Q&A: serrah russell

By Zora J Murff | Published on April 24, 2017

Serrah Russell holds a BFA in Photography from the University of Washington and currently makes her work and her home in Seattle.

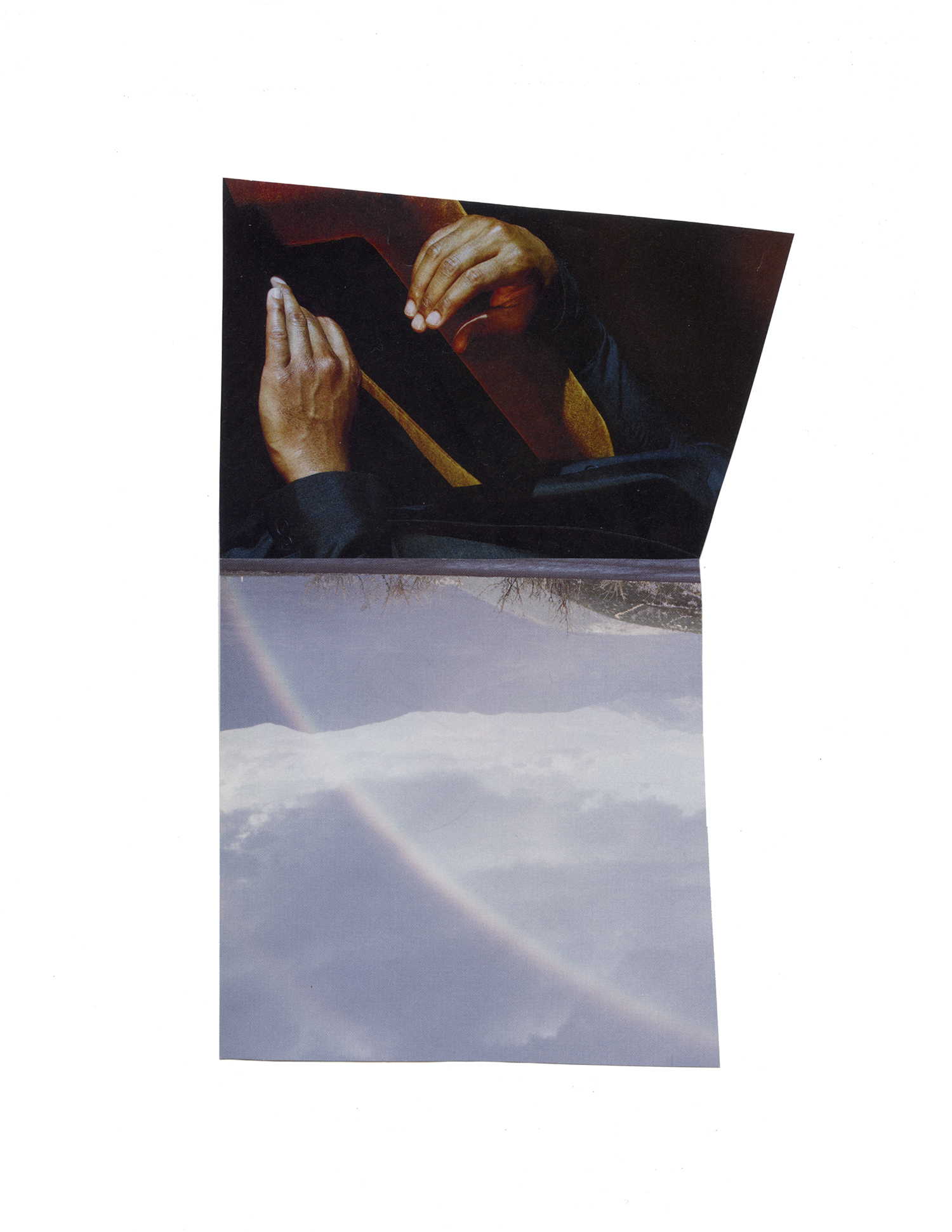

Her practice is a constant exploration of the photographic image and its ability to evoke memory, emotion and association. Using instant film, digital photography, and pre-existing photographic material, Russell creates works of collage, sculpture and video that alter the original intention of the source material by shifting focus away from the intended subject and onto the portions of the image that drift into the periphery. Russell harnesses the malleability of the photographic image to investigate the relationship between subject and surrounding and the human emotions that are visualized within one's physical environment. In her work she seeks to encourage empathy, to evoke the feeling of being in the right place at the right time, to recall the déjà vu of a dream.

