Q&A: gay block

By Jess T. Dugan | November 1, 2018

Gay Block began photographing in 1973, making portraits of her mother and their affluent Jewish community in Houston. Her landmark work with writer Malka Drucker, RESCUERS: Portraits of Moral Courage in the Holocaust, Holmes & Meier, 1992, is now in its 5th printing. The portraits were exhibited internationally at over fifty venues, including Museum of Modern Art, NY, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and The Corcoran Gallery in Washington, DC. Block’s visual autobiography of her mother, Bertha Alyce: Mother exPosed, UNM Press, 2003, contains an award-winning 24-minute video seen in over 25 film festivals. In 2006, Block completed a re-photographic project of the women photographed as camp girls in 1981, producing a series of black and white/color diptychs, and a film. Radius Books published a 2011 monograph of Block’s work: About Love: Photographs and Films 1973-2011, which contains over 200 images and 5 films on DVD. Block’s photographs are collected by museums and private collections throughout the world including MoMA, NY; SFMoMA; and The Museum of Fine Arts Houston.

Jess T. Dugan: Hello Gay! Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me. Although I realize you have had a very long and wonderful career, I’m still interested in revisiting the beginning. What originally drew you to photography, and how did you end up pursuing a life and career as a fine art photographer?

Gay Block: In 1971, I was twenty-nine, had been married for ten years, was the mother of two children, and seriously felt the need to do something more, so I enrolled in architecture school at the University of Houston. In my second year I took a photography course and knew I’d found what I loved.

JTD: You have written that you learned about love through photography, which I think is such a beautiful idea. Can you elaborate on this a bit? How does this manifest in your work?

GB: In 1973, now enrolled in art school, my first photography teacher assigned us to load cameras with tri-x film and shoot something we needed to understand. I found myself the next morning in my mother’s bedroom where she was standing nude, on the phone, bathwater running. This wasn’t an unusual sight – she’d always enjoyed being nude. As I waited for her to hang up I snapped a picture. No reaction. Then another. When she got off the phone she gladly started posing for me. Five negatives. I made a few prints, showed them to her and we laughed about them, but I hid the negatives, not dealing with them again until her death in 1991.

This was the beginning, however, of photographing her, making recordings of her, trying everything I could to get to know this woman whom hadn’t given me the love I wanted. Working on the book for ten years after her death began to make me aware that she’d given me the only love she knew. This work eventually became my second book, published in 2002, Bertha Alyce, Mother exPosed. I did this book in an attempt to redeem her – so many disliked my mother, almost as much as I did. Whether or not I redeemed her, I redeemed my own feelings about her and began to understand love in the only way it was possible to experience with her.

In 1982 I had my first solo museum show in Houston. As I walked into the gallery, Mother ran up to me. I expected her to say she liked my new pictures but instead she said, “How do you like my new necklace?” This became my favorite narcissistic-mother story.

Twelve years have passed. Mother has been dead for three years and I have all her jewelry. This piece stands out, different from all the rest. No diamonds – no stones at all. Recalling the last time I saw this necklace, I imagine the untold story:

You bought it especially for my opening, in my honor. You thought I would prefer it because it was designed by an artist, Agam. Right? Why couldn’t you tell me you did it for me? Or why couldn’t I know it without your telling me? Why do you have to be dead before I begin to forgive you?

In addition to Mother, I wanted to understand her community. I felt critical of their values, personally resentful that, in spite of our level of comfort, I had grown up seeing values I didn’t respect. I felt they’d sought the comfort of affluence, a heavy social calendar and letting their “maids” raise their children.

I began making appointments to photograph them and record interviews, and, much to my surprise, I discovered why they had taken these paths. Many had memories, or at least had heard from parents, of a time and place where no Jews had opportunities for upward mobility or religious freedom. I went into their homes with intolerance and came out with a portrait of someone I liked and understood. Even without the interviews I could see this openness in my portraits and knew that I wanted to keep making portraits for the rest of my life. Talking with people about their values and then photographing them exactly as they looked was deeply satisfying for me. I hadn’t known myself, hadn’t verbalized my own values, so that talking with them helped me know what kind of person I wanted to become.

