Q&A: Meghann Riepenhoff

Meghann Riepenhoff in conversation with Allie Haeusslein, Associate Director, Pier 24, on October 20, 2015. This conversation was originally published in the catalog for Riepenhoff's Littoral Drift exhibition at SF Camerawork. Published on Strange Fire Collective on March 10, 2016

Born in Atlanta, GA, Meghann Riepenhoff is an artist based in Bainbridge Island, WA and San Francisco, CA. Her work has been exhibited internationally and nationally at venues like the High Museum of Art (Atlanta, GA), Galerie du Monde (Hong Kong), San Francisco Camerawork (San Francisco, CA), Higher Pictures (New York, NY), Foley Gallery (New York, NY), Duncan Miller Gallery (Los Angeles, CA), San Francisco Arts Commission Gallery (San Francisco, CA), Photographic Center Northwest (Seattle, WA), Memphis College of Art (Memphis, TN), and the Center for Fine Art Photography (Ft. Collins, CO).

Riepenhoff’s awards include a Fleishhacker Foundation grant, being named a Critical Mass Top 50 Photographer, Honorable Mention for the John Clarence Laughlin Award and exhibitions by Charlotte Cotton and Karen Irvine. She was an artist-in-residence at the Banff Centre for the Arts (Alberta, CAN), Rayko (San Francisco, CA) and an Affiliate Artist at the Headlands Center for the Arts (Sausalito, CA).

She has been published in Harper’s Magazine, Aperture PhotoBook Review, BOMB Magazine Word Choice, B&W and Color, The New York Times, the San Francisco Chronicle and The Seattle Times. Her work is in collections at the High Museum of Art, Museum of Fine Arts Houston, and Worcester Museum of Art. She received a BFA in Photography from the University of Georgia and an MFA from San Francisco Art Institute, where she is a member of the visiting faculty.

Allie Haeusslein: What was the origin of this most recent body of work, Littoral Drift?

Meghann Riepenhoff: I was working at the Headlands Center for the Arts, watching the landscape change around me. With my studio perched on the continent’s edge, I was looking at the shore, and thinking about that border of our terrestrial lives and the aquatic abyss, the meeting place of two environments and where they tangle.

I had a plan to make photos of bioluminescent jellyfish, so I constructed boxes to hold color photo paper that I could take into the ocean at night. Unfortunately, my experiment was during the wrong lunar cycle. I found myself with materials and time but no bioluminescence, so I began submerging the paper to see what kinds of results I would get. The first pictures I made in this way were visually exciting—they looked like the landscape I was working in. Anna Atkins, 19th c. botanist and photographer, made cyanotype photograms of seaweed, algae, and other specimen from the shoreline. It seemed perfect to bring the cyanotype back to the beach—back to the ocean, and to work with it in a new way.

Reflecting back, it strikes me that failure is a recurrent theme in my work. When we let go and allow things to fall apart, there’s the potential for something amazing to emerge. This idea inspired me then, and continues to be a philosophy that has driven me forward ever since.

AH: You describe littoral drift as a very existential idea—the edge of where we can exist. How is it defined in ecological terms?

MR: Littoral drift is the action of wind-driven waves moving sand and sediment along a shoreline. It’s a geologic term, and so it evokes time and processes that are beyond our control, beyond our lifetime. I think it speaks to forces that are larger and more powerful. And, I liked the play on words. Littoral sounds like literal, and these pieces are literally drifting in form as things change in them over time.

AH: Thinking about how you’re physically making these works, can you walk us through the process of preparing the photographic surface in the studio before you venture into the landscape?

MR: Cyanotype is made up of two discrete chemical parts, solutions that become sensitive to UV light when combined. First, I pre-coat the paper with the solutions on both sides, brushing the emulsion on like watercolor. Then, I allow the pieces of paper to dry, and box them up to be taken out in the landscape, where they are activated by UV light.

Occasionally, I experiment with variations in this basic process. For example, I sometimes submerge half of a piece of paper into part A, allow that to dry, and then flip the paper over and submerge the other half into part B. Where the chemicals align, they create a kind of an artificial horizon.

AH: Once you get this paper out into the landscape, the process seems very performative, one that intimately involves your hand, and even your body to an extent. Can you describe how you engage the elements in the landscape with the paper?

MR: Initially, I evaluate where the print will have contact with water and the nature of this contact—submersion, floating, etcetera. Then, I decide whether or not to engage other elements from the landscape. For example, do I bury part of the print? Do I place rocks on top of it? Drape it over a tree? Once this process of exposure and development is underway, I watch and re-photograph the print while it exposes for about four hours—depending on the weather and the nature of the print’s contact with water. It takes roughly forty-eight hours for the that blue color we associate with cyanotype, the Prussian blue pigment, to present itself in the print.

