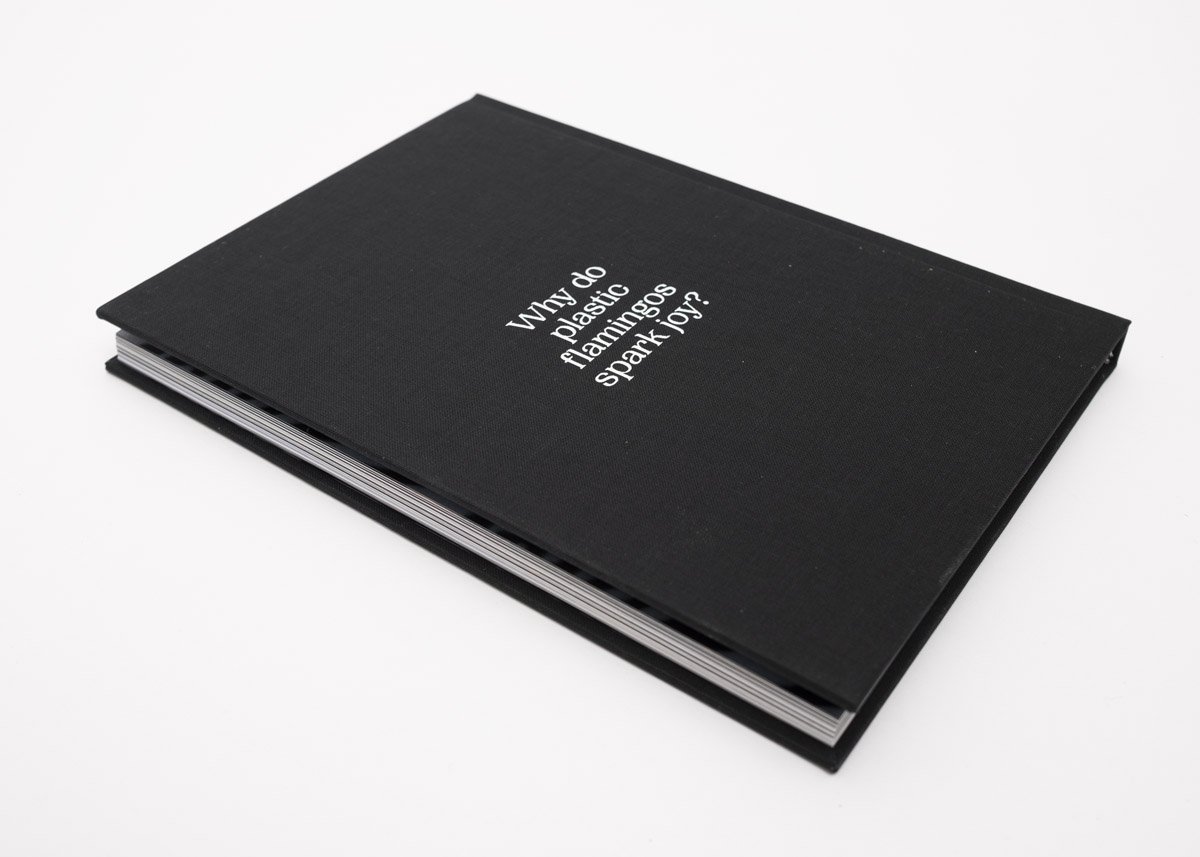

Book Review: “Biophilia” by Annegien van Doorn

By Delaney Hoffman | June 2, 2022

Self-published in 2022

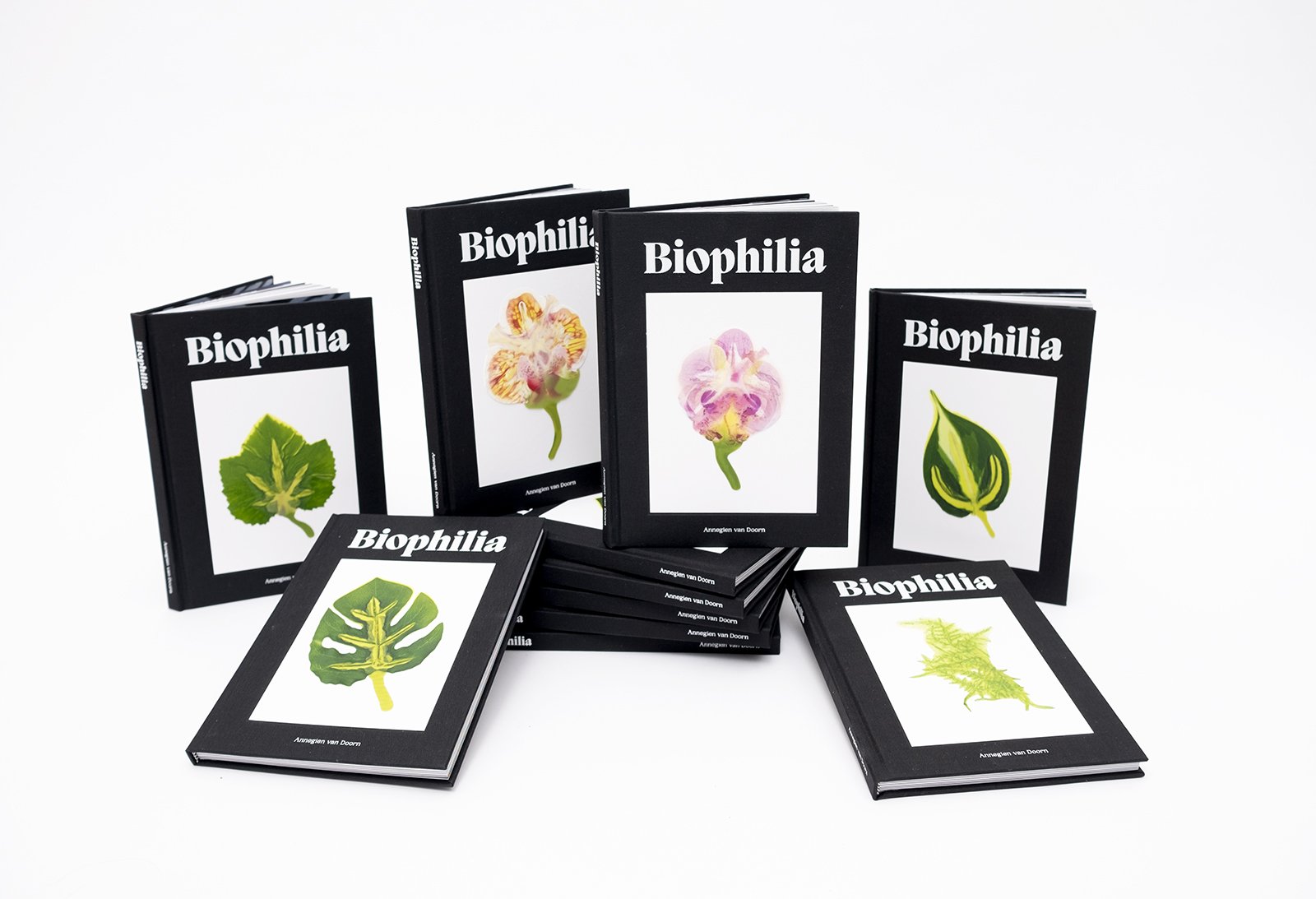

Hardcover / 16.5 x 23 cm / 116 pages

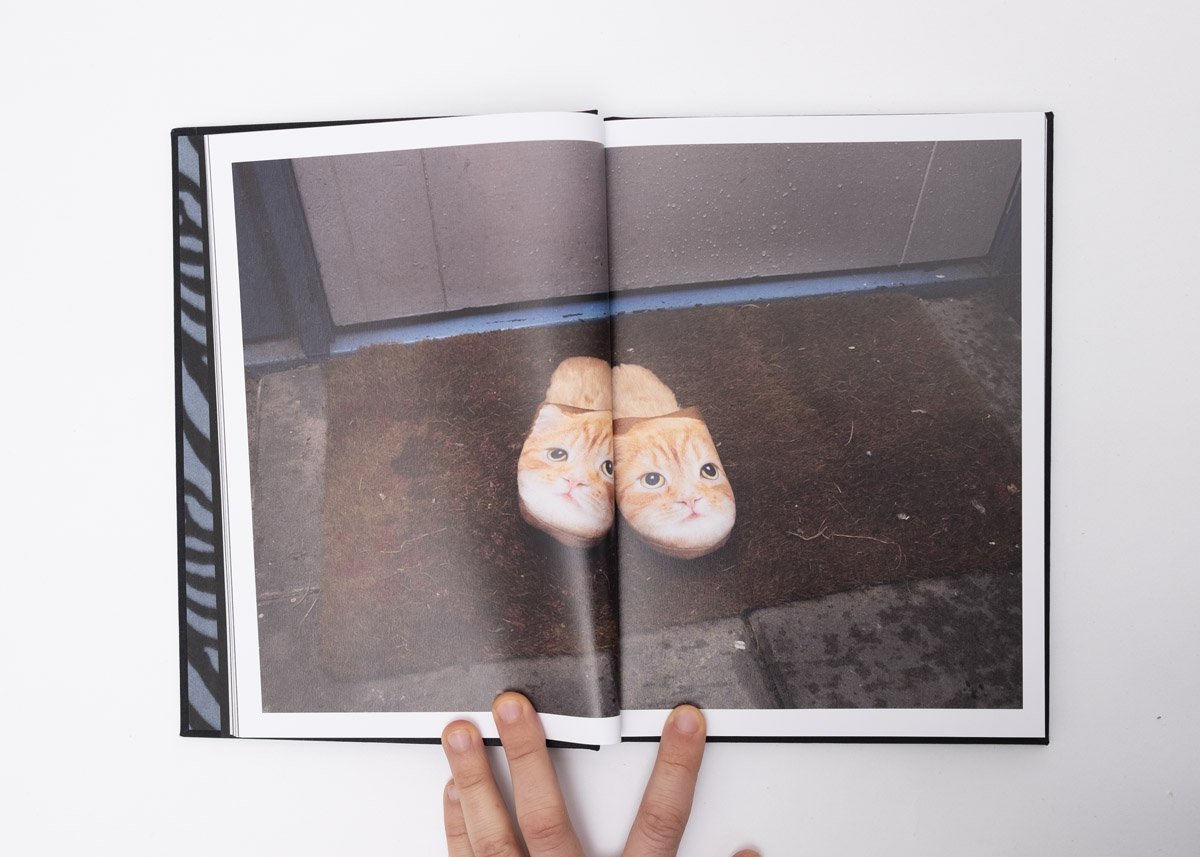

It is a beautiful spring day outside and the paper cranes that rest on my windowsill are fluttering. Delicate victims of the breeze, they fall one-by-one and their poses, which are primarily variations of resting on one delicate wing or the other, remind me of their referent, a crane in the sky that leans to turn. To my right, I remember yet another legion of figurines that I've collected; these ones are cats and dogs sourced from the dollar store and they keep watch over the kitchen. I like to think that they have an amicable relationship with the cranes, which they face. The first found photograph in Annegien van Doorn's Biophilia is an image of orange tabby cats emblazoned across slide-style sandals; I watch my own gray tabby stalk across the house and think about all of the images that I've made of her over the years. I find myself asking a question that I have neglected to ask previously: what, exactly, are these things, these incessant approximations and references to the natural world, for?

