Q&A: didier william

By Rafael Soldi | December 13, 2018

Didier William is originally from Port-au-prince Haiti. He received his BFA in painting from The Maryland Institute College of Art and an MFA in painting and printmaking from Yale University School of Art. His work has been exhibited at the Bronx Museum of Art, The Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach, The Museum at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, The Fraenkel Gallery, Frederick and Freiser Gallery, and Gallery Schuster in Berlin. His work has received critical acclaim many publications including The LA times, the New York Times, Art In America, HyperAllergic, Art Critical and New York Magazine. He was an artist in residence at the Marie Walsh Sharpe Art Foundation in Brooklyn, NY and has taught at Yale School of Art, Vassar College, Columbia University, and SUNY Purchase. He is currently Associate Professor of Art and the Chair of the MFA Program at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia.

Rafael Soldi: Hi Didier, thanks for chatting with us.

Didier William: Absolutely, thanks so much for having me.

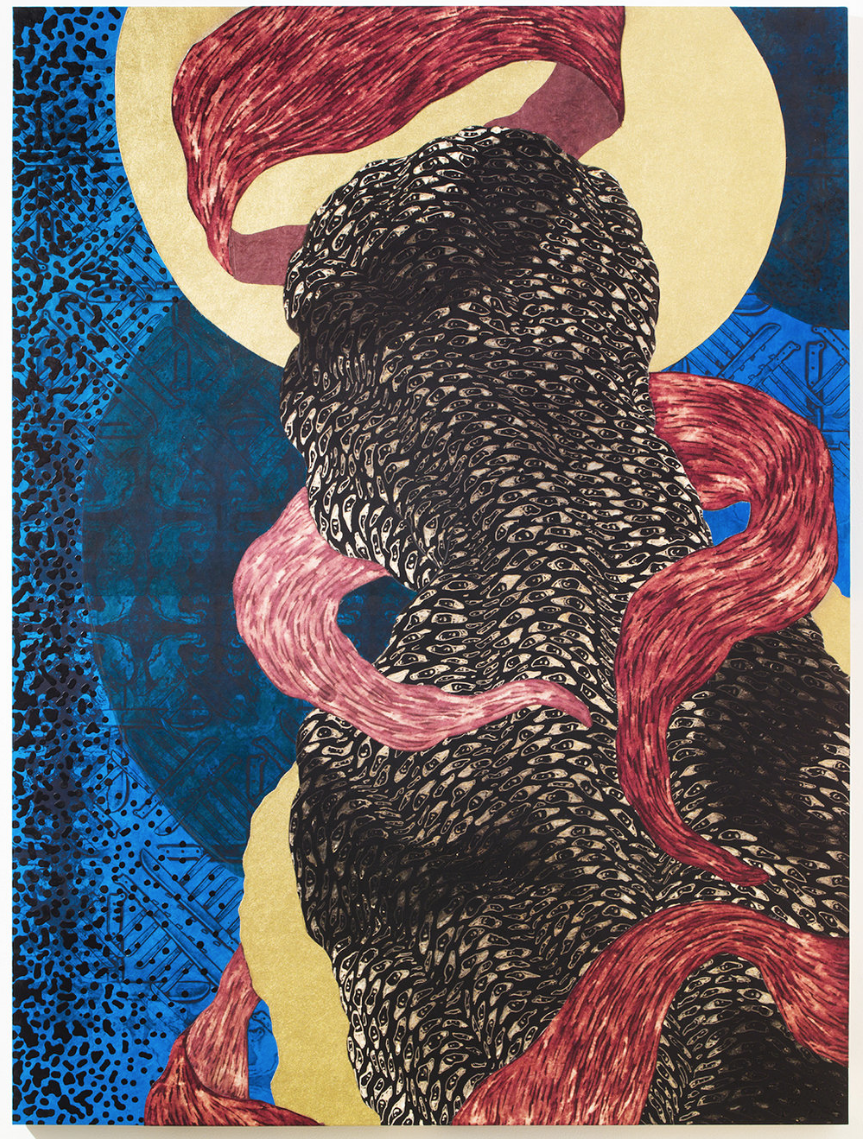

“Lage rido a, m pa vle yo we m” (2018)

RS: The bodies in your paintings are primal, unconventional, queered. Why not simply paint a conventional figure?

