Q&A: sunny strader

By Jess T. Dugan | July 5, 2018

Sunny Strader (b. 1991) is a documentary photographer based in Los Angeles and Danville, her 35,000-person hometown in central Illinois. Sunny's work is inspired by her Midwestern upbringing and the West Coast culture of her adult home. She approaches her craft with journalistic flair, thanks to her time in the newspaper business. The primary theme in Sunny's work is dreams — the ones we chase and the ones deferred.

Jess T. Dugan: Hello Sunny! Thanks so much for taking the time to speak with me today. Let’s start at the beginning: how did you discover photography, and what was your path to getting where you are today?

Sunny Strader: Thank you for taking interest in my work, Jess + Strange Fire Collective. I never thought I’d be a photographer until I was required to take a photography course for my art history degree. And even then, I didn’t consider it a viable career option. My first job out of college was writing obituaries for the Commercial-News, my hometown newspaper in Danville, Illinois. Occasionally the editor would ask me to photograph people and events, which led to a job as a photojournalist at a bigger paper, the Rockford Register Star, in Rockford, Illinois. I stayed there for two years, and learned a lot about contemporary society.

Leaving journalism was difficult, but I wanted to explore the world of documentary — a world with fewer rules. So when I scored an assistant gig with filmmaker/ photographer Lauren Greenfield in Los Angeles, I packed my bags and left for California two weeks later. Today I focus on personal photography projects and gig on the side.

