Book Review: “Good Pictures: a history of popular photography” by kim beil

By InHae Yap | December 15, 2020

Published by Stanford University Press

If finishing a book means reading the text front-to-back, cover-to-cover, then I finished reading Kim Beil’s book, Good Pictures: A History of Popular Photography, almost immediately after I received it in October. I thought that writing a review would be as simple as picking up my pen, looking over my notes, and getting to work as soon as I reached the last chapter. But the leaves fell off the trees, and I am still perusing, flipping through, and poring over this book, months later. Even now, I am reluctant to begin writing, because I still feel that I have not finished reading it.

It’s not as though I have little to say–on the contrary. Good Pictures is centered around an intriguing question, one that is deceptively straightforward, but yields a plethora of rich anecdotes and speculations: what makes a good picture? Or, how and why are certain photographs considered “good” and others not?

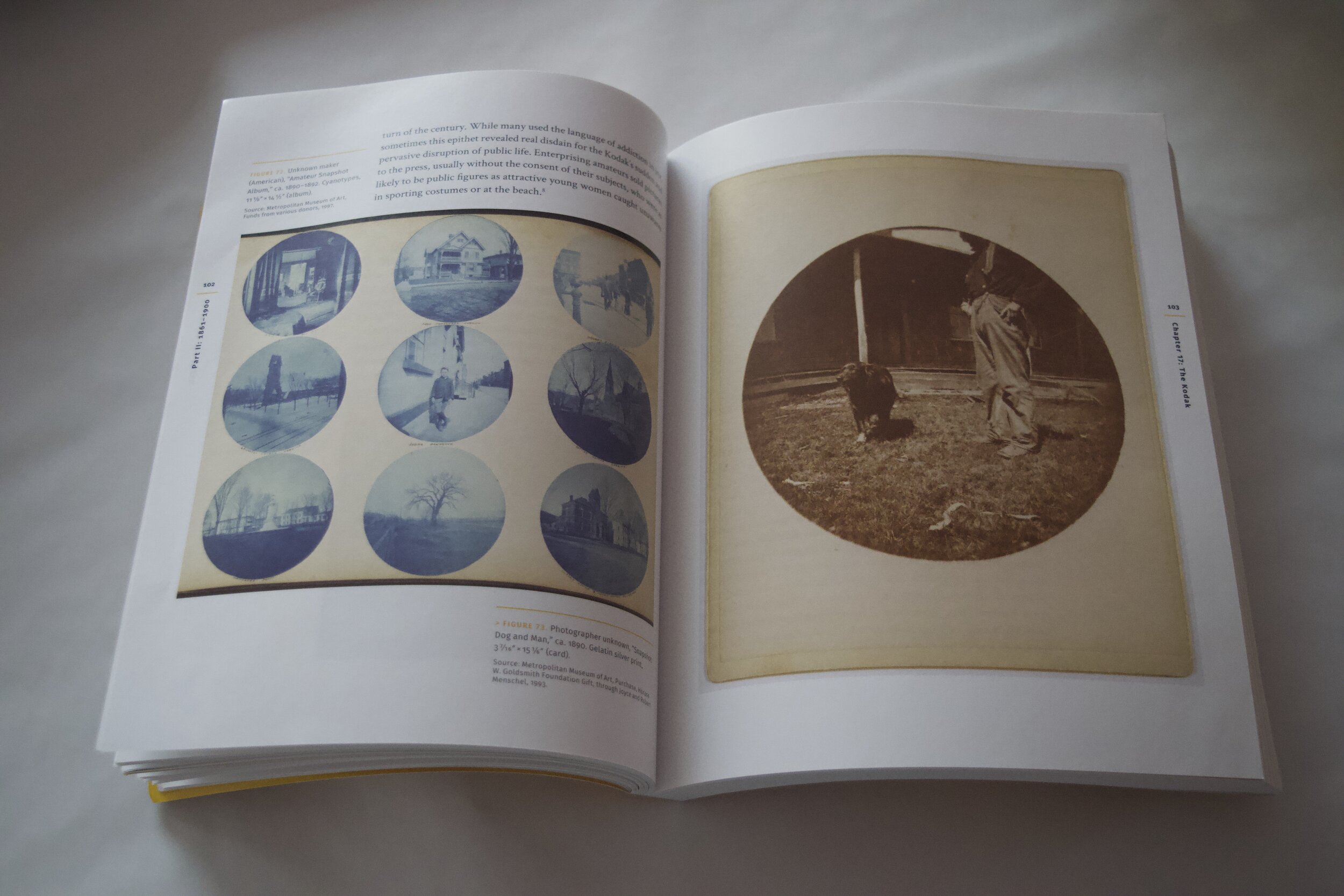

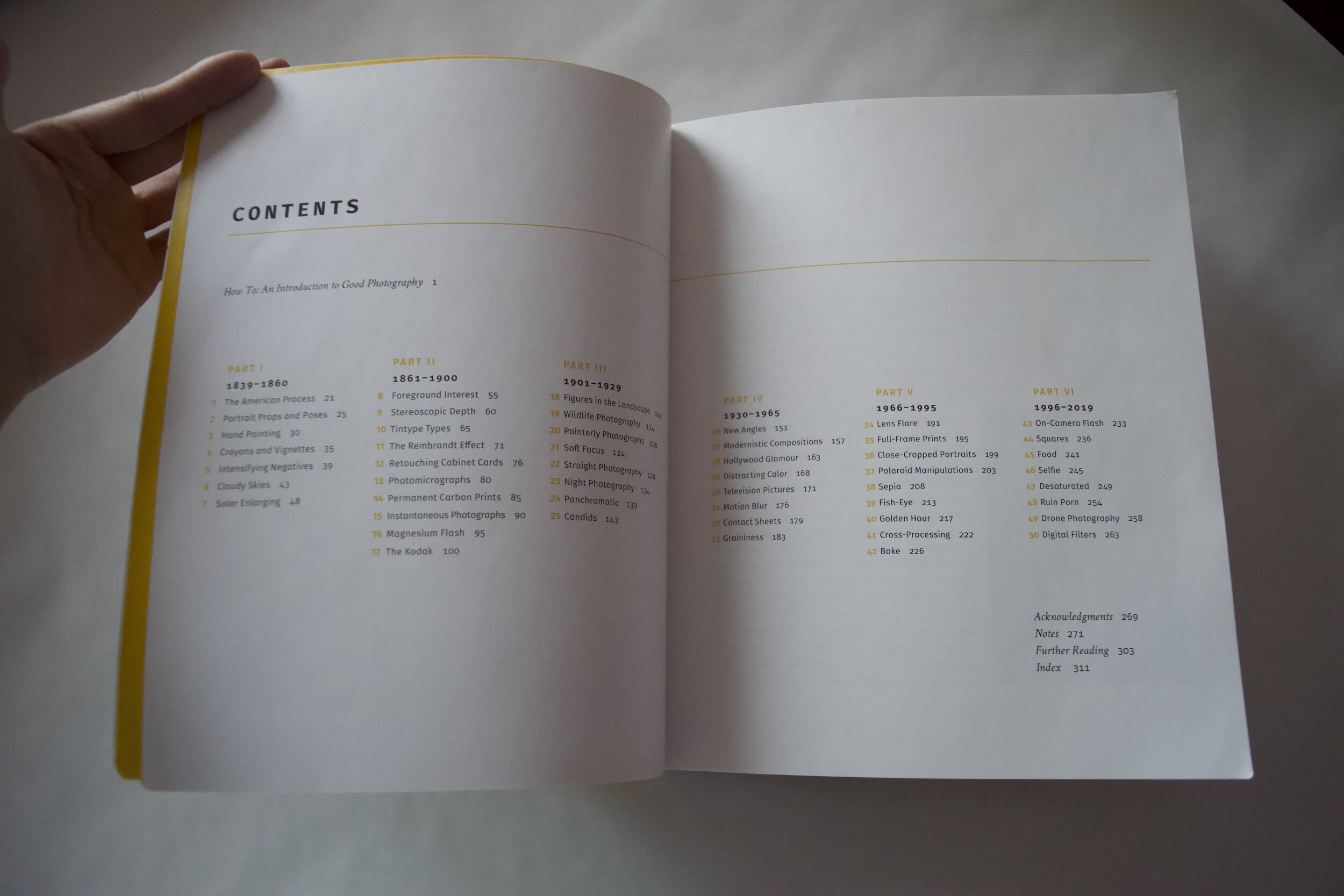

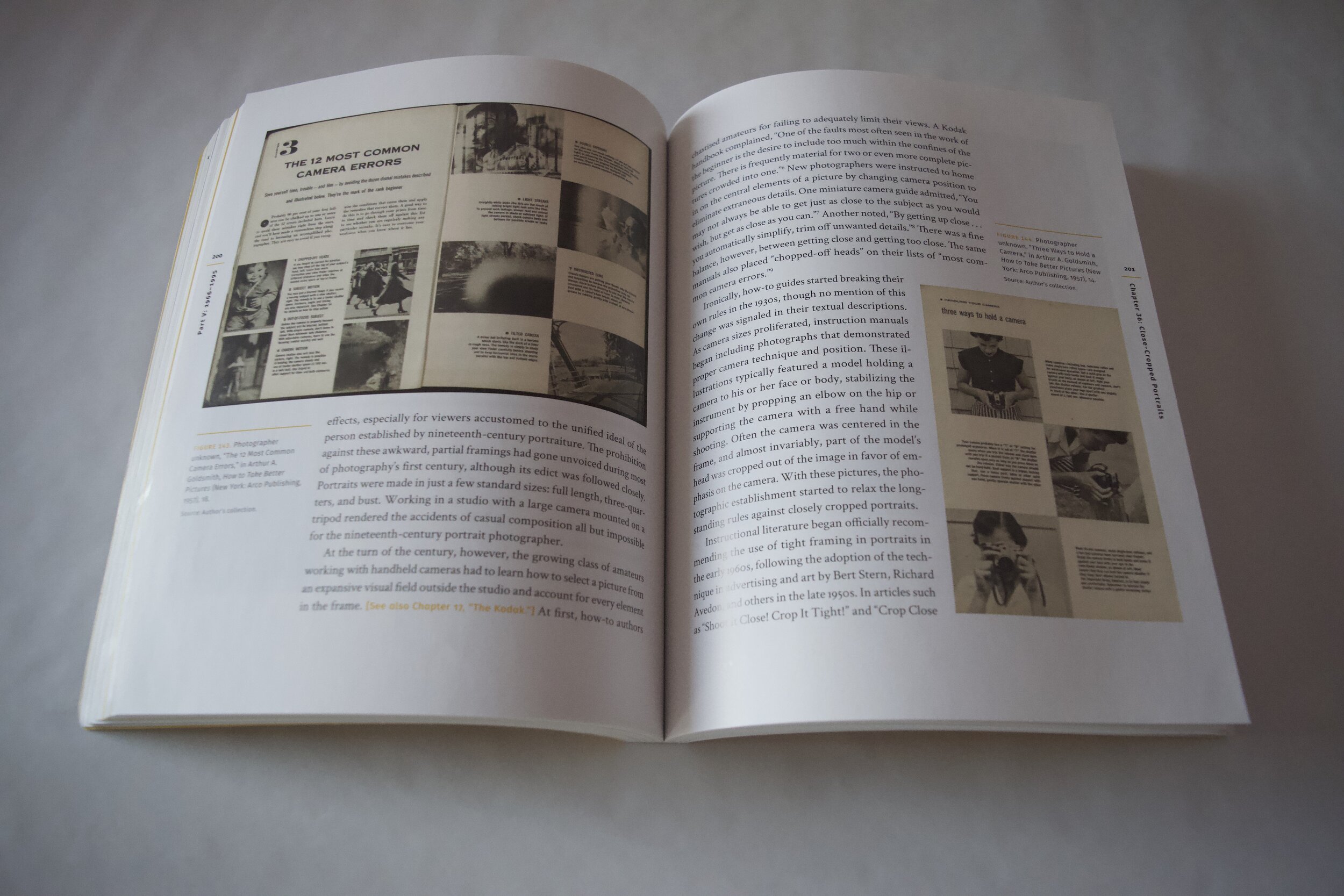

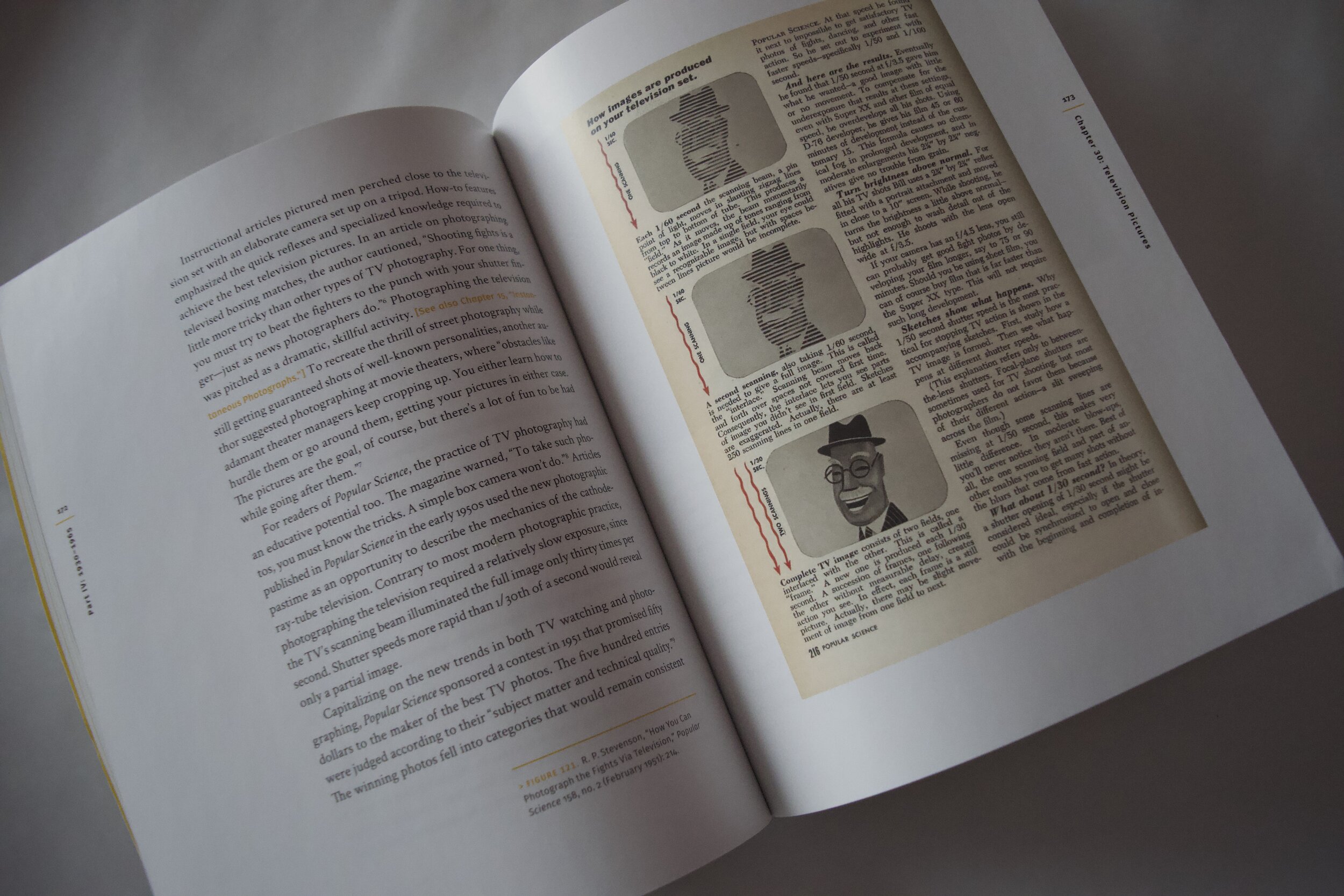

In pursuit of this question, Beil turns to the history of popular photographic trends in the United States, from 1839 to the present day. She follows fifty of these trends, organized into six time periods, which roughly fall under two categories: photographic technology, such as tintypes and fish-eye lenses, and stylistic choices, like desaturated digital photography or the retouching of 19th-century cabinet cards. No image is unworthy of scrutiny, as long as it fits within a trend, so duckface selfies and quotes from Kim Kardashian sit alongside works from Paul Strand and Edward Weston.