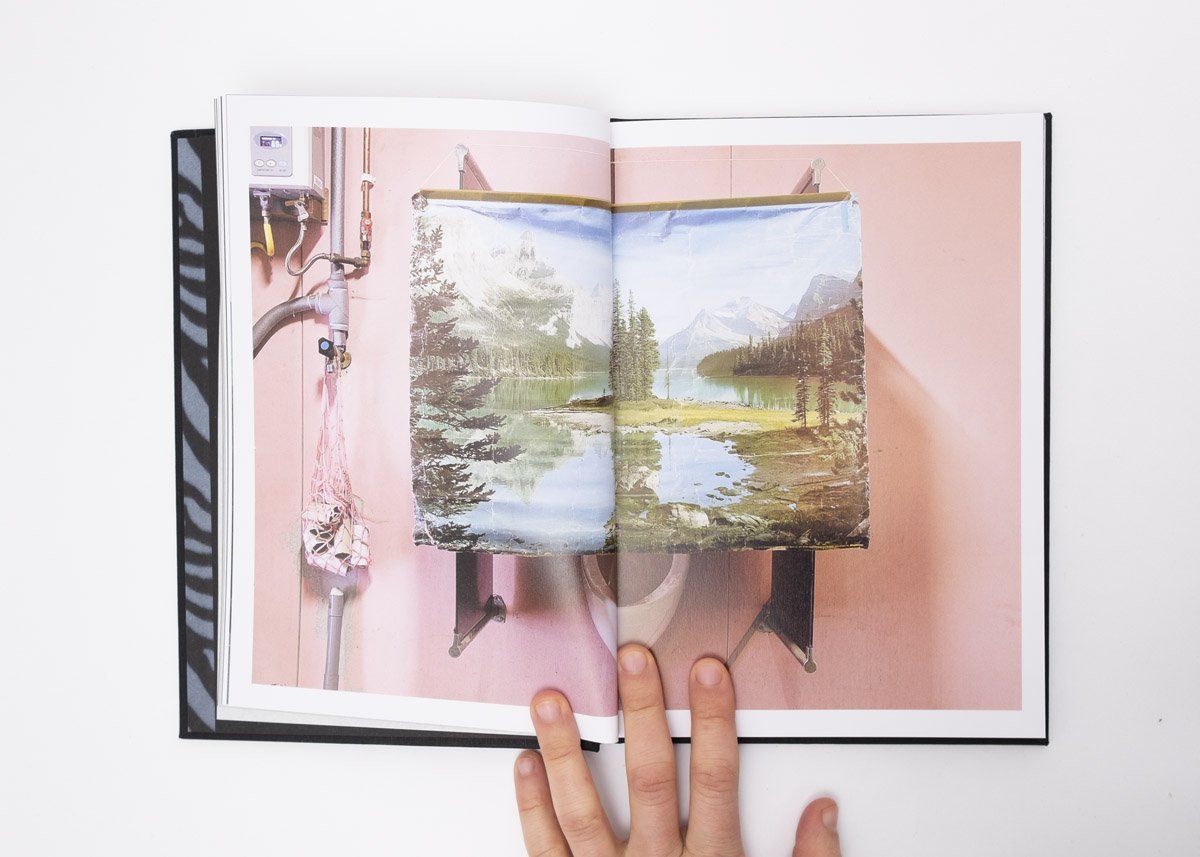

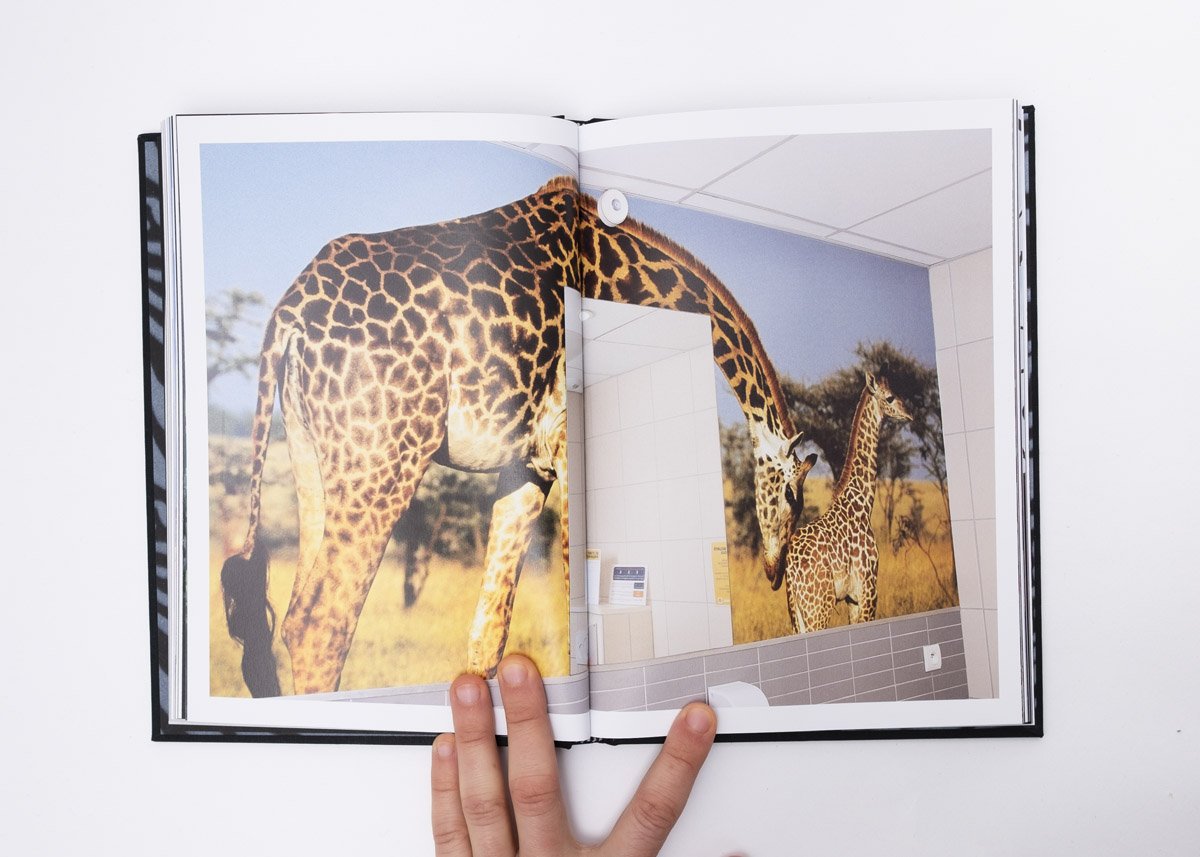

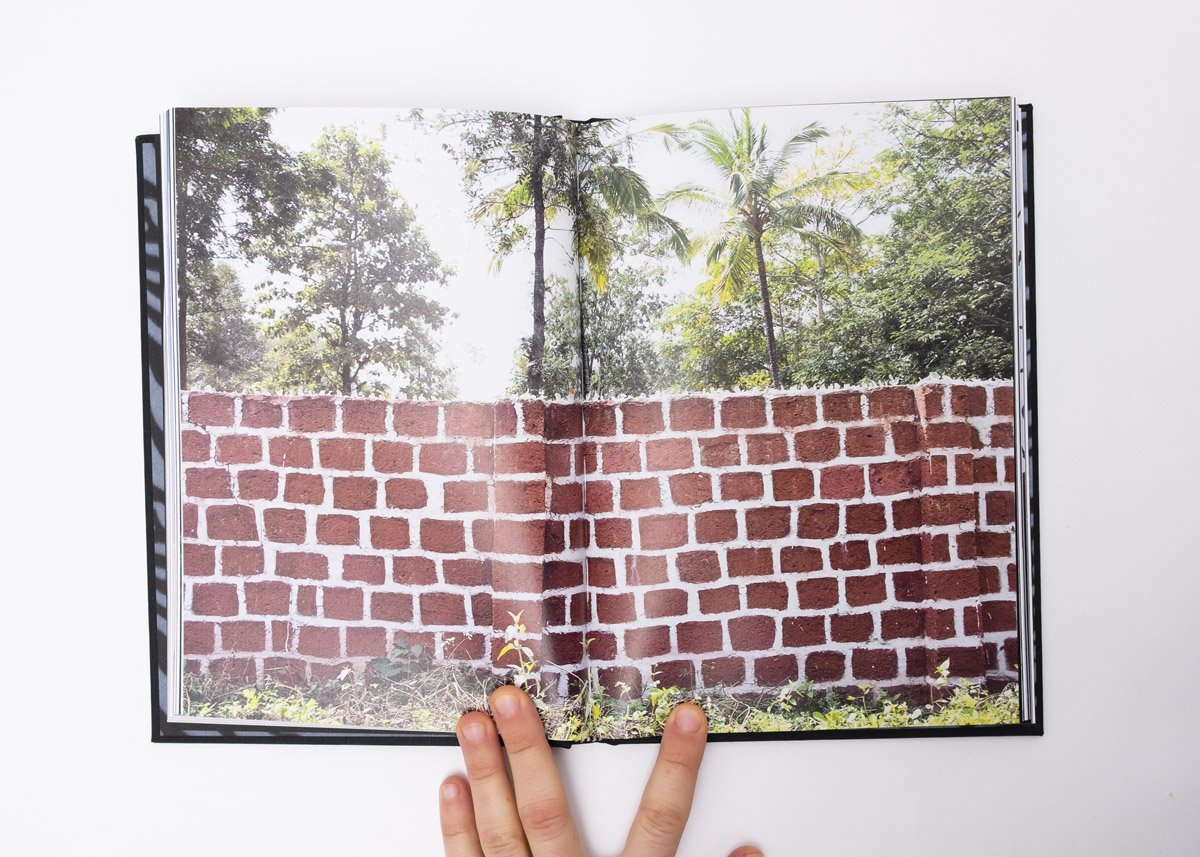

Biophilia is a self-published project from Dutch photographer Annegien van Doorn that examines invited environmental intervention(s) into our constructed and curated interior spaces. In the western, industrialized world, we have been relatively successful at establishing what is categorically "inside" and "outside", though this is a distinction that the artist tests throughout the duration of the book. What happens, poses van Doorn, when we condense mountain ranges into wall-size stickers? When waiting rooms mimic the sublime language of the Hudson River School of painting?

The answers to these questions are truly delightful.

