Book Review: “Paul’s book” by collier schorr

By Jess T. Dugan | January 30, 2020

Published by MACK in October 2019

Quarter-bound hardback / 9.5" x 12" / 144 pages

The relationship between a photographer and their subject is a complicated one. Because making a portrait requires an intimate interaction between two people, the resulting image is infused with their subjectivities, and more importantly, the chemistry between them at that particular moment. It is – or at least it can be – a multifaceted dance of desire, full of projections and longings and connections and unexpected moments.

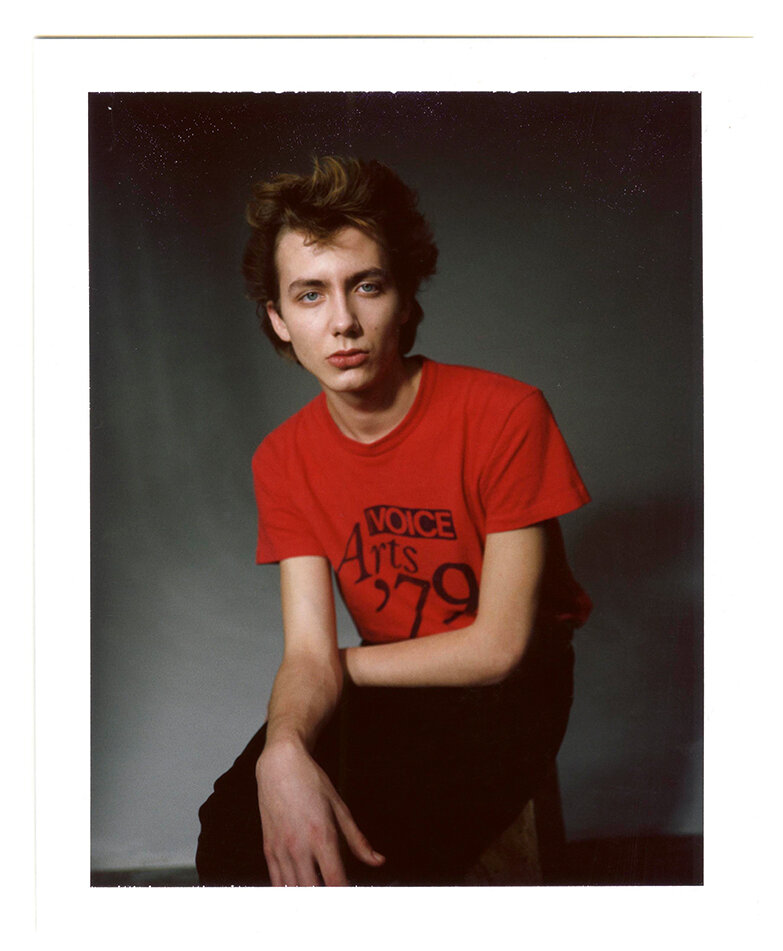

Collier Schorr’s newest publication, Paul’s Book, takes this very topic as its subject matter, focusing on Schorr’s relationship with one of her subjects, Paul Hameline. Schorr met Paul, a young French artist and model, in New York in 2015 and invited him to her studio for a “go-see,” a test shoot to see how a subject looks in front of the camera. The chemistry clicked, and Schorr photographed Paul over a period of two years. Of the book, MACK, the publisher, writes, “the idea was for Paul and Collier to experience photography as a social space, a conversation in which his body and her eyes could try and understand each other’s fascinations and fantasies.”