Of course, Good Pictures is more than a string of encyclopedic entries, and under Beil’s watchful eye, seemingly outdated and cliched trends are re-enlivened in all their cultural and technological implications. In a clear, lively voice, Beil carries the reader through this dense visual history, even when it covers more specialized topics like carbon prints or collodion printing. As scholarly writings on 19th century photography are often characterized by dry, overly-technical assessment of the science and chemistry behind these processes, this alone is an impressive feat; I have vivid memories of my eyes glazing over whenever assigned such texts in my art history classes.

This, thankfully, is not the case with Good Pictures, although Beil is no slouch when it comes to the scientific explanations behind photographic technology. A chapter on 19th-century combination printing, for instance, is organized around the struggle to depict cloudy skies in photography: “The subjects of early photographs,” it begins, “lived all their days under cloudless skies.” This observation, clearly seen in accompanying illustrations of blank skies above detailed landscapes, is easy to follow and sets the tone for the rest of the chapter. Technical aspects of the process are mentioned only insofar as they relate to clouds: what made capturing clouds so difficult with early cameras, how photographers overcame the issue by merging multiple negatives, and why “picking clouds out of a box,” as Beil eloquently puts it, was in equal parts scorned for its inauthenticity and admired for its enhancement of atmospheric effect.

Whenever possible, Beil seeks out racial and gendered aspects of what makes a good picture, in surprising ways that surpass the usual questions of photographic representation. A particularly striking example is the chapter on golden hour photography, which begins with the following remark: “For most of the twentieth century, there was no golden hour.” Early manuals on color photography often instructed readers to avoid the sunset and sunrise hours, but by the 1980s, the undesirable “sun-burned effect” in photographic portraiture had been rebranded as a healthy “golden glow.” Beil is quick to discern the racial implications at play in this transformation, noting that critics’ use of ‘golden hour,’ as either a pejorative or complimentary term, had pale white skin in mind–as did the companies producing color film in the first place. “Acceptance of golden hour lighting,” she writes, “required much more than simply learning how to anticipate the objective rendering of warm light on film … white photographers, critics, and subjects had to expand their understanding of the variable nature of skin tones as represented by color film.”

