Book Review: “TEMPLE OF THE SELF” by LAUREN NOELLE OLIVER

By Keavy Handley-Byrne | December 9, 2021

Published by Monolith Editions in 2020

Softcover / 9.5 x 7 inches / 48 pages

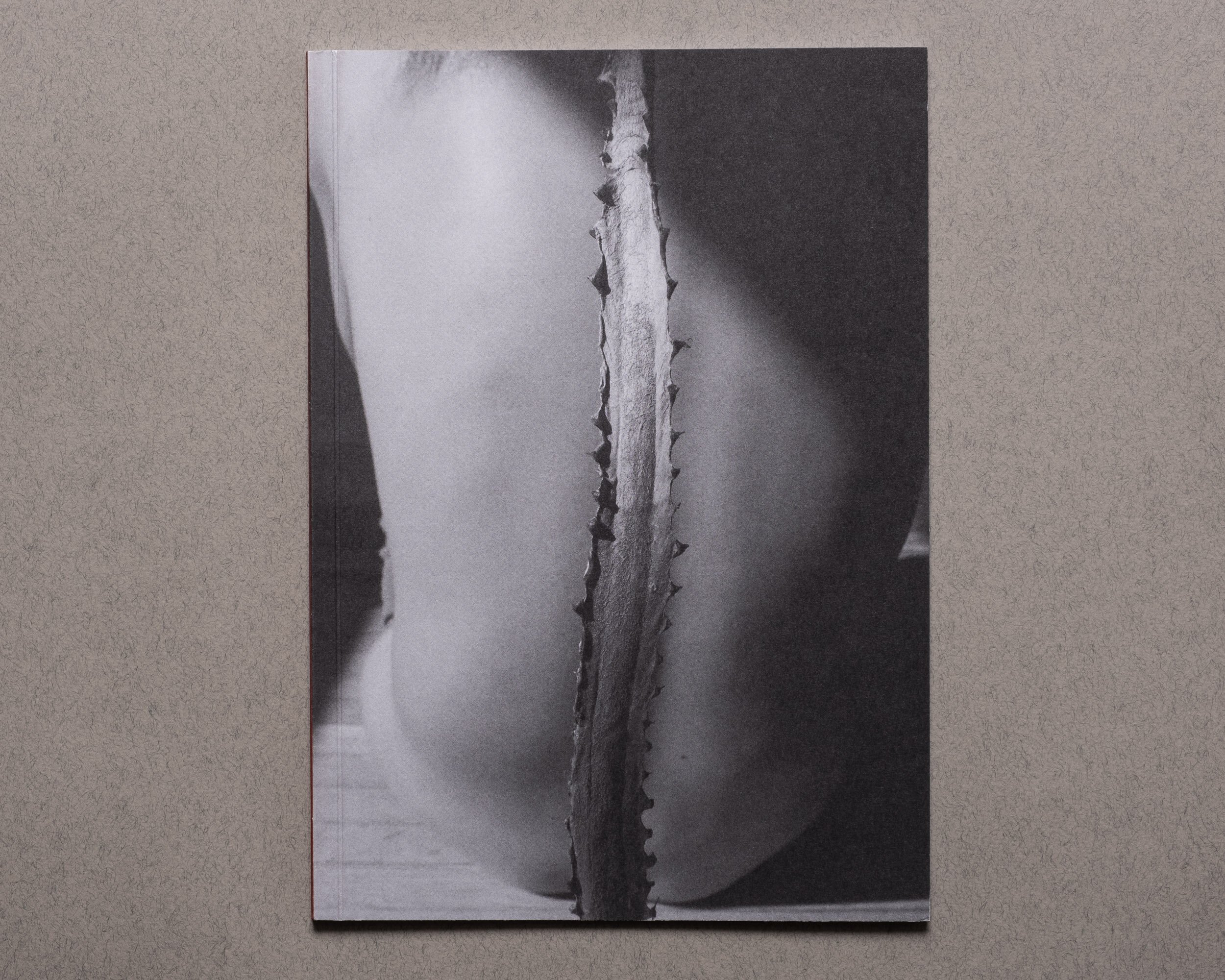

Temple of the Self by Lauren Noelle Oliver. Image courtesy Kris Graves Projects / Monolith Editions.