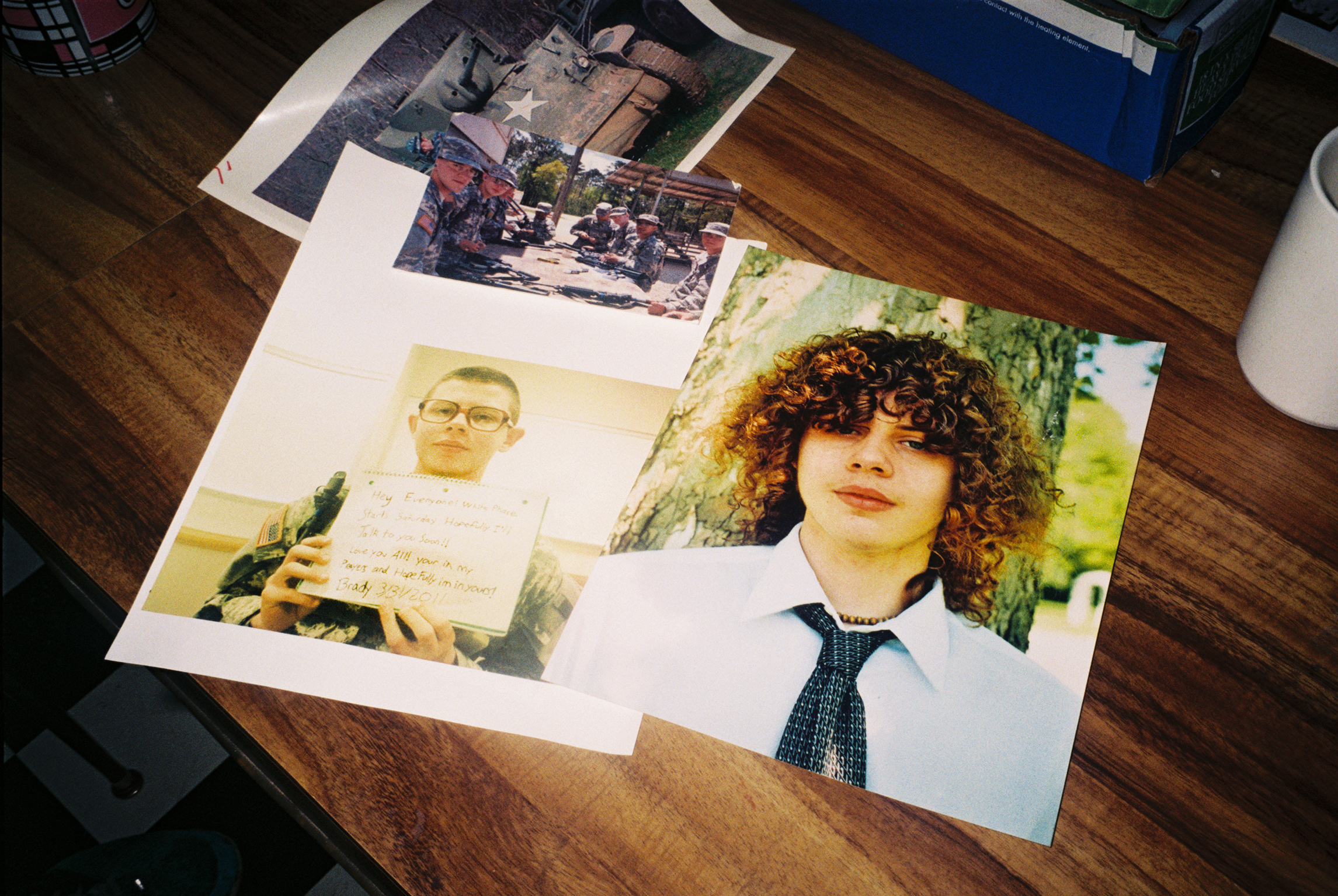

The MATS Project explores the adult lives of my fifth-grade classmates. Six are parents. Eight graduated from college. Nine live in Danville. Zero are married. And all have an IQ of 120+.

JTD: I recently discovered your work on Aint-Bad, and I was immediately struck by The MATS Project. How did this project come to be? What inspired you to revisit your fifth-grade classmates and photograph them and their lives now?

SS: Los Angeles overwhelmed me at first. I tried to pursue several stories, but struggled to forge any real connections with the people or the place. That’s when I naturally started to look inward, not outward. I had experience documenting communities that were quite foreign to me, but I knew that I’d have more conviction telling stories that were familiar.

There isn’t a specific event that inspired me to return home and reconnect with my classmates. Rather, it was the result of that reflection that naturally happens when one moves so far away from home, i.e. “who am I and how did I get here?”

Nesa dotes on her youngest child, Justus, in the family’s kitchen in Urbana, Illinois. Nesa and her boyfriend of three years, Jesse, raise the children and record music together in their home studio. In elementary school, Nesa wanted to be a singer like Keyshia Cole. “She totally got out of the ghetto, and that’s how I always wanted to be.”

JTD: The captions that accompany the images add so much to the photographs- it is interesting to me that you write about yourself as a documentary photographer but also reference your time working in the newspaper business. What is your process for deciding what to share about each person and photograph?

SS: Because much of this series is examining the past, The MATS Project is heavily reliant on text and captions. The first sentence is very much steeped in newspaper tradition. The second sentence is usually something gleaned from one of my hours-long interviews. I select this sentence based on how unique and universal each classmates’ truth is.

Tyler comforts his five-year-old daughter, Eisley, after awakening her from a nap at their home in Danville. Tyler works long hours at the Thyssen Krupp factory, where he makes camshafts for cars. He aspires to be a gym teacher and basketball coach.

JTD: Your choice of camera – a point and shoot film camera, which you prefer for its “nonchalance” – seems to be to be the perfect tool for this body of work. The aesthetic you employ, while deceptively simple in some ways, is quite hard to use effectively. Why did you choose this particular camera and method of working? Do you feel that using more simple or understated equipment allows for a greater authenticity than you could achieve with other camera equipment? Or is there another reason altogether?

SS: Yes, simple equipment allows for greater authenticity. My least favorite part of photography has always been the camera itself. The year after leaving behind a pool Canon 1DX at the paper, I shot exclusively on my iPhone 6 because it made connecting with people much easier. The point-and-shoot film camera eliminates the most technical aspects of photography. There’s no fiddling with shutter speed or aperture. You can’t review your photos. All that matters is the subject, the moment, and how the photographer frames the two.