DW: There’s a kind of legibility that comes along with more conventional methods of figuration that I’m less interested in. I’m much more compelled by a body that’s tougher to consume. Therein lies a certain amount of agency that must remain with the body. This is especially critical when we’re talking about the histories and bodies of black and brown people. Particularly since my paintings are drawn from family oratory, historical narratives as well as mythic and ritual traditions that make up Haitian Vodou, it’s important to me to not only image a kind of queer representation, but to also deal with the curious and often nefarious gaze that precedes that representation.

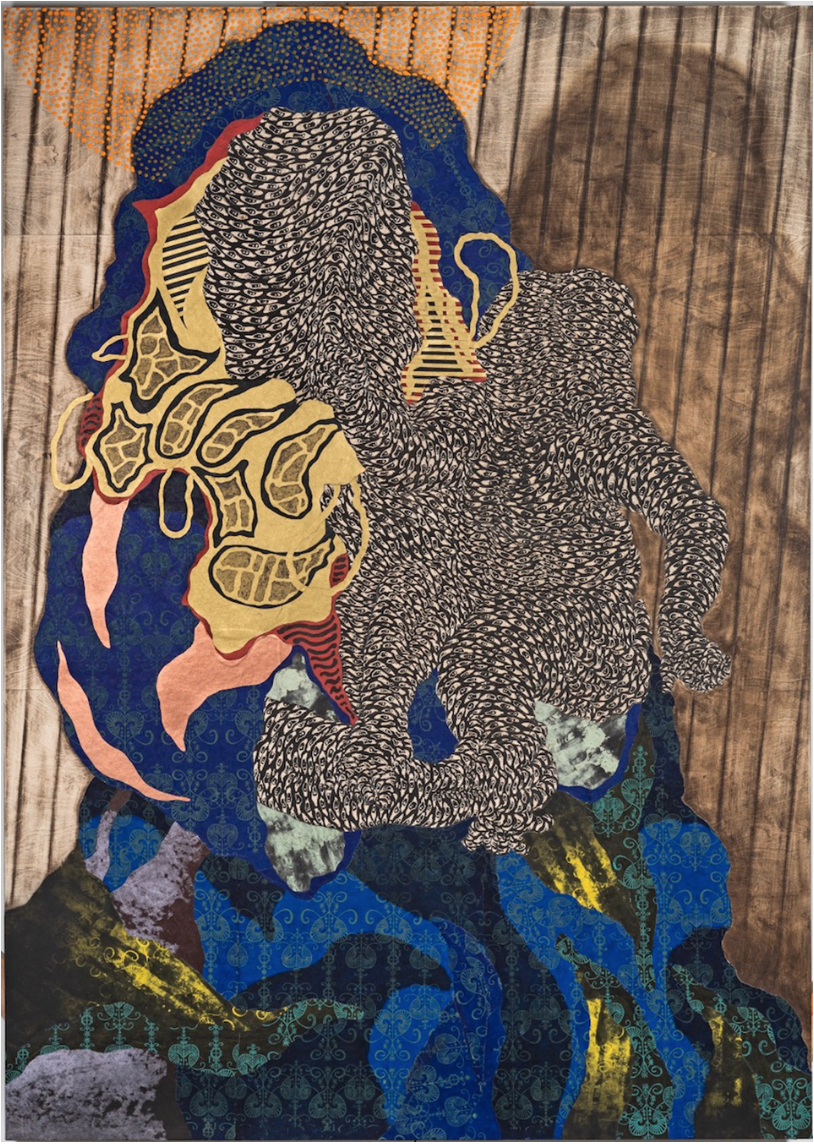

RS: Your most recent body of work, “Curtains, Stages, and Shadows,” presents bodies on platforms and stages, often masked by curtains, emerging or just off the frame, noted by a shadow. I see the stage as a very charged arena: a place where we champion and celebrate people, but when occupied by a Black body it seems remiss to ignore the recent past of slave trade auctions, or even the exploitation of Black music and culture for the enjoyment of the White Establishment. What role does the stage play in your work?