Much has been written about the place of the feminine nude in the modern era, and it's history as a tool of objectification under the guise of modernist aesthetic. Some long-held modernist “masters” have become known for their photographs of women in the nude, sometimes romantic partners or protégées (or both) years or decades younger than the photographers themselves. While the photographs could vary wildly in their abstractive qualities, a common and accepted comparison was that made between the cisgender female body and the natural world, in a time when both were viewed as consumable and conquerable.

Along with the rise of the countercultural 1960s and second-wave feminism of the 1970s came a number of woman artists who began to subvert the use of the female nude in art through self-portraiture. It is this tradition in which Lauren Noelle Oliver is working, maintaining a relationship to her forebears through her wholehearted investment in analog black-and-white photography. Temple of the Self makes its purpose known immediately through its title; to recognize the human form not only as an analogue for nature and the environment, but as a vessel for one’s consciousness.

The cover image of Temple of the Self is an exquisitely beautiful photograph that immediately calls to mind Edward Weston’s still lives. A long, narrow aloe leaf appears almost metallic, aligned with the spine of a sumptuously lit figure in a sparsely described interior space. While at first the relationship to Weston’s photographs might seem obvious, given the subject matter, there are two distinct differences in Oliver’s photograph; firstly, the plant, though a favored object of study in Weston’s work, is markedly sharper, its spiked leaf echoing the shape of the vertebrae that lie beneath the soft, smooth skin it stands against. Secondly, as becomes clear throughout the book, this photograph is a self-portrait, putting the power of the gaze in the hands of the subject.

The book begins with two photographs examining what we can assume are two different bodies. The first (a self-portrait), uses the subtle tonality coveted by darkroom photographers to abstract a belly, emphasizing the curved shapes of a body as limbs press against the midsection as well as drawing attention to the texture of the skin. The second photograph in the book has a more intense contrast, depicting the divots and hills of a chest against sand that has a comparable landscape. The hair on this chest, compared to the smooth appearance of the previous image, implies a shift in the perceived gender of the subject, as does the crucifix pendant nestled therein. This is the genius of Oliver’s photographs; these gender shifts continue throughout the book, each imploring the viewer to consider what traits and visual cues we gender in one way or another.

As one continues through the book, the images continue to question these notions. Through their position, the two figures that populate the pages of the book are compared in ways that subtly undermine our learned associations of anatomy with gender. While the first two photographic spreads in the book set up a binary, these spreads break it down. When two armpits, both with body hair, are juxtaposed in one image, it forces the viewer to contend with the idea that certain sex characteristics cannot be applied uniformly to one gender. Bodies being pressed together on a bed are abstracted into a landscape, making it unclear where either falls on a spectrum of perceived gender.

Aside from the clever, nuanced visual examination of both figures through this lens, the photographs have a powerful tactile quality that creates a consideration of the body as self, rather than just a vessel for the self. Through the inclusion of various materials and props, Oliver stirs a desire in the viewer to touch and understand the textures she is describing. Her use of light emphasizes the unruly qualities of plants, the itchy beauty of lace against skin, the satisfying feel of a damp braid in one’s hand. The light becomes a character in the photographs, implying the same kind of warmth that results from bodily contact.

Alongside the images lives an essay by Cailey Rizzo, which seems to speak from the perspective of the book itself. There is a lyricism to the words that aligns perfectly with the imagery following it, seeming to live in a world apart while also directly challenging and implicating the viewer. Rizzo writes:

“And the information and images you retain from streets, from conversations, from pages like mine — over time, they become part of you, too. You are a structure whose foundations deepen and walls continually crumble. There is no blue-print to make it all make sense. How could there be? As soon as you’ve located a solid room, the invisible lines of human architecture twist and the building has changed. It’s enough to doom some people. They will forever circle around themselves, blindly hunting for the entrance to the temple of the self.”