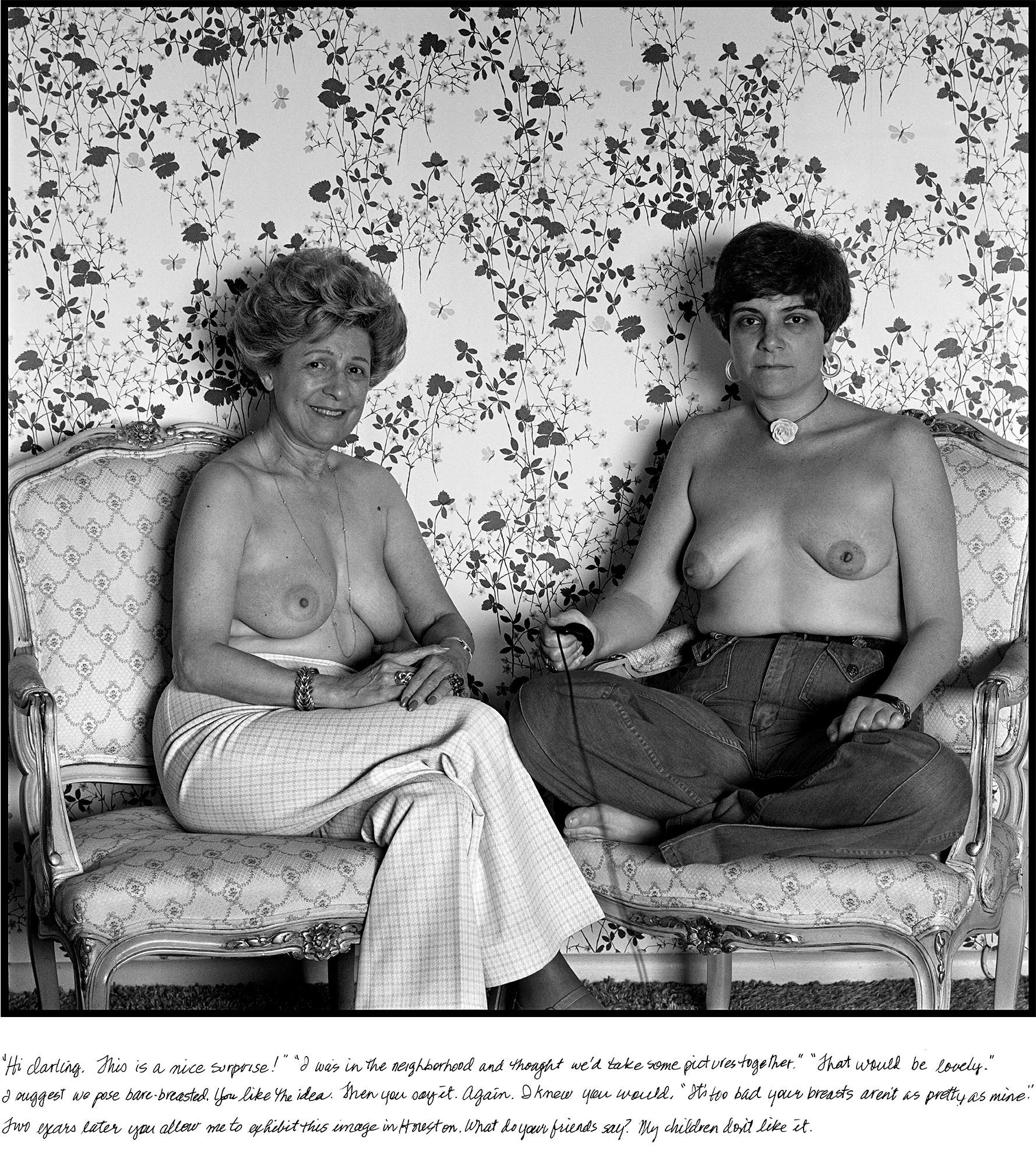

I was surprised that this mother/daughter pair were dressed almost identically when I went to the daughter’s home to photograph. During our interview, when they each took the same position, I asked them not to move, turned off the recorder, and shot this 4x5 image with my view camera.