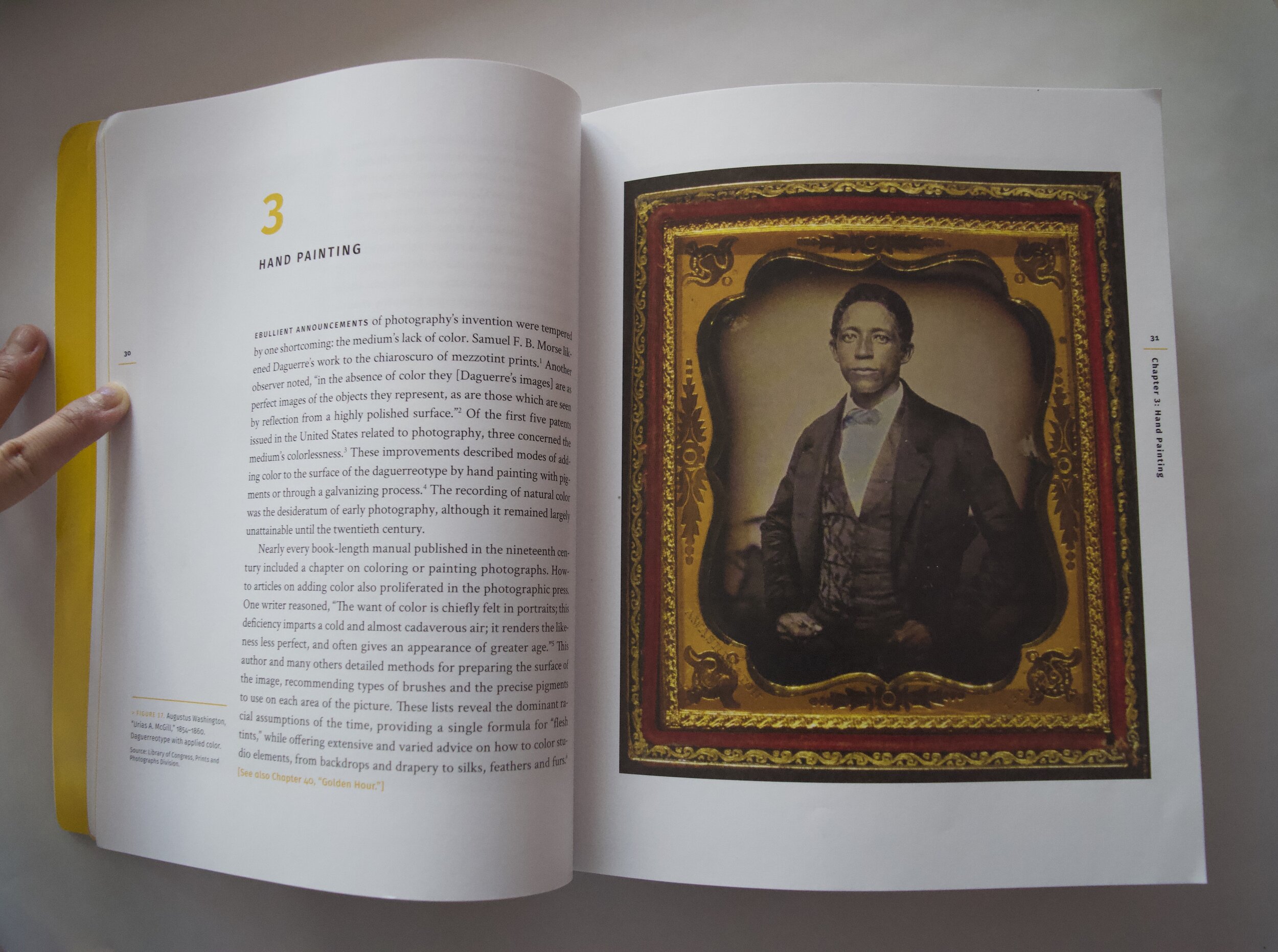

I’m not sure if the weight of this claim is fully realized, since the chapter–and the book at large–is populated largely by those white photographers, critics, and subjects of whom Beil speaks. In fairness, “American popular photography” is a vast genre, and Good Pictures doesn’t claim to provide a comprehensive history. It is worth noting, however, that there are only two people of color to be found in the entire repertoire of images: one of the African-American daguerreotypist Augustus Washington, and a tintype of an anonymous boy from the Civil War era. This is largely due to the fact that Beil’s analysis relies primarily on how-to photography manuals, advertisements, and mainstream print culture, none of which were inclined to include people of color until much more recently. Still, Good Pictures speaks to the fact that we must attend to that which is not seen in photography’s vast archive, even within seemingly mundane trends like golden hour photography.

“Hand Painting” chapter from Good Pictures. Daguerreotype of Augustus Washington, with applied color and frame.