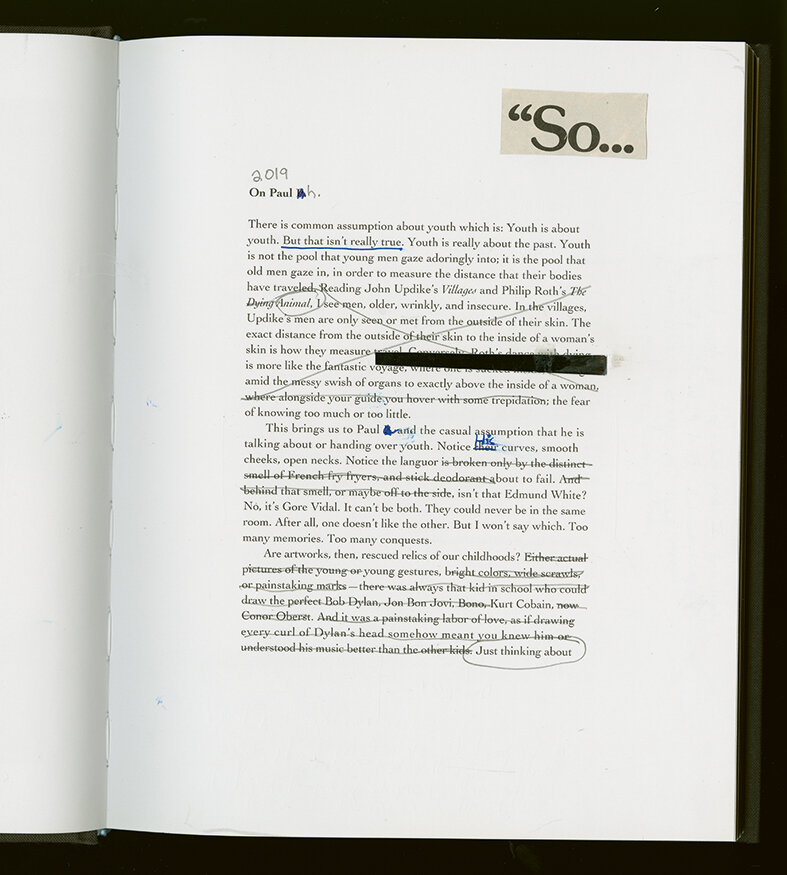

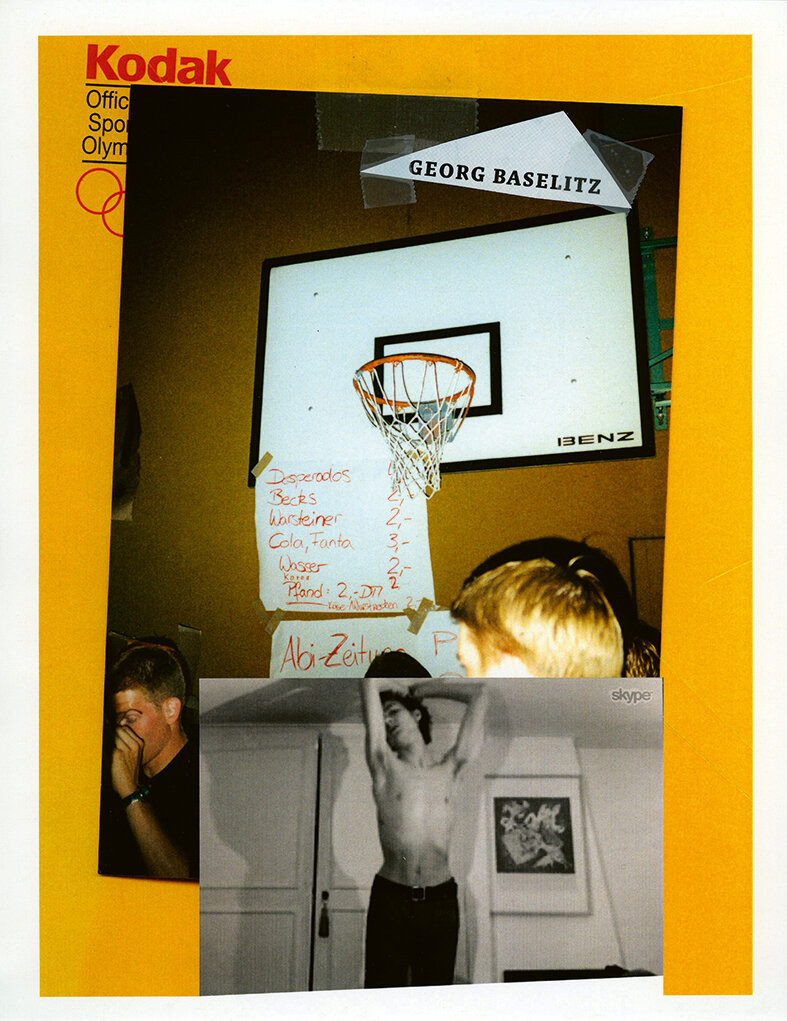

Collage, and appropriation, are used heavily throughout the book. On the first few pages, we see a reproduction of an essay Schorr originally wrote for Paul P’s book Nonchaloir, which she reinterpreted to talk about Paul H. The first lines read:

There is common assumption about youth which is: Youth is about youth. But that isn’t really true. Youth is really about the past. Youth is not the pool that young men gaze adoringly into; it is the pool that old men gaze in, in order to measure the distances that their bodies have traveled.