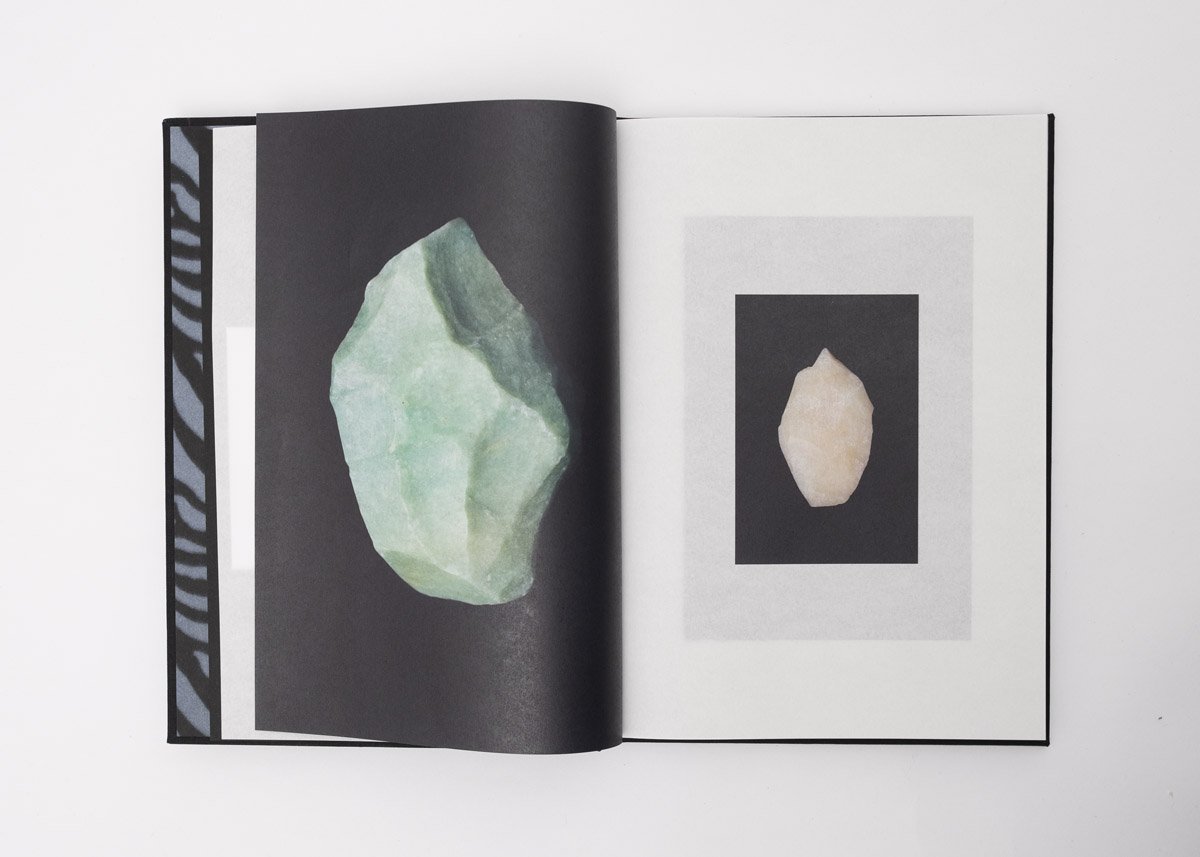

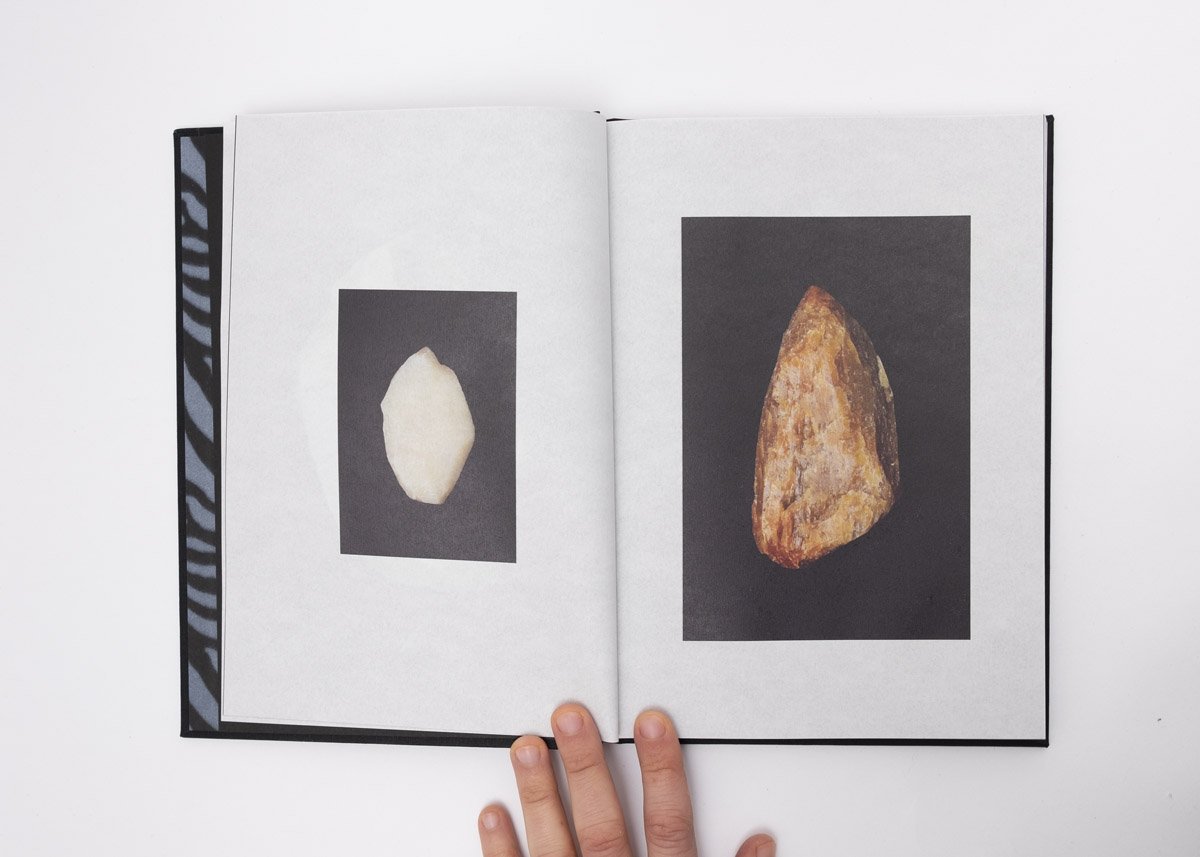

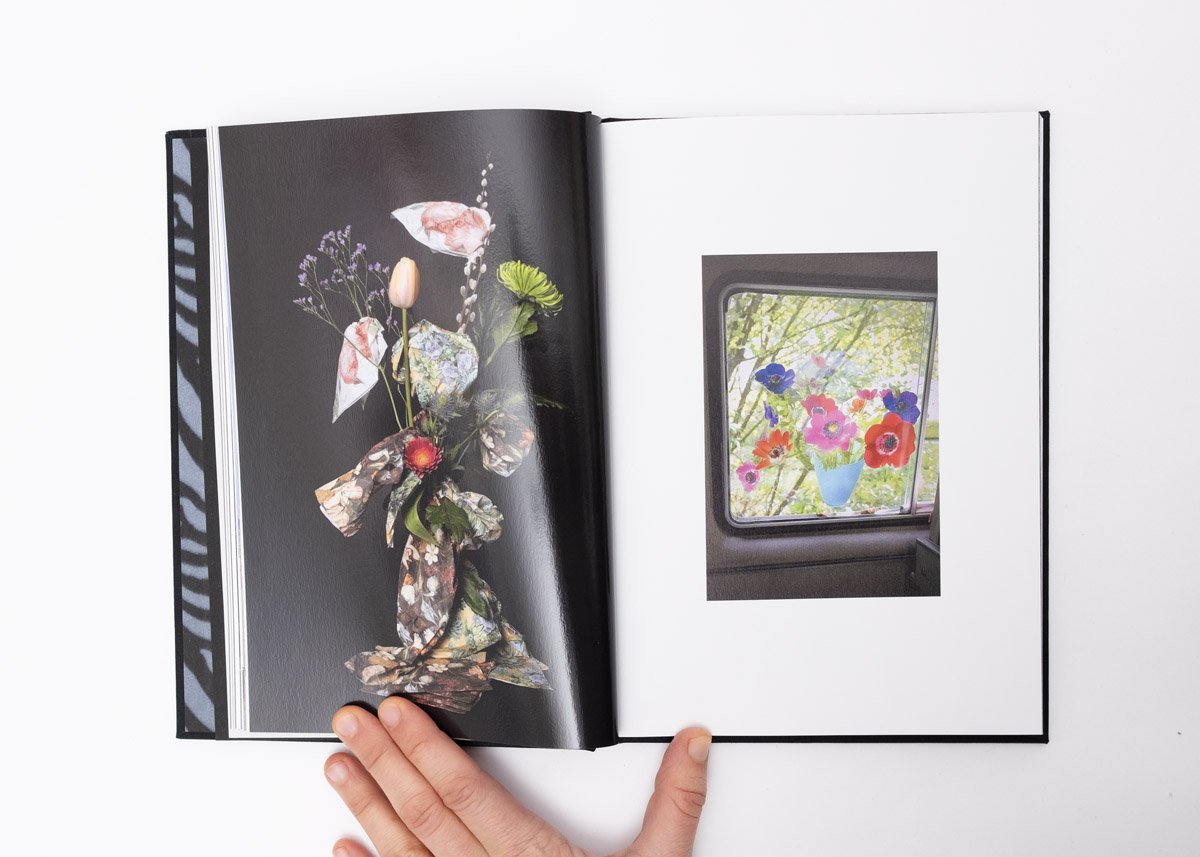

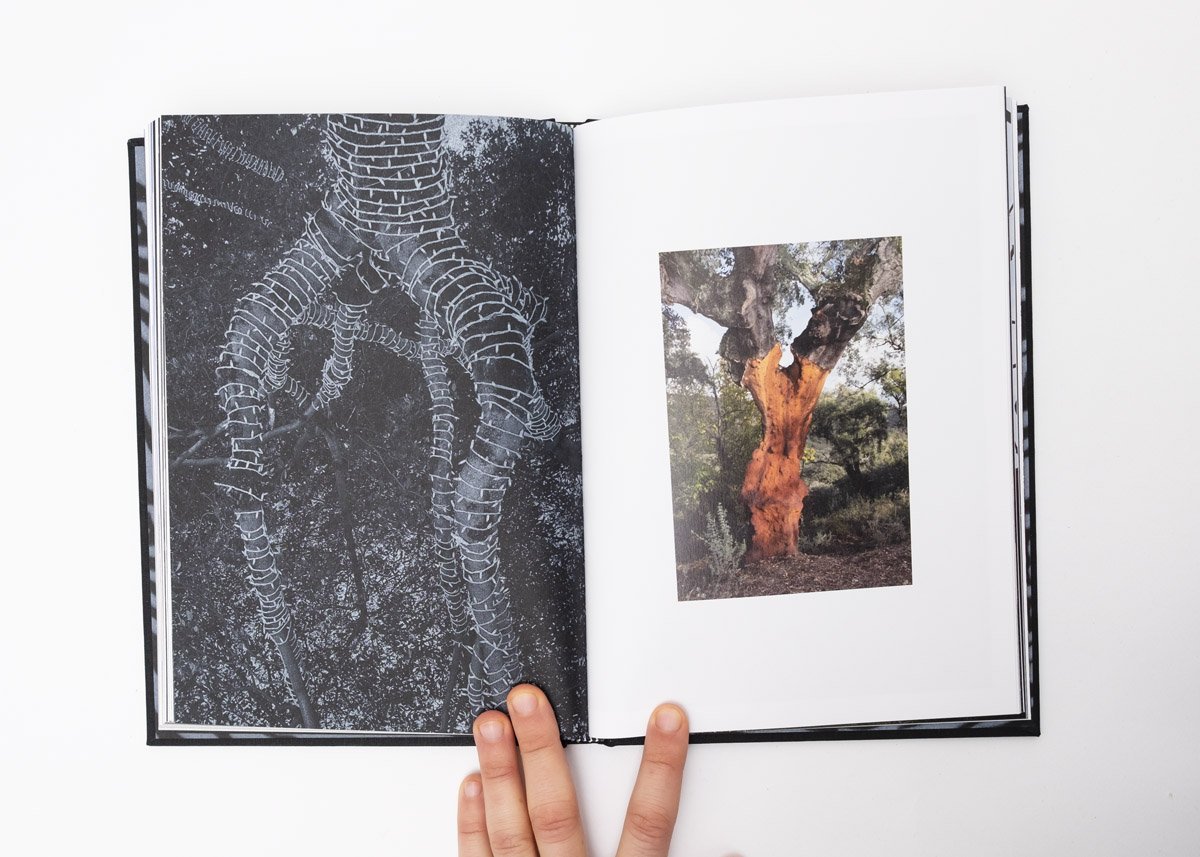

I find myself returning to the opening images of Biophilia often. A series of still life images starts the book off, the fronts and backs of crystalline objects printed verso/recto on a lightweight paper. Initially, I was convinced that these small, faceted rocks were what they seemed, but now I often wonder whether or not I’ve been fooled by very convincing rock candy.