Good Pictures moves at a rapid pace, devoting no more than four or five pages to each chapter. This brevity allows Beil to cover a far wider terrain than most scholarly work, and Good Pictures proves that prioritizing breadth can yield equally rich insights to a lengthy analysis of a single, niche topic. That’s not to say that it isn’t well-researched–far from it. Each chapter is replete with endnotes, references, and plenty of images, all painstakingly sourced from a wide variety of archives. But as we flip through the 19th century and into the 21st, it becomes increasingly obvious that the logic behind a “good picture” is nowhere near as linear as the book’s chronological layout might suggest.

Take, for example, pictorialism, one of the earliest attempts to aestheticize what had hitherto largely been considered a science. Pictorialist photography sought to emulate paintings and drawings, then the standard for what could be considered ‘art.’ Warm water brushed onto a gum bichromate print, for instance, allowed photographers to overlay photographs with watercolor-like washes. By the early 20th century, pictorialism was rejected in favor of ‘straight’ photography, characterized by its sharp focus, minimal retouching, and microscopic detail. But it’s impossible to kill an idea, and Beil makes this eminently clear much later in Good Pictures, when the ghost of pictorialism emerges from romantic, deliberately smudgy Polaroid prints in the 1980s.

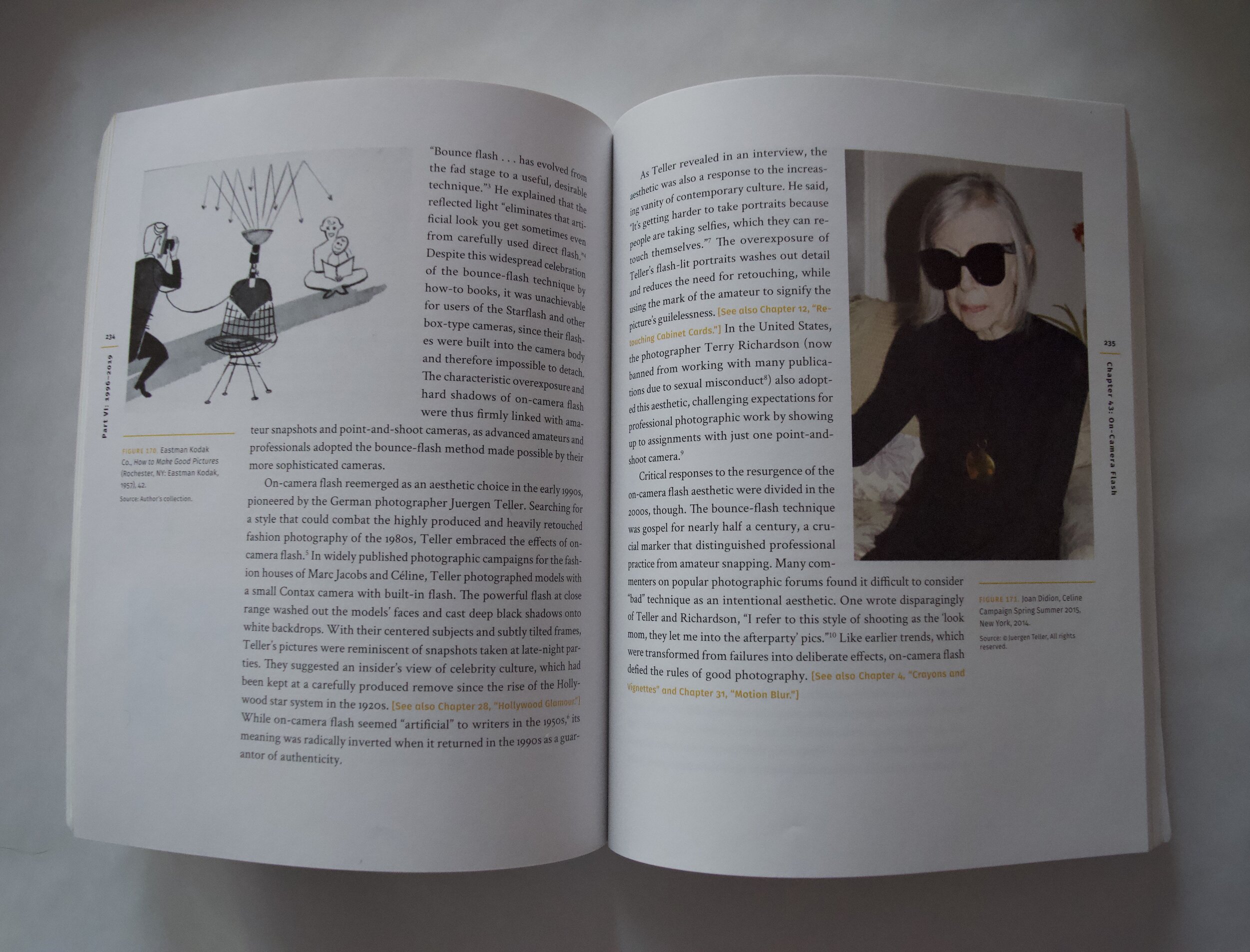

This revival of old trends becomes a familiar pattern as the book progresses. Sepia coloring escapes the 19th century and weaves in and out of the 20th century, coinciding with times of economic prosperity, while #nofilter Instagram photos find surprising resonance with the old straight/pictorialist debate. And lest you make the mistake of thinking any trend is truly ever ‘dead,’ Beil helpfully cross-references the chapters, encouraging readers to double back and find these connections for themselves. The section on “Digital Filters” alone directs readers back to four other chapters, including “Permanent Carbon Prints” and “On-Camera Flash,” leading to a dizzying mish-mash of styles, media, and time periods. Careful editorial choices regarding image layout also support the text in keeping up with this chronologically bewildering mix of decades and trends. The drastic transformation of flash use in photography, for instance, is almost better explained by two images standing across a two-page spread than the text itself: on the left, a illustrated instruction from 1957 for using bounce-flash, intended to create soft lighting; on the right, a 2014 photograph by Juergen Teller of Joan Didion, whose soft wrinkles and gray hairs stand out sharply against a harsh camera flash. Reading Good Pictures is much more akin to reading a magazine than to a book, where readers flip back and forth between chapters and images, illuminating surprising visual connections across vast timescales and different media.