Russell's work has been exhibited in numerous solo and group exhibitions in the Northwest, including at Glass Box, Two Shelves, SOIL, Photo Center Northwest the Alice, the Hedreen, Frye Art Museum, Lawrimore Project and has also exhibited in Vancouver, British Columbia; Melbourne, Australia; London, England; Athens, Greece, and New York, NY.

Zora J Murff: Hi Serrah, thanks for taking part in this interview. Let's begin by getting to know you a bit.

Serrah Russell: I grew up here in the Pacific Northwest, specifically in a suburb about 30 minutes outside of Seattle. I enjoyed writing bad poetry and taking emo photos in high school, so naturally I decided that I wanted to major in Photography. I went to the University of Washington, where I received my Bachelor of Fine Arts in Photography and pretty soon after graduating, I co-founded the online art platform, Violet Strays, as a way to connect with the Seattle arts community. By curating temporary exhibitions on the internet with local and international artists, it led me to get to know a lot of people and to find ways to exhibit my own work as well. I've been living and working in Seattle, simultaneously making art and enabling art.

ZJM: Can you talk about your creative process in general as well as how your use of photography and collage overlap?

SR: When I first began studying art in collage, I often would take the assignments very seriously and plan out exactly what I wanted the work to look like. Eventually I began to trust my instinct a bit more and to let my feeling guide me to a place that I hadn't practiced at the beginning of making. I think that point of trusting my instinct happened when I studied in Rome. When I was there, everything I took photos of felt incredible, because it's Rome, but also felt super touristy and cliché, so I just couldn't tell if what I was making had any meaning.

That struggle, paired with finding some incredible vintage Italian fashion magazines, led to me using collage as a medium. I felt that with collage, I was able to be flexible with the work – I was able to use photography but manipulate and construct it into something that felt true and honest for me. Collage felt like a quotation, using the words of someone else, removing it from the original context and placing it into your new place, giving it a new voice.

So for me, collage and photography aren't too far from each other. I see my works of photography as typically collage-like, and I see my collage as coming from a photographic background and context. I do tend to vacillate between the two. For instance, I just completed 100 Days of Collage, and since I completed that in March, I have not made another collage and have been focusing on my more appropriative Polaroid work, and working on a series of digital photography.

ZJM: Where does your inspiration come from?

SR: I always want to ask that question of others, but I have a hard time pinning it down for myself. I can say that I find a lot of inspiration in text rather than image. I have taken to keeping notes in my journal and on my phone, sometimes by texting myself, of portions of lyrics that I hear when I'm driving, of something I read on the internet, or hear on a podcast. I am inspired by my own memories, by the objects, places, scents, and tastes that stay with me, even if the story of the context has been erased. Sometimes I'll have a dream that will lead into a piece or a work. Also, recently, I have been running a lot more, and often in that meditative state of simply trying to get through another mile or get up the hill, I take my mind to another place and find that I can visualize ideas a lot more clearly than I can simply sitting in my studio.