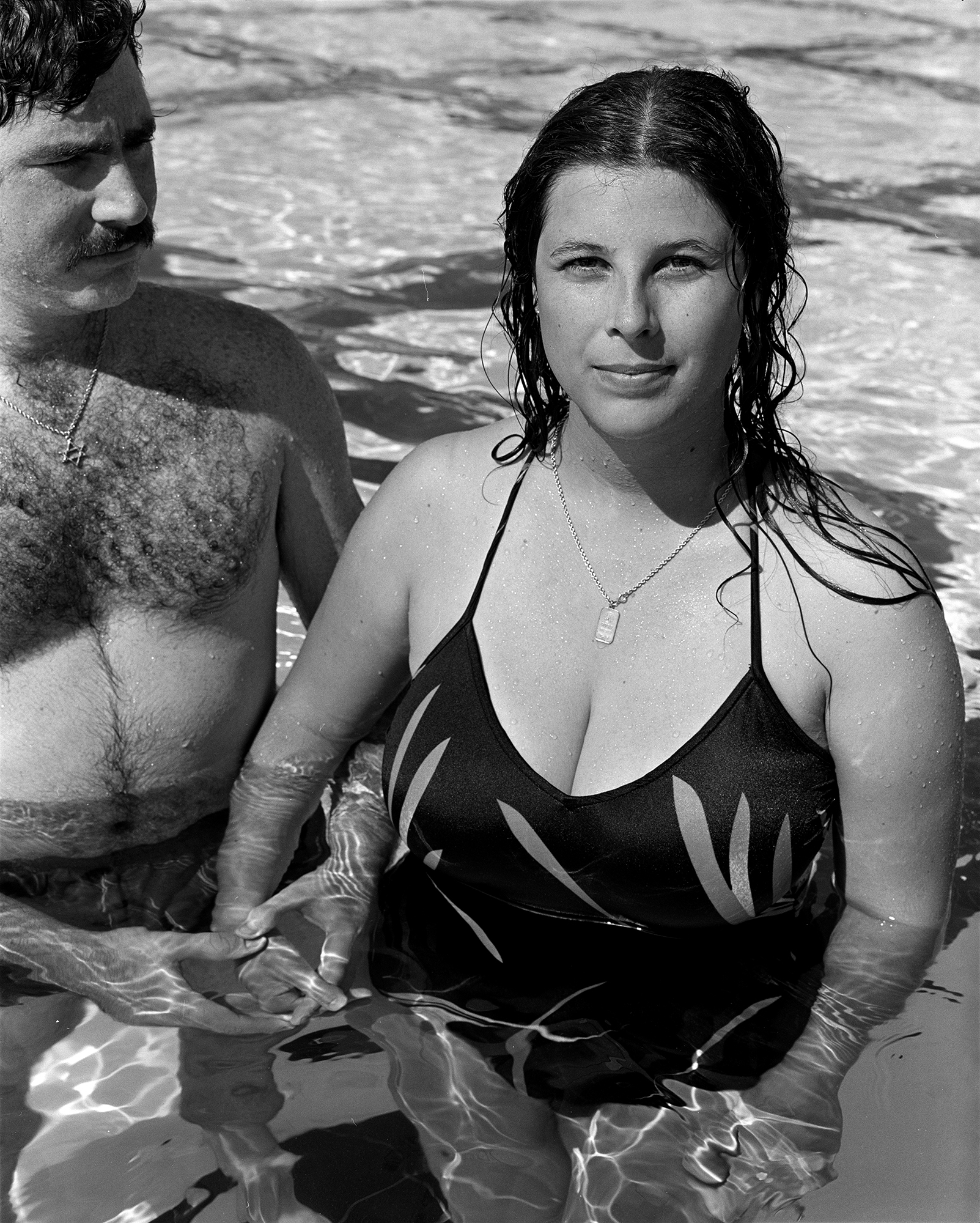

By 1981 I tired of making appointments and I started photographing at the Jewish Community Center swimming pool. In the fifties I had grown up going to the country club where we kids were dropped of while our parents played cards or golf. Later, as a young mother, I had a pool in the back yard where swimming was a family matter with a few friends invited over from time to time. But at the JCC I discovered an entirely different milieu: the parents were in the pool with the kids. Families were having fun with other families, children were watching them and I imagined they were learning how to make friends. As usual, I felt that finally I was seeing the “right” way to learn love and that all my life I had been doing it “wrong.” Week after week I went to the pool, getting to know the people and seeing how they gathered with their friends in separate sections. The Russian émigrés in one area, the teens in another; the dads with young kids were separated from the young couples. They were amused by my wanting to take their pictures and I had a great time. One day I saw an overweight woman standing in the middle of the pool holding hands with her husband. I motioned for them to come near the edge so we could talk. What had moved me was seeing the love in the eyes of her husband as he looked at her. Could an overweight woman actually be loveable? I had always been overweight, albeit less than she, and though I knew that my husband loved me, I had never felt loveable. Seeing this couple changed my whole outlook on what might be possible for me. I continued to photograph overweight girls and women, more and more seeing them as beautiful and loveable.

When I saw this baby on her dad’s lap like this, I rushed over and was sitting on the end of the chaise taking pictures before I finally looked up, laughed, and said I hoped it was okay!

