Q&A: Alicia Rodriguez Alvisa

By Hamidah Glasgow | March 24, 2022

Alicia Rodriguez Alvisa is a Cuban visual artist currently based in Miami, FL. Alicia graduated with a BFA from The School of The Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University in May 2018. She is the recipient of the Springborn Fellowship and The Yousuf Karsh Prize in Photography in 2017. Her photography work has been exhibited throughout the Boston area at AREA Gallery, Bromfield Gallery and three consecutive Medal Award Galas at the MFA, Boston; and internationally in Sanlang Art Dimension (China), The Auckland Festival of Photography (New Zealand), Palazzo Ca Zenobio, (Venice Biennale 2019), and in her home country Cuba with her solo show Dale Con Todo at the Biennale of Havana 2019. She has performed at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA, Gallery Kayafas Boston, MA and The University of Ohio. Her on-going performances & public interventions include her series of performances I Can Look Strong, I am Strong, in which she becomes “Strong Arm”, a genderless bodybuilder who talks about issues of gender, identity, and race in the contemporary art world while lifting weights and wearing high heels.

Hamidah Glasgow: Alicia, It’s been a pleasure working with you on The Horizon and Everything Within It exhibition at the Center for Fine Art Photography. You come from an artistic family and have collaborated on performance art with your mother from a very young age. Tell me more about your trajectory as an artist?

Alicia Rodriguez Alvisa: If I look at this, through my experience with art, the influences I've had, and genetics, I'd say my trajectory as an artist started when I was a kid. I grew up in a house full of artists. Both of my parents are visual artists, and at the time, my dad was a professor at the Art Institute of Havana, so my house was filled with fellow artists of my father and many of his students. My parents also hosted classes, critiques, and even conferences weekly. It's funny to think that as I was growing up, I saw what a hustle it was to be an artist in Cuba nonetheless, with so few resources, and I somehow avoided becoming one, I even repelled the art world in some ways.

I've always been very creative. I loved drawing and taking pictures as a kid. I remember when I was about 13 or 14 years old, I decided I wanted to study either interior or fashion design, and I thought, well, this is artistic enough, but it will definitely give me much more stability. So for many years, I prepared myself for the exams to get into a very good design school in Cuba, and I got in! And I loved it. I fell in love with what was the beginning of my design studies.

In the middle of my first year in design school, I had the opportunity to apply to the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and Tufts University in Boston. I was very hesitant as I didn't see the word "design" in the school's name, and I was certain that all I wanted to do was design. I went to visit the school, and I loved it. I immediately clicked with the environment I saw… the classrooms, the painting, drawing classrooms, the photography department and the darkroom, and so much more. I never saw that level of professionalism in a school setting, especially me, someone from a third-world country, someone from Cuba. I could only think about the possibilities.

People who guided my tour knew that I was interested in design, so they knew how to get me excited about it, knowing that I could cross-register with some design schools in Boston, and you know I said yes. I went all in. I started classes at Tufts in 2014. But even with all this excitement, when I was in school, I didn't see myself as an artist, not yet. So I took all these design classes, and then I got into a photo class with Claire Beckett, who is still a mentor for me, and everything changed. I absolutely, 100%, fell in love with photography and its process, and I said, well, there's something here…so I continued taking photo classes, and I realized I was good at it, much better than I thought I was. I knew I always liked taking photos, but this was so much more than that. I couldn't/wouldn't stop thinking about photography and seeing the world, my world, through the lens, just completely absorbed me.

The amazing thing about the school is that, at the time, they had an open and free curriculum so that we could take any classes, from photography and performance to video and drawing… and I took them all! I started to learn more about all of these mediums I was interested in, and I just let myself go if that makes sense. I went from rejecting the idea of being an artist to wanting to explore all of my possibilities and see how far I could go with all the knowledge that I came across from being my parents' daughter in a vibrant art world environment, plus all the new things I was learning.

As I started to immerse myself in all of these new, and somehow not so new, ideas, I started realizing my interest in performative work. At the same time, I faced a whole new life outside of Cuba. Everything was so different. The culture, more than anything, was something else entirely. It made me realize that I am, amongst other things, a person of color. In this new country, I am considered a minority. While back in Cuba, I was not. It shaped how I was treated and still being treated. For an adult, who has migrated here, maybe all of these things don't seem like a big deal. But for someone who was still a teenager, going through a self-discovery journey, away from everything that grounded me… it was a huge deal. So the navigation through these "new" aspects of my identity started appearing in my work.

And once I saw that things were coming together and that my new skills allowed me to portray my experiences, my confidence as an art student increased.