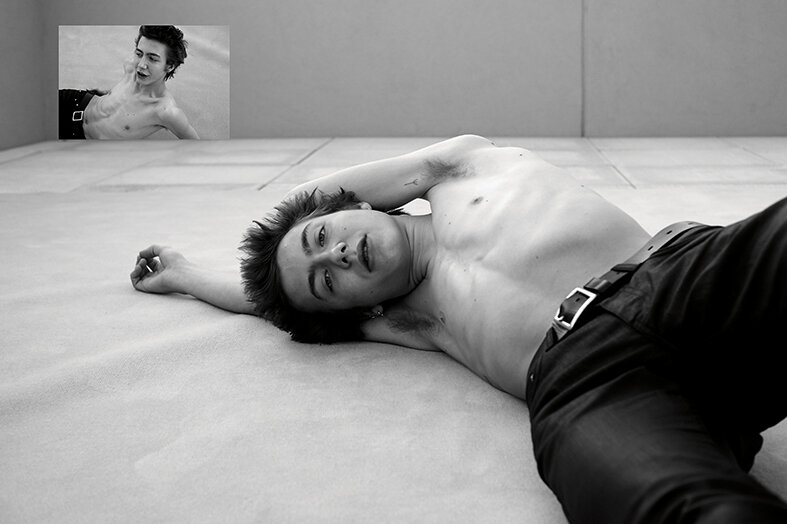

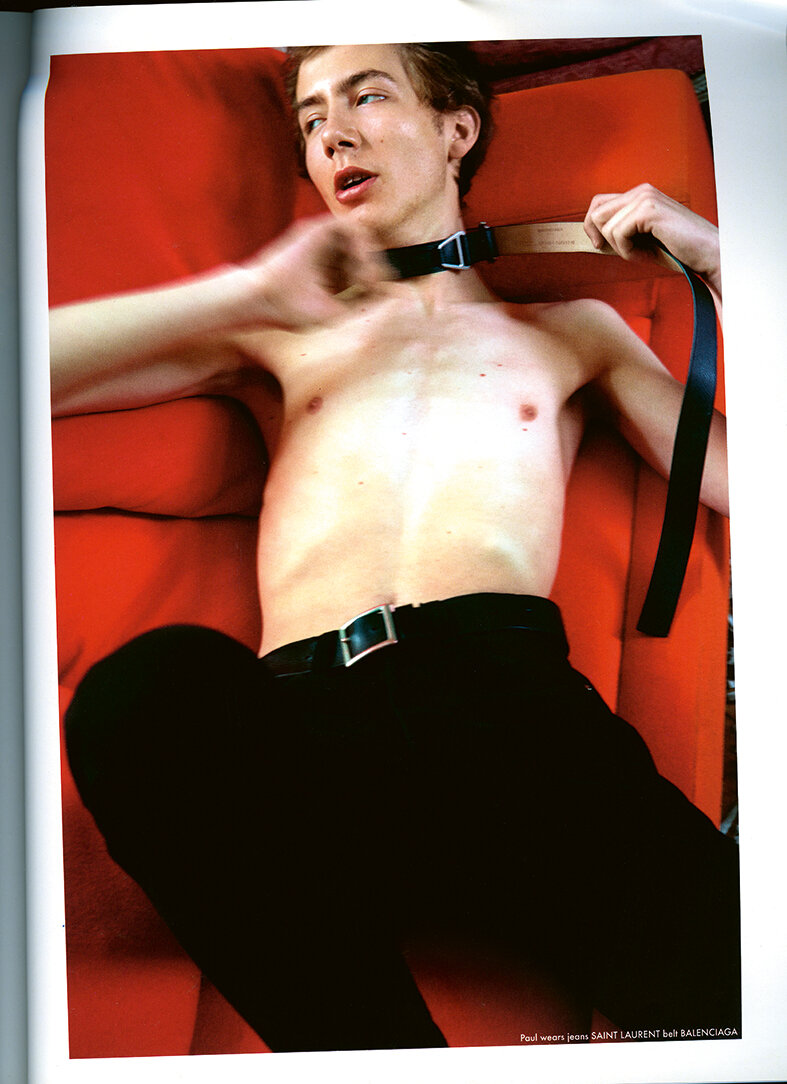

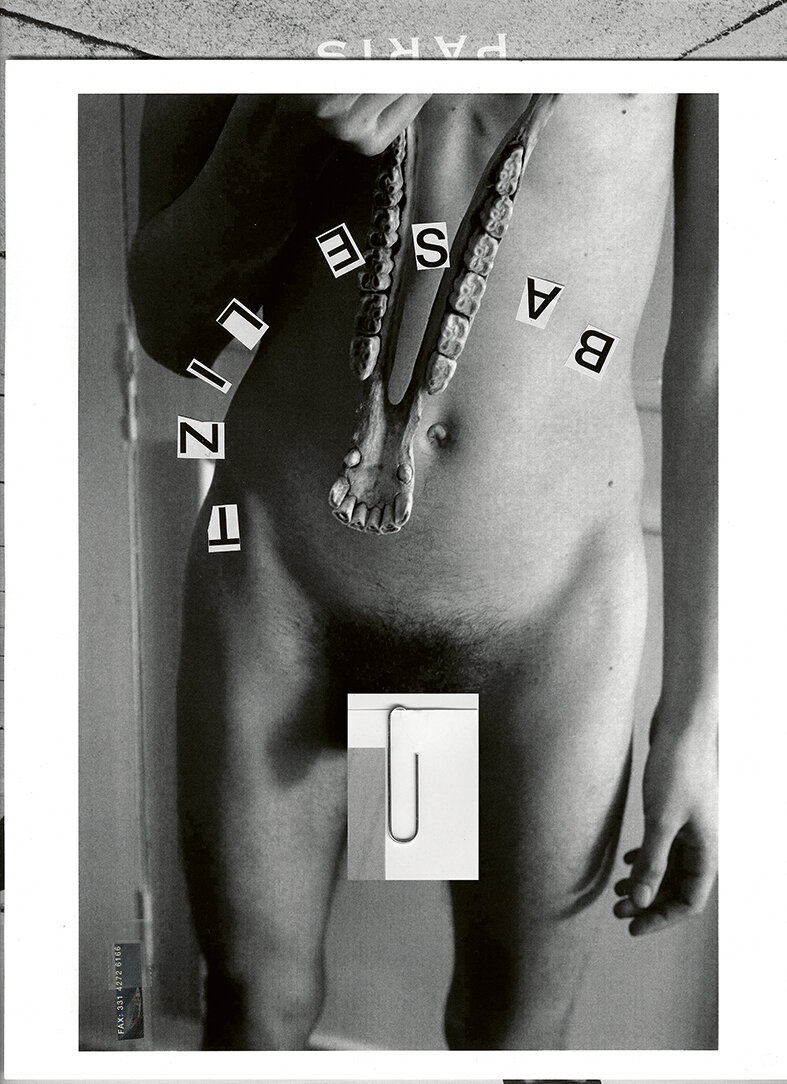

In Schorr’s signature style, this piece of writing is reworked, with sections crossed out, notes written in the margins, and images overlaid, including a photograph from Schorr’s earlier project, Jens F, beneath handwritten text reading “Jens was here first.” Schorr is remixing herself, blending past and present, fact and fiction, self and other. The following photographs of Paul hit a range of emotional notes; in some, he looks especially young and earnest, while others have a heavier weight and maturity. Some are stylized, the influence of fashion visibly present, while others are more raw. Paul appears in various states of undress; in some images, portions of his body are obscured by layers of text or other images, overlaid by Schorr, further complicating the desire to both look and to be seen and the ability/inability to do so.

One of the most captivating aspects of the book, for me, is how Schorr’s presence can be felt in the images of Paul, although the inclusion of her physical self is used sparingly. She does appear, literally, in some images – laying on her back on a rooftop with her camera turned upwards at Paul, pointing her camera at Paul through the small square rectangle of a video chat, reflected in a framed photograph. I appreciate the way she looks unabashedly, making photographs embedded with sexuality, and find myself wondering about the extent to which these photographs are a reflection of her own desires.