DW: The tradition of white spectatorship that you reference is certainly on my mind but not central to the narrative formations in my work. The stage in my current body of work functions like a facsimile for architecture. It evidences a kind of imaginary space that forces and maybe even requires submission to its artificial logic. Additionally, when seen together with the various stages in different paintings operating on different planes and alternating scales, the paintings engineer a tertiary space that hopefully exists outside of rational logic. For me this space is unbound by rigid binaries or cultural signifiers.

His life depends on spotted lies (2015)

RS: You’ve cited the murder of Trayvon Martin as the impetus for the figure re-entering your work. Tell us more about this.

DW: After a period of non-representational painting I was working on a new painting entitled “His life depends on spotted lies.” It’s a small portrait with a green patterned background. This was the first painting in which I carved the surface. It was also the beginning of my use of the eye motif as a materialization of the gaze. It was while I was working on this painting that George Zimmerman was acquitted of the murder of Trayvon Martin. George Zimmerman’s nefarious curiosity about Trayvon led to Trayvon losing his life. Zimmerman’s attempt to consume, contain, and police Trayvon’s body led to Trayvon losing his life. I wondered about what kind of cloak of armor would Trayvon have needed to protect himself from Zimmerman’s gaze- what would he have needed to not only refute but to return some of that gaze back onto Zimmerman himself. The gaze as a fragile but potent circuitry that exists between the viewer and its object, and how that complex system can construct and destroy the body, became a central concern for me after this painting.

“Kanpe sou janm mwen pou ou ka rive” (2018)

RS: As someone who immigrated to the United States at a young age myself, I understand the urge to address a relationship with the place we come from—finding a voice to make this work can be difficult. How do you create work about a place that has defined you but which you don’t occupy?

DW: To begin with, my work isn’t about Haiti. To say so would be to take part in the violent reduction of the complex lives of black and brown people. My work is about living in diaspora and the process of constructing meaning out of history, mythology and lived experience. Also, we must be careful not to essentialize all immigration stories. In the West, many of us occupy various diasporas and for similarly complex reasons. However, the politics of movement and migration are a bit different when we consider immigrants from countries like mine (Haiti,) where there is a long history of violent intervention from the west that has directly contributed to political, social, and economic instability.

RS: Has your work helped you better (or differently) understand your relationship to Haiti?

DW: That’s a tough question. I don’t think it has, but that’s also not really the point of the work. My work has required a tremendous amount of research and that research has helped me understand my relationship to Haiti for sure. But the purpose and focus of my practice includes many other things, some of which aren’t directly related to Haiti at all.

M'ap manje kochon sa a (2017)

RS: Academia has been a significant part of your life. How does it—if at all—influence or coexist with your art practice?

DW: Academia has been just as much a part of my identity as being an artist in the studio has been. Academia requires a persistent curiosity that I find nourishing and rewarding. Also, I tend to be a pretty orderly person and the academic calendar creates a good framework in which to organize productivity and research.

Rara (2017)

RS: Where are you looking to for visual reference in your work?

DW: I look everywhere, really. On a personal level I look at the ephemera I grew up with and by that I mean blankets, clothing, sheets, wall paper, the carpets in my parents house, the south Florida landscape, the architecture of my childhood home, etc. Perhaps less personally many of the other visual references in my work come from specific historical moments in the histories of Haiti and the United States and some art historical references as well. I also often return to the works of Robert Colescott, Belkis Ayon, and Helen Frankenthaler.

She said my braids were too tight (2013)

RS: Thanks Didier. What’s next for you?

DW: My next large scale project will likely be in 2020. For that show, I plan to dig deeper into some of the historical content which was excavated in “Curtains, Stages, and Shadows.”

All images © Didier William