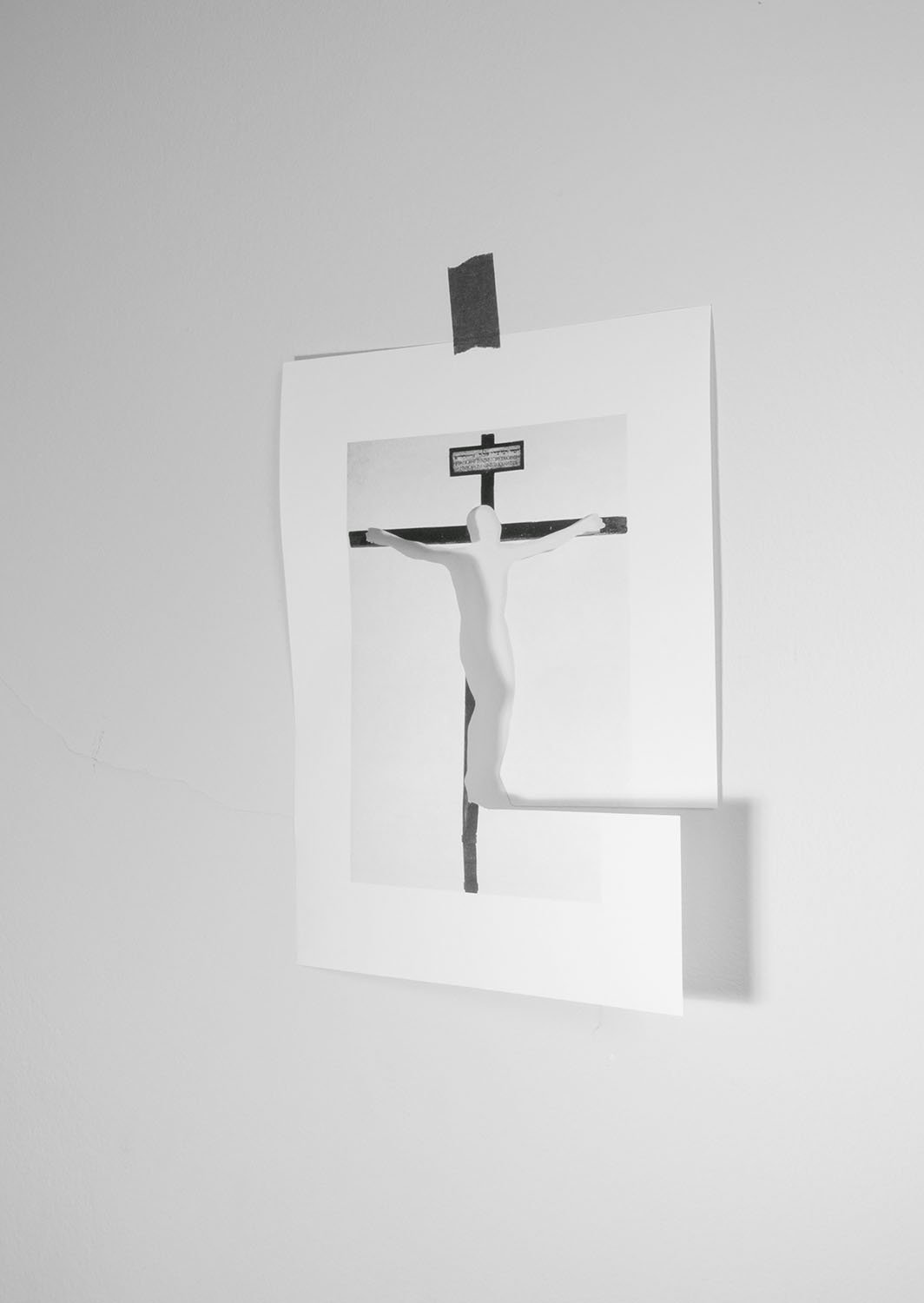

The final two photographs in the book let us inside the temple, too. The penultimate image returns to a crucifix, this time in a drawing taped to a blank wall, looping us back around to where the narrative arc of the book began. This visual recalls a long-held idea within abrahamic religions: that the body is somehow separate from “the soul” or “the self,” that the body is a mortal trapping to eventually be shed. By reminding us of this idea with such a recognizable symbol, Oliver’s work implores us to instead sit with the body as it is now, to understand feeling — physical or emotional — as an important part of selfhood.

A relationship is then formed with the final image in the book, of Oliver’s form on a wooden floor, a warm light catching the contours of her figure. This helps to crack open the notion of a body separate from its self. Boundaries between surface and interior begin to dissolve, and sensation is recognized through these photographs as an important part of existence, rather than a byproduct.

Temple of the Self is available from Monolith Editions.