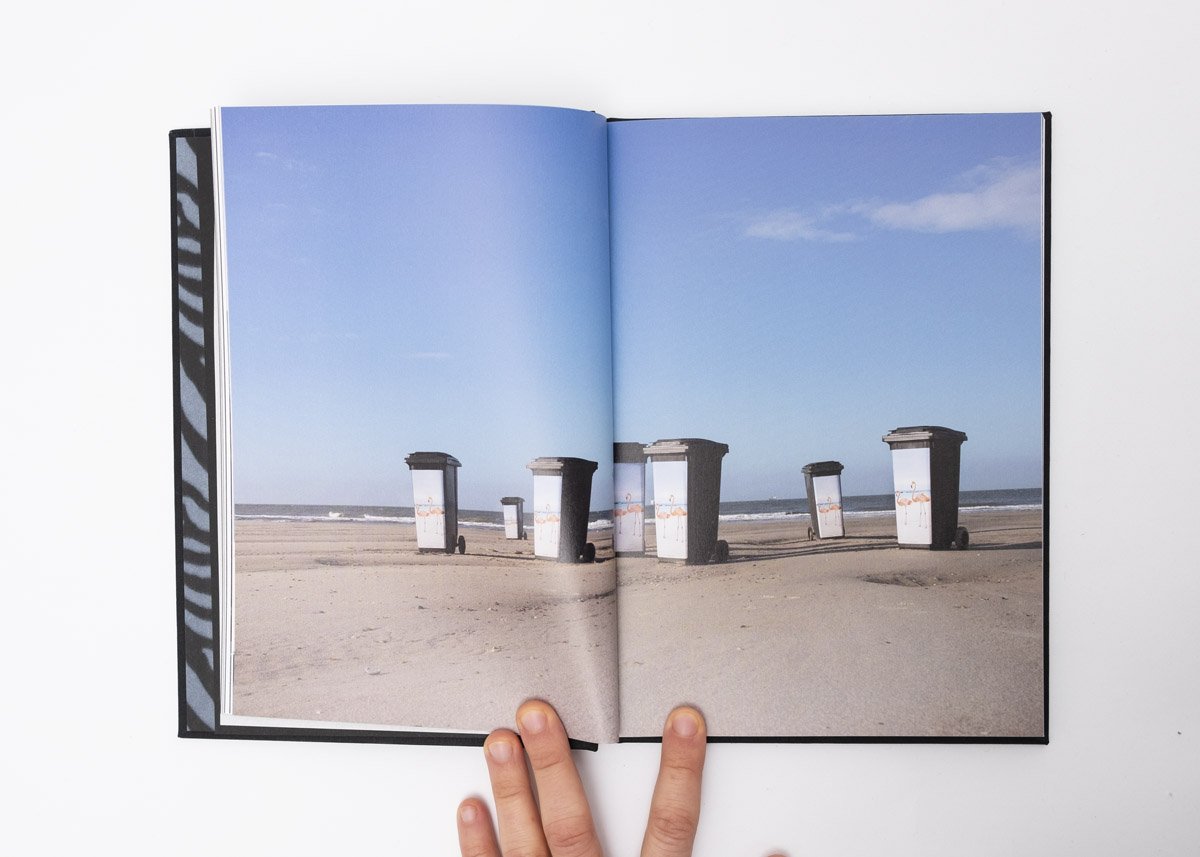

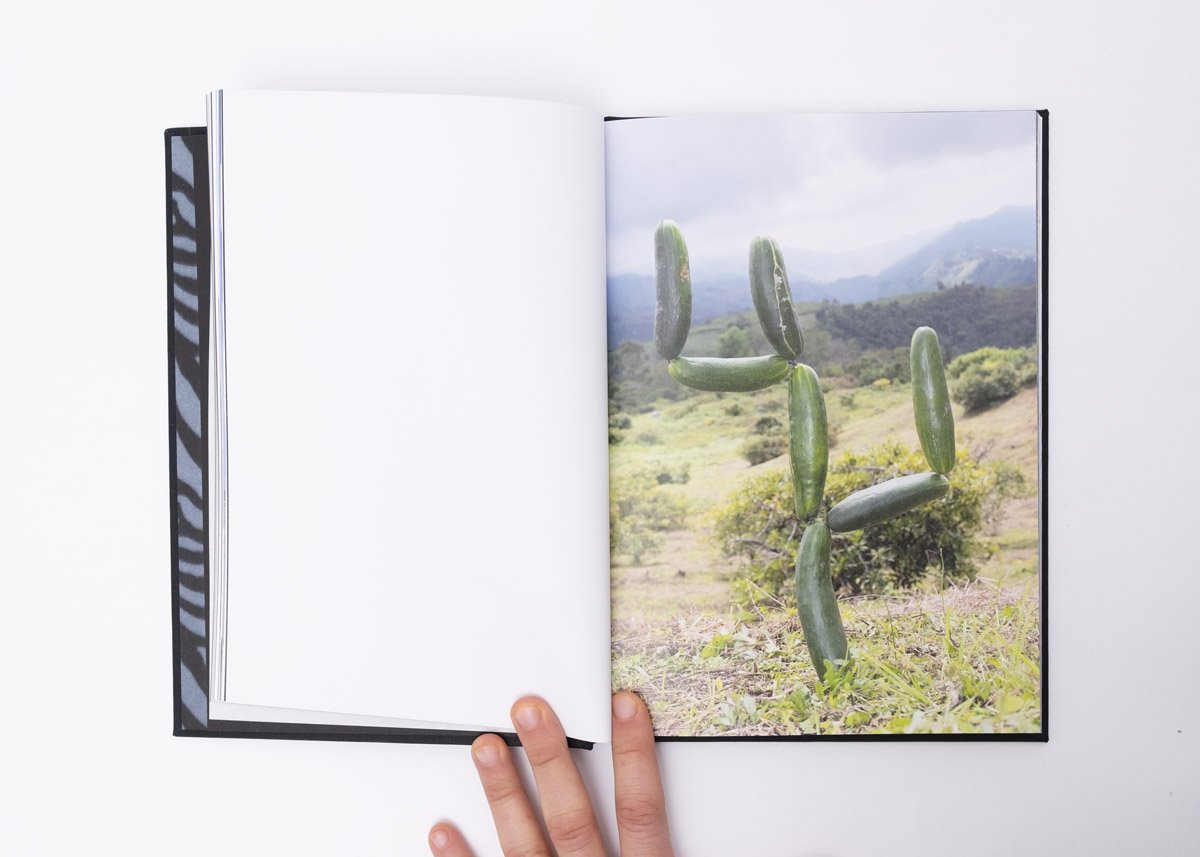

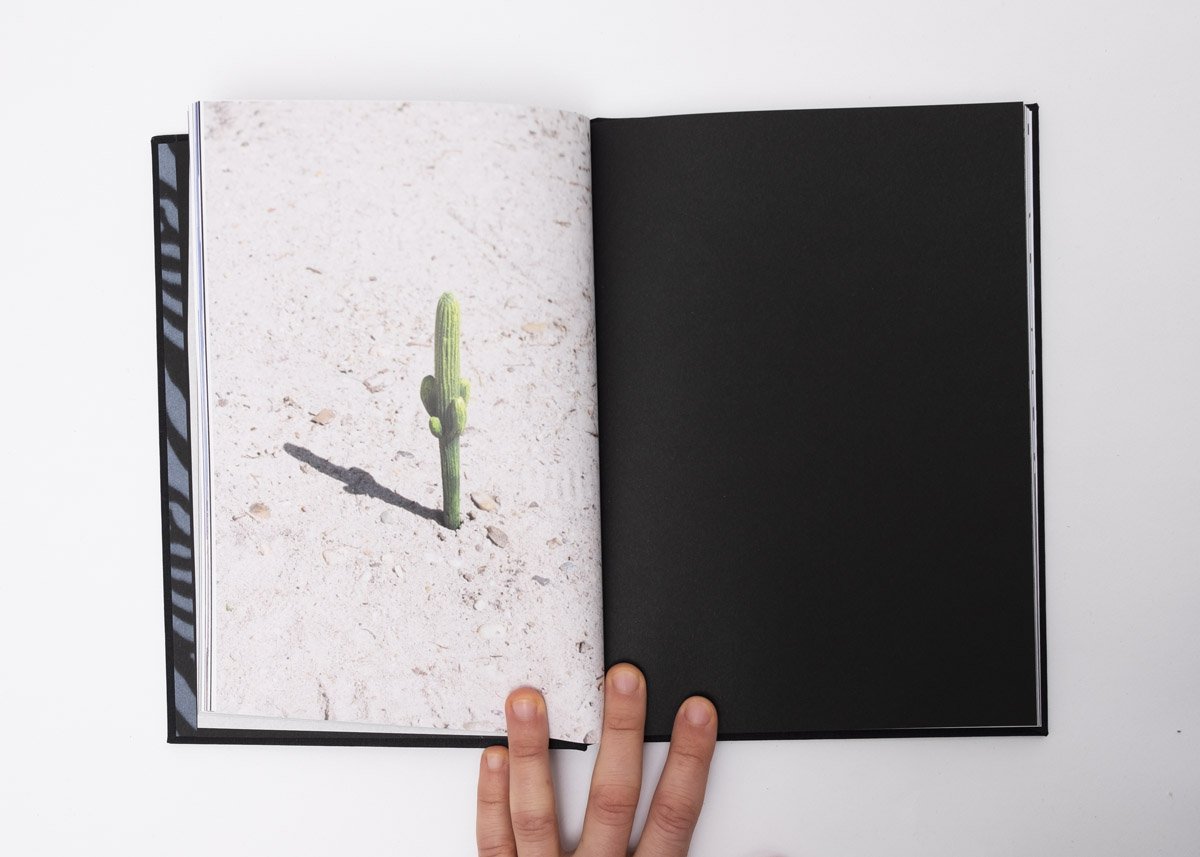

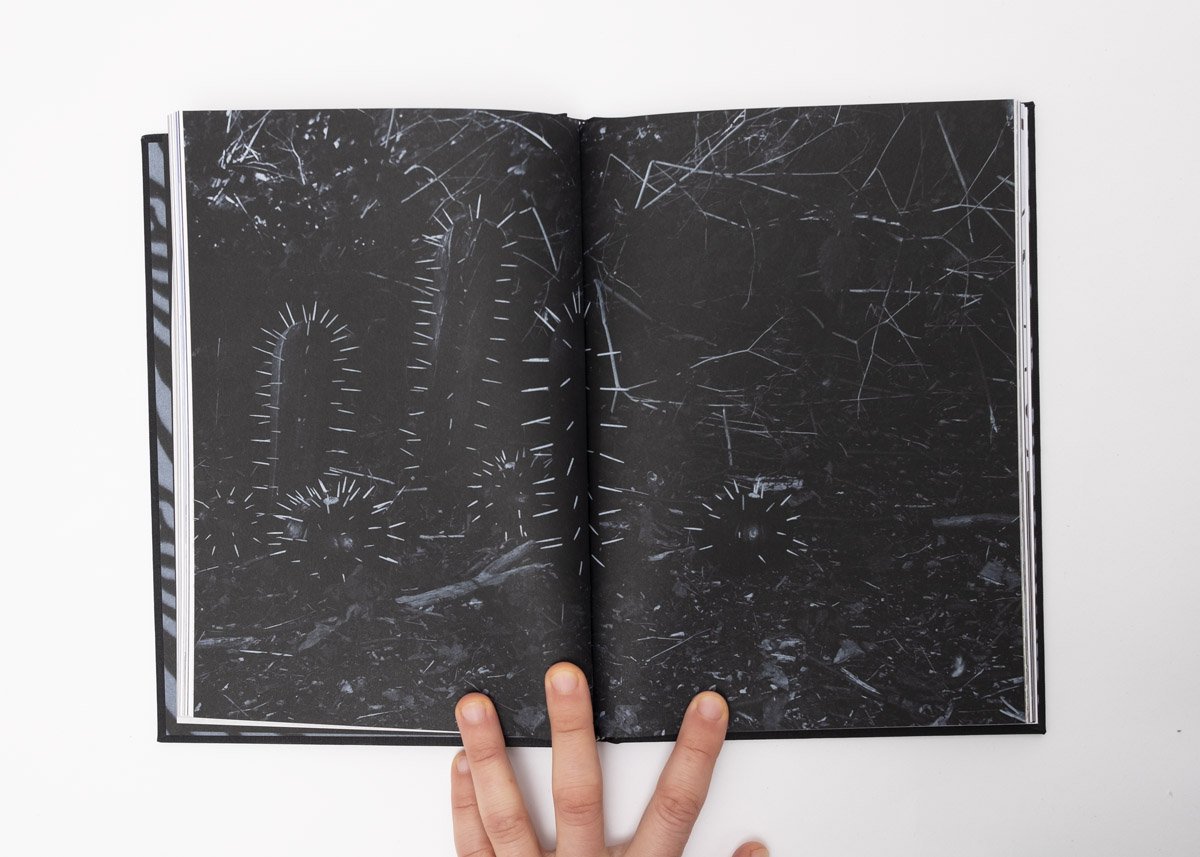

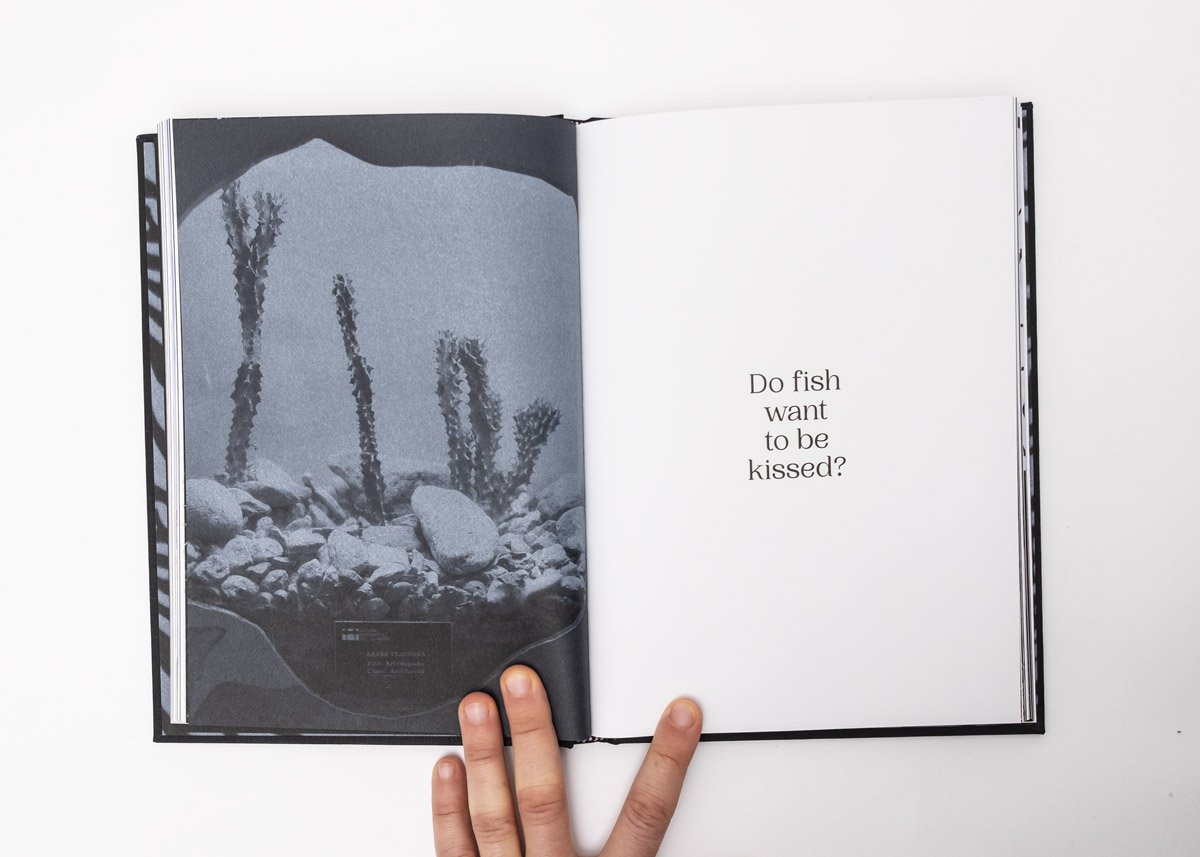

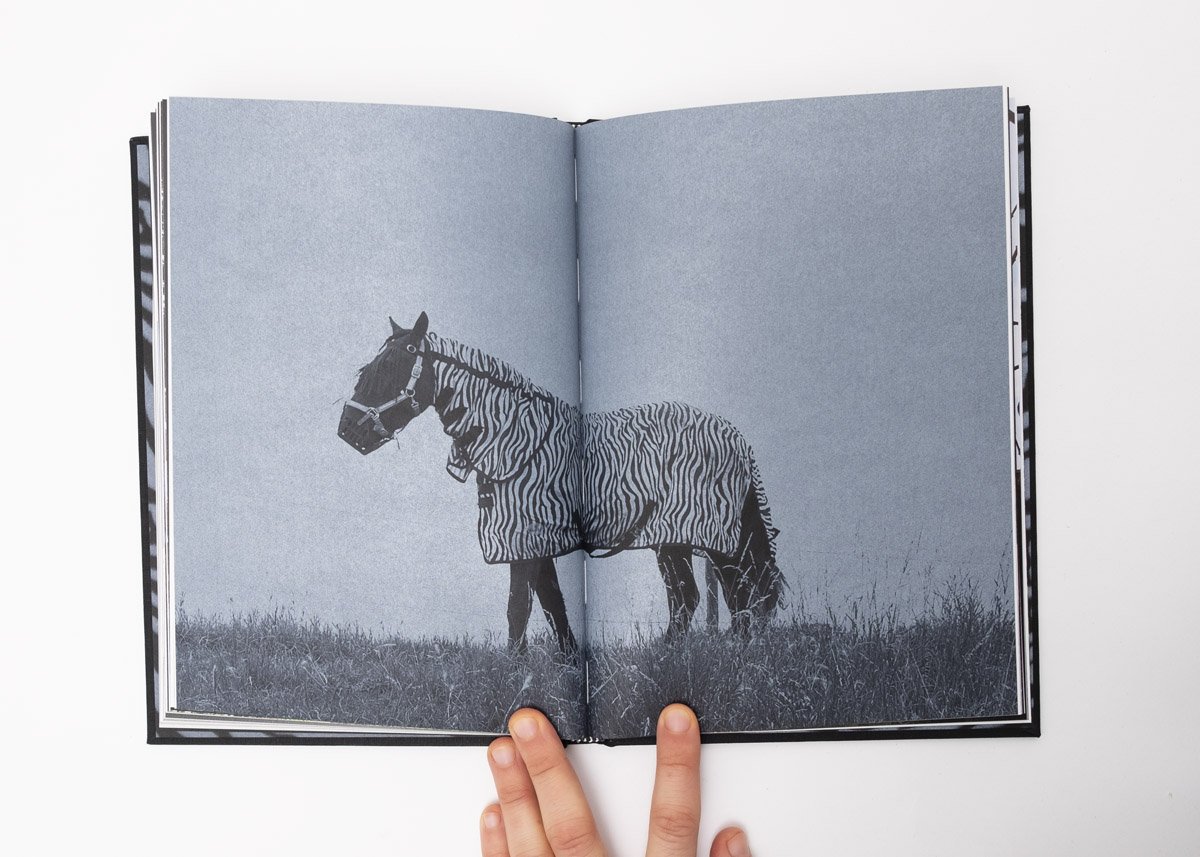

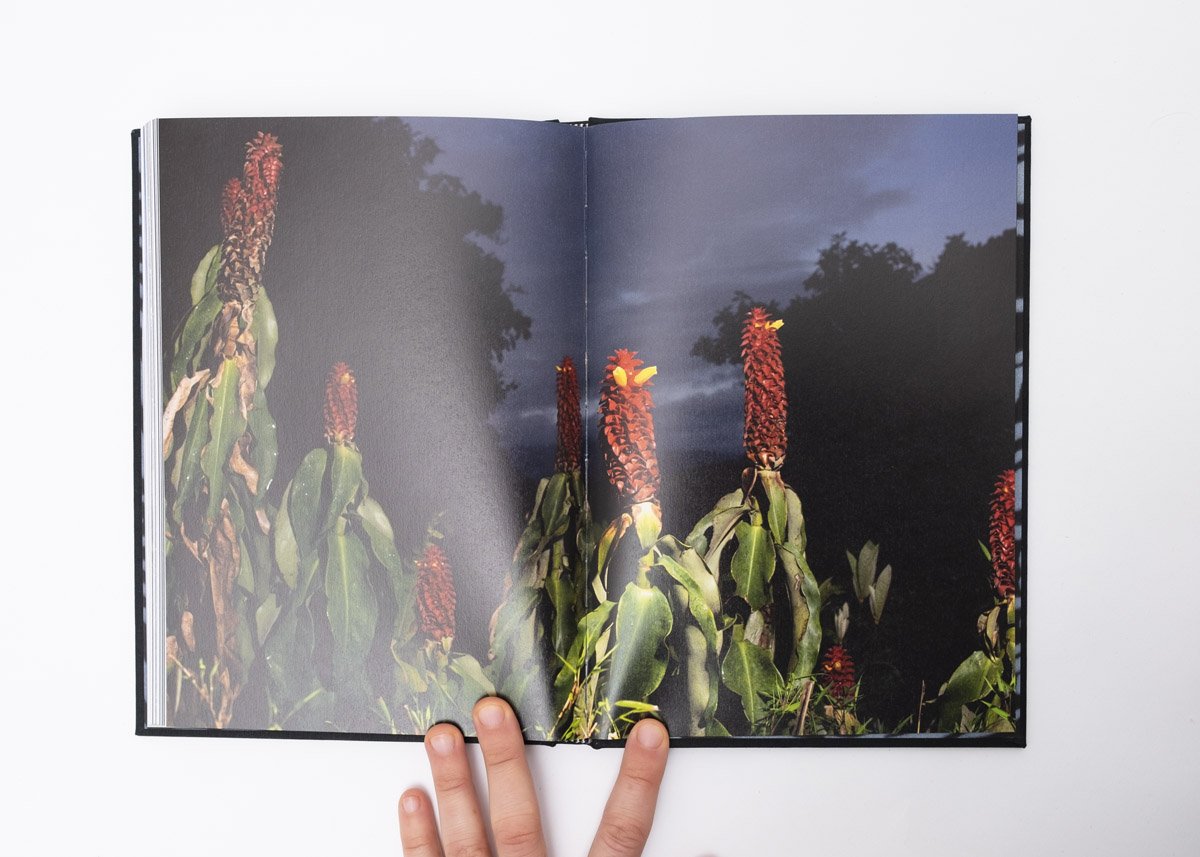

The images presented to us in Biophilia are masterfully sequenced as to blur the line between what is constructed and what is captured. This version of nature is truly postmodern and there is no “straight” representation of landscape in this book about our relation to landscape. A horse stares ahead, draped in the colors of their close cousin, the zebra. Posed cucumbers stand in for a saguaro cactus and birds flit around a bench that holds itself up with approximations of the bodies of swans. A tiger umbrella posed in dense shrubbery proves to be an effective stand-in for the real thing while plastic seashells co-mingle with their ancient cousins on the beach.

