portraits that do not depict the faces or identities of the person in them, as that is what we so often rely on to create a connection with others through portraiture. Many of Rasti’s images, out of concern for the subjects’ privacy, depict individuals and couples from behind or obscured by objects such as balloons, trees, flowers, blankets, clothing, or each other’s hands or bodies. There is even, in one image, a pair of cats, held up playfully in front of the subject’s face, adding a sense of humor to a difficult topic. Rasti also included environmental images that provide more contextual information about the place where her subjects live, although it is the portraits that I find the most compelling.

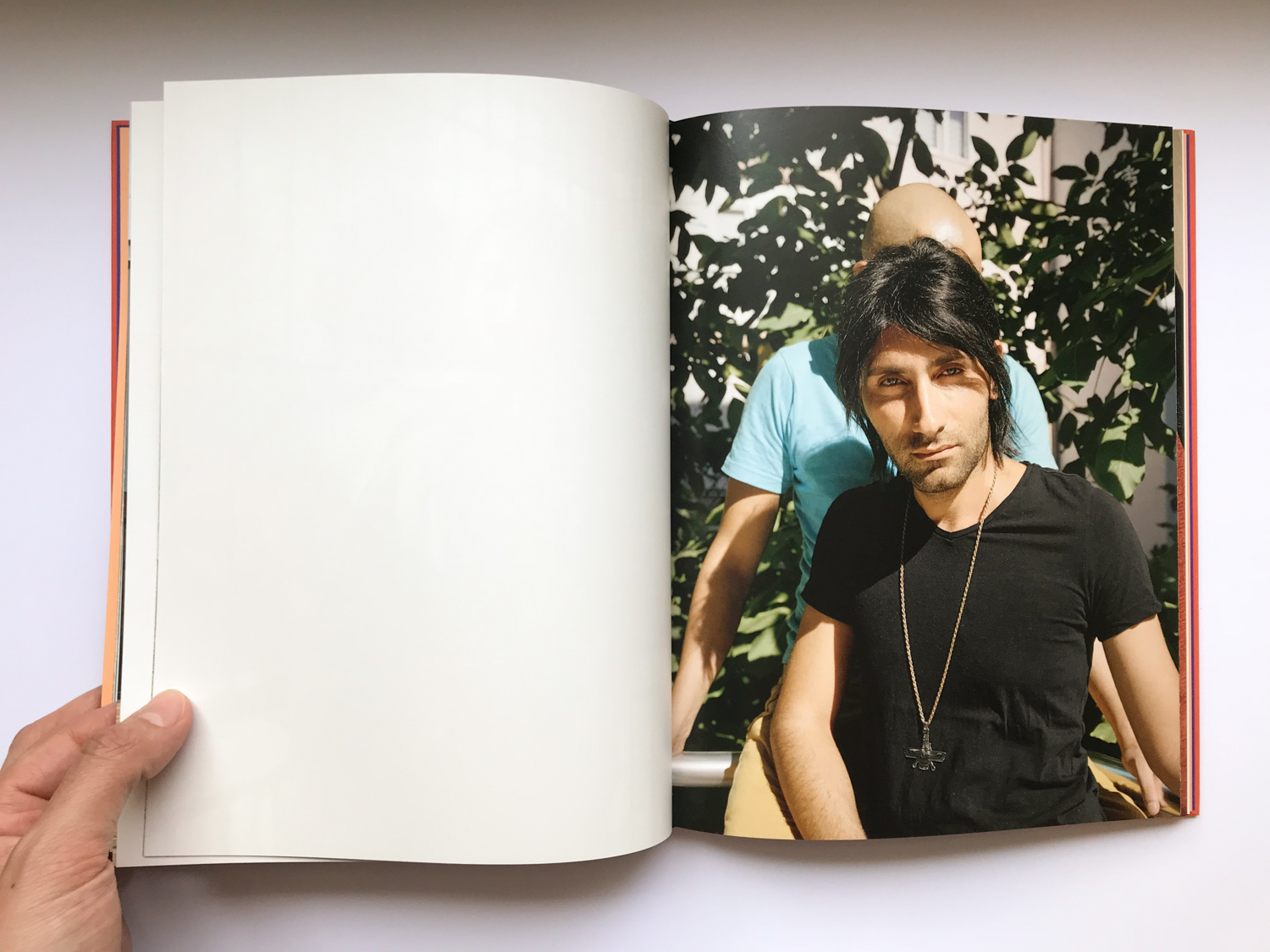

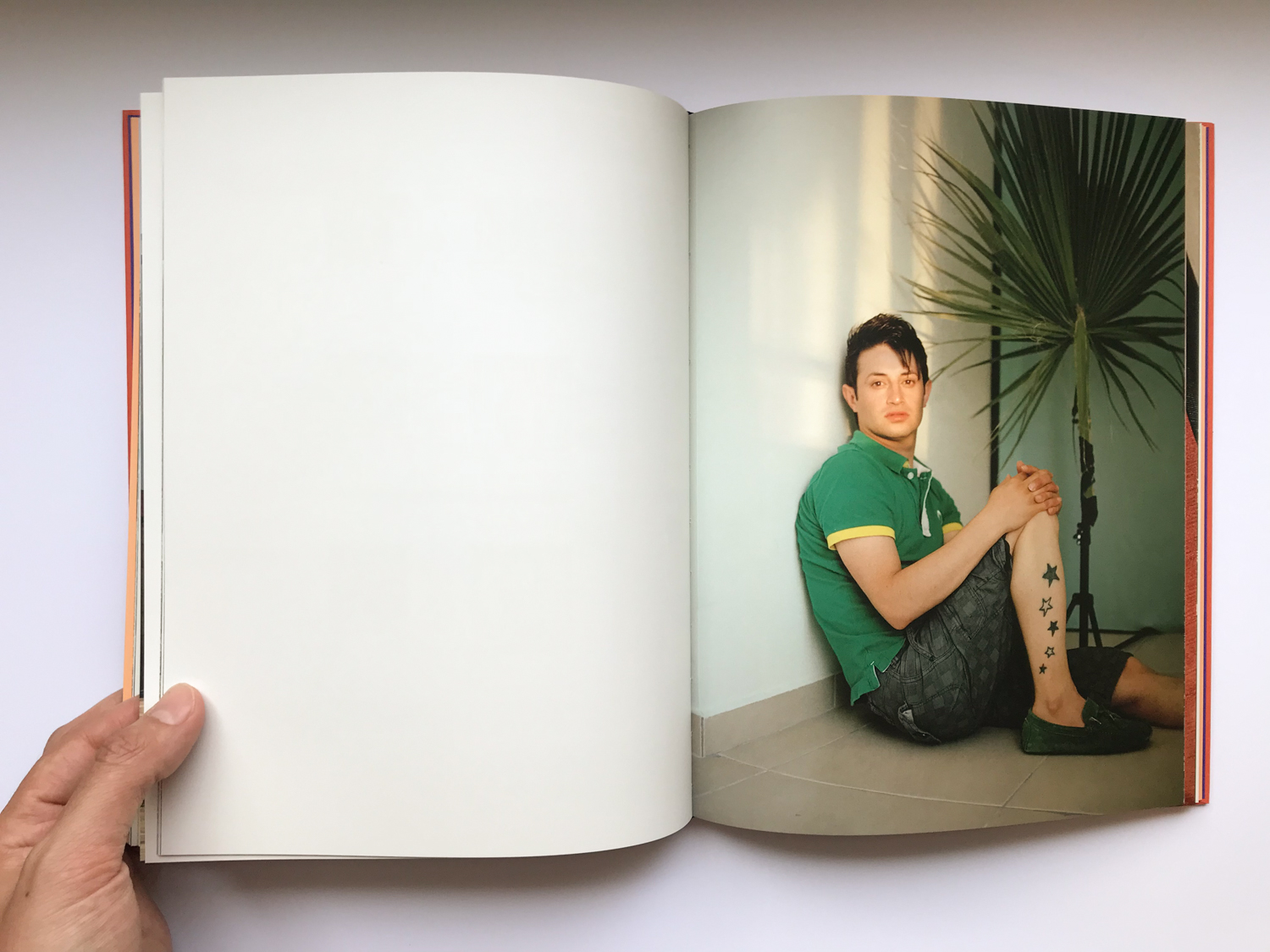

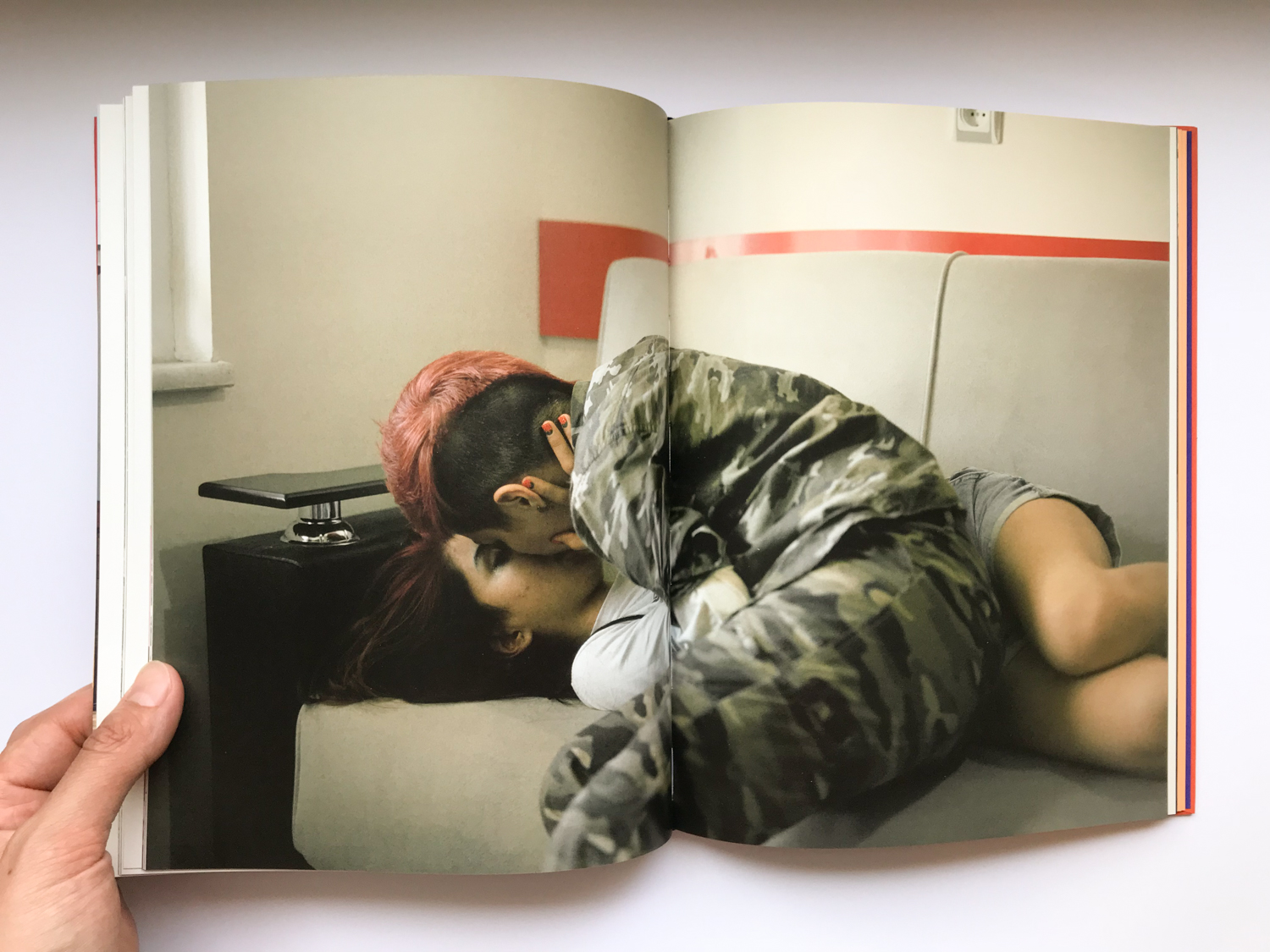