Having great mentors at school, plus my parents, who always pushed me to have a high level of rigor and commitment, helped me make powerful work since I was still at the Museum School.

To this date, most of my late college work is still exhibited and recognized.

Things have changed tremendously since I left Boston in 2019. The pandemic hit us. I moved to Miami after being in Cuba for five months. The economic situation we have faced as a country in the past few years… Everything has impacted my process.

I found myself jobless in 2020, and I decided to open my own health and fitness coaching business, following the other two of my passions, fitness, and nutrition.

It has been quite the journey, as I had to put my art practice on hold for a year.

However, I see my coaching practice as an extension of my art practice. The process is rooted in teaching, empowering, and helping women tap into their best selves through mindful eating, fitness, and mindset work.

I like to think that my art empowers women on a broader level, whereas my coaching empowers women 1:1. And now more than ever, I know that one feeds off of the other, and something very powerful is taking shape/developing, and I can't wait to see what "this" becomes. It's all connected.

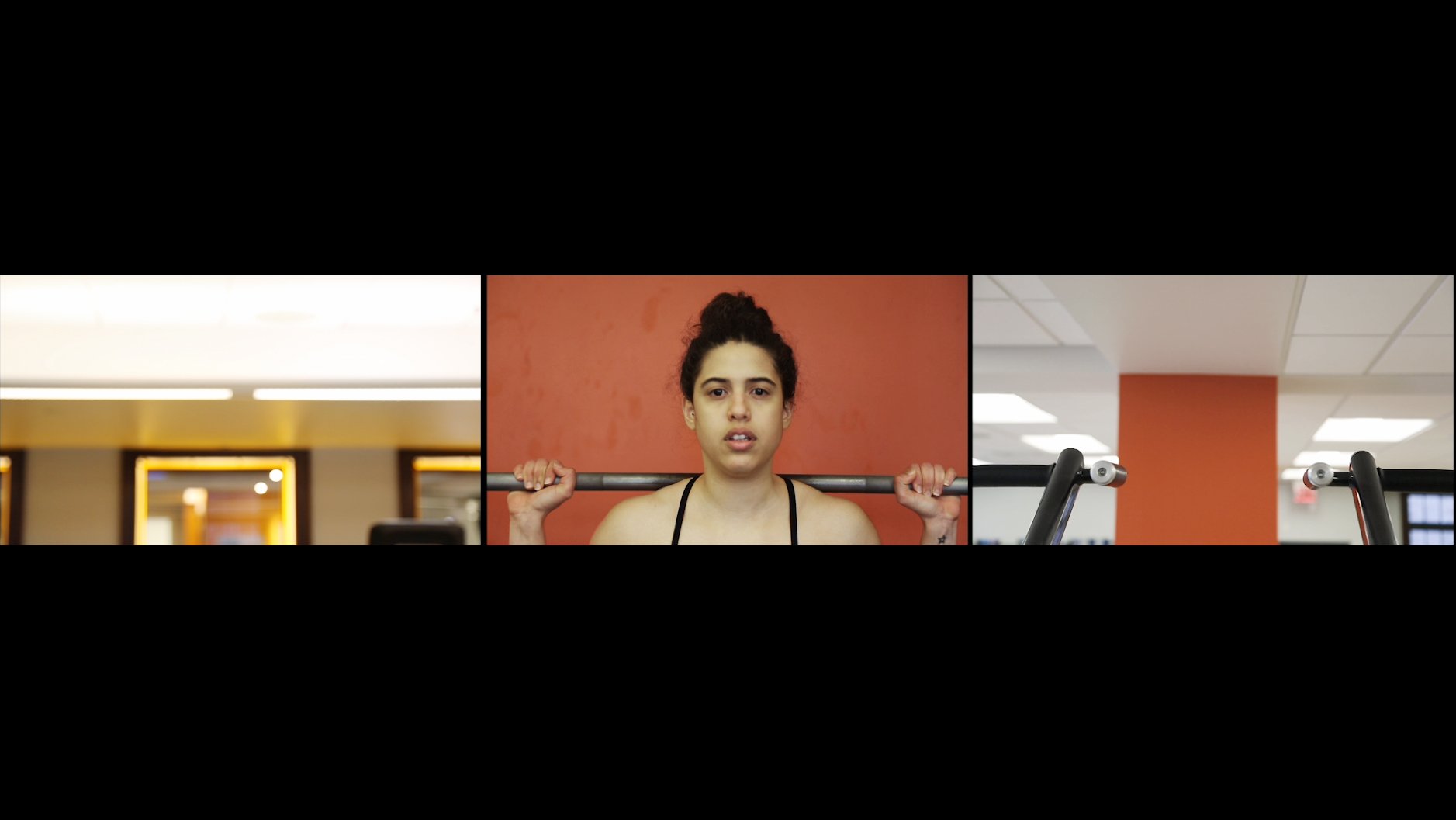

Installation Image of Challenge

HG: Your video work, Challenge, explores your early college experiences and the awareness of your 'identity' through the lens of other Americans. There is a correlation between your strong feminist work and how you are strengthening your body at the gym throughout the video. I'd like to hear more about these relationships.