A series of questions, written by James Crewe as an essay, appears throughout the book. These questions move fluidly between photographer and subject, some being asked of Schorr and others being asked of Paul, but this distinction is not explicit. For example, one page reads:

Is there a picture that you would like to create with Collier – or any photographer for that matter?

How does it feel to work with him?

How does it feel to work with her?

How does it feel to work with them?

Your lips look soft… your hair looks bouncy… your skin looks clean shaven… is there a secret or a process to your beauty?

Do you ever feel unresolved? Collier strikes me as always searching for an answer – to capture a definite image of the subject – has she resolved you? Is this book a resolution?

Do you admire anybody?

What was the last significant thing you discovered about your personality?

Formally, Schorr moves between color and black and white, high resolution photographs and pixelated screenshots, all the while interspersing layers of text and collage. The book is infused with a sense of play, and discovery, that feels both poignant and refreshing. Rather than striving to make a body of work about something through the inclusion of narrative pictures, Schorr took as her subject matter the process of looking, of connecting, of knowing, of dancing visually and emotionally with another person. There’s an earnestness in this undertaking, a trust in both the artistic process and the ability to make a meaningful connection with others through the act of photographing and the practice of sharing time.

The book concludes with writing by Schorr, broken down into several sections: “Notes on Tricks,” “What versions exist here?”, “The Runaway,” and “You cover the waterfront.” In this concluding text, Schorr grapples with questions of identity, relationships, agency, and desire that are at the heart of Paul’s Book, writing:

This brings us to Paul and the casual assumption that he is talking about or holding (handing over) youth. Is he? Notice his curves, smooth cheeks, open neck. Do you assume he is connected to me, is his gaze connected to me, to be seen by me, or is his gaze past me, with a connection to a page, a printed page of his mirror reflection? Paul is playing a picture, in each picture. Because he is so aware of pictures and their effect on viewers and we are talking as we make these pictures.

I am a lesbian and I am between 52-54. He is a man between 19-21. The partnering we do, like in dance, suggests difference but not always power. I’m being ambiguous here because it’s enough to say who I think I am at this exact moment. Can I say who anyone else is? He is not performing gayness for me, it is not a matter of gay for pay like the boys from Paul P’s book. Factually, emotionally, the performances or the lack of our lack of performance differs on different days. I have often asserted that when I photograph boys, and men, that I am occupying a heterosexual gaze. I’m not sure I believe that anymore. I said it in response to the way in which the gay male gaze seems to be ascribed to me. But truthfully it is not a gaze of asexual orientation. It is a camera and it’s pointed in someone’s direction and I am looking through it. It’s an object with a hole through which I can look without having to be sexual.

Paul’s Book is available from MACK.

All images by Collier Schorr and courtesy the artist and MACK.