The subjects in the beginning of the book are almost all turned away from the camera, their identities obscured, but as you turn the pages, you begin to see their faces. They reveal more and more of their identity as the book progresses, posing together as couples or in gender transgressive clothing. The result of this sequencing decision is that the book is imbued with a sense of hope and progress, as if things are moving in a better direction where individuals could be free to be themselves without fear of violence, discrimination, or even death. Coming from a Western perspective, it is difficult to fully comprehend the level of risk involved in living openly or sharing one’s identity in such an oppressive place, but this knowledge makes the revealing portraits all the more powerful.

There is a tenderness in Rasti’s photographs; it is clear she has the trust of her subjects, who are in a vulnerable position. There is also a sense of playful collaboration running throughout the book, and a kind of lightness and openness to the photographs themselves, which provides a conceptually interesting counterpoint to the difficult nature of the subject. This book is powerful, and the individuals who have entrusted Rasti with their stories are participating in gestures of activism to make their world a better place.

Interestingly, when my copy of the book arrived in the mail, it had a sticky note attached to it with the words “yes there are” scribbled on it. I initially wondered if this was a part of the book itself, but after asking around and learning that not all copies arrived with such a note, I realized that someone who handled the book along its shipping path had misinterpreted the book, not realizing the source of its title or the meaning of its contents, and had inserted a quiet gesture of activism. It is this spirit of pushing back, of working to change society to be more just and free, that runs through the book and imbues it with the assurance that no matter the obstacles, and often at great cost, individuals will always find a way to be themselves.