ARA: My feminist work started in college here in The United States. In Cuba, I knew about the feminist movement, and as a teenager, of course, I celebrated my gender and my friends. I understood the concept of machismo because growing up in Cuba, that's the norm that we grow up in. However, I didn't have an accurate idea of what feminism actually was until I got to the United States and started informing myself about feminism and its roots. And most importantly, about society's issues when it comes to being a woman and the obstacles that we face as people, professionals, family members, friends, etc. I realized the topic was much more profound than I thought.

Simultaneously, I had always been passionate about fitness. I loved working out, going to the gym, etc. However, on the one hand, there was always something to feel uncomfortable about at the gym, no matter what gym I went to, there was always a guy looking at me, a guy trying to flirt, a guy not respecting my space, congratulating me for even being there, or lifting more weights, etc. Putting up with this is uncomfortable, as it is to navigate any day as a woman.

On the other hand, at that time, my passion for the gym was rooted in the fact that I wanted to be skinnier. And for a long time, I didn't feel that this was wrong, but the more I experienced life as a young woman and a person of color in this country; even going back to Cuba with this new knowledge that I had about my gender helped me realize how my use of fitness was making me shrink and take less space when I knew that my responsibility was the opposite. It was to take more space and to raise my voice and possibly race the voice of others, and what better way to do that than through my art.

I have suffered from body dysmorphia since I can remember. The idea of getting thinner was something I started working to overcome in therapy. And the combination of therapy with feminist studies in college allowed my relationship with fitness and the gym to shift.

I started to train for strength, and the more I focused on this, the more I experienced a sense of power. I was able to step into a room where a man's presence is so dominant, and I could step there with complete confidence, knowing that I could even lift more weights than other people there.

I remember as I tapped into these new feelings at the gym how I started seeing a direct resemblance of my empowerment with my own experience navigating my day-to-day environment—wanting to become louder, more powerful, wanting to take more space and share my experience with others.

So for me working out at the gym, getting stronger, increasing my confidence, showing other women that the gym could also be our space became part of my identity and feminist work, without even putting too much thought into it.

The resemblance was there, and I just needed to connect the two and let them unravel.

HG: How do you understand Cuba and being an artist in Cuba after living in the states for a long time now?

ARA: This is a very difficult question to answer, as there are two faces on this coin.

Going back to Cuba with broader knowledge about feminism, women, queer, and POC issues was hard. I felt that I didn't belong there, and my art couldn't be understood as I intended it to be.

I did a solo show during the Havana Biennale in 2019 called Dale con Todo (Give it your all). This show included some photography, video, and performance work. All based on my experience as a woman, an artist, a person of color, and my journey to empowerment in The United States. The show was well received and celebrated.

In fact, one of the pieces in the show was Challenge. Many people had questions and comments about it. Such as, why do you feel you are black? You clearly aren't black; you have clear skin… What's so tough about being a woman there if that's the country of opportunities?… etc.

At a point, I felt that I wasn't understood. However, how can I expect that when I know, I would have been asking the same questions if I had never left Cuba before?

This experience motivated me to create more work to educate Cubans on this topic. I came back to The States wanting to make more art, and instead of sharing my experience with others, it shines a light and helps Cubans in the island understand the real struggle the Cuban diaspora goes through.

However, with the same impetus that I wanted to do, all my motivation to do it went away very fast.

I'm not sure if you are familiar with Cuba's stand with art.

In 1959, Cuba became a communist and socialist country. This ideology wasn't only established as a form of government, but it was also established as the only ideology for every single person on the island. We weren't, and we still aren't, allowed to think and express ourselves differently than how we were taught. And this applies to Art and Culture in Cuba as well. Any political work that goes against their guidelines is banned, as well as the artist. That always existed, but it wasn't an official rule per se.

However, in 2018 the government took a strong and official stand against political art, applying Decree 349 in the Constitution. This is an excerpt of Decree 349:

"Under the decree, all artists, including collectives, musicians, and performers, are prohibited from operating in public or private spaces without prior approval by the Ministry of Culture. Individuals or businesses that hire artists without the authorization can be sanctioned, and artists that work without prior approval can have their materials confiscated or be substantially fined. Under the new decree, the authorities also have the power to immediately suspend a performance and propose the cancellation of the authorization granted to carry out the artistic activity. Such decisions can only be appealed before the same Ministry of Culture (Article 10); the decree does not provide an effective remedy to appeal such a decision before an independent body, including through the courts."