Documentation of works in progress in the landscape

AH: I find it fascinating how your process and work are so intricately linked to both science and to a lot of unpredictable elements—you can’t control the wind or water or Earth. So I’m wondering how much control is involved in the final image? Are the results more deliberate or serendipitous?

MR: I affectionately call it chaos with a dash of control. The work requires letting the landscape—which is, in some ways, my collaborator—be the driving force. Some days this is easier than others. In more quiet environments it can feel meditative. There’s a place I like to print, Hilton Head Island in South Carolina, where the water is gentle and I can make work in the tidal pools. But then in the Pacific Ocean—water I’ve found to be wilder than any other, I have to spend a lot of time evaluating the shoreline, waves, and wind movement to see where I’m even physically capable of making a print.

AH: You mentioned before how, in some cases, you even bury the paper in the sand. I noticed in one image documenting your working process that you even sprinkle sand and various sediments onto the paper. Can you talk a little bit about the significance of this additive process and why it’s important to you that these works bear physical traces of the landscape itself?

MR: We traditionally think of photography as a subtractive medium that takes excerpts from the surrounding world, whereas painting is more additive. Maybe part of the reason I’m adding things to the print, like pouring additional water on or throwing sand at it, is to upset that expectation. The works both hold and shed debris from the landscape, which functions as residue of the physical inscription from each place.

Documentation of works in progress in the landscape

AH: For me, there is definitely a painterly aspect to the work, and you play with that divide between mediums. As a viewer, it’s not always immediately clear what you’re looking at, that it is, in fact, a photograph. In thinking about the material itself, I know that cyanotypes tend to be relatively stable when compared to other historical materials. But you end up leaving them partially processed, and as a result, they are subject to changes based on the environment over time. Can you talk more about that?

MR: I am interested in the transformative nature of repositioning materials--asking them to behave differently than they’re supposed to. The pieces do not stop changing when I bring them from the beach to the studio. The Prussian blue pigment remains sensitive to UV light because I’m not washing out the residual chemistry, so the making continues for as long as the work exists.

When I first started making this work, I went to conservators and cyanotype experts to ask them what we might see in 100 years. The answer is: we don’t fully know. I’m really excited by this uncertainty because, much like life itself, change occurs in ways we cannot predict.

AH: It feels to me that the material and its impermanence is very much connected to how you’re thinking about the content and how you’re thinking about the overarching process.

MR: The driving force behind this work was an investigation into impermanence, which is really the driving force of our lives—our own dynamic existence. I tend to gravitate towards landscape, photography, and the human condition as ways to examine change.

Earlier, I mentioned witnessing littoral drift in the landscape from the Headlands Center for the Arts. I was thinking a lot about photography too as an ever-evolving medium that’s constantly reshaping itself in the face of technological developments and practitioners’ investigations.

I was also thinking about how Stephen Shore defines an image as an object that has it’s own life in the world, to be “saved in a shoebox or in a museum.” At the crux of that idea is the understanding that photographs change according to context, viewership, time, etcetera. I wanted to make work that changes too—that pushes back against this idea of the static image. I also wanted to push back against the idea of the archival image, something that seems to imply that photography is exempt from the very nature of life itself, which is change and, ultimately, death. People often ask me what the work’s final state is after I’ve told them it changes. The final state is change.