Also in 1981 I photographed for a week at Camp Pinecliffe in Maine, where I was a camper in the 50s – and captain of the Blue Team! – and where my daughter at 15 was attending her last of 7 summers. I wanted to know what kind of values these girls had, what my daughter had been learning from her friends all those years. But when I got there and started photographing, I never asked the girls one question. All I wanted to do was photograph! I saw them as totally beautiful – all of them! I printed the images, had exhibits, but continued to need to know who they were. In 2006, 25 years later I decided to look for them – my daughter Alison did the research – and visited 65 of these women all over the country, asking, as usual, about their values, what was important to them. They were 33-40-year-olds. Telling you what I learned would make this very long indeed! I did do a 50-minute film about this work called Camp Girls.

One of my favorite projects was photographing, from 1982-85, the retired Jewish community of Miami’s South Beach. I loved these people for their independent spirit, their stories, their clothes, their gathering at the park by the beach for an afternoon Yiddish singing. I loved the way they argued and reminisced together. They were happy in Miami – they told me that in New York, they’d just be waiting to die but here they LIVED! I made many portraits and a film about them – I had to record them because I loved the way they talked almost as much as I loved what they looked like.

Zofia Baniecka, Poland, from Rescuers

Zofia smoked like this, lighting one cigarette from another, during the entire interview. She spoke Polish and was probably bored when our translator imparted her words to us. She was a committed and brave woman, hiding Jews in her flat as well as guns for the resistance, later being jailed several times as she always worked for a free Poland.

JTD: I am interested in your project Rescuers, for which you photographed non-Jewish Europeans who risked torture and death to save Jews during the Holocaust. You collaborated with writer Malka Drucker, who conducted interviews with your subjects to go alongside your portraits. How did this project begin and what motivated you to pursue it?

