Book Review: “SCUMB Manifesto” by Justine Kurland

By Keavy Handley-Byrne | December 15, 2022

Published by Mack in May 2022

Essays by Marina Chao, Renee Gladman, Justine Kurland, Catherine Lord, and Ariana Reines

Softcover / 11.6x9.25 inches

SCUMB Manifesto, Justine Kurland. Images courtesy Mack Books.

In her 1967 self-published pamphlet, SCUM Manifesto, Valerie Solanas writes: “A ‘male artist’ is a contradiction in terms. Having nothing inside him he has nothing to say.”

Solanas’ Manifesto is a polemic, and Justine Kurland’s SCUMB Manifesto – where Solanas advocated Cutting Up Men, Kurland instead suggests Cutting Up Men’s Books – follows suit. Drawing from her extensive personal library of photobooks, Kurland has been dissecting images by men for several years now, a departure in terms of her visual language, which has been thoroughly photographic up to this point.

Unsurprisingly, Kurland’s volume contains a number of collages partially or entirely assembled from photographs of nude women, a subject tirelessly recycled in the world of male photographers. She subverts this dehumanizing visual history through composing vulvar and vaginal shapes from the further dismembered bodies of these subjects, revealing the (questionably) subconscious objectification that so many male photographers impose upon their models and muses. The violence of this gesture is emphasized by placing disembodied nipples and legs in tangled and twisting positions, removing eyes that would challenge the imposing male photographic gaze.

The concept of the female “muse” in art, regardless of the medium, is one that has been romanticized (and eroticized) for centuries. Kurland’s work is the latest in a line of feminist artists that challenge the acceptance of this dynamic. Particularly salient is Eleanor, a montage of its namesake, Eleanor Callahan, whose fragmented body tessellates across the page, glued back onto the gutted inside covers of the book itself. Many of Kurland’s collages are made on the endpapers of the very books their building blocks come from, the bedraggled threads of their bindings adding visual complexity to each assemblage (the spine of Kurland’s book, for its part, is perfect-bound, imitating the appearance of the books she has used as fodder). Some elements of her photo-montages fit neatly together, as if laser-cut, while others show a distinct hand, with jagged edges from dulling Exact-o blades, feverish rage, or perhaps both.