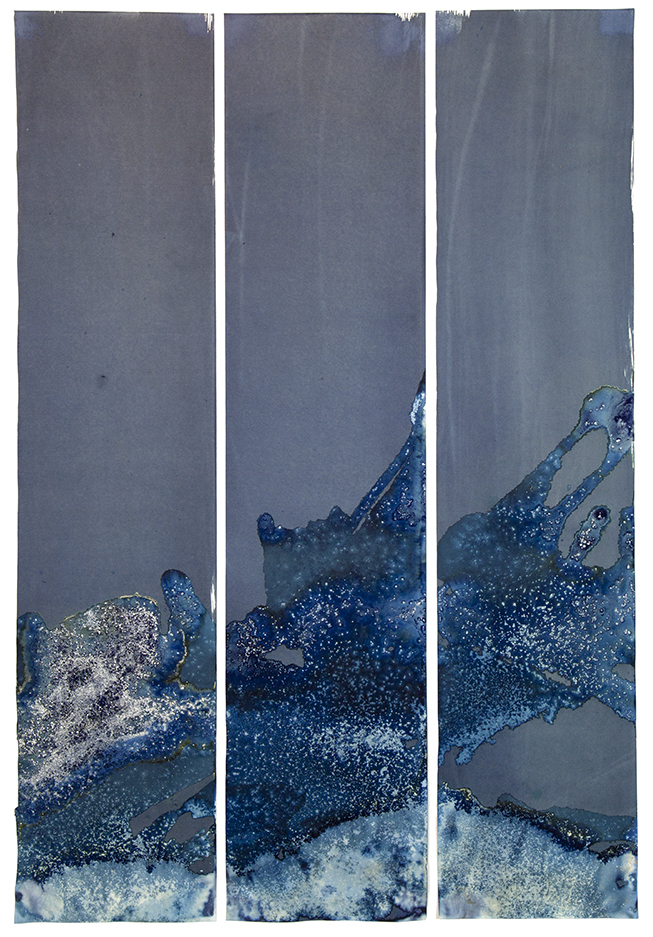

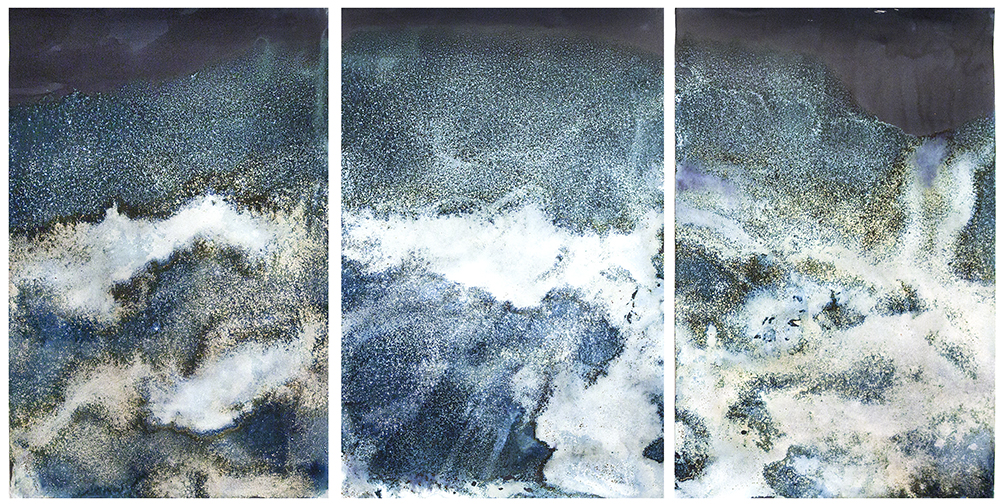

© Meghann Riepenhoff, from Littoral Drift

You’re not only challenging the way we traditionally understand photography, but also how we think of a photographer’s working process. As you create one-of-a-kind images, I imagine your editing process is very different from someone like Henry Wessel. How do you edit this work and determine what feels like a successful image?

It is difficult to select images, and also to think about how they’ll live in an exhibition space. As for determining which images work, I talked to photographer Linda Connor about this years ago, asking her what makes a successful photographic composition--a ridiculous question! She answered that an image should have a sort of electric charge to it. I think that’s what I’m looking for: this intangible way that an image actively impacts you.

Earlier, we were talking about the work’s relationship to painting. And for me, especially with the larger work, my first point of connection was not to the photographic, but rather to artists like Mark Rothko or Yves Klein. How did you envision viewers encountering this work? Were there sources of inspiration outside of photography that guided your thought-process?

I love the way you describe approaching my work, and your method of experiencing it—not just seeing it—is what I hope for. In reference to James Turrell’s work, I read a piece by Atsushi Sugita that described light as having an existence to which we are intuitively connected. Light is something that is not well known, yet frequently encountered. He also described Turrell’s blue as a solid blue, but a color that is empty at the same time—a color that is material and immaterial. Thinking about how we experience light in this way was really exciting to me because it describes seeing as something that happens with your whole being.

With photographs at a certain scale, there is an exquisite level of detail. You can stand back from one of these pieces and feel like the wave is about to crash over you. Or you can come in really close and see where the wind pulled the chemistry over and around individual grains of sand. So there is something about the infinitesimal and the immense that’s happening simultaneously here, and the viewer is positioned in the midst of that meeting point.

The way you describe this kind of encounter, along with your interest in materiality and immateriality, brings to mind the idea of the sublime. Especially the sublime as it relates to the awe-inspiring landscape from nineteenth century art history. I suspect that was something you were thinking about when making this work. Can you speak about this?

I think artwork, like being in a classically sublime landscape, can elicit the experience of transcendence. I wanted to work in the sublime landscape, not attempt to recreate the sublime in a studio. I integrate the massiveness of the ocean and the wildness of the landscape into the actual production of the work, and then imagine how these enigmatic forces that exist around us will shape the work over time.