This is clearly a decree that serves as a filter for the kind of art they allow artists to make and exhibit.

This decree happened the same year I graduated from college, and right after the Cuban president signed this decree, many artists started asking for it to be turned down. They wanted freedom of speech.

As a result, the decree was put into action right away, some artists were incarcerated, and the situation has gotten worse ever since.

After the pandemic, Cuba hit rock bottom. The country is going through one of the worst economic crises in history. People don't have anything to eat; whatever food is made available for sale is almost impossible to buy because of the high prices. The hospitals are in horrible conditions, and the situation is quite critical.

In 2021, the health crisis hit, hospitals were flooded, and everything got worse. The people went to the streets in several cities to peacefully ask the government for help, for them to do something to improve the situation. Many artists also spoke up on social media platforms and went to manifestations. And instead of helping, the regime started arresting people, including many artists whose political art had been questioned and banned before and now were part of this movement mainly triggered because the people of Cuba had had enough.

Long story short, the lives of artists are in constant threat. I have friends and acquaintances who are still in jail after these events. While the country is under surveillance, the art world is also under extreme scrutiny.

I haven't been to Cuba since 2020, and honestly, I even fear stepping foot into the airport.

So after living in The States, my understanding of Cuba is that there's a LOT of work to be done.

In people's minds, and in the country itself.

When will we have the opportunity to turn things around?

We don't know…

For now, all we can do is support them, do our work on our side of the world, wherever we are, and suffer from afar, hoping to go back one day thinking that we will be able to go back for good.

HG: In your series, You Are There, Are you there? There You Are, There is a sweet tenderness between the figures. Where did the idea come from to photograph yourself as both figures? I'm sure that you've heard the comparison with Kelli Connell's work, Double Life.

ARA: This series started in 2017 when I was in college.

The minute I brought my pictures to critique, my teacher brought up Kelli Connell's work. I hadn't seen her work before, and I wasn't familiar with her Double Life series. I fell in love with her pictures, and I even felt like why keep going with my series? However, I noticed how even though we are both double exposing ourselves, our works are very different.

Connell questions the sexuality and gender roles that shape an individual's self-identity in intimate relationships. There's a clear separation between the two roles she portrays, almost as if it wasn't the same person at all. Whereas in my series, it's essential to keep the idea that I am the two.

I spent years battling eating disorders and body dysmorphia. People who suffer from these disorders can understand the duality we constantly experience.

In how we feel about ourselves, how we eat, behave, think about ourselves when we look in the mirror, etc.

My body also changed quite a lot through my healing process from skinny to voluminous, as I always was before. Even though I was open to the changes and I had gotten to the point of acceptance, there were days it was hard to do so.

This series is an homage to the other Alicia who kept going, the one that, no matter what happened, still took care of the other, the one who stood up and took control, the very same one who showed the most confidence and empowered side when needed.

Therefore, from the beginning, the main idea was to tap into my two selves—the empowered and confident Alicia and the other Alicia, who was struggling with herself and her image.

The first drafts were too much yin and yang, quite literal. For instance, one Alicia is mad, and the other one is happy. But as I continued to tap into what those Alicia's really meant to me, the softness and tenderness started to appear.

Once I understood that it wasn't about one contrasting the other but rather one supporting the other, everything came together.

HG: What are you most excited about as you move forward in your art practice?

ARA: I'm experiencing a shift in my work, as I said earlier.

It's interesting to me how the concept of the two Alicia's has expanded unconsciously to my actual life, my real life.

As I've mentioned, I own a health and fitness business, and I've found myself making art in a very "unexpected" way. Through my coaching and helping clients, I've found many interesting areas to dig in and discover, and I see a lot of potential for future projects, so one could say. I'm definitely excited to bring both of my worlds together.

I want to combine my coaching practice with my use of photography, video, and performance. I have many ideas about how I could bring the two together, and in the back of my head, I know that they are already one and the same. I just feel there is "something" I don't know what it is yet; that needs to happen for me to see them click.

For now, I'm giving it some time to develop into what it could or already is. I can feel one world casting a stone and the other one responding in ripples and echoes, much like the two Alicia's.

Something quite palpable is happening in front of me, which I'm most excited about. Most people have one thing they are very passionate about. I am lucky enough to have two, and being able to combine them is just mind-blowing to me. The possibilities are endless.

HG: Thank you for your time and creative vision.

ARA: Thank you!

All images © Alicia Rodriguez Alvia