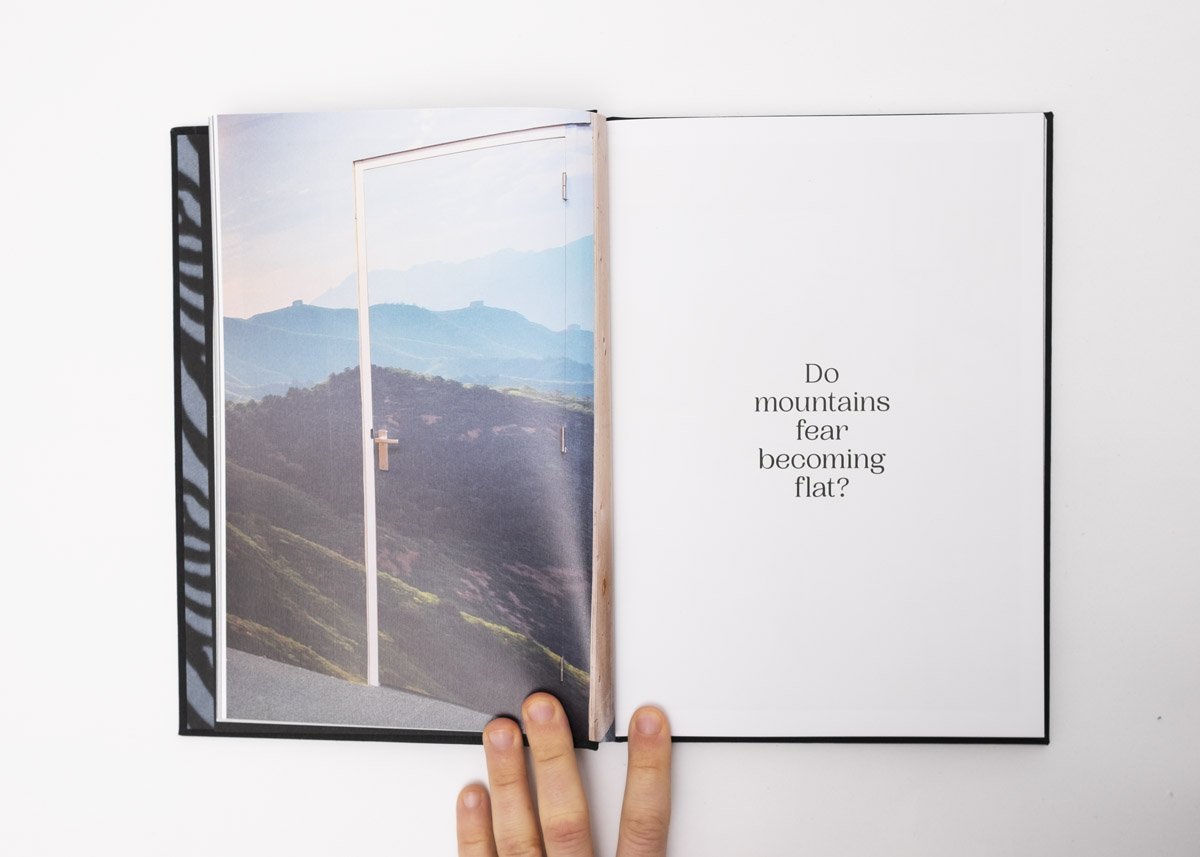

Interspersed between these pictures are literal questions. “Do mountains fear becoming flat?”, asks van Doorn, “Are plants individuals?,” “Do wild animals think pets are softies?” I am so enamored with these questions because they call attention to the active construction of an emotional world that is linked to the landscape. These small quips provide the reader with opportunities to reframe the way that they have related to the natural world without inviting them to claim it. In order for us to address these questions, we first have to acknowledge that we do not occupy the same emotional world as mountains or plants or pets.