How we try to image the sublime is fascinating, especially when you consider that we’re a snapshot of it. In fact, some sublime force generated us—we are pieces of it, like Carl Sagan’s statement that we are star stuff.

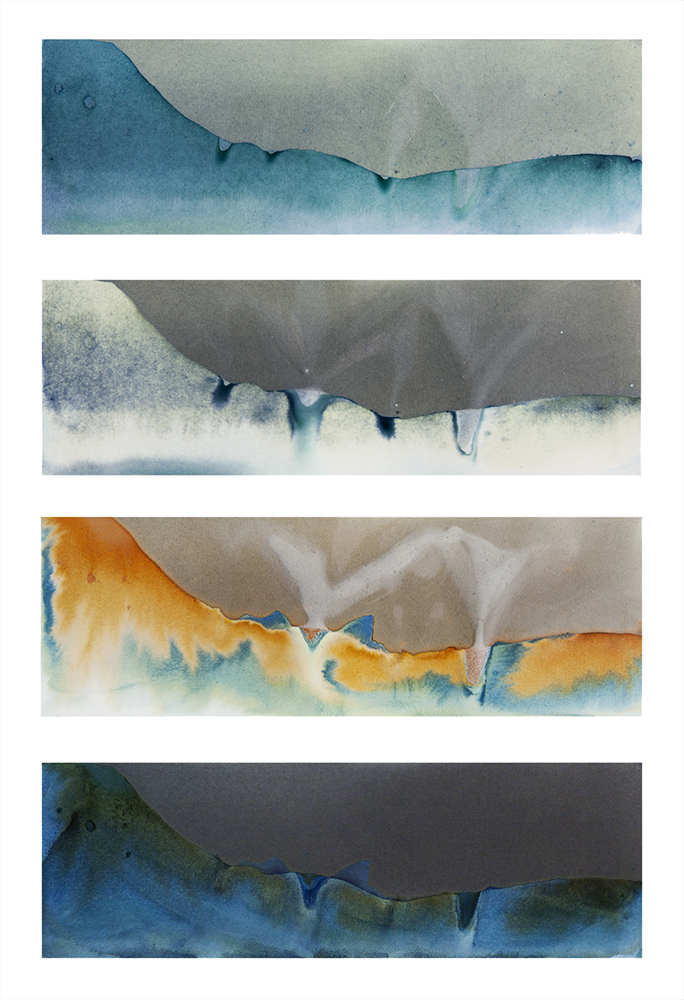

So we touched on something earlier— this other facet of the Littoral Drift project— which I wanted to delve into in greater depth. With the Continua, you re-photograph a single cyanotype or a detail of a cyanotype over time, looking at how it shifts and evolves. What inspired that additional facet of the project?

I saw that the pieces may not reveal their changing nature in the timeframe in which they are often encountered. I wanted an interesting way to address this, one that wasn’t so far off from the actual thing itself. I re-photograph each work as it processes, develops, and exposes out in the landscape and then, once again, when I bring it home. The Continua pieces demonstrate the changing nature of the work in a way that is less evident when you’re encountering the work briefly.

I understand you’re spending a lot of time working in Washington State after working in the Bay Area for some time. Has working in a new place shifted how you’re making pictures or thinking about the project?

My studio is close to the Puget Sound, which has such gentle water compared to California beaches. So I’ve been able to image subtler water behaviors like tidal shifts, which look almost like tree rings. I can see things in a new way because the water isn’t so tumultuous and churning.

I’m always responding to the environment around me. Being in western Washington I’m making a lot more rain prints and have become much more familiar with a variety of precipitation. I’m also becoming keenly aware of ferry waves because this region relies heavily on boats. I picked out a spot on one beach where I like to print, and I know that seven minutes after the boat passes this one point in front of me, the waves will hit the shore with some vigor. And so I’ve made prints that are recording that.

That’s so interesting. Being in that location has not only made you privy to certain distinctive environmental phenomenon, but also to the role that humanmade forces can play in your work.

I am fascinated with how humans identify with the environment, and how we so often try to function like we’re separate from it. But we are fundamentally integrated, and I like recording a mix of human and non-human forces.

With this work, I’ve always been moving from place to place. The work comes with me wherever I go. Instead of bringing the traditional camera and a roll of film, I bring cyanotype-coated paper, in case I run into water that interests me. I am inspired by the range of terrain I encounter and how I respond to each place. It can be disorienting to regularly change the location where I work, but in the most exciting kind of way. Each place just begs for me to try something new.

Above: Works from Littoral Drift // © Meghann Riepenhoff

© Meghann Riepenhoff, Continua

Littoral Drift at SF Camerawork