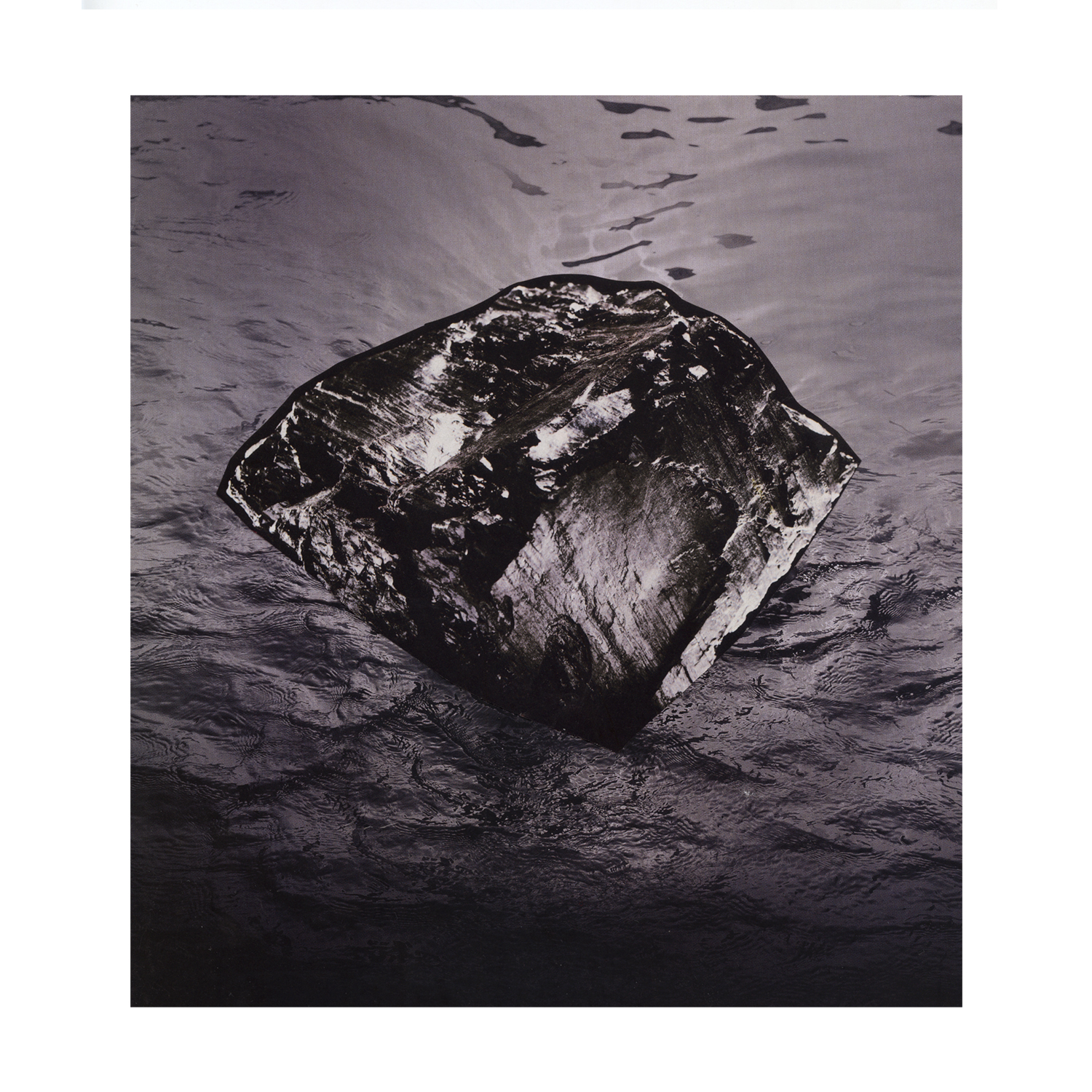

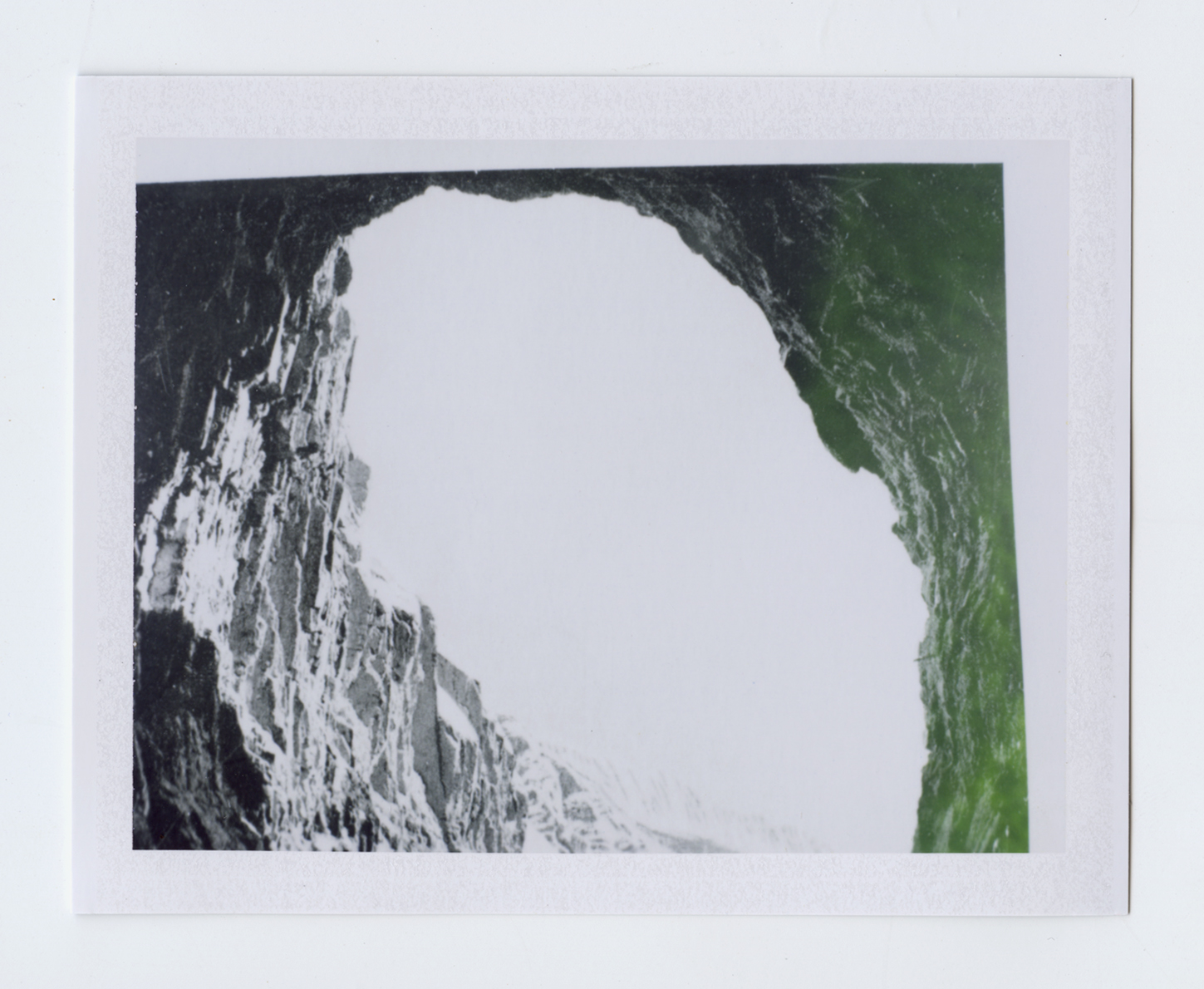

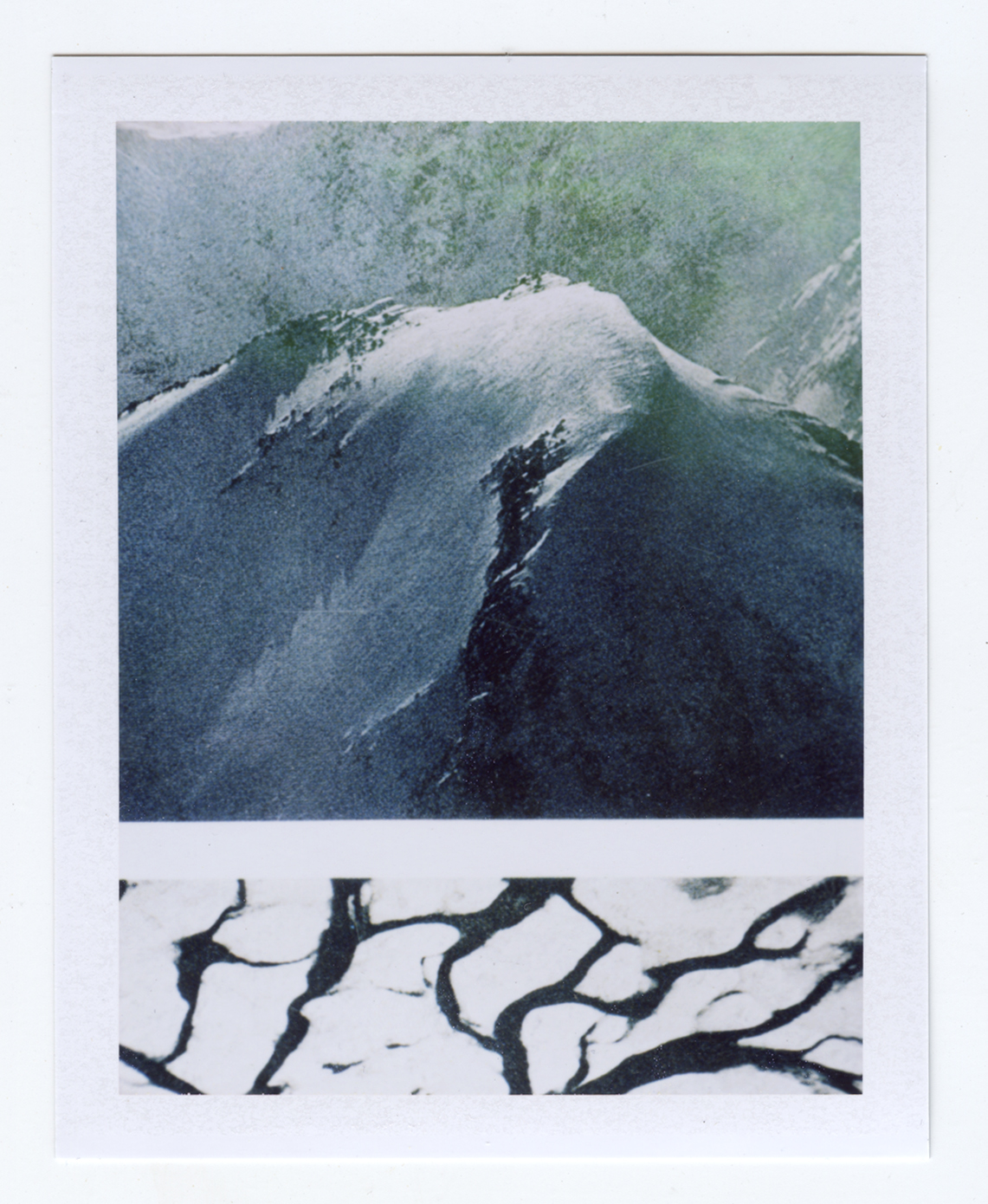

ZJM: Let's talk about your series When we are, when are we?

SR: It was a body of work that is somewhat ongoing. It consists of National Geographic magazine images that are rephotographed using a Polaroid Day Lab. The Day Lab has a glass clear surface that is about the size of a standard Polaroid, and whatever you place on that surface can be reproduced into a Polaroid. It is an act of collage, but only through the use of removal or subtraction rather than addition. I end up editing out most of the context and you're left without the place or the time, but more of a gesture of a body within the landscape, a curve of a swan, a horizontal line, a crack of a tree – and I'm interested in the way it allows me to focus in on the core of who we are, no matter where we are, when we are.