There is an undeniable relationship between photography and colonization of both landscape and people; part of what enables this is the anthropomorphism of the natural world, or the assignment of human traits and feelings to systems and objects beyond them. This act of assigning mutual understanding creates the sense that we are more “connected” to the land than our neighbor, who may not project the same sentiments. We feel something in common with the land, we think, and so our relationship with nature is more important, deeper, more spiritual than another’s. These pictures subvert that idea because the construction of this project is so apparent; all of these examples are transparent attempts at bringing the “outside” to the “inside,” of attempting some sort of inter-species or inter-object singularity, though most of them do the exact opposite by making those categorical divisions humorously apparent.

These attempts at melding the natural and domestic are examples of humanity’s anxious attachment style, a method of claiming that is driven by clumsy, fervent love rather than calculated force (for better or for worse). It makes sense to me as I sit back and look around my own home, littered with figurines and thrift store landscape paintings and houseplants (which I could never manage to keep alive until recently), that my acquisition of all of these things may be related to my desperate fear of losing them in their proper contexts.

My suspended state of ecological clinging is undoubtedly influenced by my own sense of biophilia, a literal and obsessive love of things alive, and Annegien van Doorn’s images are a triumphant and defiant ode to the environmentalist kitsch that we engage with for decoration and for pleasure.

Boiphilia is available here.