People my age see my camera and say, “My mom/dad/grandma had one of those when I was growing up.” Photographing my classmates with the kind of camera they were potentially photographed with in fifth-grade might seem intentional, but really it’s just a lovely coincidence.

Brian, photographed one week after quitting his job at the Thyssen Krupp factory and breaking up with his girlfriend, nurses a whisky and energy drink at Dale’s Place in Danville. Brian said he has struggled alcohol since high school and that his time in the Navy exacerbated the problem.

JTD: To what extent are your subjects involved in the making of the work? Are they excited to be a part of it? What reactions have they had to the photographs?

SS: Portraits are discussed before, during, and after the shoot. I do this because it’s easy to get caught up in the photo aesthetics over representation. These people are my friends and I want them to be at peace with how they’re represented in this series. For example, when I photographed Brian last January at the bar, I first photographed him sitting in window light, framed by these gorgeous red slot machines. When I asked him how he felt about it he said, “It’s fine but I don’t gamble.” And he was right.

So we reconsidered the aesthetics for a more accurate photo, which was of him sitting alone in the dark bar. He’s a little out of focus, and I’ve been told the image is “too depressing,” but he and I agree that it’s real. In an effort to remain transparent with my classmates, I post an outtake or archival image from the project every Friday in our “MATS Kids” Facebook group. Reactions have been positive. A lot of my classmates are excited. Some have thanked me for listening. All are intelligent and engaged with the process.

Kelsey snuggles up with her boyfriend, Aaron, during a Super Bowl party at their apartment complex in Indianapolis. The couple has dated for nearly three years. Kelsey works in college admissions and Aaron in commercial real estate.

JTD: On your website, you write that the primary theme in your work is “dreams — the ones we chase and the ones deferred.” This is obviously a difficult thing to photograph, but you have done it quite well in The MATS Project. I imagine most viewers can relate to the disconnect between the aspirations of these individuals when they were young and the reality of their current situations. What is your ultimate hope for this work? What do you hope it communicates to the viewer?

SS: For the past year, I’ve had this quote from photographer Donovan Wylie on my desktop: “Accept that your work is more about you than what you represent, try to bridge that balance... try to translate personal experience into a collective one.” My work these days is about dreams because I’m so obsessed with chasing my dream of being a full-time documentary photographer.

So, asking people who are the exact same age as me, who were raised in the same town as me, who are experiencing the exact same moment with me, how their dreams will or will not manifest is a one way to translate my personal experience into a more collective one.

Nick walks to work at a renewable energy firm in San Francisco. He moved to San Francisco after living in Chicago for two years post-college. “Living in San Francisco is another world from Danville. I wouldn’t change growing up there for anything.”

JTD: You are currently based between Los Angeles, CA and Danville, IL, two very different places. To what extent does your location effect the work you make? Do you find that any code switching is necessary to go between the two very different cities?

SS: Danville and Los Angeles are quite different, but they are both home. And home is where you can be yourself. My process does not change from place to place. I am mostly interested in people, however, and the way people react to the camera very much differs from place to place. People in Los Angeles are very aware of the camera’s function. They have a hard time pretending I’m not there. People in Danville are curious, but allow for the camera’s presence to really disappear after a while.

JTD: Lastly, what are you currently working on? What is on the horizon for you as an artist?

SS: I’m headed back to Danville in August and September to try and finish up The MATS Project. Several of my classmates have updated me on upcoming major life changes, and I want to be there for those. I hope one day this project is published as a book. I hope one day it’s exhibited in both Danville and Los Angeles. For now, I’m documenting the life of a 70-year-old woman with a 25-year old spirit. The work explores what it means to age alone in Los Angeles.

JTD: I look forward to seeing both the book and exhibition of The MATS Project and also to seeing the new work. Thanks so much for taking the time to speak with me, Sunny.

SS: Thank you for such thoughtful questions. It’s been my pleasure.

Some members of my fifth-grade class on a field trip photographed in 2003 at Kennekuk County Park in Danville, Ill.