GB: In 1986, I met Malka Drucker and we began a relationship which would last over 25 years. That first year in Los Angeles she told me that her rabbi, Harold Schulweis, had asked her to write a book for children about the Christians who had risked their lives to save Jews. Malka had by that time authored several books for adolescents on Jewish subjects. When she mentioned this to me I asked if these people were still alive, because if they were, I would certainly like to meet and photograph them. I had been to Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Memorial in Jerusalem, and had walked along what is known as the Avenue of the Righteous, where carob trees are planted in honor of the more than 8,000 (at that time) Christians honored as Righteous Gentiles. I had assumed the names at the base of each tree was like a cemetery marker, that these heroes were no longer alive, but when Malka asked her rabbi he assured us that many are alive, some even living in L.A. Rabbi Schulweis had tried for over 25 years to bring these brave souls the attention they deserved, but so many who had survived without ever seeing a rescuer were worried it would whitewash the sacred memory of the Holocaust.

From our first interview we were hugely moved by their accounts of harrowing wartime experiences. Surprisingly, we were able to absorb them and still walk around in the world. In the beginning I was also dealing with technical decisions about whether to use color or black and white so I shot both. After the first 50 sessions I realized that only the color was working for me. I didn’t want these amazing people abstracted and removed from reality, which is what happened to them in the black and white prints. I wanted them to be as accessible as possible so that others could understand and relate to these almost UNREAL acts of courage.

We eventually traveled to Israel where over 30 were living with Jews they had rescued. Then we traveled to 5 countries in Europe, and through Canada and the USA where they were also scattered. After interviewing 105 of these people, Malka said to me, “It’s enough, Gay. We’re going to stop now and write the book!” I would have continued meeting these people forever – in fact, I’ve always been more interested in doing the photographing and meeting the people than having an exhibit. I knew, however, that we owed it to the rescuers to get their stories out into the world so others could know that it was ordinary people who had performed hugely extraordinary acts of courage. And of course, many had died trying to hide Jews.

Arnold Douwes and Seine Otten, The Netherlands, 1988, from Rescuers

We had a 3-hour interview with Arnold and Seine, best friends in and compatriots in their rescue efforts, in a Dutch village, Nieulande, that was ultimately honored as an entire village for all the Jews they rescued. I watched as Arnold recounted the stories with fiery passion, telling of how he was on the train every day to get Jews out of Amsterdam where they were in most danger. When he brought them to Nieulande he gave them to Seine, a school teacher with a wife and small child, who took them and then distributed them in the village, to be ready for the next Jews Arnold brought. They were very different and, although they were sitting next to each other, I could not photograph them together. The resultant images show the personality of each man more surely than I think any other images I’ve ever made.

I want to insert one account from Rescuers: Portraits of Moral Courage in the Holocaust. I choose this one because it is exemplar of the many facets of rescue – who did it, how, and how THEY survived after living through these horrors, forget about how WE survived hearing them.

We met Agnieszka Budna-Widerschal in Israel where she lived with her husband Shimon in a 4th-floor walk-up. Born in 1909 into a rare Polish Catholic family that was not anti-Semitic. During the war, she got a factory job with a German boss, met her Jewish husband, Motl, and got a big apartment so she could hide him and his family behind a false wall they built in the attic. Her brilliance was in making up stories on the spot to escape the Nazis and to avoid detection by nosy neighbors. Poland was the most dangerous country of all in which to rescue Jews because of rampant Polish anti-Semitism and yet she managed to save all six of them. Agnieszka had a daughter but sadly, Motl died in 1946. Agnieszka remarried another Jew, Shimon, but, she told us, “In 1954 there was another big wave of anti-Semitism. One day some older kids invited my daughter to walk home with them. They went by the train station and later the conductor told us he saw the older girls push Bella in front of an oncoming train. It was a catastrophe.” Agnieszka showed us a framed picture of Bella. “We came to Israel in 1958 and I was honored by Yad Vashem in 1982.”

So asking me how WE could walk out of such an interview, how could we even breathe after such a story, one of so many we heard, I can only answer with the question: How did SHE survive after that? And another question, how did I manage to take her picture immediately after such an interview? The answer might be that if she could do it, I could do it. I took the only picture of her that I could have taken – it was the way she sat during the entire interview. There was no other way to photograph her. A year later, another person I knew who was also working with rescuers visited Agnieszka, who said, “Just look at the awful picture she took of me!” When she handed Eva the 8x10 I had sent to her, Eva told me she was sitting in the same chair, in the same dress, in the same position!