ZJM: There are a few aspects of this series that bring about existential questions for me. But I feel that I was most drawn to your use of landscape photography with minimal human presence. How do you think this adds to the work?

SR: I am always drawn to who we are and how our surroundings influence who we are, how we feel, what we become. I don't know if this is a specifically female interest, but I was very influenced recently by Rebecca Solnit's book, As Eve Said To The Serpent: On Landscape, Gender, Art, and her writings about women placing themselves in the natural environment, becoming part of it, and always removed from it. You'll see in most of my collages a merging of the body with the landscape, forcing a perspective where the two become one. I like the openness and abstractness of only including just a bit of the human figure so we can all imagine ourselves within the image.

ZJM: Removal of context, images, existentialism, and the environment also makes me think about our current precarious political situation, and all of the talk of 'alternative facts'. Do you think your work contributes to this dialogue?

SR: I haven't thought of it as having a political point of view, but aren't all works of art a political act? I certainly don't want to erase the facts or the specificities of our past, I think we need to remember those even more now, to keep ourselves from repeating, as they say. But I do think that much of my work is an attempt to change our way of seeing, to bring about a form of empathy. What if everything isn't how it has seemed? Or what if we can place ourselves within another time, another place, and see the humanity, the reality there too. I think the act of looking beyond, and looking behind can help.

ZJM: I like that sentiment about placing ourselves within another time. It reminds me of a James Baldwin quote from Stranger In The Village, "People are trapped in history, and history is trapped in them." The past is inescapable, and maybe it is through looking at the past that can help us see ourselves more clearly.