“On-Camera Flash” chapter in Good Pictures. Left, bounce-flash illustration from the 1957 edition of How to Make Good Pictures, Eastman Kodak Co. Right, Joan Didion, photographs by Juergen Teller for Celine Campaign Spring Summer 2015.

By the end, we are left with the distinct suspicion that the criteria for ‘good pictures’ is, ultimately, rather arbitrary. It’s not as if Beil doesn’t warn us from the start: “‘How to make good pictures,’” she writes in the introduction, “is actually a question, one that has no fixed answer.” Tellingly, there is no conclusion to the book. Still, even if it is impossible to make the ultimate ‘good picture,’ one that will be considered as such long into the future, make no mistake–‘arbitrary’ is not the same thing as ‘meaningless.’

One example immediately comes to mind, as 2020 winds down. The publication of Good Pictures this summer coincided with wider global conversations about police brutality and violence, which, due to COVID-19, took place largely on social media. Many of us, myself included, were grappling with the politics and social dynamics involved in posting related images to Instagram. (Who’s posting pictures of the protests? Who’s suddenly talking about Black Lives Matter? Who’s still talking about Breonna Taylor? Who’s posturing, and who’s genuine? When can we all go back to posting food and selfies?) If this seems a ridiculously trivial issue in light of larger structural violence and policing issues, then that is precisely the point, because we were wrapped up in these conversations anyway despite acknowledging that absurdity.

In the long run, does it really matter what you did or didn’t post to Instagram in 2020? Probably not. Still, these choices are revealing of how we choose to assert political allegiances and identity, and how photographs are mobilized towards these ends. As Beil aptly demonstrates, there is a lot at stake in a good picture, even if she leaves readers to determine those stakes for themselves. This open-endedness is what makes Good Pictures particularly instructive, and endlessly generative. Whether I approach it as a researcher, Instagram junkie, or photographer, Good Pictures is certainly one of those books that I will keep within easy reach on my bookshelf.

(I haven’t finished reading.)