Agnieszka Budna-Widerschal from Rescuers

JTD: Working on this project sounds both incredibly difficult as well as inspiring. How did making it affect you personally?

GB: You ask me how did the complexity, the fear, sadness, horror of these stories affect me? How did I keep going, doing two interviews every day with lunch – yes actually eating lunch – between the sessions? I can only answer by revealing that I seem to have an ability to absorb the pain of others without it crushing me. I do have empathy. I care deeply about people and am often engaged in helping to ease the pain of others. I am, however, capable of going on with life even after hearing, absorbing, and feeling others recount painful episodes in their lives. Perhaps it took time for me to absorb it, which may be the reason that, during the late 1980s, I made the decision not to show this work when I gave slide show lectures about my work. I thought of it as documentary work, different from my earlier portraits that were motivated by a more personal need to know and understand. HA! How little I knew! I finally realized that these people had taught me the most important lessons of all about values, that there’s no higher value than helping others. And even more, I realized that it was exactly who my father had been. He couldn’t stand to see others suffer. His entire life was focused on making the world a better place, and he’d done that with individual giving as well as tireless community work.

JTD: This year marks the 30th anniversary of the completion of Rescuers, which was originally exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1992 and subsequently toured as a traveling show to over 50 venues. Earlier this year, it was featured in the New York Times Lens Blog, which stated that, “in a time replete with misinformation and unsettling incidents of racial and religious violence, Ms. Block hopes to bring the exhibit back for the 21st century. She says these stories can inspire others to stand strong in difficult times.” Can you elaborate on this idea? What made you want to revisit this series now? What are your hopes for it in today’s current political climate?

GB: When Rescuers was published in 1992, we sent a book to each of the ones we interviewed, and over the years we would sadly receive death notices. Each one confronted us with feelings of loss – even though we’d met with them for only three hours, we felt we’d lost a best friend. It was astounding how strong our connection was to each one of these people, and that even today I can recount the details of every story when I see one of their images.

Rescuers became a solo exhibit at New York’s MoMA, thanks to Susan Kismaric and John Szarkowski. The galleries were always crowded, we sold many books, and then a larger exhibit traveled to over 50 venues. My favorites were the University galleries because the kids there knew little about Holocaust, and certainly nothing about rescuers. Malka and I gave many talks to students, telling them that what we’d discovered was that there were four parts to play if you were living in Europe during that time. You might be a victim (Jew, queer, gypsy), you might be a perpetrator (Nazi or Nazi collaborator in other countries), you might be a rescuer, and you might be a bystander. Those were your only four roles to choose from, and many had no choice. Most people chose to be bystanders. Few had the courage or the non-conforming personality of the rescuer. But then we asked students to consider what roles they play. Most of us play a combination of these roles every day, and we told them that being a rescuer today wouldn’t require risking their lives as it did during those years. They could stand up for someone being teased, they could resist homophobia, they could resist when they saw their friends abusing people with different skin color, or different eyes or ways of talking. We assured them that every day they might find ways in which to be rescuers.

Today, almost 30 years later, we are having a frightening resurgence of hatred of the other. As I write this, just yesterday 11 Jews were murdered during Shabbat morning services in Pittsburgh. This is horrifyingly frightening to me, to all of us. Our world today needs the example of the rescuers’ fearless resistance to that hatred. A recent survey revealed that less than 50% of Americans know the word Holocaust, evidence of our weakening education system. Kids are taught SO little about the history of the world that they might not understand the ways in which our current government is leading us down a dangerous path that the world has experienced before. Unfortunately, we fear history repeating itself and that ordinary people are allowing it to happen out of ignorance of that history.