SR: Oh, I love that. That's beautiful. Along with that, that makes me think about how I view landscape and even domestic objects that surround us, as containing within them the history and emotions of the past, of what happened there years before. A quote I love that says this more eloquently than I ever will, but that feels consistently relevant to the work I make in regard to memory and landscape is this one by Rebecca Solnit from A Field Guid to Getting Lost:

"Perhaps it's that you can't go back in time, but you can return to the scenes of love, of a crime, of happiness and of fatal decision; the places are what remain, are what you can possess, are what is immortal. They become the tangible landscape of memory, the places that made you and in some ways you too become them. They are what you can possess and what in the end possesses you.

The places in which any significant event occurred become embedded with some of that emotion, and so to recover the emotion and sometimes to revisit the place uncovers the emotion. Every love has its landscape. Thus place, which is always spoken of as though it only counts when you're present possesses you in its absence, takes on another life as a sense of place, a summoning of the imagination with all the atmospheric effect and association of a powerful emotion. The places inside matter as much as the ones outside."

ZJM: Going back to the idea of the human figure being present in the landscape, you recently started a new series, A Woman Is Always An Island. I like the use of water as a metaphor for emotional depth as well as the physical tension between floating and sinking. How does the body and water inform the series?

SR: I came upon the idea of this project while on a run near the water. I had recently completed a body of work called Islanded that dealt with distance and tension between two places. I was curious what happened in that liminal space. The work was about isolation and independence, about not knowing where you are or where you want to be and about the distance between. I was looking out across the water to an island, and I somehow made the connection of a woman being like an island. That she is both seen and unseen, strong and rising and yet, also fragile and close to disappearing or being erased. I loved the visual of a body floating in the water, hovering, what needs to take place to make that happen, and what that symbolizes in how one keeps afloat. I like that the body is both all we have and also we have no control of it. I like that the water recalls relaxation and cleansing and calm, and yet, also is very dangerous and our bodies can not survive within it. We desire it and yet are not meant for it.

The series began with an idea and a visual image, which rarely happens for me. I had a clear vision of what I wanted to create, what I wanted the series to look like and began to make that happen by asking friends to participate. However, what the series has become is much different. It has become deeper and richer for me because it has turned out to be less about the visual image, and more about the process. It has become a private performance and a ritual for two. The subject, the woman, jumping into the water, at all times of the year, into an open, natural body of water – something happens there. It is unique because it is not something that is typically done. It happens at sunrise, the woman stays in as long as she likes (or can stand based on the weather) and after she gets out, I jump in. I usually don't say in as long as the subject, but I want to always jump in, so that we have that shared experience, of sharing the same water, the same pleasure, or the same pain.

As I've spoken about this work to many more women, many ideas about water rituals have arose, both cultural, religious, and even self-created. I love that this project has grown in my way of understanding it through the women that participate, and I can only hope that I will be able to continue to make this work for years to come, including as many women as want to be part of it.

ZJM: This work seems like a departure from your collages in the fact that the figure becomes recognizable, but the body still merges with the landscape. Do you see these photographs as an extension of your collages? Something more? Something different entirely?

SR: You're right. Like I mentioned before, my photos are collage-like, and my collages are photo-like. And yet, for this work, I truly don't see it as collage. I see it as collaboration. I see it as a performance ultimately and the photo is part of it, to document, but the photo wouldn't be meaningful as just a solitary photo. I feel that the photos have meaning because of the process. It is still connected to my work in the aspect of body and landscape. I suppose I'm making the collage in real life. When I collage, I would try to tell this same story by merging found imagery, here I try to document what I am seeing in real time of the body responding to the landscape and environment around it.

ZJM: What's next for you, Serrah?

SR: Well, I've begun working on plans for a large-scale publication of my entire 100 Days of Collage series, so that's exciting. Also, in just a few days I have a brand new body of work opening up at Gallery CLU in Los Angeles in the show Future Potential of Dreams along with artists Megumi Shauna Arai and Yael Nov. The work continues using the Polaroid Day Lab machine and this time using source material from slides from a family collection from before I was born and National Geographic magazines from before I could remember. I scan those polaroids and continue to manipulate them digitally. The opening is April 29th, 5:00pm-8:00pm, and if anyone reading this is an LA, please come out and see it, I'd love to meet you.

All images © Serrah Russell