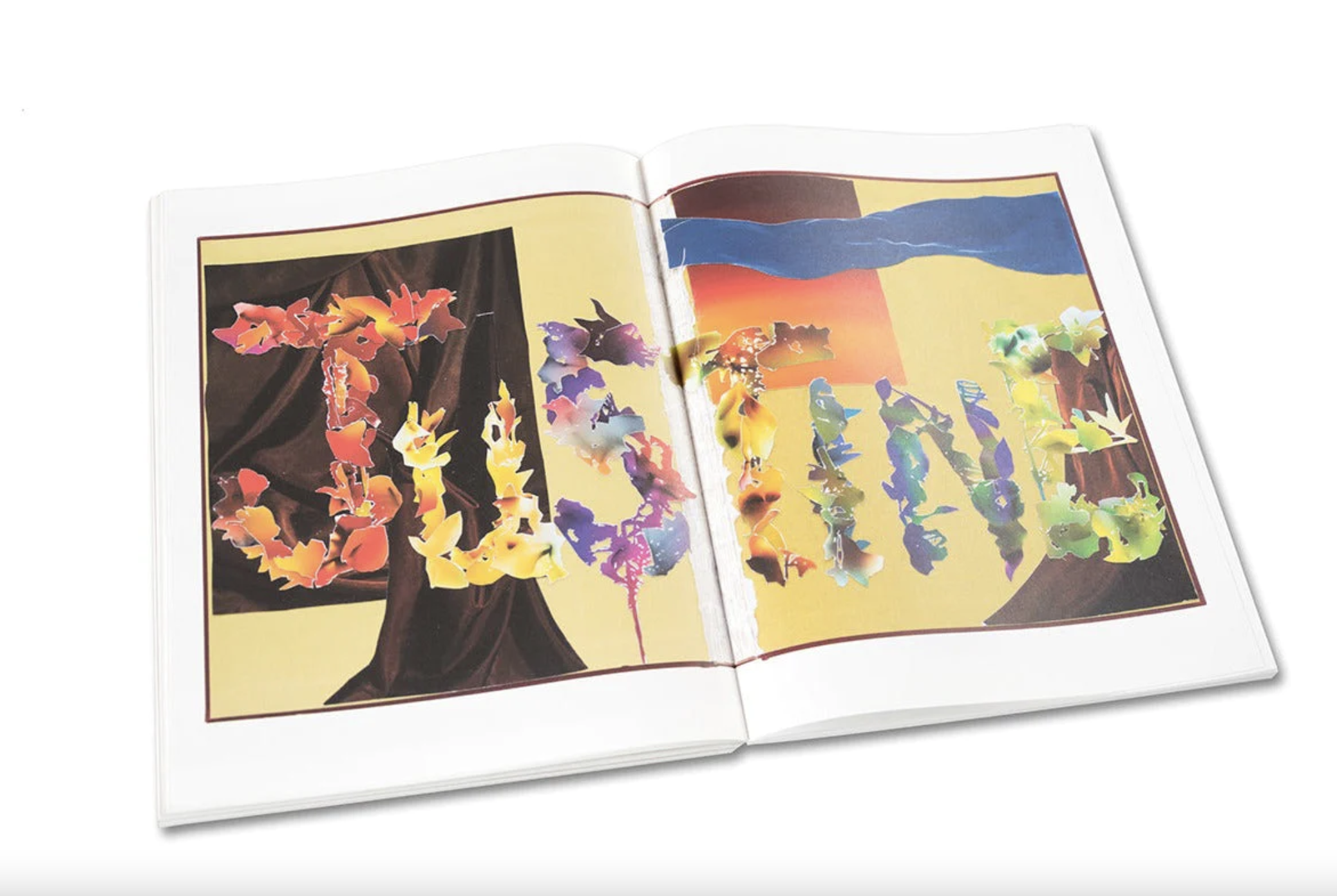

An early spread in the book, titled Cottonwoods (Justine), cuts from Robert Adams’ photobook Cottonwoods and reassembles the branches, with surgical precision, into Kurland’s first name. She assembles her own name more than once from the entrails of mens’ photographs, as well as the names Valerie, for, of course, Solanas, and Lorena, for Lorena Gallo, formerly Bobbitt, who became famous in 1993 for cutting off her husband’s penis after suffering horrific physical, sexual, and emotional abuse at his hands.

Another work in the book bears Gallo’s married name (which she no longer uses) in its title: Untitled (Pompidou, After Lorena Bobbitt). The collage is a reconfiguration of photographs by Hans Bellmer, a surrealist known for his photographs of self-made dolls modeled on a pubescent cisgender female body and outfitted with extra breasts and genitalia. Bellmer’s photographs literally objectify and fetishize the female body, occasionally picturing his dolls with no heads, and almost always in the nude. Kurland takes elements of these photographs and constructs a penis and scrotum, turning Bellmer’s objectification back on itself, disembodying the genitals as a gesture of her desire to impose discomfort on male photographers who openly fetishize the female form.

This collage is complicated not only through this title, which takes a jocular tone, but through the figuration of a phallus. The title is admittedly clever, given the visual references to Frankenstein’s Monster, and John Wayne Bobbitt’s participation in a pornographic film called Frankenpenis following the surgical reattachment of his penis. The inclusion of both Gallo and Solanas’ first names does draw a comparison between each of them, too; abusers of any stripe use mistreatment of their victims to exert control. Solanas confessed after turning herself in to the police for shooting Andy Warhol, saying: “He had too much control over my life.”

Despite the shrewd quip and the smart comparison, there is something about the references to the Bobbitt case that feels unsettling. The incident has been the subject of public humor, mostly at Gallo’s expense, for nearly thirty years, despite the brutal abuse that Gallo suffered in advance of the assault. Invoking Gallo’s married name in this context, while making work intended to undermine male domination and violence, leaves a bit of a bad taste in the mouth. Is it necessary to use her painful history as a survivor of abuse as a punchline?

Additionally, there is the issue of Solanas’ Manifesto, associated with second-wave feminism, and its negative effect on the radical feminist movement. Though in some ways the text is deeply relatable in its longing for a reversal of male supremacy, Solanas is considered by many queer and feminist scholars alike to conflate maleness with genitalia, and further, the penis with inherent violence.

This assertion is one that Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminists (TERFs) continue to make, outright declaring, as Solanas does, that those assigned male at birth who later identify as women are not “real women.” Bio-essentialist views posit that one’s gender is determined strictly by one’s assigned sex at birth. When extended, this line of thinking can be used to paint trans people as predators, which is an idea that continues to cause harm to the trans community (particularly transgender women of color) to this day.

Kurland, for her part, may not intend to encourage this association. She has been careful to avoid using the books of queer-identified, black, and indigenous male artists in SCUMB Manifesto, indicating an intersectional understanding of power dynamics that often privilege a white woman’s experience and advancement over that of a man of color. SCUMB takes aim at a canon of photography that is still taught in formal photographic education settings, and which is overwhelmingly white, straight, and male. Even the cover text calls out higher education’s complicity in this narrow vision of what photography can be: “I see you there in your fat tenure chair, ogling freshmen girls with a rapey smile. I’m coming for you with a blade.”

It is hard not to feel invigorated by this open threat; Kurland speaks for so many young photographers who have watched a white, straight male colleague advance for no other reason than looking and acting like those who wield institutional power. She speaks for those who have been betrayed by their professors and program directors meant to guide and develop student work, who instead use their positions to enact predatory violence.

The thorniness and complexity of SCUMB Manifesto is perhaps precisely the point (pardon the pun). Just as there is no simple solution to social inequity, there is no simple truth to take from Kurland’s collage work, as truth itself resists simplicity. Perhaps instead, SCUMB Manifesto is a body of work that makes room for the dark impulses that so many women feel in response to patriarchal domination.