Looking back at the many different photographic projects I’ve pursued, it’s becoming clear that Rescuers is the most important in terms of what the world needs to know and understand. When the New York Times Lens blog featured Rescuers in July 2018, we received emails from producers in LA asking to do a theater piece based on the book. The producers said that these stories are important as an example of our troubled world today. This is bringing a resurgence of this work and that pleases me a LOT!

JTD: Switching gears, I want to ask you about the career side of things. I am grateful that I came of age as an artist in a time when there was more support for women and LGBTQ folks in photography, but I realize this was very recently not the case (and I also think we still have a ways to go yet). What was your experience making work and seeking exhibitions in a less diverse photography and art world? Do you feel that discrimination affected your career in any way ?

GB: My career has been a wonderful addition to my life. My work has MADE me the person I’ve become – along with 20+ years of psychoanalysis, 4 relationships (now with a fabulous woman, Billie Parker – we married in 2014 because we could) 2 children, and 5 grandchildren, one of whom we lost tragically, 10 years ago. But the least important part of my career has been the exhibits. They’ve been gratifying, of course, and fun, but as I was dressing to go to the MoMA opening I thought and said to Malka, “This is really great, but it’s not going to change my life.” Probably the fact that I never had to earn money is a factor in this. Sometimes I’ve thought that this fact limited my career – if I’d needed to do commercial work I would have learned more, experienced more. And if I needed to sell my pictures, I’d have fought harder to get galleries to represent me. But I didn’t. Most of my shows have been in museums and public institutions. Howard Greenberg showed my Miami work in 2015 and he sold a lot of pictures. That was FUN! And then the History Museum Miami gathered all of us who had worked on South Beach in its heyday for a show in 2017-18. I LOVED that. My work was headlined: they used one of the images on the building like a fresco – I have no idea how they did it! – blown up to about 20’ x 16’. I’m VERY pleased you wanted to give me space in the Strange Fire Collective. I hope others have benefitted by reading this.

I continue to look at my past work to decide what exactly I want to do next. Just recently I found something that changed an entire project that I’d done in 1985. I had been commissioned to photograph grocery store employees at the 150-store family-owned H-E-B stores in Texas – they now have 300 stores. I photographed the employees in the stores and then, asking what they liked to do after work or on weekends, I went wherever they led me to take their pictures again. I call this “Labor and Leisure.” When I did the original work, I had written notes about them each evening when I was back in my motel room, on the back of the releases they’d signed. Finding these notes reminded me of how much I loved these people, how different their lives were from my life and how fascinated I was with the stories they told me. Coincidentally, it was the ONLY time I hadn’t recorded interviews with my subjects, but these notes were so good that I was moved to write the stories and reprint the whole series. I LOVE them! I tried to find these people again but there was no way, after 33 years, so I’m considering doing the same thing in New Mexico grocery stores – everyone encounters grocery employees so they’re the perfect subjects. I’m sure their stories will be very different. What’s much more difficult, however, is getting permission to photograph people these days. I’m working on it but it may not happen.

You ask if I felt discrimination and I assume you mean being a woman. I don’t think so. Perhaps by being too independent. When I got an NEA grant in 1978, another Houston photographer said he thought it was wrong because I didn’t need the money but, I told him, I needed the approval. I needed to know someone wanted me to keep photographing. I never applied for a grant again.

JTD: As someone who has had a long career in photography, what advice would you give to younger artists at the beginning of their journeys?

GB: I was lucky to have some wonderful teachers. Geoff Winningham at Rice University was a great example of the passionate photographer, and Garry Winogrand for a semester was amazing fun and full of personal wisdom. Anne Tucker taught me photo history and has been my friend from whom I’ve been absorbing lots of knowledge since we met 1975. Just reading her 40+ books was a huge addition to my life in photography. I taught photography for 2 years in the 70s at the University of Houston and I loved it, but I never really wanted to teach more. The advice I’d give to younger artists beginning their journey in photography is the advice given to me by all these inspiring teachers: pursue what you need to see in a photograph, whatever you need to understand, to know deeply. Follow your own path with curiosity and passion, and photography will reward you.